鎮江市初級中學心肺復蘇知識教育現狀調查

紀學穎,陳志剛,章 衡,吳 敏,盛家鵬,姚 靜,姜皓冰

鎮江市初級中學心肺復蘇知識教育現狀調查

紀學穎1,陳志剛1,章 衡1,吳 敏2,盛家鵬3,姚 靜1,姜皓冰1

目的調查鎮江市初中生心肺復蘇(cardiopulmonary resuscitation,CPR)知識培訓的現狀,為初中生相關急救技能培訓提供參考。方法采用電話問卷調查法,首先通過電子郵件聯系鎮江市4個區及3個周邊轄市區所有學校,隨后對熟悉學校培訓實踐的工作人員進行電話采訪。登記匿名問卷的調查數據,并納入電子表格進行統計,結果采用描述性統計方法總結。結果共有35所學校完成調查,涵蓋鎮江及轄市區,共涉及中學生約14 000人。在所有學生中,最早接觸CPR培訓的是在七年級(約11歲)。尚無一所學校為學生提供規范的普及培訓計劃,但有3所(8.6%)學校由個別班級自己組織培訓,1所(2.8%)學校曾經將培訓作為課外活動的一部分。缺乏規范的CPR培訓計劃最常見原因是需要額外的上課時間,且無資金支撐(28.6%)。1所(2.8%)學校已經安裝自動體外除顫器(automated external defibrillator,AED),17所(48.6%)學校愿意無條件安裝AED,1所(2.8%)學校認為沒必要安裝,其他16所(45.8%)學校表示如果有要求會考慮安裝。過去10年間有5名學生發生心臟驟停(cardiac arrest,CA)。結論鎮江市中學的CPR培訓率較低,大多數學校在需要時無法立即獲得AED。建議鎮江教育主管部門安排上課時間并提供資金支持,以增加對初中生CPR的培訓力度。

初級中學;心肺復蘇;自動體外除顫器

院外心臟驟停(out-of-hospital cardiac arrest,OHCA)是目前全世界面臨的主要公共衛生問題之一,在美國每年約有420 000人,歐洲每年有275 000 人發生心臟驟停(cardiac arrest,CA),給醫療衛生系統造成巨大壓力[1-3]。開展基本生命支持(basic life support,BLS)培訓可改善CA患者的結局[4]。BLS中的旁觀者心肺復蘇(cardiopulmonary resuscitation,CPR)率因地點的不同而存在明顯差距,通常認為這是由于CPR知識的培訓不足或培訓知識未有效執行的結果[5]。目前,推廣“第一反應人”急救技能的培訓工作在全國范圍內已形成共識[6],其中包括在中學開設CPR等急救技能培訓課程。為了解鎮江市初中生CPR知識培訓的現狀,并為今后的培訓工作提供參考意見,筆者開展了該調查,現報道如下。

1 資料與方法

1.1 資料 2016-12,依據相關部門提供的名單對鎮江市4個區及3個周邊轄市區的所有初級中學按照設定的方法進行調查并完成資料收集工作。

1.2 調查方法 調查分兩個階段。第一階段:電子郵件咨詢。最初通過電子郵件聯系所有學校,如果愿意接受調查則在回復郵件中提供熟悉本校培訓實踐工作的相關負責人聯系電話。第二階段:電話采訪。依據已擬定的調查表,電話采訪各學校培訓相關負責人,首先說明采訪目的并解釋針對采訪內容所提出的疑問,如自動體外除顫器(automated external defibrillator,AED)的作用、意義和簡單使用方法等。所有數據以匿名方式登記在標準化的電子表格數據庫中。

1.3 調查內容 共包括19個問題,項目包括學校的基本情況(如學生人數、年齡范圍等)、急救課程設置等。其中,急救課程設置中的內容主要是學校向所有學生提供普及CPR知識培訓現狀的相關問題。其次包括AED在學校中的安放情況,以及實施學生普及訓練計劃可能遇到的障礙。此外,還統計此調查活動開展前10年間在校園內死亡的學生人數。

1.4 統計學處理 利用EXCEL 2010軟件對數據進行分析處理,結果采用頻數和率的形式表示,對所有統計數據進行描述性統計分析。

2 結 果

2.1 一般情況 調查在鎮江市4個區及3個周邊轄市區完成,在第一階段,電子郵件共聯系了59所學校,有6所學校拒絕參加(10.2%),另有40所(67.8%)學校的代表成功聯系,其中35所(59.3%)學校完成了調查。第二階段的電話采訪通常在10 min內完成,共涉及學生約14 000名,年齡11~17歲。所有學生中,最早接觸CPR知識培訓的是在七年級,約11歲。

2.2 課程設置情況 35所學校中,尚無一所學校為學生提供規范的普及培訓計劃,見表1。

表1 鎮江市接受調查35所初中CPR培訓課程設置情況

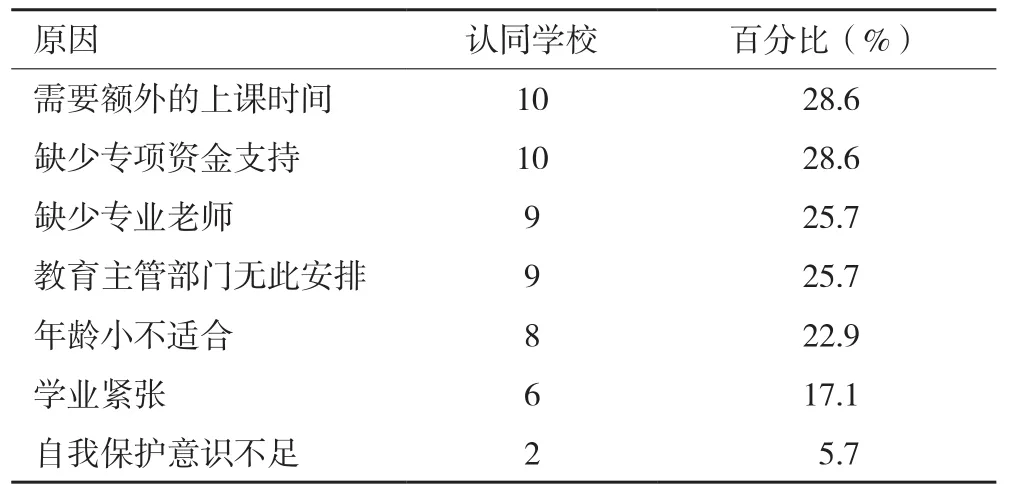

其中,未規范地普及CPR培訓計劃最常見原因是需要額外的上課時間(28.6%),且缺乏資金支撐(表2)。在過去10年間,總共有5名學生死于CA,但具體原因不明。

表2 鎮江市接受調查35所初中未規范普及CPR培訓原因

2.3 學校安裝AED情況 相關負責人采訪的反饋數據顯示1所(2.8%)學校已安裝了AED,17所(48.6%)學校愿意無條件安裝AED,1所(2.8%)學校認為沒必要安裝,其他16所(45.8%)學校表示如果有要求可以考慮安裝。

2.4 其他情況 35所接受調查的學校中有部分教師曾參加過當地紅十字會組織的急救技能培訓,并獲得初級救生員證。共有8~13個班級的學生接受過CPR培訓,主要培訓方式是觀看相關視頻或PPT后用模擬人練習,但練習時間一般小于2 min(5個周期)。接受培訓的班級在3個學年中一般只安排一次。有34所學校代表不知道美國心臟協會(American Heart Association,AHA)的BLS培訓和心臟救護(Heart Saver,HS)培訓等。尚無一所學校教師取得AHA的HS證書等。

3 討 論

目前,已證實在完整的OHCA患者生存鏈中強化其初始環節的重要性,即通過大規模教育培訓,實現早期識別心跳呼吸驟停和早期啟動旁觀者CPR[7,8]。以往的研究也表明,在OHCA患者的生存措施中,BLS措施可能比高級生命支持更重要[9],且最近的研究證據對這一觀點提供了進一步支持[10]。為提高早期旁觀者CPR和早期除顫的速度,國際復蘇聯合會(International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation,ILCOR)建議將CPR培訓和熟悉AED作為中學課程的一部分[11]。在美國多個州,接受CPR培訓已成為中學生的畢業要求[12];加拿大安大略政府已強制要求學生學習CPR以獲得中學文憑,Hart等[13]報道加拿大多倫多51.0%的中學為學生提供CPR訓練;在英國也有多所中學將CPR培訓納入到常規課程中[14]。世界衛生組織已批準了歐洲復蘇委員會(European Resuscitation Council,ERC)的“兒童拯救生命”聲明,以進一步完善學生的CPR培訓[15,16]。

本研究從鎮江初級中學的調查結果看,目前尚無一所學校在初中生中開設常規CPR課程,僅有4所受訪學校為學生提供某種形式的CPR知識培訓,且存在培訓時間短,間隔期長等不足。另外,學校的大多數員工CPR技能儲備受限。盡管目前對中學在校生實施CPR教學是否會改善CA患者的結局還無法得到準確答案,但強制所有在校學生接受該培訓,可大幅提高群眾的CPR技能,從而可能增加復蘇成功率[15,17]。針對我國尚未要求將CPR培訓作為學校的必修課程這一現狀,僅以需要額外的上課時間和缺乏資金支持等原因來解釋是不夠的。筆者認為,國家應當學習歐美國家的做法,在初中必須開設CPR課程,同時將取得相應證書(如HS的CPR+AED證書)作為初中生畢業的條件之一。對于訓練方法和學時等方面不同意見[18-20],可針對初中生的生理特點和學校的系統特點,結合社會現實,逐步摸索適合我國國情的培訓方案和計劃。

2014年,英國教育部發布一份公開聲明,建議在所有英國中小學放置AED[21]。目前研究顯示在校生CA發生率為0.04/5年,ERC指南支持將AED放置在每5年一次CA的公共區域[22]。鎮江市在過去10年里,初中校園內突然發生CA的人數較少(5人),且分散在幾所學校,這可能是學校未主動在校園安裝AED的重要原因之一。如果在鎮江每所中學都放置AED將高于ERC建議的成本效益閾值,如何控制在可接受的成本范圍內,并同時進一步提高學生對AED的認識和公眾意識尚有待研究。由于財政需求被認為是無CPR培訓計劃的最常見原因之一,建議政府能提供額外財政支持以幫助提高校園公共訪問AED的數量。

本研究中,有一些學校拒絕參與或因無法聯系到相關人員,使得最終調查數據可能存在一定偏倚。對于拒絕參加的理由尚不得而知,可能是由于本研究設計不夠嚴謹導致,提示筆者在今后的研究中對研究方法加以優化,爭取最大限度的適應性。另外,對校園內突發CA學生的數量可能存在回憶偏差,以及用于調查的工具未在單獨的群體中驗證。

總之,在鎮江市初級中學開設CPR培訓課程,并安裝AED等還有待地方政府的重視,教育主管部門需安排課時并提供資金支持,為不同年齡學生合理地調整課程。另外,對于接受CPR培訓學生的整體學習率和學習效果還有待進一步評估。

[1]Berdowski J, Berg R A, Tijssen J G P, et al. Global incidences of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and survival rates: systematic review of 67 prospective studies [J]. Resuscitation, 2010, 81(11): 1479-1487. DOI: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.08.006.

[2]Go A S, Mozaffarian D, Roger V L, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2014 update [J]. Circulation, 2014, 129(3):e18-e209. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.005746.

[3]Atwood C, Eisenberg M S, Herlitz J, et al. Incidence of EMS-treated out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in Europe [J].Resuscitation, 2005, 67(1): 75-80. DOI: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2005.03.021.

[4]Stiell I G, Wells G A, DeMaio V J, et al. Modifiable factors associated with improved cardiac arrest survival in a multicenter basic life support/defibrillation system: OPALS study phase I results [J]. Ann Emerg Med, 1999, 33(1): 44-50.

[5]Nichol G, Thomas E, Callaway C W, et al. Regional variation in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest incidence and outcome[J]. JAMA, 2008, 300(12): 1423-1431. DOI: 10.1001/jama.300.12.1423.

[6]韓自華, 田紀安, 喬 毅,等.銀川地區中學生急救知識技能培訓效果評估及培訓模式探討[J]. 中國兒童保健雜志, 2015, 23(8): 891-894. DOI: 10.11852/zgetbjzz2015-23-08-36.

[7]Lund-Kordahl I, Olasveengen T M, Lorem T, et al. Improving outcome after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest by strengthening weak links of the local Chain of Survival; quality of advanced life support and post-resuscitation care [J]. Resuscitation, 2010,81(4): 422-426. DOI: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.12.020.[8]Wissenberg M, Lippert F K, Folke F, et al. Association of national initiatives to improve cardiac arrest management with rates of bystander intervention and patient survival after outof-hospital cardiac arrest [J]. JAMA, 2013, 310(13): 1377-1384. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2013.278483.

[9]Sanghavi P, Jena A B, Newhouse J P, et al. Outcomes after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest treated by basic vs advanced life support [J]. JAMA Intern Med, 2015, 175(2): 196-204.DOI: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5420.

[10]Hasselqvist-Ax I, Riva G, Herlitz J, et al. Early cardiopulmonary resuscitation in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest [J]. N Engl J Med,2015, 372(24): 2307-2315. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1405796.

[11]Cave D M, Aufderheide T P, Beeson J, et al. Importanceand implementation of training in cardiopulmonary resuscitation and automated external defibrillation in schools a science advisory from the American Heart Association[J]. Circulation, 2011, 123(6): 691-706. DOI: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31820b5328.

[12]CPR in Schools Legislation Map [EB/OL]. [2017-01-13]. http://cpr.heart.org/AHAECC/CPRAndECC/Programs/CPRInSchools/UCM_475820_CPR-in-Schools-Legislation-Map.jsp.

[13]Hart D, Flores-Medrano O, Brooks S, et al. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation and automatic external defibrillator training in schools:“Is anyone learning how to save a life?”[J]. CJEM,2013, 15(5): 270-278.

[14]Lockey A S, Barton K, Yoxall H. Opportunities and barriers to cardiopulmonary resuscitation training in English secondary schools [J]. Eur J Emerg Med, 2015, 23(5): 381-385. DOI:10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000307.

[15]B?ttiger B W, Van Aken H. Kids save lives–Training school children in cardiopulmonary resuscitation worldwide is now endorsed by the World Health Organization (WHO)[J]. Resuscitation, 2015, 94: A5-A7. DOI: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.07.005.

[16]Bohn A, Lukas R P, Breckwoldt J, et al.‘Kids save lives’: why schoolchildren should train in cardiopulmonary resuscitation [J]. Curr Opin Crit Care, 2015, 21(3): 220-225. DOI: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000204.

[17]Greif R, Lockey A S, Conaghan P, et al. European resuscitation council guidelines for resuscitation 2015: section 10. Education and implementation of resuscitation [J]. Resuscitation, 2015,95: 288-301. DOI: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.07.032.

[18]B?ttiger B W, Bossaert L L, Castrén M, et al. Kids Save Lives-ERC position statement on school children education in CPR:" Hands that help-Training children is training for life" [J]. Resuscitation, 2016, 105: A1-A3. DOI: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2016.06.005.

[19]J?ntti H, Silfvast T, Turpeinen A, et al. Nationwide survey of resuscitation education in Finland [J]. Resuscitation, 2009, 80(9): 1043-1046. DOI: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.05.027.

[20]Miró ò, Jiménez-Fábrega X, Espigol G, et al. Teaching basic life support to 12-16 year olds in Barcelona schools: views of head teachers [J]. Resuscitation, 2006, 70(1): 107-116.DOI: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2005.11.015.

[21]UK Department of Education. Health and Safety in Schools.Automated external defibrillators (AEDs) in schools [EB/OL].[2017-01-13]. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/automated-external-defibrillators-aeds-in-schools.

[22]Perkins G D, Handley A J, Koster R W, et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2015:Section 2. Adult basic life support and automated external defibrillation [J]. Resuscitation , 2015, 95: 81-99. DOI:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.07.015.

(2017-05-08收稿 2017-07-10修回)

(本文編輯 付 輝)

Investigation of the status quo of cardiopulmonary resuscitation education in junior middle schools in Zhenjiang city

JI Xueying1, CHEN Zhigang1, ZHANG Heng1, WU Min2, SHENG Jiapeng3, YAO Jing1, and JIANG Haobing1. 1. Department of Training, 2.Department of Dispatch, 3. Hospital Administration Office, Emergency Medical Center of Zhenjiang, Zhenjiang 212003, China

ObjectiveThe objective of this study was to investigate the status quo of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR)training in junior middle schools in Zhenjiang city, and to provide reference for relevant emergency skills training for junior school students.MethodsAll junior middle schools in 4 districts of Zhenjiang city and 3 peripheral administrative regions were contacted by e-mail informing them of the study and inviting their participation; thereafter telephonic interviews were conducted with staff members who are familiar with the school's CPR training practice. The survey data were registered and included in the spreadsheet to analyze, and the results were summarized using descriptive statistics methods.ResultsA total of 35 schools involving approximately 14,000 students participated in the survey, covering Zhenjiang and its administrative areas. Of all students, the earliest to exposure CPR training was in grade seven(approximately 11 years old). None of the schools provided a standardized training program for students, while 3 schools (8.6%) provided training organized by individual classes, and 1 (2.8%) provided training as part of their extracurricular activities. The most common reasons for the lack of a standardized CPR training program was due to the requirement of extra class time and the absence of financial support(28.6%). One school (2.8%) had installed automated external defibrillator (AED), 17 schools (48.6%) were willing to install an AED and one school (2.8%) didn't see a need to install, and the remaining 16 schools (45.8%) indicated they would consider installation if required to do so. Over the past 10 years, 5 students had a cardiac arrest (CA).ConclusionsThe CPR training rate in junior middle schools in Zhenjiang city is still low and most schools do not have AED on site in case of emergency. It is suggested that the education authorities in Zhenjiang city schedule class time and provide financial support to strengthen the CPR training for junior school students .

junior middle schools; cardiopulmonary resuscitation; automated external defibrillator

R193

Corresponding author: CHEN Zhigang, E-mail: cxc_2002@139.com

10.13919/j.issn.2095-6274.2017.09.004

212003,江蘇省鎮江市急救中心: 1. 培訓科,2. 調度科,3. 辦公室

陳志剛,E-mail:cxc_2002@139.com