接納承諾療法的作用機制——基于元分析結構方程模型*

任志洪 趙春曉 卞 誠 朱文臻 江光榮 祝卓宏

?

接納承諾療法的作用機制——基于元分析結構方程模型

任志洪趙春曉卞 誠朱文臻江光榮祝卓宏

(青少年網絡心理與行為教育部重點實驗室, 華中師范大學心理學院, 湖北省人的發展與心理健康重點實驗室, 武漢 430079) (北京師范大學認知神經科學與學習國家重點實驗室, IDG/麥戈文腦科學研究院, 北京, 100875) (北德克薩斯大學, 德克薩斯, 76203, 美國) (中國科學院心理研究所, 中國科學院心理研究所心理健康重點實驗室, 北京 100101)

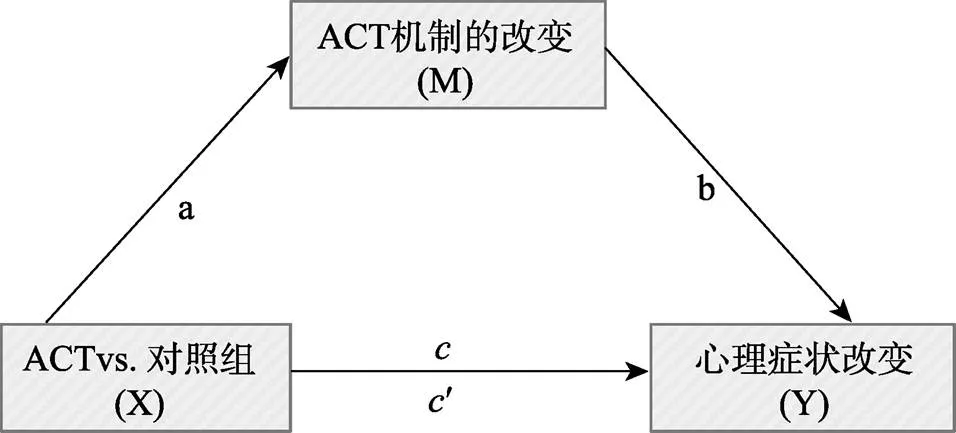

接納承諾療法(Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, ACT)被認為是行為治療“第三浪潮”的重要代表。本研究使用元分析結構方程模型, 考察ACT的作用機制。通過數據庫檢索與篩選, 最終納入文獻50篇。結果發現: ACT所假設的心理靈活性、接納、此時此刻、價值的中介作用都達到統計顯著, 認知解離這一中介變量并不顯著; 中介機制在網絡化干預中仍然得到檢驗; 相較之傳統CBT, ACT在所假設的機制上有其區別于CBT的優勢。后續臨床研究應更全面地測量6大核心機制, 關注對美好生活提升的影響, 采用多點瞬時評價法, 并盡可能使用更高級、更先進的統計方法檢驗其作用機制。

接納承諾療法; 元分析結構方程模型; 作用機制; 中介檢驗; 認知行為療法

1 引言

近年來, 新興的行為治療“第三浪潮”備受關注。行為治療被喻為“第一浪潮”, 它基于條件反射和新行為原則, 直接關注有問題的行為和情緒; “第二浪潮”則強調對非理性思維、病理性認知圖式或錯誤的信息處理方式進行矯正, 進而減輕或消除癥狀, 這種以認知改變為重心的治療被稱為“認知行為療法” (Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, CBT) (Beck, 1993)。“第三浪潮”則對心理現象的語境和功能更為敏感, 而不僅僅關注其形式(Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda, & Lillis, 2006), 典型的療法包括接納與承諾療法(Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, ACT)、辯證行為療法(Dialectical Behavioral Therapy, DBT)、正念認知療法(Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy, MBCT)、慈悲聚焦療法(Compassion Focused Therapy, CFT)等(Hacker, Stone, & MacBeth, 2016)。

盡管研究者們對哪些療法屬于“第三浪潮”仍存在爭議, 但為了促進療法的共同發展, 共識多于分歧。Hayes, Villatte, Levin和Hildebrandt (2011)對“第三浪潮”進行了修正, 用“基于語境的認知行為治療” (Contextual Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, CCBT)作統稱, 將關注點從原來的哪些治療方法應該被納入“第三浪潮”, 轉為強調新興療法在理論、治療過程和程序上“開放, 主動和覺察”的特點。在這些基于語境的認知行為治療中, ACT最受關注, 近年來被引用的頻次最多(Dimidjian et al., 2016)。本研究的目的在于系統考察ACT的作用機制, 相較之傳統CBT的特異性, 以及在網絡環境中的可遷移性。

1.1 ACT的療效

探索ACT治療的作用機制之前, 需要先考察其有效性。在循證心理治療中, 隨機對照試驗(Randomized Controlled Trial, RCT)設計被作為療法評估的“黃金標準”, 元分析證據被當作證據效度的最高標準(Wampold & Imel, 2015)。通常, 療效有絕對療效和相對療效之分, 絕對療效旨在檢驗該療法是否有效, 其對照組一般是等待組(Waiting List, WL)、常規治療(Treatment as Usual, TAU)、安慰劑治療等; 相對療效用于檢驗該療法是否比其他療法更為有效, 其對照組通常是高度結構化已確立的療法, 比如傳統CBT、認知療法(Cognitive Therapy, CT)、人本主義療法等(Wampold, 2013)。那么, ACT的療效如何呢?

一方面, 從絕對療效角度, 元分析的結果支持ACT具有中到大的效果量。最早的元分析納入9篇RCT, 對照組包括WL、TAU、心理安慰劑組, 結果發現, ACT后測具有中等效果量(= 0.66) (Hayes, et al., 2006); 最近一項納入60項RCT研究的元分析(?st, 2014)包括了更為廣泛的心理、身體和工作壓力相關問題, 相較之WL (= 0.63)、TAU (= 0.55)和心理安慰劑組(= 0.59), 其后測的絕對療效都具有中到大的效果量。

另一方面, 從相對療效角度, 與高度結構化已確立的療法對比, ACT的效果量大小不一。最早的元分析發現(Hayes et al., 2006)相較之傳統CBT和CT, ACT具有中到大的效果量(= 0.73), 但該研究只納入了4項RCT研究。隨后, Ruiz (2012)的元分析納入16項RCT研究, 包括成癮、慢性疼痛、焦慮癥、抑郁癥、壓力以及癌癥的心理體驗等, 結果發現與傳統CBT相比, ACT的后測(= 0.37;= 0.42)和追蹤效果量都為小到中等, 之后更大樣本的RCT研究(?st, 2014)發現其后測效果量較小(= 60,= 0.16)。最近, 一項納入39項RCT研究的元分析也得到類似的結果, 這項研究將治療限定為臨床相關疾病, 其干預中80%的成分包含ACT (A-Tjak et al., 2015)。

綜上可見, 檢驗ACT的絕對療效的元分析表明 ACT是有效的, 那么ACT是如何有效的, 即其作用機制值得進一步探究。

1.2 心理治療機制的研究方法

機制是指解釋改變過程, 而識別中介變量是檢驗作用機制的重要一步, 它是在統計上解釋自變量與因變量關系的中間變量, 解釋治療為何和通過哪種方式作用于效果(MacKinnon, Fairchild, & Fritz, 2007)。

Kazdin (2007)歸納了識別心理治療機制或中介變量的基本標準。首先, 研究中所提出的機制/中介變量和預期結果變量有明確的關聯(強相關性準則)。其次, 結果變量和中介變量需要在多個時間點進行測量, 從而可以確定中介變量的變化先于結果變量的變化(時間優先準則)。再次, 需要操作實驗設計(增加或減少特定機制), 激活和(或)拆除特定機制來確定效應的特異性(特異性準則)。此外, 需要觀察“劑量?反應”關系, 即針對性地激活越多的機制劑量, 觀察結果是否改變越強(梯度準則)。最后, 研究結果的可重復性(一致性標準)。

具體到統計上, 確立一個中介變量需要諸多條件。在很長一段時間, 中介僅指統計上的中介, 即從統計上證明治療(X)對結果(Y)的影響可以通過第三變量(中介變量M)所解釋。中介分析的方法眾多, 顯變量檢驗通常基于線性回歸模型, 而潛變量檢驗則使用結構方程模型(Structural Equation Modeling, SEM)。雖然SEM技術相較之線性回歸更具優勢, 且研究者也更為推薦, 然而, 現今心理治療研究中的中介檢驗, 傳統線性回歸法仍然是最為流行的方法(Gu, Strauss, Bond, & Cavanagh, 2015)。其中, 檢驗中介最經典的方法是逐步檢驗法(Baron & Kenny, 1986), 根據該方法, 治療研究中介變量的確立需要滿足以下幾個條件(Lemmens, Müller, Arntz, & Huibers, 2016): (1)存在治療主效應(療效檢驗); (2)治療與中介變量的改變相關(干預檢驗); (3)中介變量的改變和結果變量的改變相關(心理病理學檢驗); (4)當在統計上加入中介變量檢驗時, 治療的效果不顯著(完全中介)或顯著性降低(部分中介)。

統計上的中介檢驗固然重要, 但鑒別治療的中介變量仍需要一些額外的實驗設計。根據較新的標準, 中介變量的鑒別需要建立在理論基礎上, 通過嚴格的RCT, 進行合理間隔的重復測量, 并且要求有足夠的統計力和合適的對照組(Kazdin, 2007; MacKinnon et al., 2007); 接著, 需要改進實驗設計, 能在治療研究中操作所提出的中介變量(Alsubaie et al., 2017); 此外, 根據治療理論對改變過程的界定, 通常評價單一的中介變量是不足夠的, 研究者推薦應該包括多個中介變量競爭假設, 檢驗替代解釋模型, 并考察理論上中介變量之間的相互作用(Lemmens et al., 2016)。

1.3 ACT的作用機制

ACT基于關系框架理論, 其治療機制模型假設是以提升心理靈活性為核心, 包括6大成分, 即, 接納(愿意接觸內心體驗)、解離(將認知體驗為持續的過程, 而非認知過度調節行為)、以已為景(把內在體驗作為自身體驗的背景, 而不把它看作是體驗本身)、此時此刻(能夠靈活地接觸發生的內部與外部事件, 不作評判)、價值(選擇持續行為模式所需的結果, 以建立強化物)、承諾行動(靈活地朝有價值的方向作出行動) (Hayes et al., 2006; 曾祥龍, 劉翔平, 于是, 2011; 張婍, 王淑娟, 祝卓宏, 2012)。上述機制假設是否能得到實證研究支持?

其一, 目前對ACT的治療機制模型的實證檢驗結果存在不一致。部分研究驗證了心理靈活性的改變在臨床結果中起中介作用(Wicksell et al., 2013); 有的研究結果并不一致, 比如無法檢驗到對疼痛的接納改變在實驗條件組與追蹤臨床結果之間起部分或完全中介作用(Luciano et al., 2014); 再有研究發現, 在社區環境, ACT六邊形模式的心理靈活性及6大核心機制的改變對焦慮障礙的改變作用是不一致的(Forman, Herbert, Moitra, Yeomans, & Geller, 2007; Hayes et al., 2006)。有元分析(Bluett, Homan, Morrison, Levin, & Twohig, 2014)考察63個檢驗焦慮與心理靈活性關系的研究, 結果顯示, 二者在臨床與非臨床樣本, 都具有中等程度的相關, 即, 在中等程度上支持心理靈活性是治療改變的中介變量的可能。但不難看出, 該元分析僅是檢驗了心理靈活性與癥狀降低之間的相關性, 并沒有直接檢驗中介作用。那么, 聚合所有相關研究進行中介檢驗, 是否能支持ACT的治療機制模型?

其二, ACT所假設的作用機制是否具有特異性?ACT療法在創始就強調其機制的獨特性。Hayes(2004)認為, 相較之“第二浪潮”的傳統CBT, 雖然“第三浪潮”與傳統CBT有相同的干預成分, 比如自我監控、暴露和反應阻止法, 但二者在理論假設和干預方法都有所區別。在理論假設上, 區別于傳統CBT, ACT基于關系參照理論和功能情境主義哲學取向。在干預方法上, 傳統CBT聚焦內容和認知過程的有效性, 而ACT側重功能或對認知和情緒的覺察(Hofmann & Asmundson, 2008)。因此, ACT重視提升接納、正念、元認知和心理靈活性, 降低經驗回避, 建立更為寬廣、靈活、有效的應對方式, 而不僅僅是針對癥狀的認知和內容進行反駁(Bond et al., 2011; Hayes et al., 2011)。那么, 綜合分析, 相較之傳統CBT, ACT所強調的機制是否確實具有特異質呢?

其三, 這種機制在網絡環境中是否能得到遷移?在影響心理治療效果的所有因素中, 當事人與咨詢師所形成的咨詢同盟被認為是最大的影響因素, 咨詢技術特征所帶來的效果量提升較小(Wampold & Imel, 2015)。隨著計算機網絡化技術的發展, 近年來心理疾病的網絡化干預受到較多研究者的關注, 網絡化的干預使咨詢同盟幾乎消失, 然而一些經典的干預方法在網絡環境中傳播, 比如網絡化CBT干預, 其作用機制仍然能得以檢驗(任志洪等, 2016)。而目前基于對ACT網絡化干預的作用機制的檢驗結果存在不一致: 比如, 一項對234名大學生群體進行心理健康的網絡化干預的研究結果發現, 相較之對照組, ACT干預的心理靈活性的提升與心理健康水平提升有較強關聯(Levin, Hayes, Pistorello, & Seeley, 2016), 針對抑郁的ACT網絡化干預也支持心理靈活性的改變與癥狀改變的相關性(Lappalainen, Langrial, Oinas-Kukkonen, Tolvanen, & Lappalainen, 2015); 但也有研究發現網絡化ACT干預相較之等待組, 盡管對抑郁和焦慮癥狀有顯著的改善, 但當事人的心理靈活性并沒有顯著改變(Levin, Pistorello, Seeley, & Hayes, 2014)。因而, 有必要系統檢驗ACT所強調的作用機制在網絡環境中是否能得到遷移。

1.4 本研究的目的

近年來, 元分析和結構方程結合所發展的元分析結構方程模型(Meta-analytic Structural Equation Model, MASEM) (Cheung, 2015), 使系統考察心理治療作用機制成為可能。相較之原始單一的RCT研究, 通過兩階段MASEM匯聚多樣本, 可以綜合樣本量, 提升模型統計力, 獲得更穩定的模型估計(Montazemi & Qahri-Saremi, 2015)。

鑒于目前對ACT的作用機制缺乏系統檢驗, 其機制是否有區別于傳統CBT的特異性, 以及在網絡化干預環境的可遷移性等問題, 還未明確。本研究主要使用MASEM考察ACT的三方面作用機制:(1)檢驗心理靈活性及6大核心機制在ACT治療中的中介作用; (2)考察相較之傳統CBT, ACT所強調的機制是否具有特異性; (3)ACT的作用機制的可遷移性, 特別是在網絡化干預中是否仍然存在。

2 研究方法

2.1 文獻檢索

在Web of Science、PsycARTICLES、PsycINFO、PubMed、Elsevier、EBSCO、Wiley online library等數據庫, 檢索已經發表的英文文獻。將檢索關鍵詞分為: 接納承諾療法(Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, ACT); 與其對應的心理機制(acceptance、cognitive defusion、self-as-context、committed action、contact with the present moment、values、psychological flexibility)進行配對組合檢索。首次文獻檢索時間2016年10月, 2017年11月二次更新。文獻由第二作者篩選, 第三作者核對, 有異議文獻與第一作者協商一致解決。詳細過程見圖1。

2.2 納入與排除標準

文獻納入與排除標準為, 納入: 1)成年人樣本(年齡 > 18歲), 2)隨機對照試驗(RCT)或是準試驗設計, 測量ACT干預前后變量的變化, 3)對心理健康(臨床或非臨床)結果前后測量改變進行定量評估, 4)對中介變量進行前后測定量評估。排除: 1)混合干預方式, 即除了ACT還包含其他干預手段, 或含有接納成分而非完整的ACT治療(Wicksell, Ahlqvist, Bring, Melin, & Olsson, 2008)或含接納的行為治療(Eustis, Hayes-Skelton, Roemer, & Orsillo, 2016; Millstein, Orsillo, Hayes-Skelton, & Roemer, 2015), 2)藥物治療對照組(Luciano et al., 2014)。

數據摘取分兩類:一類是描述研究特征的基礎數據, 我們采用第二作者摘取, 第三作者核對的形式; 另一類是真正納入統計分析的核心數據, 我們采用第二作者和第三作者分別編碼, 求得評分者一致性信度kappa系數為0.89, 根據在0.75及以上被認為一致性非常好的判別標準(Orwin, 1994), 說明本研究編碼具有較高的一致性。最后, 與第一作者協商一致后確定最終編碼。

圖1 文獻檢索和篩選流程圖

2.3 中介檢驗:兩階段結構方程元分析

中介效應檢驗采用MASEM進行分析。Cheung (2015)提出兩階段結構方程模型(Two-Stage Structural Equation Modeling, TSSEM), 采用極大似然估計, 使標準誤估計更加精確。使用R語言(Ver.3.5.2)中的metaSEM包(Ver.1.2.0)進行TSSEM分析(Cheung, 2015)。具體來說:

2.3.1 考察模型因素的測量不變性(第一階段分析)

為了減少原始研究匯聚數據, 潛在的人為因素對結構方程參數估計的影響, 根據(Montazemi & Qahri-Saremi, 2015; Schmidt & Hunter, 2015)建議, 本研究中可能有5個人為因素影響元分析檢驗理論假設, 處理方法分別如下:

(1)數據的獨立性。數據的非獨立性違反了元分析假設(Schmidt & Hunter, 2015)。因此, 我們使用以下方法, 以保證兩階段隨機效應MASEM分析數據的獨立性。當一篇研究測量了多個結果時, 我們借鑒前人的系統選擇方法(Gu et al., 2015): 優先選擇心理病理的整體測量, 其次選擇抑郁和焦慮測量結果; 同時包含他評與自評的測量結果的研究, 優先選取臨床咨詢師評價(Forman et al., 2007);同時測量了焦慮與抑郁的研究, 選擇與樣本量匹配的結果; 若是樣本量不匹配, 則根據被試基線的抑郁與焦慮水平, 選取水平更高的結果; 既沒有測量抑郁也沒有測量焦慮的研究, 選取壓力作為心理健康結果, 如果也沒有壓力則選擇消極影響; 最后, 如果一個結果變量有兩個或是多個測量工具, 則選擇有更強測量學特征的結果。相對的, 若是沒有包含心理健康結果的文獻, 不納入TSSEM分析。雖然可能在一項研究中計算多結果測量的均值, 但無法直接獲得每項研究平均相關系數的方差, 因而, 每項研究僅提取一個心理健康結果指標較為適宜。

(2)編碼過程。本研究的主要目的并非關注ACT對心理疾病治療的效果量, 而旨在著重考察其作用機制。因而, 為了使用TSSEM考察ACT的作用機制, 從每一篇文章中提取X (ACT vs. 對照組), M變量(中介變量)在干預前后的改變以及Y變量(結果變量)干預前后的改變之間的兩兩相關系數, 并且提取每項研究的樣本量。如果研究并沒有提供明確的相關系數, 則利用均值、標準差、值、值和效果量(或值)計算相關系數(Lipsey & Wilson, 2001; Morris, 2008)。

(3)評價潛在的數據缺失影響。在元分析中, 可能存在潛在的“文件抽屜問題” (file drawer problem), 即效果不顯著的論文相比效果顯著的論文, 更不易被發表, 導致出版偏差(Higgins & Thompson, 2002)。我們先使用Begg and Mazumdar rank correlation和Egger’s regression intercept評估可能的出版偏差, 若存在偏差, 進而使用失安全系數(fail-safe Number,)檢驗可能的出版偏差對效果量的影響(Rothstein, Sutton, & Borenstein, 2005)。失安全系數是指讓現有結論變得不顯著的研究個數的最小值,越大, 偏倚的可能性越小; 當小于5+ 10 (為原始研究的數目)時, 發表偏倚應引起警惕(Rothstein et al., 2005)。本研究中, 多數的值都較大(僅ACT vs. CBT的c路徑可能存在出版偏差), 整體上說, 本研究結果具有較強的穩健性。

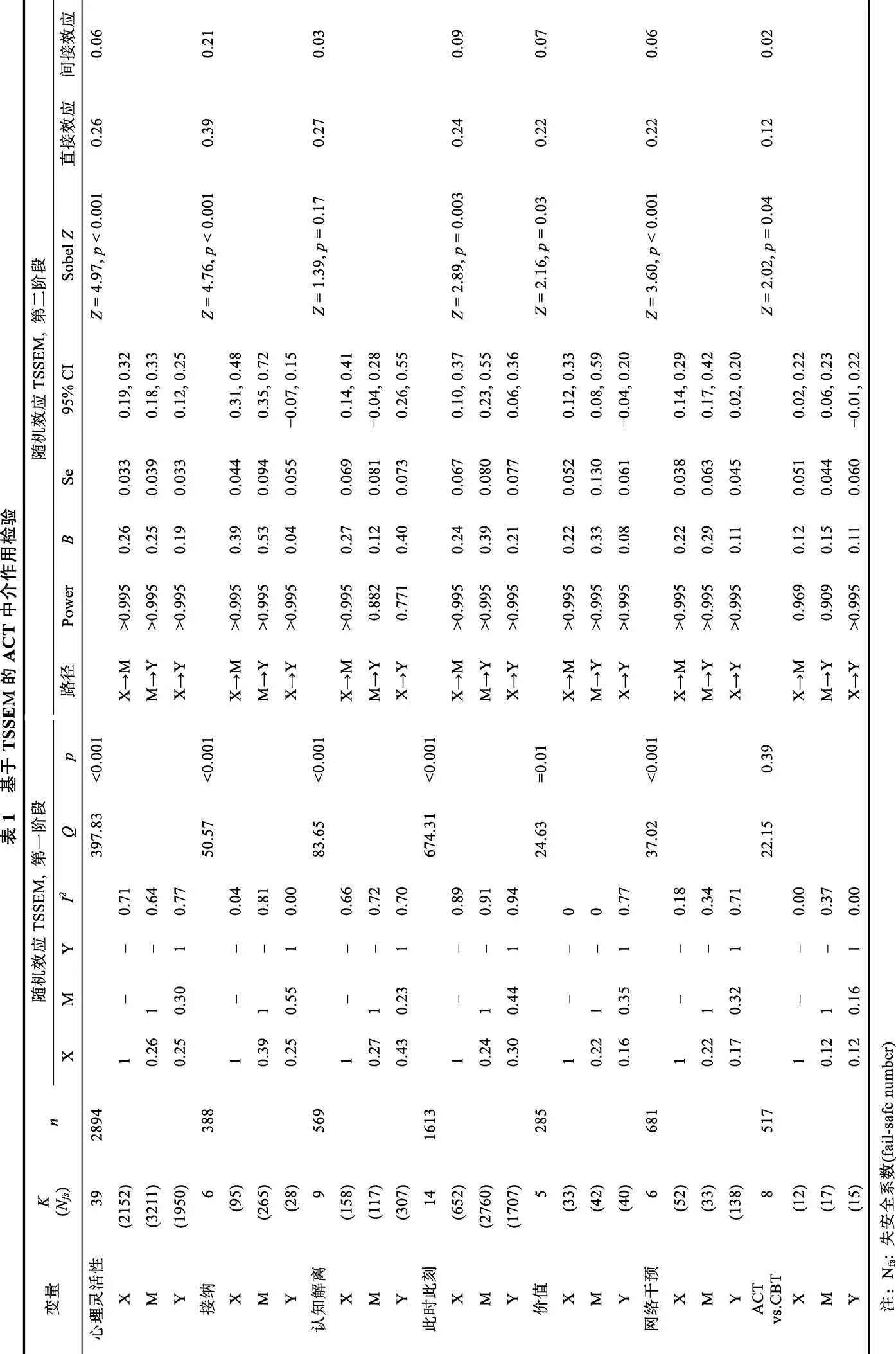

(4)檢驗Type II錯誤。統計力是統計檢驗中的一個重要成分, 即零假設事實不成立, 那么在多大程度上, 統計結果拒絕零假設。為了評價Type II錯誤的風險, 我們基于各自合并的樣本量, 根據所假設檢驗的中介變量的合并相關系數, 使用G*Power3.1計算其統計力(Faul, Erdfelder, Lang, & Buchner, 2007)。統計力分析結果顯示(表1), 除認知解離A→C的統計為0.771, 其他所有參數都大于0.8這一被廣泛接受的統計力閾值。因此, 可以確信, MASEM分析的所有模型均具有足夠的統計檢驗力以拒絕事實不成立的零假設(Cohen, 1988; Montazemi & Qahri-Saremi, 2015)。

(5) MASEM分析中原始研究異質性問題。在MASEM分析中可以使用固定效應模型(fixed-effects model)和隨機效應模型(random-effects model) (Cheung, 2014)。根據Cheung和Chan (2005)的推薦, 鑒于樣本、研究設計和效果量在不同研究間存在差異, 在MASEM分析中優先使用隨機效應模型, 如果統計結果證明效果量是同質的, 則在第二步分析中使用固定效應模型。使用值和考察模型的異質性及其大小:< 0.05, 表示研究之間是異質的;> 50%則為高異質性, 25%~50%為中等異質性, < 25%為低等異質性(Higgins & Thompson, 2002)。分析結果如表1所示。

2.3.2 評價SEM模型(第二階段分析)

根據Cheung (2015)所提示的兩階段隨機效應MASEM分析的步驟, 第二階段分析是使用元分析對原始研究進行效果量合并, 結合SEM技術進行參數估計。具體來說, 因在現實中, 并非所有原始研究中涉及的變量都是同時測量的, 因此我們使用加權矩陣, 漸近協方差矩陣(asymptotic covariance matrix), 以校正合并相關系數中的異構性和每個相關矩陣中樣本量的不同(Viswesvaran & Ones, 1995)。使用合并矩陣的非標準化回歸系數和標準誤進行Sobel檢驗, 以考察中介模型間接路徑的顯著性水平(Gu et al., 2015)。

3 結果

3.1 納入文獻基本描述

本研究最終納入元分析文獻50篇, 其中RCT研究44篇, 涉及疼痛障礙、人格障礙、抑郁、焦慮、物質濫用等多種心理問題, 甚至包括正常群體的職業倦怠等(詳見電子版附錄表1)。研究ACT的核心機制心理靈活性的文獻最多(= 39), 其次是此時此刻(= 14)、接納(= 6)、認知解離(= 9)和價值(= 5), 因以已為景(Yadavaia, Hayes, & Vilardaga, 2014)和承諾行動(Avdagic, Morrissey, & Boschen, 2014)都僅納入1篇文獻, 未進行后續的MASEM分析。雖然有14篇對ACT假設的機制進行多中介變量測量(大于1項), 但并沒有同時測量ACT六大作用機制的文獻。納入的文獻中, 相對療效主要以傳統CBT作為對照組(= 8); 有6項RCT考察了ACT基于網絡傳播的作用機制。

大多數研究測量了ACT假設的機制變量但并沒有在統計上進行中介效應檢驗(= 33), 僅有少數研究(= 16)使用推薦的Bootstrap法進行中介檢驗(Preacher & Hayes, 2008), 個別研究仍使用傳統的回歸逐步檢驗法(Kemani, Hesser, Olsson, Lekander, & Wicksell, 2016)。當然, 也有些研究采用更為復雜的中介檢驗方法, 比如多水平(HLM)中介模型(Rost, Wilson, Buchanan, Hildebrandt, & Mutch, 2012; Zarling, Lawrence, & Marchman, 2015)和結構方程模型(Eilenberg, Hoffmann, Jensen, & Frostholm, 2017)。雖然在小樣本分析上, HLM有優勢, 但應該注意到HLM是基于正常分布假設, 而Bootstrap法在非正態分布中更具優勢(Swain, Hancock, Hainsworth, & Bowman, 2015)。

實驗設計上, 較少研究考慮機制變量的時序作用, 僅有8篇進行了多點測量, 但大部分多點測量使用的是前測、后測和追蹤測量(Luciano et al., 2014; Stafford-Brown & Pakenham, 2012; Wetherell et al., 2011; Yadavaia et al., 2014), 追蹤是在治療結束后, 并非在有效治療階段; 少部分是在治療期間測量機制變量(Lloyd, Bond, & Flaxman, 2013; Westin et al., 2011), 甚至對機制在治療間進行多次測量(Rost et al., 2012), 但僅有極少部分在每次治療單元都進行機制和效果測量(Kemani et al., 2016)。

3.2 ACT作用機制檢驗

3.2.1 心理靈活性

心理靈活性作為6大ACT作用機制的統稱, 納入研究39項, 樣本量2894, 其測量主要使用接納和行動問卷(Acceptance and Action Questionnaire, AAQ; 例如, Arch et al., 2012)、接納和行動問卷II (Acceptance and Action Questionnaire – II, AAQ-II; 例如, Levin, Haeger, Pierce, & Twohig, 2017b)、疼痛心理的不靈活性量表(The Psychological Inflexibility in Pain Scale, PIPS) (Trompetter, Bohlmeijer, Veehof, & Schreurs, 2015; Wicksell et al., 2013)。在39項納入研究中, 34項RCT和5項準實驗研究, 以整體精神癥狀(Global Psychopathological Symptoms,= 16)為主要測量結果的最多, 其次是抑郁水平(= 9)。

表1呈現了39項納入研究的X, M, Y的兩兩相關合并系數, 三個相關系數都呈現高顯著性。異質性檢驗發現,值顯著(= 397.83,< 0.001), 表示39項研究的相關矩陣有較大差異, 兩兩相關的異質性I都大于50%, 顯示較大的異質性, 適用隨機效應模型。圖2呈現了TSSEM分析第二階段心理靈活性作為中介變量的模型檢驗路徑圖。雖然回歸系數(= 0.19)依然顯著, 但比原始值(= 0.25)有所下降, 為部分中介。使用X和M, M和Y的相關系數和標準誤進行Sobel檢驗, 證明心理靈活性在ACT對心理健康的結果改變上, 起到顯著的中介作用(= 4.97,< 0.001)。

3.2.2 接納

納入的研究6項, 都為RCT研究, 樣本量388, 主要測量使用慢性疼痛接納問卷(Chronic Pain Acceptance Questionnaire, CPAQ) (例如, Luciano et al., 2014)。結果測量的心理變量包括焦慮(= 3)、抑郁(= 2)和整體評價(= 1)。合并效應值的三個相關系數都具有高顯著性(見表1)且異質性顯著(= 50.57,< 0.001), 接納具有較大程度的異質性(= 0.81)。在中介的路徑模型檢驗中, ACT的對心理健康結果的改變路徑(= 0.04), 比直接路徑(= 0.25)有顯著下降, 且不再顯著, Sobel檢驗顯示, 接納在ACT與心理健康結果改變之間的中介作用顯著(= 4.76,< 0.001), 說明接納在二者的關系中起到完全中介的作用。

圖2 TSSEM分析路徑圖, 以ACT假設機制的改變為中介變量

3.2.3 認知解離

納入的研究文獻9篇(RCTs = 6, 準實驗 = 3), 樣本量569, 主要測量使用自動思維問卷(AutomaticThought Questionnaire, ATQ) (Clarke, Kingston, James, Bolderston, & Remington, 2014; Forman et al., 2012; Lappalainen et al., 2015; Waters, Frude, Flaxman, & Boyd, 2018; Zettle, Rains, & Hayes, 2011), 德雷塞爾解離問卷(Drexel Defusion Scale, DDS) (Juarascio et al., 2013), 白熊思維抑制量表(White Bear Thought Suppression Inventory, WBSI) (Lappalainen et al., 2015; Rost et al., 2012; Stafford-Brown & Pakenham, 2012)和青少年逃避與融合問卷(Avoidance and Fusion Questionnaire for Youth, AFQ-Y) (Levin et al., 2016)。在納入的9篇研究中, 主要使用整體精神癥狀(= 3)和抑郁(= 3)作為結果測量。

合并效應值的三個相關系數都具有較高顯著性(見表1), 異質性顯著(= 83.65,< 0.001)。在認知解離作為中介變量的中介模型檢驗中, 雖然X→Y階段二路徑系數(= 0.40)比階段一系數(= 0.43)有所下降, 但下降的值極小, 間接效應只占總效應的10%, 進一步Sobel檢驗顯示, 認知解離在ACT與心理健康結果改變之間的中介作用不顯著(= 1.39,= 0.17 )。

3.2.4 此時此刻

納入14項RCTs研究, 樣本量1613, 最主要測量工具為五因素正念問卷(Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire, FFMQ) (例如, Eilenberg et al., 2017), 還有部分研究使用肯塔基正念技能問卷(Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills, KIMS) (Forman et al., 2007; Gumley et al., 2017; White et al., 2011), 費城正念問卷(Philadelphia Mindfulness Scale, PMS) (Levin et al., 2017b; Levin, Haeger, Pierce, & Cruz, 2017a)和正念注意覺察量表(Mindful Attention Awareness Scale, MAAS) (Clarke et al., 2014)。在納入的研究中, 主要使用抑郁(= 7)作為結果測量, 其次是整體精神癥狀(= 6)。

合并效應值的三個相關系數都具有高顯著性(見表1)且異質性顯著(= 674.31,< 0.001), 具有較大異質性(> 89%)。在此時此刻作為中介變量的路徑模型檢驗中, ACT對心理健康結果的改變路徑(= 0.21), 比直接路徑(= 0.30)有顯著下降, 但仍然保持著顯著水平, Sobel檢驗顯示, 此時此刻ACT與心理健康結果改變之間的中介作用顯著(= 2.89,= 0.003), 說明此時此刻在二者的關系中起到部分中介的作用。

3.2.5 價值

納入5篇RCTs的研究文獻, 樣本量285, 主要測量工具為個人價值問卷(Personal Values Questionnaire, PVQ) (Levin et al., 2016), 價值問卷(Valuing Questionnaire, VQ) (Levin et al., 2017b), 慢性疼痛價值問卷(Chronic Pain Values Inventory, CPVI) (Alonso-Fernández, López-López, Losada, González, & Wetherell, 2013; Johnston, Foster, Shennan, Starkey, & Johnson, 2010), 價值生活問卷(Valued Living Questionnaire, VLQ) (Clarke, Taylor, Lancaster, & Remington, 2015; Stafford-Brown & Pakenham, 2012)。在納入的5篇研究中, 使用整體精神癥狀(= 3)和抑郁(= 2)作為結果測量。合并效應值的三個相關系數都具有高顯著性(見表1), M具有較高的異質性(= 0.77), 因此仍然支持使用隨機效應模型。在價值作為中介變量的路徑模型檢驗中, ACT的對心理健康結果的改變路徑(= 0.08), 比直接路徑(= 0.16)有顯著下降, 且不顯著, Sobel檢驗顯示, 價值在ACT與心理健康結果改變之間的中介作用顯著(= 2.16,= 0.03)。

3.3 ACT相較之傳統CBT作用機制的檢驗

以ACT作為干預組, 傳統CBT作為控制組, 考察相較之傳統CBT組, ACT的作用機制是否依然能被檢驗到。以心理靈活性作為假設的中介機制, 納入研究文獻8篇(RCTs = 7, 準實驗 = 1), 樣本量517, 使用整體精神癥狀(= 4)和焦慮(= 4)作為結果測量。合并效應值的三個相關系數異質性較低(< 37%), 且不顯著(= 22.15,= 0.39)。在中介的路徑模型檢驗中, 與傳統CBT比較, ACT對心理健康結果的改變路徑(= 0.11), 比直接路徑(= 0.12)有所下降, 但仍然保持著顯著水平, 直接效應值為0.12, 間接效應值為0.02, Sobel檢驗顯示, 中介作用顯著(= 2.02,= 0.04), 說明心理靈活性在二者的關系中起到部分中介的作用。

3.4 基于網絡傳播機制檢驗

特別考察ACT在基于網絡傳播的研究中, 以心理靈活性作為假設的中介機制是否依然能夠得以檢驗。納入6項RCT效果量(4篇文獻), 樣本量681, 主要使用抑郁(= 5)作為結果測量。TSSEM的第一階段異質性檢驗分析顯示, 合并效應值的三個相關系數都具有高顯著性(見表1), 且異質性水平顯著(= 37.02,< 0.001), X、M異質性水平較低(分別為18%和34%), 而Y異質性水平為71%。TSSEM的第二階段分析顯示, 在中介的路徑模型檢驗中, 基于網絡傳播的ACT對心理健康結果的改變路徑(= 0.11), 相較之直接路徑(= 0.17)有所下降, 但仍然保持著顯著水平, 直接效應值為0.22, 間接效應值為0.06, Sobel檢驗顯示, 中介作用顯著(= 3.6,< 0.001), 說明心理靈活性在二者的關系中起到部分中介的作用。

4 討論

本研究采用MASEM的方法, 系統檢驗了ACT所假設的作用機制。其一, 在疼痛障礙、人格障礙、抑郁(障礙)、焦慮(障礙)、物質濫用、職業倦怠等不同群體, ACT所假設的心理靈活性、接納、此時此刻、價值的中介作用都達到統計顯著, 認知解離這一中介變量并不顯著, 而以已為景和承諾行動因各只納入一篇研究無法進行MASEM分析。其二, 這些機制在網絡化干預中仍然得到檢驗, 說明ACT的治療機制具有可遷移性。

其三, ACT在其所假設的改變機制上, 即心理靈活性及其所包含的6大成分, 較傳統CBT具有優勢。與以往的元分析發現較為一致(Dimidjian et al., 2016)的是ACT在其相關聯的過程變量改變上, 相較之傳統CBT, 具有中等后測效果量(= 0.45)。但應看到的, 在與傳統CBT的對比中, 本元分析納入的研究多數僅測量了心理靈活性。ACT對特定機制具有更大效果量, 并不意味著治療效果更好, 目前元分析的證據并無法得出ACT比傳統CBT更有效的結論(Dimidjian et al., 2016; Hacker et al., 2016; ?st, 2008; ?st, 2014; Powers, V?rding, & Emmelkamp, 2009), 但是, 正如共同因素說所主張的“渡渡鳥效應”, 凡是有效的治療機制都應該被獎勵, 這有助于后續研究進一步厘清不同治療方法共同的作用機制。正如ACT與以人為中心治療的比較研究中發現的: 以人為中心療法對ACT所提出的心理靈活性具有同等的改變效果(Lang et al., 2017)。

值得注意的是, ACT中認知解離的中介效應不顯著。可能的原因是, 在納入測量認知解離的9篇文獻中, 有3篇的對照組是傳統CBT或CT組(Clarke et al., 2014; Hancock & Swain, 2016; Hancock et al., 2016; Zettle et al., 2011), 而ACT與傳統CBT (或CT)可能都發生了認知解離。

不少研究者認為, ACT所提出的認知解離和傳統CBT的認知重建概念具有異曲同工之處(Dimidjian et al., 2016; Swain et al., 2015), 研究者推測二者可能有潛在相同的作用機制(Forman et al., 2012)。雖然傳統CBT并沒有明確討論認知解離, 但有研究提供了證據, 即認知解離不僅在ACT中發生改變, 在傳統CBT中同樣發生(Arch et al., 2012); 而ACT療法也同樣改變了傳統CBT中所強調的功能失調性思維(任志洪等, 2016)。認知解離被定義為減少認知的字面性質, 其結果是“通常減少對個體事件的可信度或依附性”(Hayes et al., 2006), 換言之, 把負性思維看作一種行為, 從而更好地把事件與所衍生的意義分離(Larsson, Hooper, Osborne, Bennett, & McHugh, 2016)。而在傳統CBT中, 這種現象也被稱為元認知覺察(metacognitive awareness), 即“負性思維認知……被看作是個體經歷的心理事件, 而非自我本身”(Takahashi, Muto, Tada, & Sugiyama, 2002)。這些證據表明了ACT認知解離與傳統CBT認知重建的重疊性, 即降低認知的可信度。如何降低認知可信度呢? 有研究者進一步指出, 認知重建和接納有助于降低對心理事件的抑制和心理回避, 而這過程包括聚焦、識別和打斷消極思維, 這可能也是一種暴露形式(Swain et al., 2015); 而ACT的諸多練習, 比如單詞游戲(單詞重復、搞怪聲音、慢說話、唱出思維、單詞翻譯), 這些暴露程序使當事人反復接觸高頻度的相關刺激, 直到其語言所引出的功能減弱(Assaz, Roche, Kanter, & Oshiro, 2018)。簡言之, 暴露可能是認知解離與認知重建共同的作用機制。

本研究的局限: (1)本研究僅關注隨機和非隨機對照組研究, 而其他類型的研究, 比如個案研究, 可能可以為ACT的作用機制在治療過程中的變化提供更為深入的理解; (2)所納入的實證研究, 其研究對象、精神障礙或心理問題類型不盡相同, 各項實證研究的具體操作和數據收集方法具有差異。這也正是元分析一直存在的“蘋果和橙子問題” (apple and orange problem); 但納入元分析的實證研究也具有共性, 都關注ACT對精神障礙或心理問題的治療效果, 這些共性是元分析得以進行的基礎。(3)從理論假設上來說, 6個成分應是一階因素, Hayes用心理靈活性一詞作為6大機制的統稱, 那么心理靈活性應該是二階因素。所以, 可能存在更為復雜的機制模型, 比如, ACT治療→某個ACT成分→心理靈活性→治療效果, 或者是: ACT治療→心理靈活性→某個ACT成分變化→治療效果。然而, 元分析是基于已有實證研究的再分析, 而在納入的實證研究中極少同時測量了心理靈活性及6大成分, 因此在本研究中, 我們無法檢驗更為復雜的ACT作用機制模型。(4) MASEM方法本身具有一定的局限性, 特別是本研究對作用機制的考察報告了Sobel經典中介檢驗結果, 該法近年來也受到正態分布假設和統計功效較低的詬病(MacKinnon, et al., 2007); 且應該注意到, 原始研究中其中介變量和治療結果變量的測量方法可能存在共同測量偏差, 本研究結果可能也受其影響。

5 臨床研究啟示

(1)應盡可能全面測量ACT的6大核心機制。現有研究主要使用的AAQ和AAQ-II更趨向于測量全局的心理靈活性, 而對6大具體核心機制的檢驗較少。許多研究并沒有同時測量6大作用機制, 可能是其測量工具上的不便, 不同的機制使用了不同的測量工具。因而, 最近有研究者開發同時測量ACT六大成分的測量工具(Francis, Dawson, & Golijani-Moghaddam, 2016), 雖然其信效度仍需臨床研究進一步檢驗。

(2)現有對ACT的研究聚集于癥狀的改善, 后續研究應關注其對美好生活提升的影響。一些觀點認為, ACT的6大機制可以分為三大模塊(Villatte et al., 2016): 接納和認知解離屬于“開放”模塊, 目的是降低思維、情感和感覺的有害反應; 價值和承諾行動屬于“行動”模塊, 側重強化動機和增加有意義行為; 而接觸當下和以已為景主要是為了促進自我覺察, 在“開放”和“行動”模塊中都包含, 但并沒有特意強調。就納入本元分析的文獻而言, 多數研究聚集的是“開放”模塊, 而對“行動”模塊的關注較少。事實上, “行動”模塊具有極為重要的意義。一方面是, 接納承諾療法倡導者Hayes一再強調應該把該療法的縮寫“ACT” (Acceptance and Commitment Therapy)讀成Act (行動), 而不是逐字母讀成“A-C-T”, 以體現該療法中“承諾行動”的重要性; 另一方面, 在積極心理學的影響下, 心理健康的雙因素模型認為, 心理健康并非僅是沒有心理疾病, 還應有較高的幸福感(Keyes, Shmotkin, & Ryff, 2002)。聚集于接納和認知解離的干預機制在降低心理疾病癥狀上有較大效果; 而價值和承諾行動則更有助于提升幸福感水平(Villatte et al., 2016)。此外, 對很多癥狀來說, 特別是一些與軀體相關的心理癥狀, 比如疼痛障礙, 其生理和心理癥狀本身可能并不能徹底根除, 這就需要當事人學會與癥狀較長時間相處, 那么幫助當事人尋求過與自己價值一致的生活, 就顯得尤為重要。

(3)研究設計上建議基于RCT多點測量, 結合瞬時評價方法。幾乎所有的研究都沒有滿足治療研究中介變量檢驗的要求。可能識別中介變量研究的最大挑戰是證明中介變量的改變而導致癥狀的改變這一因果關系。因此, 盡管經過30多年的過程研究, 仍無法對心理治療的改變機制有清晰、明確的實驗解釋(Lemmens et al., 2016)。即使是旨在考察治療改變的因果過程研究, 欲證明因果關系也是很困難的。首先, 確定觀測的最佳時間和間隔, 以捕獲治療改變的臨界點, 是一件困難而微妙的事情, 特別是在治療的變化速度和形態并沒有先驗信息的情況下。研究者需要在最優化研究設計、當事人負擔和對數據過多測量所造成的測量假象風險等方面獲得平衡(Longwell & Truax, 2005)。此外, 研究設計通常是基于治療改變是漸進和線性的假設。然而, 各種研究表明, 改變經常是突然發生的, 而不是在治療過程中逐漸發生(Aderka, Nickerson, B?e, & Hofmann, 2012)。如果治療確實是突然獲益(例如“啊哈體驗”), 那么抓住這一時刻可能非常困難, 更不用說評估機制變化與癥狀改變之間的時序關系(Lemmens et al., 2016)。然而, 隨著網絡化干預發展, 特別是基于手機APP干預應用的嘗試(Levin et al., 2017a), 結合當事人主動報告瞬時評價的日常經驗取樣法(Experience Sampling Method) (Hektner, Schmidt, & Csikszentmihalyi, 2007)去捕獲干預的突然獲益逐漸成為可能, 這將有助于厘清改變機制。

(4)在傳統中介檢驗法的基礎上, 盡可能使用更高級、更先進的統計方法。根據Kazdin (2007)治療中介檢驗的建議, 現有治療機制檢驗多數采用推薦的Bootstrap法進行中介檢驗(Preacher & Hayes, 2008)。而一些研究者認為, 僅通過前后測(或追蹤)探索治療的改變機制是不足夠的, 要考察治療過程中介變量和結果變量的變化趨勢, 應該在治療期間對二者進行多點測量(Black & Chung, 2014)。極少ACT研究者開始在每次治療單元都進行機制和效果測量, 并使用與多點測量相對應的縱向中介模型分析; 而已有研究大多采用混合效應回歸模型, 即以時間、中介變量和結果變量為層一, 被試個體間差異為層二, 以考察隨著時間變化每干預單元機制與結果變量的變化情況(Forman et al., 2012; Kemani et al., 2016)。然而, 近年來新發展的縱向中介模型分析技術(Grimm, Ram, & Estabrook, 2017), 比如潛變量增長曲線模型(Latent Growth Curve Models, LGCM)、潛變量變化分數模型(Latent Change Score Models)和多水平結構方程模型(Multilevel Structural Equation Modeling)也應值得嘗試。

6 結論

本研究采用元分析結構方程模型, 通過對50篇ACT研究中介機制的檢驗, 得出以下結論:(1) ACT所假設的心理靈活性、接納、此時此刻、價值的中介作用都達到統計顯著; 認知解離這一中介變量并不顯著; (2) ACT在所假設的機制上有其區別于傳統CBT的優勢; (3)這些機制在網絡化干預中仍然得到檢驗, 說明ACT治療的機制具有可遷移性。

Aderka, I. M., Nickerson, A., B?e, H. J., & Hofmann, S. G. (2012). Sudden gains during psychological treatments of anxiety and depression: A meta-analysis.(1), 93–101.

Alonso-Fernández, M., López-López, A., Losada, A., González, J. L., & Wetherell, J. L. (2013). Acceptance and commitment therapy and selective optimization with compensation for institutionalized older people with chronic pain: A pilot study.(2), 264–277.

Alsubaie, M., Abbott, R., Dunn, B., Dickens, C., Keil, T. F., Henley, W., & Kuyken, W. (2017). Mechanisms of action in mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) and mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) in people with physical and/or psychological conditions: A systematic review.55, 74–91.

Arch, J. J., Eifert, G. H., Davies, C., Vilardaga, J. C. P., Rose, R. D., & Craske, M. G. (2012). Randomized clinical trial of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) versus acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) for mixed anxiety disorders.(5), 750–765.

Assaz, D. A., Roche, B., Kanter, J. W., & Oshiro, C. K. B. (2018). Cognitive defusion in acceptance and commitment therapy: What are the basic processes of change.(4), 405–418.

A-Tjak, J. G. L., Davis, M. L., Morina, N., Powers, M. B., Smits, J. A. J., & Emmelkamp, P. M. G. (2015). A meta-analysis of the efficacy of acceptance and commitment therapy for clinically relevant mental and physical health problems.(1), 30–36.

Avdagic, E., Morrissey, S. A., & Boschen, M. J. (2014). A randomised controlled trial of acceptance and commitment therapy and cognitive-behaviour therapy for generalised anxiety disorder.(2), 110–130.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations(6), 1173–1182.

Beck, A. T. (1993). Cognitive therapy: Past, present, and future.(2), 194–198.

Black, J. J., & Chung, T. (2014). Mechanisms of change in adolescent substance use treatment: How does treatment work?.(4), 344–351.

Bluett, E. J., Homan, K. J., Morrison, K. L., Levin, M. E., & Twohig, M. P. (2014). Acceptance and commitment therapy for anxiety and OCD spectrum disorders: An empirical review.(6), 612–624.

Bond, F. W., Hayes, S. C., Baer, R. A., Carpenter, K. M., Guenole, N., Orcutt, H. K., … Zettle, R. D. (2011). Preliminary psychometric properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II: A revised measure of psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance.(4), 676–688.

Cheung, M. L., & Chan, W. (2005). Meta-analytic structural equation modeling: A two stage approach.(1), 40–64.

Cheung, M. W. L. (2014). Fixed- and random-effects meta-analytic structural equation modeling: Examples and analyses in R.(1), 29–40.

Cheung, M. W. L. (2015).Chichester, West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

Clarke, S., Kingston, J., James, K., Bolderston, H., & Remington, B. (2014). Acceptance and commitment therapy group for treatment-resistant participants: A randomized controlled trial.(3), 179–188.

Clarke, S., Taylor, G., Lancaster, J., & Remington, B. (2015). Acceptance and commitment therapy–based self-management versus psychoeducation training for staff caring for clients with a personality disorder: A randomized controlled trial.(2), 163–176.

Cohen, J., Jr. (1988):(2nd Edition.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Dimidjian, S., Arch, J. J., Schneider, R. L., Desormeau, P., Felder, J. N., & Segal, Z. V. (2016). Considering meta-analysis, meaning, and metaphor: A systematic review and critical examination of “Third Wave” cognitive and behavioral therapies.(6), 886–905.

Eilenberg, T., Hoffmann, D., Jensen, J. S., & Frostholm, L. (2017). Intervening variables in group-based acceptance & commitment therapy for severe health anxiety., 24–31.

Eustis, E. H., Hayes-Skelton, S. A., Roemer, L., & Orsillo, S. M. (2016). Reductions in experiential avoidance as a mediator of change in symptom outcome and quality of life in acceptance-based behavior therapy and applied relaxation for generalized anxiety disorder., 188–195.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences.(2), 175–191.

Forman, E. M., Chapman, J. E., Herbert, J. D., Goetter, E. M., Yuen, E. K., & Moitra, E. (2012). Using session-by-session measurement to compare mechanisms of action for acceptance and commitment therapy and cognitive therapy.(2), 341–354.

Forman, E. M., Herbert, J. D., Moitra, E., Yeomans, P. D., & Geller, P. A. (2007). A randomized controlled effectiveness trial of acceptance and commitment therapy and cognitive therapy for anxiety and depression.(6), 772–799.

Francis, A. W., Dawson, D. L., & Golijani-Moghaddam, N. (2016). The development and validation of the comprehensive assessment of acceptance and commitment therapy processes (CompACT).(3), 134–145.

Grimm, K. J., Ram, N., & Estabrook, R. (2017).New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Gu, J., Strauss, C., Bond, R., & Cavanagh, K. (2015). How do mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction improve mental health and wellbeing? A systematic review and meta-analysis of mediation studies., 1–12.

Gumley, A., White, R., Briggs, A., Ford, I., Barry, S., Stewart, C., … McLeod, H. (2017). A parallel group randomised open blinded evaluation of acceptance and commitment therapy for depression after psychosis: Pilot trial outcomes (ADAPT)., 143–150.

Hacker, T., Stone, P., & MacBeth, A. (2016). Acceptance and commitment therapy-Do we know enough? Cumulative and sequential meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials., 551–565.

Hancock, K., & Swain, J. (2016). Long term follow up in children with anxiety disorders treated with acceptance and commitment therapy or cognitive behavioral therapy: Outcomes and predictors.(5), 317–329.

Hancock, K. M., Swain, J., Hainsworth, C. J., Dixon, A. L., Koo, S., & Munro, K. (2016). Acceptance and commitment therapy versus cognitive behavior therapy for children with anxiety: Outcomes of a randomized controlled trial.(2), 296–311.

Hayes, S. C. (2004).New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J. B., Bond, F. W., Masuda, A., & Lillis, J. (2006). Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes and outcomes.(1), 1–25.

Hayes, S. C., Villatte, M., Levin, M., & Hildebrandt, M. (2011). Open, aware, and active: Contextual approaches as an emerging trend in the behavioral and cognitive therapies., 141–168.

Hektner, J. M., Schmidt, J. A., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2007).Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Higgins, J. P. T., & Thompson, S. G. (2002). Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis.(11), 1539–1558.

Hofmann, S. G., & Asmundson, G. J. G. (2008). Acceptance and mindfulness-based therapy: New wave or old hat?(1), 1–16.

Johnston, M., Foster, M., Shennan, J., Starkey, N. J., & Johnson, A. (2010). The effectiveness of an acceptance and commitment therapy self-help intervention for chronic pain.(5), 393–402.

Juarascio, A., Shaw, J., Forman, E., Timko, C. A., Herbert, J., Butryn, M., … Lowe, M. (2013). Acceptance and commitment therapy as a novel treatment for eating disorders: An initial test of efficacy and mediation.(4), 459–489.

Kazdin, A. E. (2007). Mediators and mechanisms of change in psychotherapy research.(1), 1–27.

Kemani, M. K., Hesser, H., Olsson, G. L., Lekander, M., & Wicksell, R. K. (2016). Processes of change in acceptance and commitment therapy and applied relaxation for long-standing pain.(4), 521–531.

Keyes, C. L. M., Shmotkin, D., & Ryff, C. D. (2002). Optimizing well-being: The empirical encounter of two traditions.(6), 1007–1022.

Lang, A. J., Schnurr, P. P., Jain, S., He, F., Walser, R. D., Bolton, E., ... Strauss, J. (2017). Randomized controlled trial of acceptance and commitment therapy for distress and Impairment in OEF/OIF/OND veterans.(S1), 74–84.

Lappalainen, P., Langrial, S., Oinas-Kukkonen, H., Tolvanen, A., & Lappalainen, R. (2015). Web-based acceptance and commitment therapy for depressive symptoms with minimal support: A randomized controlled trial.(6), 805–834.

Larsson, A., Hooper, N., Osborne, L. A., Bennett, P., & McHugh, L. (2016). Using brief cognitive restructuring and cognitive defusion techniques to cope with negative thoughts.(3), 452–482.

Lemmens, L. H. J. M., Müller, V. N. L. S., Arntz, A., & Huibers, M. J. H. (2016). Mechanisms of change in psychotherapy for depression: An empirical update and evaluation of research aimed at identifying psychological mediators., 95–107.

Levin, M. E., Haeger, J., Pierce, B., & Cruz, R. A. (2017a). Evaluating an adjunctive mobile app to enhance psychological flexibility in acceptance and commitment therapy.(6), 846–867.

Levin, M. E., Haeger, J. A., Pierce, B. G., & Twohig, M. P. (2017b). Web-based acceptance and commitment therapy for mental health problems in college students: A randomized controlled trial.(1), 141–162.

Levin, M. E., Hayes, S. C., Pistorello, J., & Seeley, J. R. (2016). Web-based self-help for preventing mental health problems in universities: Comparing acceptance and commitment training to mental health education.(3), 207–225.

Levin, M. E., Pistorello, J., Seeley, J. R., & Hayes, S. C. (2014). Feasibility of a prototype web-based acceptance and commitment therapy prevention program for college students.(1), 20–30.

Lipsey, M. W., & Wilson, D. B. (2001).Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Lloyd, J., Bond, F. W., & Flaxman, P. E. (2013). The value of psychological flexibility: Examining psychological mechanisms underpinning a cognitive behavioural therapy intervention for burnout.(2), 181–199.

Longwell, B. T., & Truax, P. (2005). The differential effects of weekly, monthly, and bimonthly administrations of the beck depression inventory-II: Psychometric properties and clinical implications.(3), 265–275.

Luciano, J. V., Guallar, J. A., Aguado, J., Lopez-del-Hoyo, Y., Olivan, B., Magallon, R., … Garcia-Campayo, J. (2014). Effectiveness of group acceptance and commitment therapy for fibromyalgia: A 6-month randomized controlled trial (EFFIGACT study).(4), 693–702.

MacKinnon, D. P., Fairchild, A. J., & Fritz, M. S. (2007). Mediation analysis.(1), 593–614.

Millstein, D. J., Orsillo, S. M., Hayes-Skelton, S. A., & Roemer, L. (2015). Interpersonal problems, mindfulness, and therapy outcome in an acceptance-based behavior therapy for generalized anxiety disorder.(6), 491–501.

Montazemi, A. R., & Qahri-Saremi, H. (2015). Factors affecting adoption of online banking: A meta-analytic structural equation modeling study.(2), 210–226.

Morris, S. B. (2008). Estimating effect sizes from pretest-posttest-control group designs.(2), 364–386.

?st, L. G. (2008). Efficacy of the third wave of behavioral therapies: A systematic review and meta-analysis.(3), 296–321

?st, L. G. (2014). The efficacy of acceptance and commitment therapy: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis., 105–121.

Orwin, R. G. (1994). Evaluating coding decisions. In H. Cooper., & L. V. Hedges (Eds.),(pp. 139–162). New York, NY, US: Russel Sage Foundation.

Powers, M. B., V?rding, M. B. Z. V. S., & Emmelkamp, P. M. G. (2009). Acceptance and commitment therapy: A meta-analytic review.(2), 73–80.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models.(3), 879–891.

Ren, Z. H., Li, X. Y., Zhao, L. B, Yu, X. L., Li, Z. H., Lai, L. Z, ... Jiang, G. R. (2016). Effectiveness and mechanism of internet-based self-help intervention for depression: The Chinese version of MoodGYM.(7), 818–832.

[任志洪, 李獻云, 趙陵波, 余香蓮, 李政漢, 賴麗足, … 江光榮. (2016). 抑郁癥網絡化自助干預的效果及作用機制——以漢化MoodGYM為例.(7), 818–832.]

Rost, A. D., Wilson, K., Buchanan, E., Hildebrandt, M. J., & Mutch, D. (2012). Improving psychological adjustment among late-stage ovarian cancer patient: Examining the role of avoidance in treatment.(4), 508–517.

Rothstein, H., Sutton, A. J., & Borenstein, M. (2005).Chichester, West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

Ruiz, F. J. (2012). Acceptance and commitment therapy versus traditional cognitive behavioral therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of current empirical evidence.(3), 333–357.

Schmidt, F. L., & Hunter, J. E., (2015).(3rd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Stafford-Brown, J., & Pakenham, K. I. (2012). The effectiveness of an act informed intervention for managing stress and improving therapist qualities in clinical psychology trainees.(6), 592–513.

Swain, J., Hancock, K., Hainsworth, C., & Bowman, J. (2015). Mechanisms of change: Exploratory outcomes from a randomised controlled trial of acceptance and commitment therapy for anxious adolescents.(1), 56–67.

Takahashi, M., Muto, T., Tada, M., & Sugiyama, M. (2002). Acceptance rationale and increasing pain tolerance: Acceptance-based and Fear-based practice., 35–46.

Trompetter, H. R., Bohlmeijer, E. T., Veehof, M. M., & Schreurs, K. M. G. (2015). Internet-based guided self-help intervention for chronic pain based on acceptance and commitment therapy: A randomized controlled trial.(1), 66–80.

Villatte, J. L., Vilardaga, R., Villatte, M., Plumb Vilardaga, J. C., Atkins, D. C., & Hayes, S. C. (2016). Acceptance and commitment therapy modules: Differential impact on treatment processes and outcomes., 52–61.

Viswesvaran, C., & Ones, D. S. (1995). Theory testing: Combining psychometric meta‐analysis and structural equations modeling.(4), 865–885.

Wampold, B. E. (2013).New York, NY:Routledge.

Wampold, B. E., & Imel, Z. E. (2015).(2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Waters, C. S., Frude, N., Flaxman, P. E., & Boyd, J. (2018). Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) for clinically distressed health care workers: Waitlist-controlled evaluation of an ACT workshop in a routine practice setting.(1), 82–98.

Westin, V. Z., Schulin, M., Hesser, H., Karlsson, M., Noe, R. Z., Olofsson, U., … Andersson, G. (2011). Acceptance and commitment therapy versus tinnitus retraining therapy in the treatment of tinnitus: A randomised controlled trial.(11), 737–747.

Wetherell, J. L., Afari, N., Rutledge, T., Sorrell, J. T., Stoddard, J. A., Petkus, A. J., … Atkinson, J. H. (2011). A randomized, controlled trial of acceptance and commitment therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic pain.(9), 2098–2107.

White, R., Gumley, A., McTaggart, J., Rattrie, L., McConville, D., Cleare, S., & Mitchell, G. (2011). A feasibility study of acceptance and commitment therapy for emotional dysfunction following psychosis.(12), 901–907.

Wicksell, R. K., Ahlqvist, J., Bring, A., Melin, L., & Olsson, G. L. (2008). Can exposure and acceptance strategies improve functioning and life satisfaction in people with chronic pain and whiplash-associated disorders (WAD)? A randomized controlled trial.(3), 169–182.

Wicksell, R. K., Kemani, M., Jensen, K., Kosek, E., Kadetoff, D., Sorjonen, K., … Olsson, G. L. (2013). Acceptance and commitment therapy for fibromyalgia: A randomized controlled trial.(4), 599–611.

Yadavaia, J. E., Hayes, S. C., & Vilardaga, R. (2014). Using acceptance and commitment therapy to increase self-compassion: A randomized controlled trial.(4), 248–257.

Zarling, A., Lawrence, E., & Marchman, J. (2015). A randomized controlled trial of acceptance and commitment therapy for aggressive behavior.(1), 199–212.

Zeng, X. L., Liu, X. P., & Yu, S. (2011). The theoretical background, empirical study and future development of the acceptance and commitment therapy.(7), 1020–1026.

[曾祥龍, 劉翔平, 于是. (2011). 接納與承諾療法的理論背景、實證研究與未來發展.(7), 1020–1026.]

Zettle, R. D., Rains, J. C., & Hayes, S. C. (2011). Processes of change in acceptance and commitment therapy and cognitive therapy for depression: A mediation reanalysis of Zettle and Rains.(3), 265–283.

Zhang, Q., Wang, S. J., & Zhu, Z. H. (2012). Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT): Psychopathological model and processes of change.(5), 377–381.

[張婍, 王淑娟, 祝卓宏 (2012). 接納與承諾療法的心理病理模型和治療模式.(5), 377–381.]

[1]納入的元分析文獻及特征編碼, 請見電子版的附表。

Mechanisms of the Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: A meta-analytic structural equation model

REN Zhihong; ZHAO Chunxiao; BIAN Cheng; ZHU; Wenzhen; JIANG Guangrong; ZHU Zhuohong

(Key Laboratory of Adolescent Cyberpsychology and Behavior (CCNU), Ministry of Education; School of Psychology, Central China Normal University; Key Laboratory of Human Development and Mental Health of Hubei Province, Wuhan 430079, China) (State Key Laboratory of Cognitive Neuroscience and Learning, IDG/McGovern Institution for Brain Research, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, 100875, China) (University of North Texas, Texas, 76203, United States) (Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences; The Key Laboratory of Mental Health, Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China)

Following the Behavioral Therapy and the Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT), Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) is considered as one of the third wave of behavioral therapies. ACT is based on the relational frame theory, and its therapeutic model includes 6 components (i.e., acceptance, cognitive defusion, self-as-context, committed action, contact with the present moment, values) and psychological flexibility. What is the empirical evidence for these hypothesized components or mechanisms? In recent years, integrating meta-analysis and structural equation modeling, the meta-analytic structural equation model (MASEM) has made it possible to systematically examine the mechanisms of psychotherapy. Compared to the traditional single randomized controlled trial (RCT) studies, the MASEM combines multiple samples to increase statistical power and obtain more robust model estimates. The current study utilized two-stage structural equation modeling (TSSEM) to examine three aspects of the mechanisms of ACT, including: (1) the mediational effects of psychological flexibility and the 6 components, (2) the unique mechanisms of ACT compared to CBT, and (3) the generalizability of these mechanisms to internet-based ACT interventions.

Studies were identified by searching Web of science, PsycARTICLES, PsycINFO, Pubmed, Elsevier, EBSCO, Wiley Online Library from the first available date until November, 2017. We used the search term Acceptance and Commitment Therapy combined with acceptance, cognitive defusion, self-as-context, committed action, contact with the present moment, values, or psychological flexibility. Selection criteria included: (1) adult sample (age > 18), (2) RCT or quasi-experimental design, which measured pre-post change with ACT interventions, (3) quantitative measures of psychological outcomes (clinical or non-clinical) before and after treatment, and (4) quantitative measures of mediational variables at pre and post treatment. Excluding criteria were (1) not having a control group, (2) mixed intervention studies, which integrated ACT with other interventions, or included the Acceptance component but not the complete ACT model, or used CBT with the Acceptance component, and (3) medication treatment as the control group. The metaSEM package in R was used for the TSSEM analysis to examine the mechanisms of ACT.

The literature search resulted in 50 studies, involving issues such as pain disorder, personality disorder, depression, anxiety, substance abuse, and work-related burnout among healthy populations. Most studies examined psychological flexibility (= 39), followed by contact with the present moment (= 14), acceptance (= 6), cognitive defusion (= 9), and values (= 5), whereas the studies of self-as-context (= 1) and committed action (= 1) were excluded from further MASEM analysis due to a low number of publications. Results indicated that (1) the mediational effects of psychological flexibility, acceptance, contact with the present moment, and values were significant, while the effects of cognitive defusion were not significant, (2) the mechanisms of ACT are evident in internet-based interventions, suggesting the generalizability of these mechanisms, and (3) compared to the traditional CBT, the hypothesized mechanisms of ACT have their unique advantages.

Implications for future studies: (1) measure all 6 core mechanisms as comprehensively as possible; (2) focus more on the increase of wellbeing as opposed to improvement of symptoms; (3) use RCT based multiple measurements combined with the experience sampling method; and (4) apply more advanced statistical methods in addition to the traditional mediation statistics.

acceptance and commitment therapy; meta-analytic structural equation model; mechanism; mediational study; cognitive-behavior therapy

R395

10.3724/SP.J.1041.2019.00662

2018-08-10

* 國家社科基金項目(16CSH051)資助。

祝卓宏, E-mail: zhuzh@psych.ac.cn