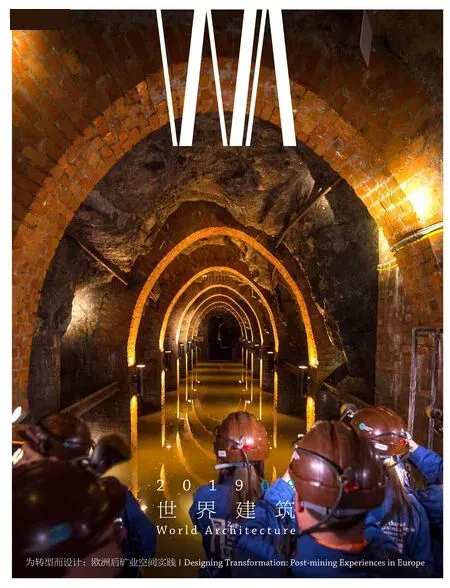

歐洲礦業經歷與為轉型而設計

卡羅拉·S·諾伊格鮑爾,安娜·瑪利克·韋伯,克里斯塔·萊歇爾/Carola S. Neugebauer, Anna Marijke Weber, Christa Reicher陳茜 譯/Translated by CHEN Xi

1 礦業經歷

自中世紀早期以來,采礦業及其擴張、技術發展與衰敗的各個階段深刻塑造了歐洲的空間與人。德國的厄爾士山脈就令人回想起這段悠久歷史及其遺產。2019 年7 月被評定為聯合國教科文組織世界遺產,代表厄爾士的早期礦石開采的及其多元化影響價值得到了認可。12 世紀中葉起,人們開始對銀、錫、銅、鐵等金屬進行開采,15 世紀采礦業的擴張,不僅帶來了“前資本主義的經濟融資體系”和“用于深井開采的新技術與其他創新”[1]7,同時也誕生了一批礦工定居點和城鎮。基督教信仰深刻錨固于礦工們的思想意識中,宗教傳統反過來也成為了采礦的精神符號。由于采礦業的起起伏伏,經濟發展的替代性分支產業獲得發展,16 世紀時興起了如紡織品、玻璃、紙張、鐘表等手工制造業以及木工行業(玩具制造),到19 世紀則迎來了汽車工程、機械工程與工具工業[1]8。大學的建立與這些發展緊密相關[2]。在德國戈斯拉爾的哈茨山區、俄羅斯的烏拉爾山脈、瑞典的法倫、英國的德文郡和康沃爾及斯洛伐克的班斯卡什佳夫尼察,前現代礦業開采的歷史也以與之類似又各具特色的方式塑造了當地的人與空間。

工業化將采礦業帶向鼎盛時期。魯爾地區的硬煤開采就是其中的代表。在19 世紀,鐵路的建造和蒸汽機的使用,令魯爾河實現了通航,奠定了該地區進行高度工業化采礦的基礎,因而使得工業化的深井采煤成為可能。區域內的中世紀城市也蛻變成為工業城市,并經歷了幾次國際移民浪潮。20 世紀上半葉硬煤開采的擴張的同時,化學工業、國防工業以及電力行業等新興產業相伴發展。高度工業化的煤炭和鋼鐵產業集群令所在地區遭到了嚴重的環境破壞(大量的空氣和水污染),這樣的變化也引發了外部對整個區域的負面看法。在波蘭的西里西亞和烏克蘭的頓巴斯等歐洲城市,當時的硬煤開采強度與魯爾區無異。法國的北部加來海峽地區,作為煤炭開采的早期工業重地,如今也成為了聯合國教科文組織世界遺產地。

露天褐煤開采是歐洲高度工業化采礦的另一種形式。在德國,它已在盧薩蒂亞、萊茵河流域、德國中部和黑爾姆施泰特等地區運營了150 年。由于其景觀消耗的特征,只有在歐洲的農村地區才可能進行,這樣可以使得因露天采礦而進行的居民遷移相對較少。

以上這幾例歷史的關鍵時刻,刻畫出礦業遺跡地的高度多樣化。歐洲的采礦業隨資源、技術和歷史時期而呈現出不同的面貌。這包含了物質層面及非物質層面的多種元素——如礦井與礦山,采礦技術設備與相關貿易,定居點與景觀以及被采礦業塑造并強化的手工藝、美術、音樂、文學、語言和宗教實踐的傳統。此外,上述案例均揭示了采礦這一產業在各地區及當地居民的經濟、社會文化與生態發展之間創造的緊密且復雜的關聯。采礦并非純粹的單領域經濟活動,也是景觀和環境資源、聚居點居民及其日常生活、知識與文化的構成要素。

2 后礦業挑戰

幾個世紀以來,當地居民多是自發地不斷適應著采礦產業的衰敗所帶來的后果。礦廠關閉后,他們轉移到相關的工業產業,多多少少算是成功進入了替代經濟領域的發展,還有一些移民到其他地方。大自然重新奪回了對廢棄采礦地的主權。只有在20 世紀下半葉,工業化開采對空間和社會產生嚴重而深刻的影響之時,對后礦業多層次遺留后果的敏感程度才有所增加。如何應對其基礎影響的批判性思考開始發展,對“設計”后礦業未來的呼吁開始涌現——努力在社會、經濟和環境上都實現可持續的、整合的且平衡的轉型。大規模的后礦業轉型需要在空間層次進行設計嗎?我們如何才能實現這一目標?這樣的問題成為了話題的核心。

時至今日,該問題的重要性仍難以摘除。一方面,世界各地包括歐洲在內的開采活動與未來礦業規劃仍然繼續進行著。相關地區及其居民終歸將面臨后礦業轉型的挑戰,并努力實現最佳結果。另一方面,現今我們已然見證了上面提到的德國4 個褐煤開采區中最終面對后礦業時代的“設計”時那些具體而嚴峻的挑戰。鑒于全球范圍內不斷增長的環境保護和氣候變化意識,對化石燃料和褐煤開采的反對日益加劇,德國政府于2019 年1 月宣布,到2038 年將完全取消褐煤開采。這一決定在實際上宣告了德國大規模采礦業的結束。至少400 億歐元的國家資金被承諾用于支持露天采礦地區的基礎轉型的過程。

3 為后礦業空間轉型而設計

在此背景下,我們亟需圍繞為空間與人“設計”后礦業可持續轉變的有效方法而進行反思與探討。本期專輯為此提供了良好的契機,故在匯編過程中我們特別堅持了以下兩點原則:一,通過設計項目的比較展開以推動學習借鑒;二,借此提升對本土后礦業設計與地域化轉型方法的依賴性關聯意識。

1 Experiences of mining

Mining and its phases of expansion,technological development and decline have shaped spaces and people in Europe since the early middle ages. The Ore Mountains (Erzgebirge) in Germany reminds of this long history and heritage. The UNESCO world heritage region since July 2019 stands for the early ore mining and its various impacts. In the middle of the 12th century the mining of silver, tin, copper and iron started and its expansion in the 15th century brought about not only "pre-capitalistic economic systems of financing"and "new technologies for deep mining and other innovations"[1]7, but also mining settlements and towns. The Christian religion was anchored in the miners' consciousness and religious traditions took up symbols of mining in turn. As a result of the ups and downs in mining, alternative branches of the economy developed like the manufacturing of textiles, glass, paper, watches and the woodworking trades (toy manufacture) since the 16th century, and automotive engineering, mechanical engineering and the tool industry in the 19th century[1]8.University foundations were closely related to these developments[2]. In a similar and yet specific way, premodern ore mining was also shaped by people and spaces in the Harz region (Gosslar, Germany), the Ural Mountains (Russia), Falun in Sweden, Devon and Cornwall (England) or in Banská ?tiavnica(Slovakia).

Industrialisation brought a heyday to mining.Hard coal mining in the Ruhr region is an example of this. Here, in the 19th century, the foundations for highly industrial mining were laid by making the river Ruhr navigable, by constructing railways and by using steam engines, which made industrial deep coal mining possible. The medieval cities of the region grew into industrial cities and experienced several waves of international immigration. The expansion of hard coal mining in the first half of the 20th century was accompanied by new industries such as the chemical and defense industries and electricity generation. The highly industrialised coal and steel cluster shaped the region through severe environmental damages (massive air and water pollution) and was accompanied by a negative external perception of the whole region. Hard coal was mined at similar intensities in Europe in Silesia (Poland) and in Donbas (Ukraine). An early industrial focal point of coal mining was the region of Nord-Pas de Calais, also with UNESCO world heritage sites.

Lignite mining as opencast technique is another form of highly industrialised mining in Europe. In Germany, it has been operated for 150 years in the Lusatian, Rhine, Central German and Helmstedt districts. With its landscape-consuming character,it is possible above all in rural regions in Europe,where it means the resettlement for comparatively few people.

These few highlights of history underline the great variety of mining heritage. Mining in Europe differs according to the resource, technique and historic period of mining. It comprises material as well as immaterial layers, e.g. pits and mines,technical facilities of mining and accompanying businesses, settlements and landscapes as well as traditions of craftsmanship and religion, art, music,literature and language shaped and consolidated by mining. Moreover, the examples above underline the tight and complex connections that mining creates between the economic, socio-cultural and ecological development of the regions and their people. Mining is not a sectoral economic activity, but formative for the landscape and environmental resources, for settlements and people with their everyday lives,knowledge and culture.

2 Challenges of post-mining

Over centuries, local people mainly selfarranged with and adapted to the consequences of mining downs. When mines closed down, they shifted to adjacent industries, developed more or less successfully alternative economic spheres or emigrated to other places. The nature recaptured abandoned sites of mining. Only in the second half of the 20th century, when the industrialised mining affected harshly and deeply on spaces and society,the sensitivity to the multi-layered consequences of post-mining grew. Critical thinking developed how to cope with the fundamental impacts and calls emerged to "design" the post-mining future,striving for sustainable, integrated and balanced transformations within society, economy and environment. One question became central: How can, and do we design the great post-mining transformation in space?

This question is of unbroken relevance till today. On the one hand, there are continuing mining activities and future planning for mining worldwide and including Europe. One day, the concerned regions and people will face the challenges of postmining transition and strive at making the best out of it. On the other hand, we witness already today the concrete and large-scale challenge to "design"the post-mining era in the last, four lignite mining districts in Germany, mentioned above. In line with the worldwide growing awareness for environmental protection and climate change, which turns also against fossil fuels and lignite mining, the German government declared in January 2019 to withdraw from lignite mining by 2038. The decision ends large-scale mining in Germany in general. At least 40 billion euros of state funding is promised to support the fundamental transformation processes in the opencast-mining regions.

3 Designs for post-mining transformation

Against this background, reflections and discussions on promising approaches to "design"sustainable post-mining transitions in space and for people are highly needed. This theme issue constitutes a great opportunity to do so and we thus pursued in particular two rationales when compiling the issue: firstly, to encourage learning by comparing projects of design; secondly, to sensitise for the interdependency of local post-mining designs and regional approaches to transformation.

3.1 Comparing post-mining designs

Europe shows many and manifold projects dedicated to the revitalisation, reuse and reinterpretation of former mining sites. Enabling the comparison of contrasting as well as similar design projects is the important precondition to learn from this variety. The issue thus displays a broad array of scales, functional programmes, disciplinary approaches, esthetics and local contexts of postmining designs in Europe.

3.1 后礦業設計比較

關于前礦業地區的復興、再利用和重譯,歐洲已有豐富多樣的項目案例。提供對類似設計項目進行比較和對比的可能性條件是從案例多樣性中汲取經驗的重要前提。因此,本期專輯收錄展示了無論在尺度范圍、功能組成、學科方法、審美視角還是所在語境都呈現出廣泛差異的歐洲后礦業設計。

例如,西里西亞卡托維茲(圖1,見70 頁)、埃森和蓋爾森基興的案例展示了獨棟采礦大廈的再設計。建筑適應了新的功能需求,向今昔展示著過去的采礦歷史文化(借助博物館的形式,如魯爾博物館,見46 頁),承載新的經濟活動(如原北極星煤礦的現代化辦公樓,見56 頁;貝靈恩be-MINE的休閑設施和購物中心,圖2,見26 頁),成為教育基地或新的文化引擎(如蓋爾森基興的音樂排練中心或瓦尼的“礦坑9 號乙”,圖3、4)。

貝爾瓦爾、基律納和魯爾地區的例子補充說明了社區和景觀的尺度。它們佐證了功能植入的多樣性,如服務于居住、商業、娛樂和科學等,但特別凸顯了規劃與藝術多學科的富有成效的相互作用。原北極星煤礦開采點和申格爾貝格工人定居點(圖5,見52 頁)的案例,將建筑、城市設計、景觀與藝術做了很好的整合。

所有地方化的后礦業設計都主要是通過提出新的適應性使用方式來發掘和重新增加當地的宜居性,并在創造具有吸引力的全新開放空間的同時,修復采礦造成的環境破壞。如此一來,這些項目往往憑借中長期的規劃展現出轉型的動力:通過提出新的想法和為這些地點創造新的身份與正面認知,許多項目成功推動了經濟、社會文化和生態在短期效果基礎上的進一步轉變。案例比較顯示出,歐洲的眾多后礦業設計不僅僅是大規模的針對性設計,而且是累積式的增量項目,其發展演化可以基于各方參與者和建筑師的專業操作而持續數十年。

設計思想與創新總是隨著時間的推移不斷被重塑以適應現狀。雨果和哈塞爾煤礦的案例(見阿克塞爾·廷佩的文章,見38 頁)很好地展示了這一點。彼得·拉茨在1990 年代為北杜伊斯堡景觀公園(見60 頁)提出的“工業自然”概念,直到今天仍然啟發著后礦業公園的設計,并逐漸演變為了新的“工業化自然”的新理念:后煤礦公園成為一個再生能源的公園,從而回應了長期的宜居性提升需求和當前的資源保護的需求。

對遺跡地歷史和遺產的強烈參照是歐洲后礦業設計的另一個特征。安娜·瑪利克·韋伯在她的論文《多面性——建筑轉型的工具》(見14 頁)中更為詳盡地研究了這一點。通過對一些后礦業建筑設計的比較,她闡明了設計如何處理物質性與非物質性,如何處理真實的與關聯的后礦業地點遺產。她揭示了這些設計的相似性和差異性,從而指向了既有獨特性和創新性的張力,也有效仿可轉移性原則的結論。安娜的供稿明確指出了比較研究作為產出新知識和促進相互學習的一種策略而具有的價值。這可能會激發對上述某些觀察結果更詳細探討的進一步研究,例如,后礦業設計如何以及為何展現(或沒有)當地的轉型動力。

3.2 反思后礦業轉型中地方設計與區域方法的連結

庫恩、索洛寧娜、和哈伊杜加等作者在本期中的供稿回顧了后礦業轉型區域的尺度,引發對歐洲一些規模最大的(后)礦業區域的關注。然而除尺度外,這些文章也指向了對連結的關注,將當地后礦業設計與區域狀況及方法聯系起來,以應對復雜的后礦業轉型。

理想狀態下,兩個“設計層級”以積極的、支持性的方式相互作用。 區域方法通過諸如在財政上的統籌、指導和支持來實現對當地后礦業設計與各方轉化舉措的理想嵌合。反過來,如上所述,當地的后礦業設計可以展現轉型動力,并影響其鄰近地區或更廣范圍的發展,或作為大眾周知的地標(如魯爾博物館和北杜伊斯堡景觀公園),或作為日常生活中的被珍視與喜愛的去處。

德國魯爾地區1989-1999 年的埃姆舍爾公園國際建筑展是積極進行地方-區域連結設計的一個好例子。在魯爾區及其他案例中(參見庫恩文章中說明的皮克勒親王郡國際建筑展,66 頁),國際建筑展被印證為一種有價值的戰略性規劃方法,可以在區域層面上激發和協調當地的后礦業設計,并鼓勵國家、社會和經濟領域的各色人員投入該區域的轉型中。IBA 方法還有助于該區域空間層面轉型的總體思路和概念的設計(參見論文《歐洲地區后礦業空間轉型的設計方法》,20 頁)。

然而,區域和地方后礦業設計之間的互關并非是普適性的。在烏拉爾山脈的案例中(見82 頁),這種連結不復存在。由于在區域及更高層級上缺少政治、經濟和規劃層面的支持和關注,當地的后礦業設計只能退回到自助式操作,回到荒蕪與衰敗的浪漫主義。更廣泛的條件決定了后礦業設計在地方和區域層面的范圍、速度和轉化影響。在萊歇爾和諾伊格鮑爾的文章(見20 頁)中指出,無論是區域層級的IBA 等戰略性規劃方法,還是地方層級進行的后礦業規劃,獨自作用都不足以保證成功且可持續的后礦業轉型。倒是若干要素與舉措的相互作用似乎在歐洲案例中成效卓著。

還有曾出現并不斷出現的問題是:這些從歐洲案例中得出的結論在全球語境內具有多高的可靠程度?在中國能夠引發進一步相互學習的后礦業經驗,包括地方和區域層次的設計是什么?我們希望本期專輯可以吸引讀者關注對這些議題展開交流的可能性。□

1 波蘭西里西亞省博物館于2015年在原先的卡托維茲礦井開設了新館/Muzeum Silesia opened its new seat in the former"Katowice" mine in 2015(圖片來源/Source: Industrial Monuments Route)

2 貝靈恩be-mine的休閑設施/Leisure facilities and shopping in Beringen be-MINE

3 礦坑9號乙全貌。除了使歷史遺產重新煥發活力之外,該地還需要一個現代化舉措,將使該地的新音樂方向更加明確/Overview of Fosse 9-9bis. In addition to the revitalised historical legacy the site needed a contemporary act which would crystallise the site's new music orientation

4 礦坑9號乙Métaphone音樂廳,既是音樂廳又是城市樂器/The Métaphone in Fosse 9-9bis is a concert hall and urban musical instrument(3.4圖片來源/Sources: ?Hérault Arnod Architectures)

5 俯瞰申格爾貝格工人定居點/View of the workers' settlement of Schüngelberg

The contributions about Katowice (Fig. 1, page 70), Essen and Gelsenkirchen show, for example,the re-design of single mining edifices. Buildings are adapted to new functions, presenting today the past mining history and culture (e.g. in form of museums like the Ruhr Museum, page 46) and hosting new economic activities (e.g. modern offices on the former Nordstern colliery, page 56; leisure facilities and shopping Beringen be-MINE, Fig. 2, page 26),hotspots for education or new cultural impulses like a music rehearsal centre in Gelsenkirchen or the site of "Fosse 9-9bis" in Oignies (Fig. 3, 4).

The examples of Belval, Kiruna and the Ruhr region address in addition the scale of neighbourhoods and landscapes. They exemplify the diversity of functional programming too (e.g. serving for housing, business, recreation and science), but highlight in particular the fruitful interplay of various planning and artistic disciplines. The former colliery Nordstern and the works settlement of Schüngelberg (Fig. 5, page 52), bringing together architecture, urban design, landscape architecture and art, are examples here.

All the local post-mining designs aim primarily to discover and re-increase local livability by proposing new and adapted uses, and to repair the environmental damages of mining when creating new attractive open spaces. In doing so, the projects often unfold transformative power in a mid- and longterm perspective: Many of them foster successfully the further economic, socio-cultural and ecological transformation of their proximities by giving new ideas, by creating new identities and positive awareness for the sites. The comparison of the examples reveal that many post-mining designs in Europe are not only big ad-hoc designs, but incremental projects, evolving over decades and drawing on the expertise of various actors and architects.

Ideas and innovations in designs are reformed over time and adapted to the present. The example of the colliery Hugo and Hassel (cf. paper of Axel Timpe,page 38) shows that nicely. The concept of "industrial nature", which Peter Latz developed in the 1990s for the landscape park Duisburg-Nord (page 60)with inspirations for post-mining park designs till today, turns here to the new idea of a "industrialised nature": The post-coal mining park becomes a park of re-growing fuels that thus responds to the longstanding need of increased livability and the current demand for resource conservation.

The strong reference to the history and heritage on site is another feature of European postmining designs. Anna Marijke Weber researches this reference in her paper Polyvalence: A Tool for Architectural Transformation (page 14). Comparing several post-mining designs in architecture, she sheds light on how designs deal with the material and immaterial, with authentic and associative legacies of the past mining sites. She reveals similarities and differences of designs and thus point to the tension between the specificity and innovation, on the one hand, and the principle ,imitation, transferability in design, on the other.Anna's contribution points explicitly to the value of comparison as strategy to generate new knowledge and to facilitate mutual learning. It may encourage further research that explores in more detail some of the aforementioned observations, for example,how and why post-mining designs unfold locally transformative power or not.

3.2 Reflecting the nexus of local designs and regional approaches to post-mining transformation

The contributions of Kuhn, Solonina et al.and Hajduga et al. in this issue recall the regional scale of post-mining transformation, when drawing attention to some of the biggest (post) mining regions in Europe. Apart from the scale, however,these contributions point also to the nexus, which links the local post-mining designs with the regional circumstances and approaches to cope with the complex post-mining transformations.

Ideally, both "levels of design" interplay in a positive, supportive manner. Regional approaches ideally embed, e.g. charge, inform or support at least financially and politically local post-mining designs and respective local initiatives for transformation.In turn - and as mentioned above - local postmining designs can unfold transformative power and impact on the development of their close proximities and the broader region, either as widely known icons (e.g. the Ruhr Museum and landscape park Duisburg-Nord) or as valuable and appreciated places of daily life.

One good example for the positive design of the local-regional nexus has been the International Building Exhibition (IBA) Emscher Park in 1989-1999 in Ruhr region of Germany. In the Ruhr region and in other examples (cf. Kuhn: IBA Fürst-Pückler Land, 2000-2010, page 66), the IBA proved to be a valuable strategic planning approach, which can stimulate and coordinate local post-mining designs on a regional level and encourage the commitment for the region of various actors in state, society and economy. The IBA approach can also help to design overall ideas and concepts for the spatial transformation of the region (cf. Approaches to Design Post-mining Transformations in European Regions, page 20).

Yet, the interdependence between regional and local post-mining designs does not work out well everywhere. In the case of the Ural Mountains(page 82), this nexus is missing. Local post-mining designs fall here back to Do-it-Yourself initiatives and the romanticism of wilderness and decay,since political, economic and planning support and interest are lacking at the regional and upper levels. The broader circumstances are thus decisive for the scope, pace and transformative impacts of post-mining designs at the local and regional level.In their contribution, Reicher and Neugebauer point out that neither strategic planning approaches like IBA at the regional level, nor local post-mining planning alone are sufficient to condition successful and sustainable post-mining transitions (page 20). Rather, the interplay of several factors and initiatives seems to be relevant in the European cases.

Some questions, which then and constantly comes up: To what extent do these European conclusions hold true in other global contexts? What are post-mining experiences as well as local and regional designs in China that could trigger further mutual learning? We hope that this thematic issue draws attention to the potential of mutual exchange on these questions.□