無拘無束的建筑:以親生物設計連接城市兒童早教中心與自然

薩拉·斯科特/Sarah Scott

龐凌波 譯/Translated by PANG Lingbo

在目前的早期教育中,兒童在戶外、在自然環境中玩耍是一種理想狀態,這是相當普遍的觀念。

兒童能夠接觸到大自然的重要性為很多基于發展心理學和“最佳實踐”游戲空間設計的研究所支持,它們證實了戶外環境比室內更健康、更刺激、更有趣[1-3]。全球范圍內戶外教育的增長亦是一種佐證(圖1)。不過,盡管戶外教育的現象增多,在城市中,并不總能夠接觸到自然的戶外環境。許多兒童在幼年時期大多待在城市的日托中心,并未真正接觸到自然[4]。氣候的變幻莫測只可能加劇這種情況。

建筑師需要為孩子們創造能最大程度與自然聯系的室內環境,同時在內部模擬自然的特性。通過多變的環境照明模擬一天內的光線變化,提供清新的空氣和可變的氣流,維持一定范圍的舒適溫度,以創造健康的室內環境。仰望天空的視野,非封閉的狀態,以及能夠同時滿足體育鍛煉和安靜休憩的條件,這些都是必需的,另外還應有視覺、聽覺、嗅覺和觸覺的持續而豐富的感官體驗。這就是親生物設計。

然而親生物設計不僅是關于這些基本的健康和使用需求的,而且事關人類本質上與其他生命體、與自然產生聯系的需求。

城市兒童中心需要保留一點原野感,“叢林化”自身的環境,不僅是為了容納兒童,而是創建一個微生態系統,令兒童、工作人員、家長能與之相連,形成一個不可分割的整體。

親生物設計為建筑增添了另一重維度,其中,建筑形式因光、影、日、月、空氣、風、重力對世界奧秘的變幻的揭示而變得富有生命力,兒童因此可以在自然中無拘無束地玩耍,無論是在室內還是室外。

諸如未來生活學院這樣的組織[5],致力于實現城市和人造場所中的自然環境,并將親生物設計分成幾個具體的可量化的部分。這意味著親生物設計可以像可持續設計那樣,納入現代建筑的結構工程中。可持續和親生物設計雖然并不相同,但他們特別兼容,甚至彼此共生。二者與兒童早期的生活環境十分相關。不過,在兒童早教中心采取親生物設計方法,建筑師需要特別考慮教育啟迪和兒童視角這兩方面。

1 空間

教育是一種社交活動。一所兒童中心須在微觀的兒童對兒童層面,以及宏觀的社區對社區層面促進這一社交特性。

為了成為一種社交場所,許多幼托中心都提供位于核心的公共空間,能夠被所有人使用。如果這個聚集空間有足夠的透明度,滿足周圍房間的視線、天空以及外部環境的視野,它將會更有效率(圖2、3)。因此,在幼托中心創造的關系是人與場所與氣候之間的。巨大的空間感可以在建筑層面實現,通過高聳的天花板和較小結構的對比,通過大量的空隙射入的自然光,通過吸引視線向上、向外乃至更遠,進入從窗外或開口外“借來的”空間。

在更微觀的層面,關系在空間和空間之間形成,例如地下空間的過渡區域,或是廊下空間。這些地方既非全然開放、曝光,也非完全閉塞,為疊加和混合提供了完美的中性領域(圖4、5)。

沒有哪個中心是完全沒有小房間的。兒童自然會被這些提供保護感和安全感的小空間所吸引。此外,小房間提供的庇護所可以減少注意力消耗,提高長時間精神投入的注意力和專注力(圖6、7)[6]。

1 悉尼百年紀念公園的游樂園,ASPECT景觀建筑事務所的設計為城市的兒童和成年人提供一個沉浸在自然綠洲中玩耍和冒險的機會/A playpark in Centennial Park, Sydney, designed by ASPECT Landscape Architects, offers city kids and adults alike an opportunity to immerse themselves in an oasis of nature-play and adventure(圖片來源/Source: The Ian Potter Children's WILD PLAY Garden)

2.3 中心餐廳區域連接著所有的游戲室/The central dining area connects all the playrooms(圖片來源/Sources: ToBeMe Early Childhood Centre, Fivedock,Scott and Ryland Architects)

4 悉尼圣文森特醫院臨時幼托中心的木質平臺以一種好玩和方便的方式連接了室內外/The external decks at St Vincent's Hospital temporary childcare centre in Sydney connects the indoors to the outdoors in a playful and accessible way

5 位于悉尼的劉易舍姆快樂學習早教中心周邊,以圍欄形成一片活躍的游樂區/The perimeter fence line at Laugh & Learn Lewisham Early Learning Centre in Sydney is utilised as an active play area(4.5 圖片來源/Sources: Scott and Ryland Architects)

2 環境健康與兒童感知

在改善早教中心老師和兒童的認知結果與健康方面,已有研究證實學校內部及其周邊的自然環境的價值[7]。改善空氣質量、熱環境與氣流的多變性、聲環境舒適度,將改進人的認知功能。足夠的自然光,以及確保人工照明復刻自然光線的變化與漫射光則同樣重要。這些環境品質對于人的健康的生理系統有著巨大的影響,也會影響人的認知功能、注意力、消化功能和睡眠模式。這一切對培養健康的兒童十分重要(圖8、9)。

人類具有與自然產生聯系的內在需求,這并非什么高深莫測的科學:我們傾向于呼吸新鮮空氣而非空調產生的空氣,傾向于自然光線而非人工照明,普遍偏好欣賞叢林或海洋的景象而非高樓大廈或高速公路,偏愛木材的氣味而非氯仿的。兒童尤其如此,他們特別依賴感官知覺來理解身邊的世界。

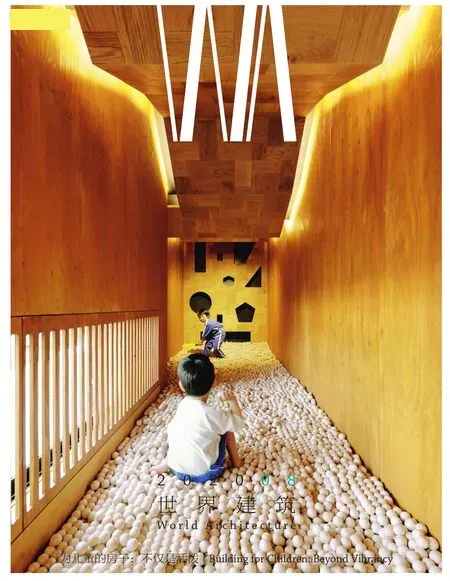

一個理想的兒童中心會采用多種多樣的自然材料肌理、圖案,并擁有對內和對外的自然視野,以及與自然系統的直接聯系。兒童中心的材料應當激發兒童對不規律感官刺激的需求:視界、聲音、觸感甚至是氣味,都是兒童能夠察覺到的幾個方面(圖10)。

顏色尤其重要。顏色對情緒和能量級的影響有著充分的記載。進化心理學和相關研究表明,人類對熱帶草原環境中的顏色有所偏好,特別是那些有益植物中具有的顏色。許多兒童中心會選擇平和的中性色彩方案,傳遞一個整潔、健康的場所的認知。一些聰明的以明亮色彩作為強調色的做法,則復刻了自然中對顏色的使用,以象征花朵和果實。太多顏色會引起過度的刺激,太少又會乏味,一個能營造溫暖氛圍的色域不僅能讓人的膚色看起來更漂亮,還能讓人感到更加愉悅(圖11、12)。

It is a fairly universal concept within current early learning pedagogy that children being outside,playing in a natural environment is ideal.

The importance of children having access to nature is supported by many studies, based on research stemming from developmental psychology and "best practice" play space design, that prove the outdoor environment is healthier, more stimulating and more fun than most indoor spaces[1-3]. The growth of outdoor schooling across the world is a testament to that (Fig. 1). But whilst outdoor schooling is a growing phenomenon it is not always possible in urban settings to access natural outdoor areas. There are many children that spend most of their early years in urban childcare centres without any real access to nature[4]. The vagaries of climate change will only make this situation more likely to increase.

Architects need to create indoor environments for children that maximise connection with nature and also simulate the qualities of nature internally. To create healthy indoor environments with variable ambient lighting that emulates the changing light of a day, provide plenty of fresh air and changeable airflow and a range of comfortable temperatures. There needs to be views of the sky, a lack of enclosure as well as opportunities for both physical challenges and quiet retreat, there needs to be sustained sensory enrichment, for sight, sound,smell and touch. This is biophilic design.

However biophilic design is not just about these basic health and performance requirements. It is also about the innate human need to connect with other living things, with nature.

Urban children's centres need to hold within them a little bit of wilderness, to "junglify" the setting, to house not just children but to create a micro-ecosystem that the children, staff and parents can connect with and feel a part off.

Biophilic design adds another dimension to architecture, where the built form is enlivened by the play of light, shade, the sun, the moon, air, wind and gravity in ways that reveal the mysteries of the world, allowing for unregimented play steeped in nature, whether inside or outside.

6.7 閱覽室包含了一個小型閱讀區/The library room incorporates a cubby reading area(圖片來源/Sources:ToBeMe Early Childhood Centre, Fivedock, Scott and Ryland Architects)

Organisations, such as the Living Future Institute[5], are devoted to achieving natural environments within an urban and manmade setting and have divided biophilic design into specific quantifiable components. This means it can now be incorporated within the structured programme of a modern building in the same measured way that sustainability is being incorporated. Sustainable and biophilic design are not the same thing but they are particularly compatible and can be symbiotic with each other. Both are particularly relevant within the early childhood setting. However, when applying biophilia to children's centres, architects need to specifically consider both the pedagogical implications and a child's perspective.

1 Spatial

Education is a social activity and a children's centre must facilitate this sociability, at both a micro level, child to child and at a macro level, from community to community.

To be a place of connections many centres provide a central communal space that can be utilised by all. This gathering space will be more effective if there is enough transparency to provide sight lines to both the surrounding rooms and also views of the sky and context beyond (Fig. 2, 3).Thus creating a relationship between the centre, it is people and the place and climate. A sense of great space can be achieved architecturally, with soaring lofty ceilings contrasted against smaller structures,by flooding open voids with natural light and by drawing the eye up, out and beyond, into "borrowed"space beyond windows or openings.

At a more micro level, relationships are made in the spacesimbetweensuch as the transition zone of the undercover area or the verandah. These spaces are neither fully open and exposed or closed away and offer a perfect neutral territory for overlapped and mingled play (Fig. 4, 5).

No centre is complete without cubbies. Children are naturally drawn to small cubby spaces that provide protection and containment. Additionally, the refuge that small cubby spaces provide can reduce attentional fatigue and enhance concentration and attention for prolonged mental engagement (Fig. 6, 7)[6].

2 Environmental Wellbeing and the Sensory Child

Research[7]has established the value of the natural environment within and around schools in improving outcomes and well being for both staff and children. Improving air quality, thermal & airflow variability, acoustic comfort improve cognitive function. Equally important is the provision of adequate natural lighting and ensuring that artificial lighting replicates natural lighting with dynamic and diffuse light. All these environmental qualities have a huge impact on a healthy human circadian system and can impact cognitive function, attention,digestion, and sleep patterns. All particularly critical to growing healthy children (Fig. 8, 9).

Humans have an innate desire to connect with nature, it is not rocket science; we would rather breathe fresh air than air that is conditioned, rather have natural light than artificial, generally prefer views of trees or the ocean to views of buildings or highways and prefer the smell of wood to that of chloroform. Children in particular, rely on their sensory perceptions to understand the world around them.

3 自然系統連接

反復和持續地與自然接觸不單是一種審美上的考慮。真正有價值地與自然接觸,需要從功能上與幼托中心的項目和教育融為一體。這樣做的基本原理在于一種信念,即設計的益處對人類健康和福祉有連鎖效應,因此將有助于同理心、自我意識、自我約束和自我恢復方面的發展。

戶外教育[9]16是一種提供與原始自然直接聯系的方式。在澳大利亞,現在有許多“叢林幼兒園”,也有許多幼托中心安排定期到戶外遠足。這些機構為兒童提供了機會,得以在建筑物邊界之外,自然的環境和系統中玩耍與探索,令他們直接感受到季節變化,自然中的種種關系,生命的循環,氣候和天氣特征,動物的習性,以及多重感官體驗。定期到某一相同地點旅行有助于實現時間導向下的與自然相連(圖13)。

另一種方式,理想情況下與前者協同,是將自然融入學校項目之中,例如在悉尼五碼頭公立學校的ToBeMe早教中心開始實施的永生花園規劃。能容納160名兒童的中心,建在一座工業區域中經過適應性改建的倉庫建筑中,旨在為團體或個人體驗提供一系列注重高質量和自然環境的活動。

既有的倉庫經過重建,加入了一個新的夾層,并在每層添加了室外娛樂區域,每一間娛樂室通過無障礙設施,始終具有直接和通暢的途經進入戶外景觀區(圖14)。

理解ToBeMe早教中心的理念對最終設計十分關鍵。項目包括兒童廚房、樂高屋、閱覽室、體育室,以及針對特定年齡的大游戲室和景觀化屋頂戶外游樂空間。

孩子們每日種植、施肥,除草、收獲,隨后在兒童廚房中,他們會備菜、烹飪,食用他們自己的收成。就像英迪拉·奈杜說的那樣,他們也許無法種植他們的所有食材,但他們可以食用所有他們的收成(圖15)[10]。

屋頂游樂區和花園被安排在一系列種有不同伴生植物的種植區周圍。一開始是一些橘子樹和草本植物,不過逐漸就發展成為了一個包羅萬象的蔬果名錄(圖16)。

早教中心的負責人法迪·艾爾吉塔尼的目標是引領孩子們和他一起,體驗如何與自然共存,而不是與自然對抗。永生花園特別強調建立互惠互利的關系[11]。花園并非孤立地長在那里,而是通過與孩子們的持續互動形成。所以孩子們可以在花園周圍玩耍,而花園亦不斷地發展和變化。通過教育兒童更多地了解植物,以及精心布置植物、道路、泥地以及其他基礎設施,來管理踩踏的實際問題和達成有節制的進出。這些要素用以建立自然的屏障,而無需持續對兒童行為進行糾正。

8.9 近期由斯科特與賴蘭建筑師事務所同克里斯·尤班克斯合作的布洛瑟姆預制組裝的日托中心,滿足并超越了澳大利亞現行規范的所有要求,提供了可持續、安全、健康、寬敞、光線充足且經過聲學優化并擁有一系列感官認知材料選擇的學習環境。3個分別為40、60、90名兒童設計的基礎模型,幾乎滿足了全部需求。一個可選附加項目的清單,包括了木質平臺和游樂設施、外部遮陽、內部游樂設施、美術室和餐廳的額外插座,各種固定裝置和配件等,拓展了其產品多功能性,是協同設計的一部分。該系統環境可持續,可配置為零排放。其材料具有高度可再生性與可循環使用性,顯著降低了每個游戲室的能耗和水資源消耗。它出自嚴格控制的工廠環境,提高了質量和運輸速度;現場安裝迅速,比一般施工進展速度快50%以上/Blossom prefabs, a recent collaboration between Scott and Ryland Architects and Chris Eubanks, has been designed to meet and exceed all the requirements of current Australian regulations, providing sustainable, safe, healthy,spacious, light-flooded, acoustically optimised learning environments with a range of sensory material options. Three base models for 40, 60 or 90 children covers most needs. A menu of optional extras including items such as decks and play structures, external shading,internal play structures, additional plug in art rooms and dining rooms as well as a variety of fixtures and fittings, extends the product's versatility, all as part of the coordinated design. The system is environmentally sustainable and can be configured to net zero emissions, it has a high renewable and recycled material content and significantly reduces energy and water costs per playroom.Manufactured entirely within controlled factory environment to increase quality and speed of delivery; the on-site installation process is fast, more than halving that of normal construction processes(圖片來源/Sources: Scott and Ryland Architects)

10 認知墻的其中一種/One of several sensory walls

11.12 游戲室內部的顏色設計是柔和平靜的/Playroom interior colour schemes are soft & calming(10-12 圖片來源/Sources: ToBeMe Early Childhood Centre, Fivedock, Scott and Ryland Architects)

13 野外玩耍,景觀設計師菲奧娜·羅伯設計了孩子們可以參與建造的互動景觀/Wild play, Fiona Robbe, Landscape Architect, designs interactive landscapes that the children can help to build(圖片來源/Source: Sarah Scott)

14 在輕工業場地中的綠植屋頂,將自然引入最需要它的地方/Green rooftop in a light industrial setting, bringing nature to where it is most needed

4 時間和運動

兒童熱衷于接受挑戰,他們不像成年人那樣從A到B直線移動。他們喜歡障礙訓練場、捉迷藏、迷宮、秘密小徑和多重選擇。兒童不只會行走,他們顛跑、跳躍、搖擺、跑步、蹦跳、漫游,甚至有時會逆向行走。他們會緊緊把握任何可以用來擴展運動范圍的機會,如保持平衡的墻壁、光滑的表面、秘密的隧道或窄小的門。

An ideal children's centre uses a variety of natural materials textures, patterns and has internal and external views onto nature and a direct connection with natural systems. The materiality of a centre should be designed to appeal to a child’s desire for non-rhythmic sensory stimuli: sight,sound, touch and even smell are aspects that a child will be aware of (Fig. 10).

Colour is particularly important. The impact of colour on mood and energy levels is very well documented. Evolutionary psychology and related research suggest that humans have a preference for colours found in savanna settings[6]12, particularly those colours found in healthy vegetation. Many childcare centres opt for a calming colour scheme of neutrals, which register perceptions of being a clean& healthy place to dwell. However, some judicious use of bright colours as accent colours replicate the use of colour in nature to be indicative or flowers and fruit. Too much colour can be overstimulating whilst too little can be sterile, a colour range that creates an ambient warmth is not only generally more flattering to peoples complexions but also makes people feel more cheerful (Fig. 11, 12)[8].

3 Natural Systems Connection

Repeated and sustained engagement with nature is not just an aesthetic consideration. To be truly valuable natural engagement needs to be functionally integrated within the children's centre programme and pedagogy. The rationale here lies within the belief that design benefits start cascading with real impacts to human health and wellbeing and therefore will support development in empathy,self-awareness, self-regulation and restoration.

Outdoor schooling[9]16is one way to provide a direct connection with wild nature. In Australia,there are now quite a few "Bushkinder" and many centres provide regular excursions to the great outdoors. These provide their children with the opportunity to play and explore natural cycles and systems beyond the boundary of the building,exposing them to seasonal patterns, relationships in nature and the cycles of life, climate and weather patterns, animal habits and multi-sensory experiences. A time-oriented connection with nature is facilitated by regular trips to the same location(Fig. 13).

Another way, ideally in tandem, is to incorporate exposure to nature within the school programme, such as at the ToBeMe centre in Fivedock, Sydney, where a permaculture programme has been instigated. The 160 child centre was created within an adapted warehouse building in an industrial setting. The aim is to provide a range of activity focused on high quality and natural environments for both group and personal experiences.

The existing warehouse was reworked to incorporate a new mezzanine and outdoor play areas on each level, every playroom having direct and fluid access to landscaped outdoor areas with disabled access throughout (Fig. 14).

Understanding the ToBeMe Early Learning's vision was critical to the final design. There is a kids kitchen, lego room, library and gymnasium as well as large age-specific playrooms and landscaped rooftop outdoor play space.

The children are involved daily in planting and nurturing the plants, weeding and harvesting and then in the kid's kitchen, they are involved in the preparation, cooking and eating of their yield. As Indira Naidoo puts it, they may not be able to grow everything they eat but they can eat everything they grow (Fig. 15)[10].

15 一系列兒童園藝和玩耍的照片/A range of images of children gardening and playing(14.15 圖片來源/Source: ToBeMe Early Childhood Centre,Fivedock, Scott and Ryland Architects)

The rooftop play area and garden has been planned around a series of growing zones for different companion plants. It started with orange trees and herbs but has evolved into a comprehensive list of fruit and vegetables (Fig. 16).

The Director, Fady Elghitany's goal was to take the children on a journey with him on how to live with nature, not against it. Permaculture strongly emphasises building mutually beneficial and symbiotic relationships[11].The garden is not generated in isolation, but through continuous and reciprocal interaction with the children. So the children are allowed to play in and around the gardens with the gardens being continually evolving and changing. The practical issue of trampling and controlled access is managed through educating the children about being more aware of the plants and also by the careful placement of plants, pathways,earthworks and other infrastructure. These are used to create natural barriers without the need for constant input in corrective management.

在意大利雷焦艾米利亞地區,老師們表示,他們并不會將建筑環境看作客體而是主體,因為它會與孩子們互動,不論是以圍合還是挑戰的方式。

有目的地將建筑環境設計為可互動的、隨時間變化的,而不是靜態的,將創造另一重類似自然環境的刺激,它應當是非線性的、充滿選擇的(圖17、18)。

在實踐中,這意味著提供各種各樣不同的選擇,培養想象力,使孩子們能夠在整個建筑中,從安全的小尺度空間,到帶有冒險性的較大的公共區域自由移動,通過細節帶來復雜性和愉悅感,建立起與自然世界的強可達性連接,以及起伏的窗對有著天空、樹木以及大量自然光線的景致的室內外連接。

奇威爾兒童與家庭中心由斯科特與賴蘭建筑事務所與莫里森-布雷滕巴赫建筑事務所合作設計。該中心是在與塔斯馬尼亞政府和當地投資者的詳細咨詢與匯報過程中逐漸發展出來的。該建筑創造了一種為兒童的互動游戲結構,“游戲脊柱”成為了建筑的核心,在建筑內以一系列橋和攀爬結構的形式自建筑中心向下延伸。這為孩子們提供了另一條自由且具有創造性的穿越建筑的路徑(圖19)。

一棟建筑同樣可以被動地提供隨時間變化的物理形態,例如光影在它形式上的變化,或是材料的銹蝕光澤。

為了真正地模擬自然,一棟建筑不應是靜態的。盡管我們并不能令墻體移動,但我們能夠制造從游戲室到其他活動區域的開敞的視線,甚至僅是驚鴻一瞥;我們還能夠通過恰當的放置好聞的香草和定期的蛋糕烘焙來滲透空間。建筑層面,光影的變幻非常關鍵(圖20):

“當沉浸在自然中時,我們會不斷地感受到隨機的刺激:鳥兒鳴叫、樹葉的沙沙作響、空氣中淡淡的花香。這些體驗分散我們的注意力,令我們愉悅、放松,使我們在專注的任務中得以短暫休息,與此同時保持著一定程度的警覺和聯系,就像旋轉的樹葉暗示著風暴降臨,或是日光顏色和投影的微妙變化暗示著時光的流逝一樣。”[6]13

16 永生花園規劃/Permaculture Plan

17.18 使用非線性規律刺激感官:樹枝!/Use of non-linear rhythmic stimuli: tree branches!(16-18 圖片來源/Sources: ToBeMe Early Childhood Centre, Fivedock, Scott and Ryland Architects)

5 復雜性與秩序

自然環境可通過秩序或模式的疊加而豐富,也可以通過關系來豐富。

親生物設計理想中的建筑的和諧與美,通過利用自然和自然中出現的秩序,諸如黃金分割的分形比率,明確建筑的層級關系,或采用重復的有韻律的圖案,對自然形式如貝殼或葉子的模仿,或偶爾僅包含一些出乎意料的東西(圖21、22)。

東溪兒童保育中心,由斯科特與賴蘭建筑事務所受澳大利亞輝盛地產委托設計,是一座風格化的村莊,簡單好玩的幾何形態使其成為對社區中的兒童而言可以識別的場所。在澳大利亞,階梯坡屋頂形式可與現有的街道景觀結合,同時在中間圍合并保護出一片室外游樂區免受道路的影響。戶外的游樂區朝北,并使所有游樂室直接朝向戶外游樂空間,以最大化地利用自然光線。橢圓形戶外游樂區的強有力的幾何形式,使其成為該中心的主要特征。附加的景觀“綠廊”位于娛樂室之間,兒童可以進入,這為兒童的健康增添了可持續、親生命且有趣的和諧環境。

19 孩子們可以移動穿越結構核心,將之作為一種游戲架構,而大人則可在地面上進行照看/The children can move through the structural spine using it as a play structure while the adults can supervise from the floor plane(圖片來源/Sources: Chigwell Child & Family Centre designed by Scott and Ryland Architects, in collaboration with Morrison Breytenbach Architects)

4 Time and Movement

Children love a challenge, they do not move in straight lines from A to B as adults do, they like obstacle courses and hide and seek, mazes, secret ways and myriad options. Children do not just walk,they hop, skip, shimmy along their bottoms, run,jump and meander, sometimes backwards. Any prop that can be used to extend the scope of movement is seized upon; a wall for balancing, a slippery surface,a secret tunnel or a tiny door[9]65.

At Reggio Emilia, Italy, the teachers stated that they did not see the built environment as an object but as a subject, because it interacts with the children,whether it encloses them or it challenges them.

Purposely designing the built environment to be interactive and changeable over time, rather than static, creates yet another layer of stimuli that mimics the natural environment, which is very rarely linear or without choice (Fig. 17, 18).

In practical terms, this means providing a variety of different options that fosters imagination and allows for children's free movement throughout the building, from the security of small cubby scaled spaces to the challenge of larger communal areas with the scope for adventure. Providing complexity and delight in the detail and a strong accessible connection with the natural world, connecting views in and out, waving windows, views of the sky and trees and lots of natural light.

The Chigwell Child & Family Centre was designed by Scott and Ryland Architects, in collaboration with Morrison Breytenbach Architects.The Chigwell Centre was developed out of a detailed consultation and briefing process with the Tasmanian Government and local stakeholders. The building creates an interactive play structure for the children. The "playspine" becomes the heart of the building running down the centre of the building as a series of bridges and climbing frames within the building's structure. This creates an alternative route for children to move through the building in a free and creative manner (Fig. 19).

A building can also passively provide physical evidence of changes over time such as the play of light and shadow on its form or the ageing patina of materials.

To truly mimic nature a building should not be static. Whilst we cannot make the walls move, we can allow for open sightlines or even just glimpses,from the playrooms to other areas of activity, we can allow for judicious placement of nice smelling herbs and the regular baking of cakes to permeate space. Architecturally, the play of light and shadow is critical (Fig. 20):

When immersed in nature, we continually experience instances of non-rhythmic stimuli: birds chirping, leaves rustling, the faint floral aroma in the air. These experiences distract, delight, and relax us to provide momentary breaks from focused tasks, while maintaining a level of awareness and connectedness, much like the whirling of leaves that hint of an approaching storm or the subtle progression in daylight colour and shadow casting indicating the passage of time [6]13.

5 Complexity & Order

Natural setting is enriched by layers of order and pattern and also by association.

Biophilic ideals of architectural harmony and beauty reflect nature by utilising fractal ratios that occur within nature and naturally occurring orders such as the golden mean, clear architectural hierarchies, patterns of repetition,rhythm and simulations of natural forms such as shells or leaves and occasionally, just including the unexpected (Fig. 21, 22).

親生物設計通過改善室內空氣質量、營造學習空間內自然降溫的微氣候,以及最優化交叉通風和自然光線,形成使用者和自然之間的關系。機械空調被最大程度地削弱。貯存的灰水將用來澆灌植物。安裝朝北向的太陽能光伏板用于降低能量消耗和運行成本。使用澳大利亞認證的硬木并非只為了審美,木材具有耐久性,可以回收,并在未來有目的地進行再利用。

與園丁景觀公司合作設計的戶外游樂區,是兒童主要的學習對象。其中,各種不同的野外冒險游樂花園,攀爬架,不同種類的植被如成熟的樹木,空中花園,以及具有不同肌理、氣味和顏色的低感官花園,使得孩子們能夠通過視覺、聽覺、嗅覺和觸覺進行學習。每個游戲室在布局上都設計得很靈活,有大教堂式的天頂、大面積的落地窗、寬敞可達的潮濕區域和儲藏室。設計旨在將這一保育中心建成一座設施遠超規范要求的模范中心。

以自然環境和互動過程為重點設計兒童早教中心的好處怎么強調都不過分。它將戶外的優勢,如自然光、空氣、變化的感官刺激,與室內的優勢相結合;它既實用又可監管,不會受極端天氣影響,這將確保我們給予下一代茁壯成長所需的身心健康。

20 由帶有圖案的隔音織物簾幕在墻面上形成的陰影/Shadows on the wall from patterned acoustic fabric screen(圖片來源/Source: ToBeMe Early Childhood Centre, Fivedock, Scott and Ryland Architects)

21 正在進行的項目,將設計為沉浸式的親生物兒童中心/A work in progress, designed to be an immersive biophilic centre(圖片來源/Sources: Eastern Creek Childhood Centre, Scott and Ryland Architects)

a-平面展示綠廊和中心的景觀化游樂區/Floorplan showing green corridors and central landscaped play area

b-景觀平面詳圖/Detailed landscape plan

Eastern Creek Childcare Centre, designed by Scott and Ryland Architects for Frasers Property Australia is a stylised village with simple playful geometries that identify the centre as a place for children within the community. Domestic scaled pitched roof forms are arranged to align to the existing streetscape whilst enclosing and protecting the central outdoor play area from the road. The outdoor play area faces due north to maximise natural light with all the playrooms facing directly onto the outdoor play. The strong geometric form of the oval outdoor play area helps define it as the main feature of the centre. Additional landscaped"green corridors" are located between the playrooms and are an accessible feature adding a sustained biophilic, playful and harmonious setting for children's wellbeing.

The biophilic design fosters a relationship between users and nature with improved indoor air quality, natural cooling microclimates within learning spaces, maximised cross-ventilation and natural lighting. Mechanical air conditioning is minimised. Greywater storage will be used for watering plants and north-facing solar panels are implemented to reduce energy consumption and operational costs. The use of certified Australian hardwood is not just aesthetic. Timber is durable and can be recycled and reused for future purposes.

The outdoor play area, designed in collaboration with "The Gardenmakers" is a major learning asset with a variety of different wild adventure play gardens, climbing structures and different types of vegetation such as mature trees, hanging gardens and low sensory gardens with variable textures,scents and colour enabling children to learn through their senses of sight, sound, smell and touch. Each playroom is designed to be flexible in layout, with large cathedral ceilings, big picture windows and generous accessible wet areas and storage. This centre aims to be an exemplar centre with facilities above and beyond the code requirement.

The benefits of designing children's centres and programmes with a focus on natural environments and processes cannot be overstated. Combining the advantages of the outdoors with its natural light, air,changeable stimuli and interconnectivity with the advantages of indoor areas; practical, supervisable and protected from the more extreme weather conditions, will ensure that we are giving the next generation the physical and mental health they need to thrive in life.

22 正在進行的項目,將設計為沉浸式的親生命兒童中心/A work in progress, designed to be an immersive biophilic centre(圖片來源/Sources: Eastern Creek Childhood Centre, Scott and Ryland Architects)

a-南立面大落地窗與植物盆栽結合/South elevation large picture windows with integrated planters

b-鳥瞰/Birds' eye view

c-游戲室之間的景觀化分隔空間局部平面/Detail plan of landscaped breakaway space between playrooms

d-游戲室內草圖/Interior sketch of playroom

e-設計提案中的綠廊景觀樣例/Example of proposed green corridor landscaping