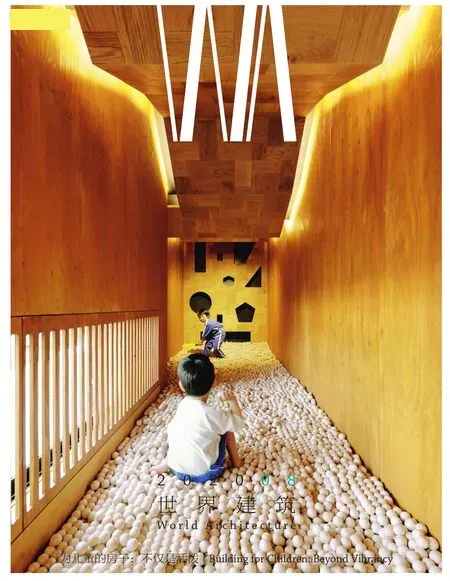

為孩子營造美好城市

延斯·阿茲/Jens Aerts

天妮 譯/Translated by TIAN Ni

毫無疑問,21世紀是城市化的世紀。與此同時,人們越來越認識到,城市化進程不但沒有使與經濟發展相關的個體生態足跡最小化,反而加劇了這種增長。由于不可持續的城市化進程,地球正處于崩塌的邊緣。此外,“人口增長是主要問題,計劃生育是拯救我們所居住星球的一劑良方”,這一觀點的全球語境正在縮小。在城市化的世界背景和老齡化社會的實情之下,呼吁建設兒童友好型的城市很有難度。2018年筆者為聯合國兒童基金會撰寫了《兒童友好型城市規劃手冊》(下文簡稱《手冊》)[1],這篇文章是基于手冊中提出的原則、概念和建議發展策略所撰寫的。同時,以在中國寧波建設的兒童友好社區為例,闡釋了如何在一個真實、立足實際的情境中對《手冊》的理論進行驗證(圖1)。

為什么為兒童規劃城市很重要?

《手冊》的第一章解釋了為什么我們應該為兒童規劃城市,且將兒童置于首位。 對主要城市的環境分析表明,城市化并不一定能為兒童帶來可持續的城市環境。首先,全球貧民窟居民中,約有3億是兒童,他們遭受著多重剝奪,生活中沒有話語權,甚至被土地、住房和服務等權益排除在外[2]。第二,在對規劃層面缺乏投資的情況下,城市擴張大多是碎片化的,集中度有限,缺乏公共空間,城市形態不緊湊。對于兒童來說,這意味著不健康和不安全的環境,步行和玩耍的選擇有限,與社會網絡、服務和地方經濟的連接度也有限。第三,現有的城市地區在能源消耗和CO2排放方面占比較高,從而給環境和城市本身帶來壓力。為更好地利用城市資源系統,就需要在能源效率及構建可持續的生活方式層面進行創新。由于兒童的行為是由其與城市環境的持續互動所塑造的,因此兒童參與建設可持續城市將成為城市和地球未來的決定因素。

《手冊》出版以來,舉辦了一些引發關注的活動,這些活動有力地印證了為什么兒童有必要成為關于公平、可持續性和適應力等問題所討論的中心。在過去的兩年里,兒童和年輕人展示了其獨特的力量,呼吁成年人負起責任,按照氣候科學倡導我們的去做。氣候變化是首要問題,需要盡一切努力扭轉局面。通過系統地關注兒童,城市規劃者進行了更清晰地分析并獲得了更多佐證,從而向決策者和利益相關方闡明,城市規劃在實現可持續發展目標(SDGs)中所發揮的核心作用。兒童是將要逆轉老齡化城市的未來一代,因此,他們需要在孩提時期保持健康、感到安全并獲得智慧和自信。與兒童一起規劃社區是從“診斷”到“共同生產”、是“協作學習”和“實踐過程”的一部分。為兒童規劃且有兒童參與營造的城市不僅以未來為導向,還涉及到“公平”。COVID-19疫情非常清楚地表明,成年人已經采取的各項舉措所帶來的后果是由兒童來承擔的。雖然老人在疫情中所面臨的風險最大,但避難措施對于兒童的連帶影響最大,他們失去了受教育、玩耍和體育活動的機會。只有所有人都健康,城市才能具有韌性和可持續性。兒童所面臨的現實狀況為定制基于公平的規劃和投資決策提供了最佳視角(圖2)。

我們要規劃什么?如何為兒童規劃城市?

《手冊》以城市規劃的三大潛在優勢為基礎,闡述了應如何規劃兒童應答型城市。在9個技術章節中,每一章都分別側重于城市環境的一個組成部分:住房、服務設施、公共空間、交通、用水、食物、廢物循環、能源和數據網絡:

(1)為兒童和社區規劃、設計和管理不同尺度城市空間的工具。這意味著,空間不僅僅是簡單作為游戲場地,而應從定性和定量的角度,提供各種可供兒童使用、享受的城市空間和基礎設施。因此,距離和安全可達性是關鍵條件。然而,盡管有著豐富的開放空間,大多數城市卻并沒有為兒童提供能夠玩耍、社交、培養自信、以一種獨立且安全的方式探索城市的近身空間。城市中兒童所在的房屋往往被停車場、擁擠的街道及污濁的空氣和土壤所包圍。

(2)為加強兒童和其他利益相關方參與地方事務的能力而設計規劃過程的策略。這意味著從數據收集和分析開始,一直到設計和實施的全過程,都需要根據孩子的年齡,運用不同的技術,傾聽兒童并與兒童一起工作。孩子們非常清楚其周邊社區面臨著怎樣的風險。對科學技術手段運用嫻熟的青少年甚至還擁有全市乃至全球視野的知識儲備。然而,卻幾乎沒有人詢問兒童的意見,抑或當兒童發出聲音想要參與時我們給予了消極的反饋。這導致了一種象征性的參與過程[3]。

(3)通過數據制定基于依據的、以人為本的決策方法。通過監測評估“如何營造建筑環境”“土地使用”和“空間分布如何影響兒童福祉”的數據指標,將其數據平臺納入政策制定和城市規劃體系,城市將獲得一定的公信力,并成為兒童應答型城市規劃方面知識交流和能力建設的關鍵角色[4]。然而,數據往往不是依年齡劃分的,大多數專業人士并沒有收集或儲備關乎兒童的數據和知識。調查詢問成年人的意見并收集有關成年人行為的數據使得我們對兒童在特定環境下的行為知之甚少(圖3)。

1 中文版《兒童友好型城市規劃手冊》封面/Front cover publication

2 兒童參與和公民意識/Children's participation and citizenship(1.2 圖片版權/Copyright: UNICEF)

3 城市規劃工具概覽/Three types of urban planning tools towards child-responsiveness(圖片版權/Copyright:UNICEF)

9個技術章節都分別強調了5個有利于兒童的領域:健康、安全、公民權、環境可持續發展和繁榮。將城市規劃工具劃分為3個層次,既可以著眼于短期結果,又可以為長期的增量變化奠定基礎。腳踏石研究法還具有激勵作用:基于各個城市的能力和資源,他們都可以采取措施以更加趨近于兒童應答型城市的構建。《十項兒童權利與城市規劃原則》鼓勵每個利益相關方迅速評估有哪些措施可以承擔責任并改善兒童的處境,同時尊重城市的能力和資源。

城市將兒童計劃納入主流

在呼吁各城市踐行兒童應答型城市規劃原則之余,《手冊》還附帶了一項傳播策略,以激發地方參與并在具體的城市環境中加以應用。免費的線上手冊及專業媒體的關注催生了各種活動,如交流討論、工作坊及與地方機構的聯合培養等。在《手冊》出版的最初18個月里,線上注冊下載量超過3500次,向合作伙伴分發的印刷版逾500份。《手冊》由中國城市規劃學會協助翻譯,于2019年10月啟用。

筆者與學術伙伴、專業團隊、地方政府及來自各技術領域的非政府組織的專家一起進行了培訓,在17個國家舉辦了研討會和工作坊,面對面培養了約1400名專業人員。菲律賓、巴拉圭和南非的聯合國兒童基金會與國家學術合作伙伴共同設立了指導員培養計劃,使得70多名城市規劃指導員具有推動兒童權利方面的相關資質。隨后,這些導師將參與兒童權利和城市規劃方面的進一步培訓,課程涵蓋學術基礎和高級專業水平兩個級別。我了解到,許多活動的參與者也隸屬于涉及城市規劃及政策的其他重要機構,這次培訓為其提供了一個思考如何將兒童權利與其所在機構相融合的契機。由于該培訓還包括一個學校特定情景之下的模擬環節,參與者能夠隨時練習如何從孩子的角度分析當地情況,并優化設計。有時,這些設計建議已經轉化翻譯完畢,并準備根據現有資源予以實施。長遠來看,該培訓也是可以影響地方和國家公共機構的杠桿,從而使任何城市的規劃教育課程體系中都能納入兒童的觀點,對目前城市政策、城市發展的總體規劃及設計準則做出堅實地評估和改進(圖4、5)。

中國寧波的社區示范項目

在寧波市為期一周的國際青年規劃師工作坊中, 因為兒童的有效參與,《手冊》的各項原則得到了全面執行。寧波工作坊由國際城市和區域規劃師學會(ISOCARP)發起。該學會此前協助起草并發放了兒童應答型城市規劃《手冊》,共同促進繁榮且公平的城市,使兒童生活在健康、安全、包容、綠色、繁榮的社區。工作坊由中國城市規劃學會(UPSC)主辦,寧波市自然資源和規劃局(NBNRP)、寧波市規劃設計研究院(NBPI)承辦,已于2019年8月26-30日舉行1)。

寧波是一個經濟繁榮的宜居城市,曾9次獲評為“中國最幸福城市”。然而,“幸福感”是否能夠轉化給童年,這依然是個問題。兒童的日常生活在社區內發生,因此,工作坊旨在對示范社區進行升級,該社區可作為其他類似社區項目的升級樣板。明東社區1996年建于一個由4條主干道劃分出的矩形區域內。占地17.59hm2,建筑面積120,000m2。社區共有56棟住宅樓,住戶170家,居民550人。朝暉實驗小學位于小區的東北角,是全市最大的農民工子弟小學,也兼具文化中心和繼續教育培訓學校的功能。此外還有社區公園、一所中學及一個體育中心。附近的購物中心、公園和超市等設施為社區提供了良好的服務。選擇明東作為工作坊示范區的主要原因,是因為社區內中低收入家庭和外來務工人員的子女較多。盡管社區為兒童提供了基本設施,但仍亟需對其進行詳細評估,然后做出改善,從而提高兒童的滿意度。此外,該社區已經參與了一項轉型計劃,可以通過工作坊將孩子們的觀點加以補充。這一因素使案例研究具有較強的挑戰性及相關性(圖6)。

來自寧波、中國其他城市和其他國家的6名導師及18名青年規劃專業人士參加了此次工作坊。他們和來自當地4所學校的15名6~12歲兒童一起,共同分析并提出了一個明東社區的改造方案。作為研究方法的一部分,兒童積極地參與了工作坊從研究到設想再到擬訂設計建議的每一個階段。他們為闡明當前形勢、明確問題和挑戰并應對社區狀況做出了顯著貢獻。為了能根據年齡了解兒童的需求和心愿,孩子們大致分為3類(0~6歲,6~12歲和12~18歲)。

工作坊以“兒童之家”的主題為基礎,探討了有關可持續城市發展和兒童權利的3個問題:

(1)最年輕的一代如何感知并生活在這座城市?

通過問卷調查和諸如短途散步等各種非正式活動,孩子們講解了自己與場地的關系,展示了日常游戲的空間,并對在使用這些空間時是否遇到了問題等予以明確。他們還在地圖上標出了每天在社區中最常走的路線。這一人類學實踐也暴露了盡管開放空間可用,但缺乏連接途徑的問題和擔憂。例如,社區街道全部被用作停車場、老年人能夠很好地使用公園的特定區域,但該區域的設計對兒童沒有吸引力,也沒有促進代際互動。兒童還指出,由于課外補習、興趣班或額外的家庭作業使得他們幾乎沒有時間在外面玩耍(圖7)。

(2)對明東這個兒童友好社區有何展望?

在為明東構想兒童友好空間時,我們有意強調了游戲對認知發展、心理健康和身體技能等方面的益處。當兒童在游樂場玩耍時注重組織“小組討論”。在為當地兒童實現夢想和愿望時,為其設想一個有親切感、安全、有創意的社區空間,這對于規劃者也是一個重溫自身童年的契機。我們了解到兒童從很小就有繁忙的日程安排,所以顯然,游戲空間應該與散點狀的公共空間網絡整合在一起,讓兒童在外出時使用,或者從居住地便捷可達(圖8)。

(3)如何采取行動?

為使兒童能夠更經常在戶外玩耍,為其安全玩耍創造條件就十分必要。目前,由于父母認為其所在的社區不夠安全,所以只能長時間地照看孩子。因此,社區應該重新組織內部的交通流線,營造“少車區”或“無車區”。這個安全路線或“絲帶”系統可以連接所有重要的兒童設施及場所。絲帶系統需要遵循的高品質設計要求有:(i)以不間斷的路線為目標,這使得安全的交通路口及優先考慮處于危險交通狀況中的兒童成為可能; (ii) 促進隨心所欲的玩耍,玩耍不應只局限于指定的區域,而應可以沿著路線進行;(iii)為兒童加強可識別性,這意味著需要明確標記絲帶系統,如鋪設彩色路面等(圖9-11)。

中國在兒童應答型城市規劃方面的潛在領導力

中國是一個有著悠久城市歷史的國家,是發展文化、經濟及福利設施的中樞核心。盡管中國的城市規劃實踐仍展現出快速規劃、大規模規劃的獨特能力,但大多數當代城市發展規劃都只關注基礎設施,忽略了以人為尺度。如:功能單一的高層居住區、以汽車為導向的交通基礎設施、大型建筑街區及步行性不佳的寬闊街道。在空氣污染、社交隔離和物理邊界普遍存在的新的城市環境中,我們為兒童預設了一種非健康的情景。毫無疑問,他們將遭受到心肺疾病、肥胖和糖尿病、壓力和精神疾病的更多困擾。此外,對死亡患者的研究表明,如果沒有良好的健康狀況,像COVID-19這樣的病毒將具有致命的影響。

縱觀進行中的中國城市化圖景,特別是雄心勃勃的“一帶一路”倡議,這是一個反思先前城市規劃的缺陷并以更加人性化的方式塑造我們城市的新機遇。贊美兒童、關注民生健康、世世代代共享愛與關懷,這正是尋求新的途徑以發展更可持續的城市化模式的動力。位于寧波的試點項目可以引領其他城市采取兒童應答式的城市規劃實踐,并建立一個繁榮且公平的城市網絡,讓兒童生活在健康、安全、包容、綠色和繁榮的社區。

The XXI century is urban without any doubt. At the same time there is a growing acknowledgement that our planet is on the verge to collapse, due to unsustainable urbanisation that, instead of minimising, is amplifying the growth of our individual ecological footprint correlated with economic development. Also, there is a narrowing global discourse that the demographic growth is the major issue and that family planning is the silver bullet to save our urban planet. Within this context of an urbanising world and a factually ageing society it is difficult to call for child-friendly cities. This article goes against the stream and builds upon the principles, concepts and recommendations developed in theHandbook on Child-Responsive Urban Planningthat I authored for the United Nation's Children Emergency Fund in 2018[1]. It also illustrates how the theory of the book has been tested in a real,contextualised workshop to build a child friendly neighbourhood in the Chinese city of Ningbo (Fig. 1).

Why Planning Cities for Children Is Important?

In a first of three chapters the Handbook explains why we should plan cities for children, and foremost with children. Analysis of the main urban contexts shows that urbanisation does not necessarily induce sustainable urban environments for children. Firstly,an estimated 300 million of the global population of slum dwellers are children, who suffer from multiple deprivations, live without a voice and have no access to land, housing and services[2]. Secondly, without investment in planning, urban expansion mostly occurs in a fragmented way, with limited centrality,a lack of public space and no compactness in urban form. For children, it means unhealthy and unsafe environments, limited options for walking and playing, limited connectivity to social networks,services and local economy. Thirdly, existing urban areas are responsible for proportionally higher energy consumption and CO2emissions, thereby putting stress on the environment and the cities themselves.Improved use of urban resource systems necessitates innovation in terms of energy efficiency, but also in forging sustainable lifestyles. As children's behaviour is molded by their ongoing interaction with the urban environment, children's participation in shaping sustainable cities will be a determinant for the future of our cities and for our planet.

Since its publication, some striking events have taken place that support even more why children need to be central to any discussion on equity, sustainability and resilience. Last two years,children and young people have shown their unique strength to call adults to be responsible and to act according to what climate science imposes us to do.Climate change is the number one emergency and all efforts are needed to bend the curb. By focusing on children systematically, urban planners will conduct sharper analyses and gain more comfort to explain to decision makers and stakeholders that urban planning plays a central role in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Children are the future generation that will have to run the ageing city of tomorrow, so they need to be healthy, feel safe and have gained intelligence and confidence during their urban childhood. Planning neighbourhoods with children is part of this collaborative learning and doing process, from diagnostics to coproduction. Cities planned for and with children are not only future-oriented, they also deal with equity.The COVID-19 pandemic has shown very clearly how children carry the burden of the measures that adults have put into place. Although almost all older people were at risk, children suffered most the consequences of the shelter-in-place measures, depriving children from education, play and physical activity. Cities can only be resilient and sustainable if they are healthy for all, and children's specific situation gives the best perspective to make equity-based planning and investment decisions (Fig. 2).

What and How Can We Plan Cities for Children?

In nine technical chapters - each one focusing on an urban environment component: housing, amenities,public space, mobility, water, food, waste, energy and data networks - the handbook illustrates how cities can be planned to be child-responsive, building on three potential strengths of urban planning:

(1) To improve instruments to plan, design and manage urban space on different scales for children and the community. This means place is not simply a matter of providing playgrounds, but about providing all sorts of urban space and infrastructure that is accessible and enjoyable by children, from a qualitative and quantitative perspective. Proximity and safe accessibility are hereby key conditions. Yet,despite the abundance of open space, most cities do not offer close-by space for children to play, meet and develop confidence to explore the city in an independent and safe way. Children's houses in cities are completely surrounded by parking lots, heavy traffic streets and mostly polluted air and soils.

(2) To enhance design processes that strengthen local capacities of children and other stakeholders.This means using various techniques, according to their age, to listen and work with children, from the moment of data collection and analysis, through the design and production process. Children have time and they know very well what is at stake in their close-by neighbourhood. Tech savvy adolescent also have city-wide and global knowledge. Yet, hardly ever children's opinion is solicited, resulting in tokenistic participatory processes, or in negative comments when they raise their voices[3].

(3) To invest in evidence-based and peoplecentred decision-making through data. With monitoring and evaluation of data and indicators on how the built environment, land use and spatial distribution affects children's well-being, cities will gain credibility to integrate their data platforms into the design of policy and urban programming and become key players in knowledge exchange and capacity building on child-responsive planning of cities[4]. Yet, mostly professionals forget to collect or use data and knowledge of children.Surveys ask opinions of adults and collect data on their behaviours. Little is known about children's behaviours in specific contexts. Data is often not disaggregated by age (Fig. 3).

4 菲律賓兒童基金會和菲律賓大學城市和區域規劃學院聯合培養兒童應答型城市規劃碩士/Co-hort master trainers on child-responsive urban planning, with UNICEF Philippines and University of Philippines - School of Urban and Regional Planning(UP-SURP) (圖片版權/Copyright: 延斯·阿茲/Jens Aerts)

5 基于巴拉圭兒童基金會和國家道路安全局聯合培養項目中提出的建議改善校園環境/Improvement of school environment, based on recommendations produced during the training with UNICEF Paraguay and the National Agency for Road Safety(圖片版權/Copyright: UNICEF Paraguay)

Every chapter highlights what are the benefits for children in five benefit areas: health, safety,citizenship, environmental sustainability and prosperity. By organising urban planning tools on three levels of complexity, planning can both have a focus on short-term results whilst laying the foundation for incremental change for the longer-term. The steppingstone approach also has a motivational aspect: every city, depending on its capacities and resources, can take a step to become more child-responsive. A checklist of10 Children's Rights and Urban Planning Principlesencourages every stakeholder to quickly evaluate what can be done to take up responsibilities and improve the situation of children, respecting capacities and resources.

Mainstreaming Capacity of Cities to Plan for Children

The handbook and its call to cities to commit to child-responsive urban planning principles also came with a dissemination strategy, so to spur local interest and application in specific urban contexts.A free on-line version and uptake in professional media generated various activities such as dialogues,debates, workshops and trainings with local partners. In the course of the 18 months since its original publication, more than 3500 downloads were registered, and 500 hard copies were sent out to partners. The Urban Planning Society of China facilitated the translation of the handbook in Chinese, that was launched in October 2019.

In collaboration with academic partners,professional groups and local public authorities,experts from various technical NGOs and myself conducted trainings, seminars and workshops in 17 countries, reaching approximately 1400 professionals directly. UNICEF Philippines, Paraguay and South-Africa set up a training of trainers programme with national academic partners, so to capacitate more than 70 urban planning tutors on child rights.Subsequently, these tutors will set up further courses and trainings on child rights and urban planning,both on an academic basic level and an advanced professional level. Knowing that many participants are also affiliated with key institutions that are involved in day to day urban planning and policy, the training gave them an opportunity to think how to mainstream a child right approach within their organisation. As the programme also included a simulation project in a specific context of a school environment, participants were able to practice instantly how to analyse a local situation from a child perspective, and to come up with design improvements. In some cases, these design proposals have been translated further and are ready to be implemented, depending on available resources.On the longer term, the training is also a lever to influence local and national public authorities to include the children's lens in any future urban planning education curriculum, as well to consistently assess and improve current urban policies, masterplans for urban development and design guidelines (Fig. 4, 5).

A Chinese Pilot in a Neighbourhood of Ningbo

A most complete implementation of the principles of the Handbook has occurred during a one-week workshop for Young Planning Professionals in the city of Ningbo, because children were effectively involved during the workshop. The Ningbo workshop had been initiated by the International Society of City and Regional Planners (ISOCARP) that previously had been supporting the drafting and dissemination of the Handbook on child-responsive urban planning,so to promote thriving and equitable cities where children live in healthy, safe, inclusive, green and prosperous communities. Promoted by the China Urban Planning Society (UPSC), and undertaken by Ningbo Bureau of Nature Resources and Planning(NBNRP) and the Ningbo Urban Planning & Design Institute (NBPI), the workshop took place between 26 and 30 August 20191).

The city of Ningbo is known to be both an economically thriving as a livable city. It has been awarded nine times as "China's Most Happy City".Yet, the question remained whether happiness can be translated to childhood. Children's daily life takes place on the scale of the neighbourhood. Therefore,the workshop concentrated on the upgrading of a pilot neighbourhood, that can serve as a model for other similar community-based upgrading programmes.The Mingdong Community was built in 1996 on a rectangular area defined by four main roads. The total site covers 17.59 hm2, with 120,000 m2floor area constructed. There are 56 residential buildings, 170 households and 550 residents in this community.Zhaohui Experimental Primary School is located in the northeast corner of the community, which is the largest primary school for children of migrant workers in the city. The premise also functions as cultural centre and adult training school. There is a designated community park, a middle school and a sport centre.The community is well serviced by nearby functions like a shopping mall, an art park and a supermarket.The main reason why Mingdong had been selected as a model area for the workshop is the strong presence of children of low- and middle-income families, as well as of migrant workers inside the community.Despite the presence of basic facilities for children in the neighbourhood, there is an urgency to critically review them so to improve their use and improve children's satisfaction. In addition, another element made the case study area particularly challenging and relevant: the community itself has already been involved in the development of a transformation plan,which could be complemented through the workshop with a children's view (Fig. 6).

6 寧波明東社區/View of the Mingdong Community, Ningbo

7 寧波明東社區公園/View of the Community Park, Ningbo

(6.7 圖片版權/Copyright: 延斯·阿茲/Jens Aerts)

8 兒童參與分析及展望/Children's input in analysis and envisioning exercise(圖片版權/Copyright: NBPI)

The workshop brought together 6 tutors and 18 young planning professionals from Ningbo, other Chinese cities and other countries. Together with 15 children in the age between 6 to 12 from four local schools they analysed and proposed a transformation plan for Mingdong community. As part of the research methodology, they were actively involved at every stage of the workshop, from research to envisioning and developing design proposals. They significantly contributed towards articulating the current situation, identifying issues and challenges as they navigated their way through the neighbourhood.They were broadly divided into 3 categories (0-6, 6-12 and 12-18 years) to be able to understand their needs and desires specifically with reference to their age.

Build upon a strong narrative for a "Children's Home", the workshop explored answers on three questions that refer to both sustainable urban development and child's rights:

(1) How is the city perceived and lived by the youngest generation?

With the help of questionnaires and more informal activities such as short walks, children were able to explain their relation with the site, show the everyday spaces of play and ascertain were there any challenges accessing to these spaces. The children also mapped the most frequented routes they used on a daily basis within the neighbourhood. This anthropological exercise also highlighted issues and concerns regarding the lack of access to open spaces,despite their availability. For example, streets within the community boundaries are fully used as parking lots. The designated park area is well used by the elderly, but its design is not attractive for children and does not promote intergenerational interaction.Children also explained that they have little free time to play outside, due to extracurricular activities that prevent them from going out, like extra school hours,hobby classes or doing extra homework (Fig. 7).

(2) How to envision Mindong as a child friendly community?

While envisioning child friendly spaces for Mingdong district, benefits of play in the form of cognitive development, psychological benefits and physical skills were highlighted. Focused group discussions were organised during their playtime in the main playground. This gave the planners an opportunity to relive our own childhoods by being part of the dreams and aspirations of the local children, to imagine accessible, safe and creative community spaces for them. Knowing that children have busy schedules from early days on, it became clear that playfulness should be integrated in a granular network of public spaces that they use while commuting or that is immediately accessible from their home (Fig. 8).

(3) How to take action?

To enable children playing outside more frequently it is necessary to create the conditions where they can safely do so. Currently parents are constantly watching their children because they perceive their neighbourhood as unsafe. Therefore,communities should re-organise internal traffic circulation so to create car-low or car-free areas. A system of safe routes or "ribbons" can then connect all facilities and places important to children.These ribbons need to respect quality design requirements that (i) aim for uninterrupted routes.This enables safe traffic crossings and priority for children in hazardous traffic situations; (ii) promote play everywhere. Play should not be limited to designated areas, but be possible along route; (iii)are recognisable for children. This means that the ribbon needs to be clearly marked, for example with coloured pavement (Fig. 9-11).

9 新流線與安全絲帶系統/The new circulation pattern with the safe ribbons

10 建筑與水系戶外兒童友好空間軸測/Axonometry of child friendly outdoor space between buildings and canals

11 兒童應答型社區的總體計劃/General plan child-responsive community improvement

(9-11 圖片版權/Copyright: ISOCARP)

The Potential Leadership of China in Child-Responsive Urban Planning

China is a nation with a long history of cities,as pivotal centres to develop culture, economy and welfare. Although Chinese urban planning practice still shows its unique capacity to plan fast and at scale, most contemporary urban development schemes feature infrastructure without a human scale: high-rise mono-functional residential areas, car-oriented transportation infrastructure,large building blocks and wide streets with poor walkability. With these new urban settings where air pollution, social isolation and physical boundaries prevail, we pre-set unhealthy conditions to our children. Without any doubt they will suffer more from lung and heart diseases, obesity and diabetes,stress and mental disorders. Moreover, without good health, viruses like COVID-19 will have lethal impact, as research on patients that died has shown.

Looking at China's ongoing urbanisation prospects, in particular the ambitious Belt and Road initiative, there is an opportunity to acknowledge the flaws of previous city planning and to shape our cities in a more human way. This might be the momentum to look for new ways to develop more sustainable models of urbanisation: celebrating children, and focusing on people's health and the love and care all generations should be able to share with each other.The pilot in Ningbo can lead the way for other cities to adopt a child-responsive practice of urban planning and to develop a network of thriving and equitable cities where children live in healthy, safe, inclusive,green and prosperous communities.

注釋/Note

1)關于工作坊期間擬定的提案及更多背景信息可參見:https://isocarp.org/ypp-ningbo-2019/More information on the context and the proposals developed during the workshop are available on-line at https://isocarp.org/ypp-ningbo-2019/.