Purification and Characterization of a Nonylphenol (NP)-degrading Enzyme from Bacillus cereus. Frankland*

YANG Ge (楊革)**, ZHANG Ying (張營) and BAI Yanfen (白艷芬)22 College of Textiles Tianjin Polytechnic University, Tianjin 30060, China Key Lab of Biogeology and Environmental Geology of Ministry of Education, China University of Geosciences,Wuhan 430074, China

1 INTRODUCTION

Alkylphenol polyethoxylates (APEOs) were a group of non-ionic surfactants and the hard-degradable polymer that was found widespread use as detergents,emulsifiers, wetting agents, stabilisers, defoaming agents and intermediates in the synthesis of anionic surfactants. It had been reported that these substances were degraded into more toxic products, mainly as NP[1-3]. In particular, concerns had been expressed regarding the possible endocrine disrupting effects of these‘hormone mimicking’ degradation products [4-9].

In recent years, the development of cleanproduction process for textile industry attracted great interest and therefore, the biodegradation of NP at the desizing stage, which could greatly reduce discharge of NP waste water and minimize damage of cotton fiber in the desizing process, became one of the key points in textile biotechnology [10, 11].Till now, the research about biodegradation of NP was mainly focused on the screening of NP-degrading microorganisms and the characteristics of PVA (polyvinyl alcohol)-degrading enzymes from obtained strains. PVA-degrading enzymes were still not applicable in real industry process due to their low activity and the producing strains of NP-degrading enzyme were limited and they often grew very slowly. Here the recent research of NP biodegradation, including purification and characterization of the NP-degrading enzyme was reported [12-16].

Bacillus cereus. Frankland No. BCF83 was a newly isolated strain from soil in Shandong of China for its high NP-degrading enzyme activity secreted in culture medium. In this study the extracellular NP-degrading enzyme was purified to homogeneity from the fermented broth ofBacillus cereus. Frankland No.BCF83 to investigate its physico-chemical properties.With the determination of partialN-terminal amino acid sequence and its characteristics, it was demonstrated that the purified enzyme was a novel endo NP-degrading enzyme.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Bacterial strain and culture condition

Bacillus cereus. Frankland No. BCF83 was isolated from soil in Shandong of China. Cultures were maintained on nutrient agar slants and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The cells were then inoculated into a 500-ml Erlenmeyer flask containing 200ml liquid medium, cultured at 37 °C for 24-36 h on a shaker. The medium adjusted to pH 7.0 was composed of (g·L-1):1 NP, 1 NH4NO3, 1 yeast extract, 0.5 KH2PO4, 0.2 MgSO4·7H2O, 0.02 FeSO4·7H2O, and 0.1 CaCl2.

2.2 Chemicals

Phenyl-Sepharose CL-4B, DEAE-Sepharose Fast Flow and Sephadex G-150 were purchased from Pharmacia LKB (Uppsala Sweden). SDS (sodium dodecyl sulfate)-PAGE (polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis) protein markers were purchased from Sigma(Santa Clara, USA). Other chemicals were of analytical grade.

2.3 Purification of NP-degrading enzyme

The fermented broth ofBacillus cereus. Frankland No. BCF83 was collected by centrifugation at 8000 g for 10 min, and the proteins fractionated with 50% saturation (NH4)2SO4were collected by centrifugation at 8000 g for 20 min. The protein precipitate was dissolved in 0.8 mol·L-1(NH4)2SO4solution and the insoluble materials were removed by centrifugation at 15000 g for 30 min. The derived supernatant was applied onto a Phenyl-Sepharose CL-4B column (φ1.2 cm×10 cm) preequilibrated with 1 mol·L-1(NH4)2SO4.The column was washed with 1.5 bed volumes of 1 mol·L-1(NH4)2SO4, 2 bed volumes of 0.1 mol·L-1(NH4)2SO4, and eluted with distilled water. The flow rate was maintained at 0.5 ml·min-1. The fractions with NP-degrading enzyme activity were pooled and dialyzed overnight at 4 °C against 10 mmol·L-1tris-HCI buffer with pH 6.2. The dialysate was collected and immediately applied on a DEAE-Sepharose Fast Flow column (φ1.2 cm×4 cm) pre-equilibrated with 10 mmol·L-1tris-HCI buffer with pH 6.2. The flow rate was maintained at 0.25 ml·min-1. The fractions with NP-degrading enzyme activity were pooled, 10 times concentrated and kept at -20 °C until use.

ForN-terminal amino acid sequencing, the enzyme fraction was further purified by reverse-phase HPLC (High Performance Liquid Chromatography).NP-degrading enzyme fractions derived from DEAE-Sepharose Fast Flow were loaded on a Zorbas 300SBCN column (du Pont,φ250 mm×4.6 mm I. D.),and the column was developed with acetonitrile gradient (0-10% for 20 min) supplemented with 0.1%trifluoroacetic acid (TFA). The elution pattern was monitored by absorbance at 220 nm and 280 nm. The major peak was collected and lyophilized for automatic amino acid sequencing.

2.4 Enzymatic activity assay

Two methods for enzymatic activity assay were used in this work. For rapidly tracing NP-degrading enzyme activity during the chromatographic separation processes, 100 μl of each fraction was mixed with 2 ml 10 g·L-1nonylphenol (NP) in 50 mmol·L-1acetate buffer (pH 7.0) and incubated at 50 °C for 10 min.The enzyme activity was calculated from a standard curve obtained with known concentration of nonylphenol (NP). One unit of NP-degrading enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that liberated 1 μmol NP-degrading per min at pH 7.0 and 50 °C.Negative control tubes contained all components except substrate, and blanks contained all components except the enzyme.

2.5 Electrophoresis

SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDSPAGE) was performed. The proteins were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R-225. For isoelectric focusing (IEF) experiment, about 5 μg of sample proteins in 20 μl solution were loaded to a precasted capillary gel with 0.75% Ampholine (pH range 3.5-10), and run under 200 V for 5 h. Amyloglucosidase (pl 3.6), trypsin inhibitor (pI 4.6), β-lactoglubin A (pI 5.1), conalbumin (pI 6.0), myoglobin (pI 6.8, 7.2), lentil lectin(pI 8.2, 8.6, 8.8), and trypsinogen (pI 9.3) were used as markers.

2.6 Zymogram

To identify the protein of NP-degrading enzyme,zymographic approach was applied on samples derived from DEAE Fast Flow chromatography. Samples were separated on 10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis at pH 8.3. As soon as the electrophoresis was finished, the gel was immediately placed on an agarose slab gel containing 10 g·L-1nonylphenol. After incubation for 1.5 h at 37 °C, a transparent band could be seen on the agarose slab. The sections of the polyacrylamide gel overlapping with the transparent band were carefully cut out and pestled with the transparent band were carefully cut out and pestled with sample buffer in an Eppendorf tube. The derived paste was analyzed on 10% SDS-PAGE.

2.7 Gel filtration chromatography

Gel filtration chromatography was used for determination of molecular weight of molecular weight of NP-degrading enzyme. Sephadex G-150 was packaged in a 1.2 cm×60 cm column and equilibrated with 10 mmol·L-1tris-HCI buffer (pH 6.2) at a flow rate of 0.15 ml·min-1. About 0.4 ml concentrated enzyme obtained from the DEAE Fast Flow column was applied to the column and eluted with the same buffer.Protein profile was monitored at 280 nm. The molecular weight was estimated from a standard curve obtained from the proteins with their relative molecular mass known [17].

2.8 N-Terminal amino acid sequencing

Samples obtained from reverse-phase HPLC were lyophilized and subjected toN-terminal amino acid sequencing on an automatic protein sequencer( Model 473A, Applied Biosystems Inc., USA).

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

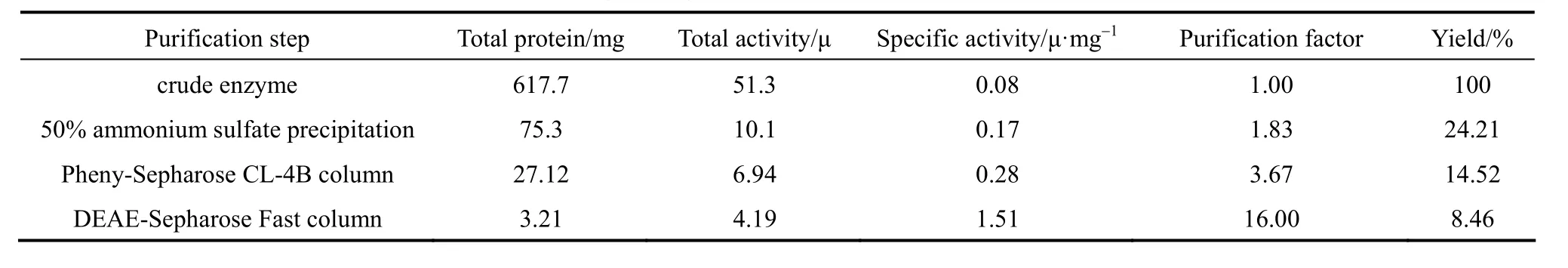

3.1 Purification of NP-degrading enzyme

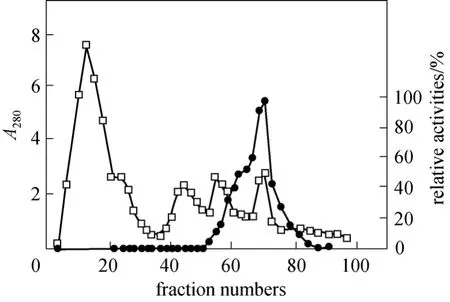

A NP-degrading enzyme secreted by this new strain ofBacillus cereus. Frankland No. BCF83 was purified for further study. Proteins in the fermented broth were recovered with (NH4)2SO4precipitation at 50% saturation. The protein precipitates were dissolved in 0.8 mol·L-1(NH4)2SO4solution and separated by Phenyl-Sepharose CL-4B hydrophobic interaction chromatography. In a typical separation, 30 ml of the sample solution containing 68.4 mg of crude proteins was applied to a 1.2 cm×10 cm column, and developed as described in Section 2. Four protein peaks were detected at 280 nm as shown in Figs. 1 and 2.NP-degrading enzyme activity was only found in the last peak eluted with distilled H2O.

Figure 1 Elution profile of NP-degrading enzyme on Phenyl-Sepharose CL-4B column

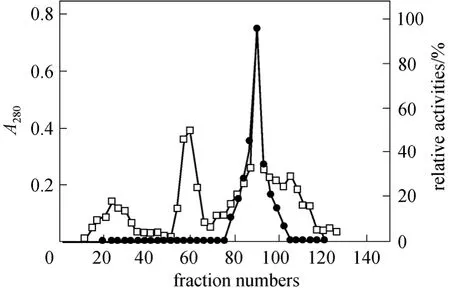

Figure 2 Elution profile of NP-degrading enzyme on DEAESepharose Fast Flow column chromatography

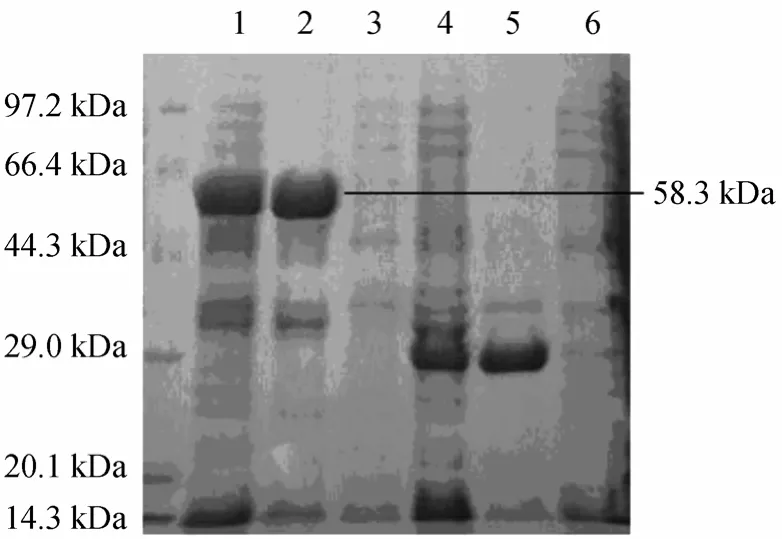

The fractions with NP-degrading enzyme activity were pooled and dialyzed against 10 mmol·L-1tris-HCl buffer (pH 6.2) overnight. The dialysate containing 23.46 mg proteins was then applied onto a DEAESepharose Fast Flow column for anion-exchange chromatography described as Section 2. The NP-degrading enzyme activity was detected in the third peak as shown in Fig. 2. When this peak was analyzed on 10%SDS-PAGE, a protein band with relative molecular mass of 58.3 kDa (Fig. 3) was shown. Meanwhile,zymographic approach was applied to identify the protein with NP-degrading enzyme activity. Table 1 is the summary of purification.

Figure 3 SDS-PAGE analysis of NP-degrading enzyme under various conditions

3.2 N-terminal amino acid sequence

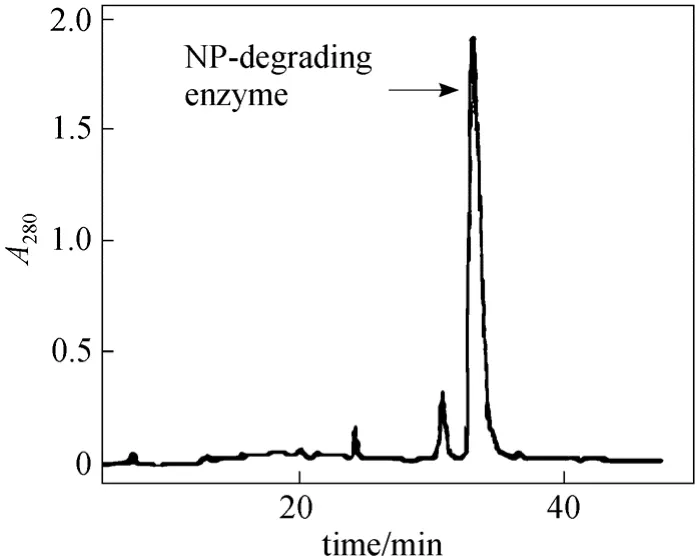

ForN-terminal sequencing, the enzyme fractions from DEAE-Sepharose Fast Flow were further purified by reverse-phrase HPLC. As shown in Fig. 4,only one protein peak was detected. The protein peak was collected, lyophilized and subjected to amino acid sequencing. The first 10 amino acids in theN-terminal sequence were determined to be ASVNSIKIGY. The sequence was blasted against GenBank, however, no NP-degrading enzyme known showed significant similarity with this sequence.

Figure 4 Elution profile of NP-degrading enzyme on reverse-phase HPLC

Table 1 Purification of NP-degrading enzyme from Bacillus cereus. Frankland No. BCF83

3.3 Characteristics of the purified NP-degrading enzyme

The difference between relative molecular mass of proteins in DEAE-Sepharose Fast Flow fractions and HPLC fractions implied a dimer structure of NP-degrading enzyme. A series of experiments or further characterization of this protein was performed.The purified NP-degrading enzyme was subjected to isoelectric focusing analysis and the pI of the NP-degrading enzyme was found to be 5.5. On the result of RPC (Reversed Phase Chromatography), the molecular weight of NP-degrading enzyme was determined to be around 56 kDa (Fig. 4), and other two peaks were not an enzyme activity. The relative molecular mass of NP-degrading enzyme protein on SDS-PAGE differed depending on conditions. If the NP-degrading enzyme in DEAE fractions was heated in boiling sample buffer before SDS-PAGE analysis,the protein band on SDS-PAGE was at the position of 58.3 kDa. After treatment of the enzyme with 4%2-mercaptoethanol, the relative molecular mass of the purified enzyme was still 58.3 kDa on SDS-PAGE,implying that disulfide bond was not involved in the formation of NP-degrading enzyme with 8 mol·L-1urea at 50 °C for 30 min and could cause a total loss of enzymatic activity and a shift of the protein band position from 58.3 kDa to 28.5 kDa on SDS-PAGE(Fig. 3). After dialysis of the enzymes depolymerized by 8 mol·L-1urea, heating at 100 °C or 0.1% TFA treatment against 10 mmol·L-1tris-HCl buffer (pH6.2),the enzymatic activity recovered by 79%, 75% and 87%, respectively. The dimer was found to be the major component revealed by SDS-PAGE (data not shown).These results strongly suggest that the NP-degrading enzyme had a homodimer structure based on hydrophobic interaction. After incubation the NP-degrading enzyme with 8 mol·L-1urea and then dialyzing it against 40% alcohol, the free NP-degrading enzyme subunits were obtained, which utterly lost the activity(the NP-degrading enzyme in 40% alcohol still exhibited hydrolytic activity). It was thus concluded that the compact structure of the dimer is necessary for NP-degrading enzyme activity.

Up to now, no NP-degrading enzyme with dimer structure from bacteria had been reported. In other species only an insect inhibitor/endo NP-degrading enzyme from plant origin was shown to have a structure of dimer. By this fact, as well as the result of theN-terminal amino acid sequence, it was concluded that the NP-degrading enzyme produced byBacillus cereus. Frankland No. BCF83 was a novel NP-degrading enzyme with an unusual structure.

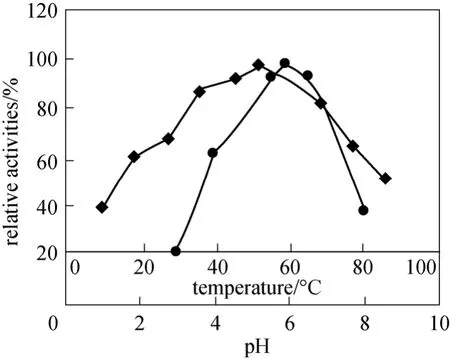

Figure 5 Effect of pH (◆) and temperature (●) on enzymatic activity of the purified NP-degrading enzyme

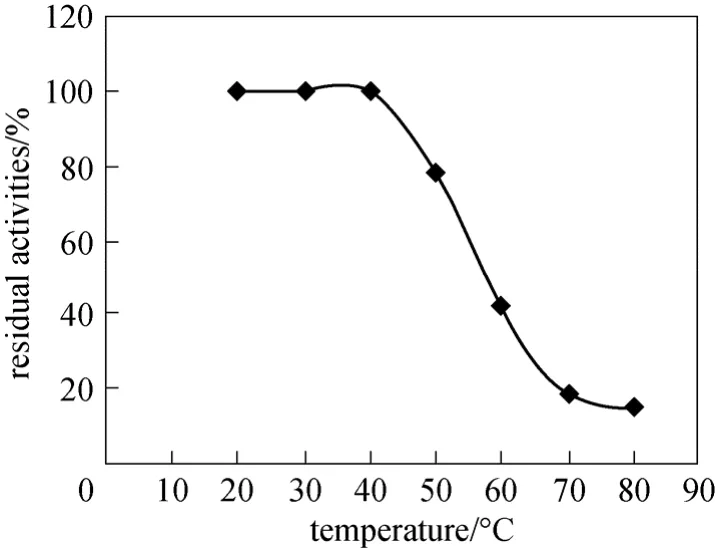

Figure 6 Effect of temperature on stability of the purified NP-degrading enzyme

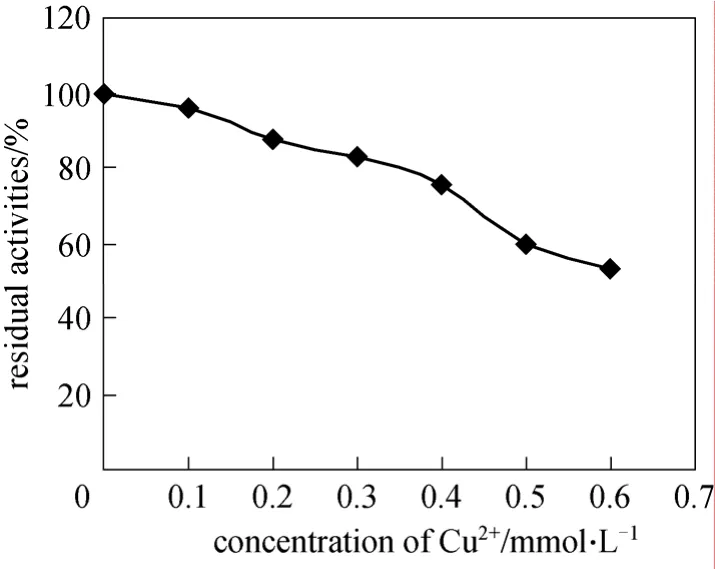

Figure 7 Effect of Cu2+ion on enzymatic activity of the purified NP-degrading enzyme

The optimal conditions for enzymatic reaction were studied systemically. 6μg purified NP-degrading enzyme was used to determine its characteristic. The optimal pH of the NP-degrading enzyme was 6.0 (Fig. 5),and the NP-degrading enzyme was stable and could hydrolyze collidal nonylphenol at a wide pH range(from pH 4.0 to pH 8.0). The NP-degrading enzyme exhibited the highest activity at 60 °C and retained high activity even over 80 °C (Fig. 5). However, in the absence of substrate the NP-degrading enzyme lost its activity markedly above 60 °C (Fig. 6), inferring that the substrate could protect the active center of the NP-degrading enzyme from denaturation.

TheBacillus cereus. Frankland No. BCF83 NP-degrading enzyme could be inactivated by Cu2+ion (Fig. 7). After incubation with 0.5 mmol·L-1Cu2+at pH 6.0 and 30 °C for 30 min, only 60% of the enzyme activity remained.

4 CONCLUSIONS

TheBacillus cereus. Frankland No. BCF83 NP-degrading enzyme was highly stable (retaining higher than 80% activity) in a wide range of pH (pH 6.0 to 10.0) and temperature (from 35 °C to 72 °C). In comparison, the NP-degrading enzyme fromBacillus cereus. Frankland No. BCF83 and other strains [18-21]exhibit their enzymatic activities in a more narrow temperature range and are less stable. Furthermore, the purified NP-degrading enzyme fromBacillus cereus.Frankland No. BCF83 was strongly resistant to the hydrolysis by trypsin. A common condition was not sufficient for trypsin digestion of the NP-degrading enzyme. The NP-degrading enzyme in fermented broth could be kept at 4 °C for at least two months without loss of enzymatic activity. The crude fermented broth of theBacillus cereus. Frankland No.BCF83 NP-degrading enzyme could be widely applied as a new tool for clean-production process of textile.

1 Ferguson, P.L., Brownawell, B.J., “Degradation of nonylphenol ethoxylates in estuarine sediment under aerobic and anaerobic conditions”,Environ.Toxicol.Chem., 22, 1189-1199 (2003).

2 Xiao, C.B., Ning, J., Yan, H., Sun, X.D., Hu, J.Y., “Biodegradation of aniline by a newly isolatedDelftiasp. XYJ6”,Chin.J.Chem.Eng., 17 (3), 500-505(2009).

3 M?nsson, N., S?rme L., Wahlberg, C., Bergb?ck, B., “Sources of alkylphenols and alkylphenol ethoxylates in wastewater—a substance flow analysis in Stockholm, Sweden”,Water,Air,& Soil Pollut:Focus, 8, 445-456 (2008).

4 Ohtsubo, Y., Kudo, T., Tsuda, M., Nagata, Y., “Strategies for bioremediation of polychlorinated biphenyls”,Appl.Microbiol.Biotechnol., 65, 250-258 (2004).

5 Wackett, L.P., Sadosky, M.J., Martinez, B., Shapir, N., “Biodegradation of atrazine and related striazine compounds from enzymes to field studies”,Appl.Microbiol.Biotechnol., 58, 39-45 (2002).

6 Cravotto, G., Carlo, S.D., Binello, A., Mantegna, S., Girlanda, M.,Lazzari, A., “Integrated sonochemical and microbial treatment for decontamination of nonylphenol-polluted water”,Wate,Air,& Soil Pollution, 187 (1-4), 353-359 (2008).

7 Jontofsohn, M., Pfister, G., Severin, G., Schramm, K.W., Hartmann,A., Schloter, M., “Bacterial community structure in lake sediments of microcosms contaminated with nonylphenol”,Journal of Soils and Sediments, 2 (4), 211-215 (2002).

8 Mai, H., EI-Dakdoky, Mona, A.M., HelaI, “Reproductive toxicity of male mice after exposure to nonylphenol”.Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 79 (2), 188-191 (2007).

9 Beklioglu, M., Banu Akkas, S., Elif Ozcan, H., Bezirci, G., Togan, I.,“Effects of 4-nonylphenol, fish predation and food availability on survival and life history traits ofDaphnia magnastraus”,Ecotoxicology, 19 (5), 901-910 (2010).

10 Hermuth, K., Leuthner, B., Heider, J., “Operon structure and expression of the genes for benzylsuccinate synthase in Thauera aromatica strain K172”,Arch.Microbiol., 177, 132-138 (2002).

11 Krieger, J., Roseboom, W., Albracht, S.P., Spormann, A.M., “A stable organic free radical in anaerobic benzylsuccinate synthase ofAzoarcussp. strain T”,J.Biol.Chem., 276, 12924-12927 (2001).

12 Song, B., Palleroni, N.J., Haggblom, M.M., “Isolation and characterization of diverse halobenzoate-degrading denitrifying bacteria from soils and sediments”,Appl.Environ.Microbiol., 66, 3446-3453(2000).

13 Lu, J., He, Y.L., Wu, J., Jin, Q., “Aerobic and anaerobic biodegradation of nonylphenol ethoxylates in estuary sediment of Yangtze River,China”,Environmental Geology, 57 (1), 1-8 (2009).

14 Liu, X., Tani, A., Kimbara, K., Kawai, F., “Metabolic pathway of xenoestrogenic short ethoxy chain-nonylphenol to nonylphenol by aerobic bacteria,Ensifersp. strain AS08 andPseudomonassp. strain AS90”,Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 72 (3), 552-559(2006).

15 Latorre, A., Lacorte, A., Barceló, D., “Presence of nonylphenol, octyphenol and bisphenol a in two aquifers close to agricultural, industrial and urban areas”,Chromatographia, 57 (1-2), 111-116 (2003).

16 Park, S.Y., Choi, J., “Genotoxic effects of nonylphenol and bisphenol a exposure in aquatic biomonitoring species: freshwater crustacean,daphnia magna, and aquatic midgechironomus riparius”,Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 83 (4),463-468 (2009).

17 Chen, M., Yao, S.J., Zhang, H., Liang, X.L., “Purification and characterization of a versatile peroxidase from edible mushroom Pleurotus eryngii”,Chin.J.Chem.Eng, 18 (5), 824-829 (2010).

18 Morgan, P., Watkinson, R.J., “Microbiological methods for the clean up of soil and groundwater contaminated with halogenated organic compounds”,FEMS Microbiol.Rev. 63, 277-300 (1989).

19 Takasu, T., Iles, A., Hasebe, K., “Determination of alkylphenols and alkylphenol polyethoxylates by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography and solid-phase extraction”,Anal.Bioanal.Chem., 372, 554-561 (2002).

20 Zhang, X., Young, L.Y., “Carboxylation as an initial reaction in the anaerobic metabolism of naphthalene and phenanthrene by sulfidogenic consortia”,Appl.Environ.Microbiol., 63, 4759-4764 (1997).

21 Zhang, X., Sullivan, E.R., Young, L.Y., “Evidence for aromaticring reduction in the biodegradation pathway of carboxylated naphthalene by a sulfate-reducing consortium”,Biodegradation, 11, 117-124(2002b).

Chinese Journal of Chemical Engineering2011年4期

Chinese Journal of Chemical Engineering2011年4期

- Chinese Journal of Chemical Engineering的其它文章

- Adsorptive Recovery of Uranium from Nuclear Fuel Industrial Wastewater by Titanium Loaded Collagen Fiber*

- Salting-out Extraction of 2,3-Butanediol from Jerusalem artichoke-based Fermentation Broth*

- Investigation of Mg2+/Li+ Separation by Nanofiltration*

- Vapor-Liquid Equilibrium of Ethylene + Mesitylene System and Process Simulation for Ethylene Recovery*

- Sponge Effect on Coal Mine Methane Separation Based on Clathrate Hydrate Method*

- Modeling of Surface Tension and Viscosity for Non-electrolyte Systems by Means of the Equation of State for Square-wellChain Fluids with Variable Interaction Range*