Leaching of Electronic Waste Using Biometabolised Acids*

M. Saidan, B. Brown and M. Valix**

Material and Mineral Processing Research Unit, School of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, The University of Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia

1 INTRODUCTION

Information and communication technology has brought huge technical benefits and wealth. However,the phenomenal worldwide growth of as much as 23%per annum in the electrical and electronics industries[1] have generated vast amounts of electronic waste, or“e-waste”. The average 12% annual growth of e-waste is about three times that of municipal waste streams [2].Millions of tonnes of these toxins are released into air,water and soil each year from landfilling, incineration,and chemical and thermal treatment in unregulated recycling processes; these technologies are expensive,achieve only partial reclamation, and are hazardous for e-workers when unregulated [3]. The challenge is to develop sustainable recycling technologies to address the volume and complexity of this waste using cost-effective and ecologically sensitive methods.

The possibility of a solution that is both economically feasible and environmentally sustainable has encouraged a variety of active research into the area in recent years. Perhaps the most promising of these technologies is through the use of naturally occurring biological micro-organisms and their metabolic products in extracting valuable metals from the waste [4-7].The increase in interest in the use of biohydrometallurgical route for re-processing wastes is driven by the fact that this method is environmentally sound with a huge potential to lower operational cost and energy requirements.

A key factor in developing this technology is matching the potency of the organisms with the requirements for dissolving the metallic fractions of e-wastes. Traditionally chemolithoautotrophs bacteria(e.g.,Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidansandAcidithiobacillus thiooxidans) have been applied in leaching sulphide minerals and fungi (e.g.,Aspergillus niger) have been used in dissolving oxide minerals and waste [8, 9].The objective of this study is to examine the roles of the metabolic acidic products of autotrophic and heterotrophic organisms in the bioleaching of metals from e-wastes. In this study synthetic organic and mineral acids were used to decouple their roles.

2 EXPERIMENTAL

2.1 Materials

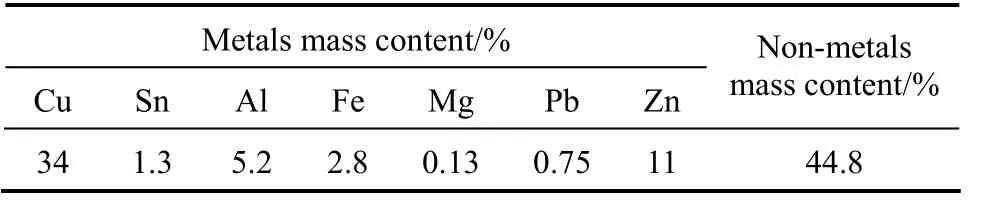

The copper-rich e-waste powder was obtained from Total Union PCB Recycle Ltd, Hong Kong. This material was used as received. The particle size is in the range of 350 to 720 μm. The composition of this e-waste fraction is shown in Table 1. As shown the metallic component of the waste is 55.2% (by mass),which consisted primarily of copper. The remaining components, which contributes 44.8% (by mass) of the waste, consist of glass, epoxy and minor quantities of flame retardants. The toxicity of heavy metals and flame retardants is quite well established and is part of the challenge in re-processing e-wastes.

Table 1 Composition of copper rich waste

2.2 Leaching tests

Chemical leaching tests were carried out in 100 ml batch reactors using 50 ml of acid with 1% pulp density of waste at temperatures from 70 and 90 °C whilst shaken at 1000 r·min-1. The copper rich waste was leached in reagent grade citric, malic, lactic, oxalic

and sulphuric acids. Because each of the acids used have different dissociation constants, the leaching behaviour was correlated to the solution pH which reflects acid activities rather than acid concentrations. In these tests, the initial pHs of the acids used were from 1.5 to 2.0 and these were not adjusted during the test.The pH 1.5, 1.75 and 2.0 were obtained from the following concentrations of acids: citric acid (1.4 mol·L-1, 0.5 mol·L-1, and 0.13 mol·L-1), malic acid(0.56 mol·L-1, 1.25×10-2mol·L-1, 4.7×10-4mol·L-1),lactic acid (3.3 mol·L-1, 1.4 mol·L-1and 0.6 mol·L-1)and sulphuric acid (6.2×10-2mol·L-1, 3.5×10-2mol·L-1,2.2×10-2mol·L-1). Leaching was performed for 6 h,after which the solution were filtered and analysed for dissolved metals using Varian Vista AX CCD Inductively Coupled Plasma Atomic Emission Spectrometer(ICP-AES) using standard procedures. The pH was monitored during leaching with a dedicated pH-mV-temp meter WP-80D (TPS Pty. Ltd., Australia).

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1 Secondary reactions

Secondary reactions are reactions other than metal leaching which can influence the dissolution or stability of the metals solution [10]. These can include the adsorption of the metal complexes on the epoxy waste and precipitation of the dissolved metals. Occurrence of these reactions during leaching can veil the true potential of acids to dissolve the metallic fractions of the waste. Conditions that are chosen to assess the activity of the acids must therefore overcome or reduce the effects of these reactions. Brown [11] has shown that leaching at pH below 4.5 can overcome metal complex adsorption on the epoxy fractions of the waste and these conditions also avoided metal hydroxyl precipitation and passivation. All leaching tests were conducted at pH from 1.5 to 2.0.

3.2 Leaching with organic and mineral acids

3.2.1Effect of pH

Heterotrophic micro-organisms generate various metabolic products including exopolysaccharides,amino acids and proteins with the ability to dissolve the metallic fractions from e-wastes [12]. However organic acids are considered to have a central role in dissolving metals through their supply of protons and ligands [13]. Organic acids can dissolve the metallic fractions of e-wastes by various mechanisms including acidification and complexation. The process of metal (for example copper) dissolution in acid involves a reduction couple; the cathodic reduction of protons to hydrogen (Reaction 1) and the anodic oxidation of the metal (Reaction 2):

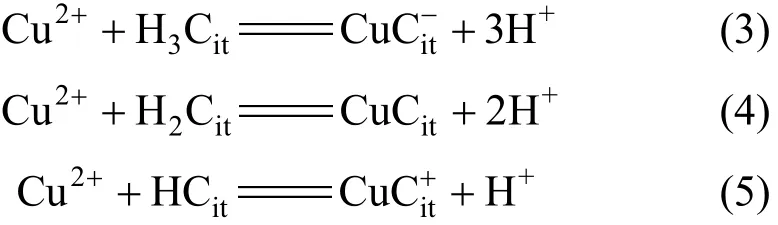

The ligands in organic acids, for example citrate (Cit)from citric acid, form stable metal complexes, which can increase the solubility of metals in solution:

The organic acids that are metabolised by fungi through the Kreb cycle include malic, lactic, oxalic citric, α-ketoglutaric, fumaric, succinic, pyruvic acids[14]. In this study only the first four acids were considered. These acids were selected based on their ability to dissociate in solution and their relatively higher solubility in water, which contributes to their overall acid strength. Leaching tests in this study focused on the dissolution of the copper metal.

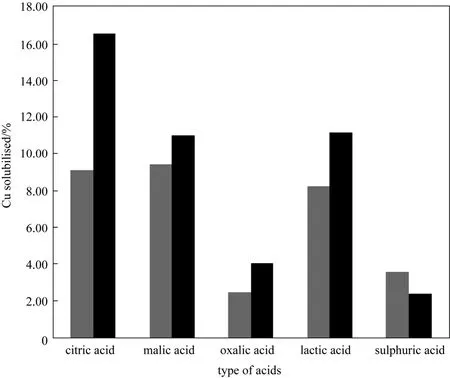

The copper solubilised by various organic acids were compared at typical pH range that would mimic a fermentation process (see Fig. 1). These pHs are

Figure 1 Copper solubilised by organic and mineral acids as a function of solution pH after 6 h of leaching at 70 °C and 1000 r·min-1 with 1% pulp density

from 1.5 to 2.0 and leaching was conducted for 6 h at 90 °C and 1000 r·min-1. Reducing the pH of the organic acids appears to result in lower copper solubilisation, in particular in citric and lactic acids. This is attributed to the acid dissociation. Brown [11] has shown that at pH below 2.0 the dominant citric acid species is the un-dissociated citric acid. Dissociation of citric acid to its ligands only begins above pH 2.0.

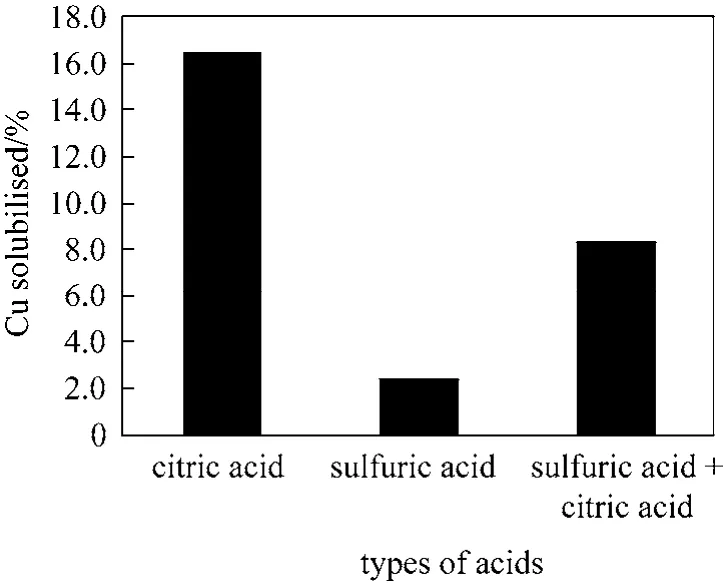

Leaching of metallic copper in organic acid is compared with sulphuric acid in Fig. 2. The metallic fractions from e-waste can also be mobilised using the mineral acid generated by metabolism of sulphur based compounds (e.g., FeS2) or elemental sulphur byAcidithiobacillus thiooxidans and ferrooxidans[15].Unlike organic acids, the effect of pH on copper solubilised by sulphuric acid in Fig. 2 show dissolution is promoted by decreasing pH. This is attributed to the strong dissociation constant of sulphuric acid. Casaset al. [16] has shown that sulphuric acid speciates primarily to the bisulphate (4HSO-) and hydrogen ion(H+) at pH below 1.0 and to a combination of the bisulphate and sulphate () ions at pH below 3.5.

Figure 2 Comparing the acid activities of organic and mineral acids at pH 2.0 leached for 6 h at 90 °C and 1000 r·min-1 with 1% pulp density

3.2.2Acid activities

The acid activities in dissolving copper were shown to be influenced by the ability of the leaching reagents to promote reactions including precipitation,complexation, acidification and hydrolysis.

A comparison of the acid activities in Fig. 1 show the order of activity for the acids is dependent on pH.For organic acids this order malic > citric > lactic >oxalic acids. Although oxalic acid has the highest dissociation constant among the organic acids tested (see Table 2), it has the least Cu dissolution. This is attributed to the ability of oxalic acid to form stable copper oxalate precipitates with dissolved copper [18]. Comparison of acid activity at pH 2.0, where effective dissociation of the organic acids begin, shows that malic acid is marginally more effective in dissolving copper but in general there is very little difference between the acids,which is consistent with the similarity of their dissociation constants. In comparison sulphuric acid has the highest activity at pH 1.5, but the lowest at pH 2.0.

The addition of citric acid to sulphuric acid at pH 2.0 improved the recovery of copper relative to sulphuric acid alone, however it is lower compared to citric acid alone (see Fig. 2). This suggests the complexation of copper with citrate assisted in metal dissolution far outweighs the hydrolysis achieved by sulphuric acid at pH 2.0. The sulphate ion is present as the major species at pH 2.0, thus the lower copper solubilisation at pH 2.0 in sulphuric acid suggest sulphate ion has a lower solubilising property in comparison to the bisulphate ion [16].

3.2.3Effect of temperature

Temperature is an important environmental factor that can influence the bioleaching of e-wastes by affecting both the biological activity and chemical leaching of the waste. The effect of temperature on copper solubility in organic acids and sulphuric acid at pH 2.0 is shown in Fig. 3. The copper dissolution in sulphuric acid decreased with increasing temperature.This behaviour is typical of most divalent metals [19].However in the presence of organic acids, increasing temperature increased copper solubility. This suggests the copper complexation is an activated reaction.

3.2.4Effect of time

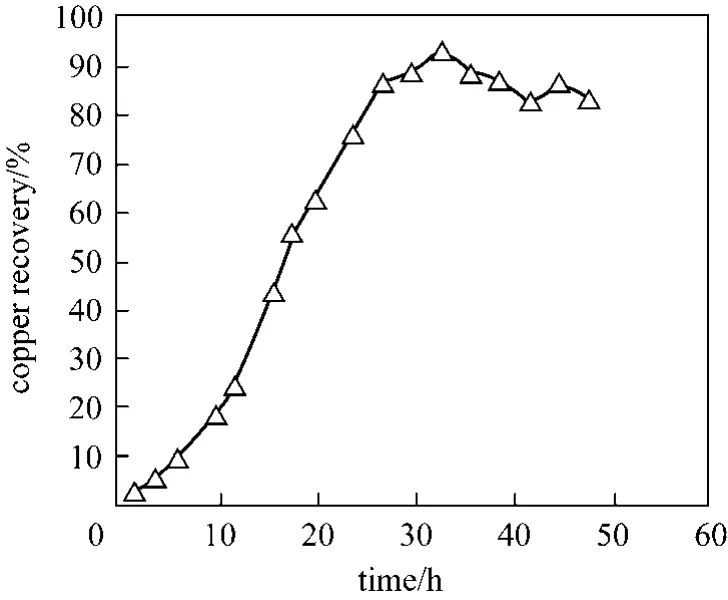

Copper solubility in citric acid at initial pH 1.7 and 90°C as a function of time is shown in Fig. 4. As shown about 94% of copper is solubilised in 33 h,demonstrating the potential efficacy of bioleaching as a method of recovering metals from e-waste.

Table 2 Summary of the dissociation constants of the organic acids [17]

Figure 3 Effect of temperature on copper solubilised by organic and mineral acids leached for 6 h at an initial pH of 2.0 at 1000 r·min-1 with 1% pulp density■ 70 °C; ■ 90 °C

Figure 4 Copper dissolution as a function of time leached with citric acid at pH 1.7 at 1000 r·min-1 at 90 °C with 1%pulp density

4 CONCLUSIONS

Most bioleaching are typically achieved at pH 2.0.A comparison of copper solubility using various metabolic acids at pH 2.0 suggest that organic acids metabolised by heterotrophic fungi organisms are generally more effective in dissolving copper metal than sulphuric acid generated byAcidithiobacillusbacteria.However at lower pH (1.5), sulphuric acid provided greater dissolution. These results suggest that complexation of the organic acids predominate at the higher pH and the acidification process, promoted by the stronger mineral acid, dominates at the lower pH.There is generally very little difference in the activity of the organic acids at pH 2.0, with the exception of oxalic acid, which appear to promote the precipitation of copper. Temperature is shown to reduce copper solubility in sulphuric acid but in the presence of organic acids, copper solubility increased with temperature. Overall copper dissolved (94%) in citric acid at pH 1.7 demonstrate the potential of bioleaching as a method for reprocessing e-wastes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported under Australian Research Council’s Discovery Project’s funding scheme(DP1096342).The authors would also like to acknowledge the support of Li Tong Group towards this project.

1 Brandl, H., Bosshard R., Wegmann M., “Computer-munching microbes:metal leaching from electronic scrap by bacteria and fungi”,Hydrometallurgy, 59, 319-326 (2001).

2 Environment Victoria, “Environmental report card on computers 2005: computer waste in Australia and the case for producer responsibility”, Environment Victoria (2005), p. 17. http://www.envict.org.au/file/EWaste_blue_report_card.pdf, accessed 9 July (2006).

3 Menad, N., Bjorkman, B., Allain, E.G., “Combustion of plastics contained in electric and electronic scrap”,Resources Conserv.Recycl.,24, 65-85 (1998).

4 Valix, M., Usai, F., Malik, R., “Fungal bio-leaching of low grade laterite ores”,Minerals Eng., 14 (2), 197-203 (2001).

5 Bosecker, K.,”Bioleaching: metal solubilization by microorganisms”,FEMS Microbiol.Rev., 20 (3/4), 591-604 (1997).

6 Le, L., Tang, J., Ryan, D., Valix, M., “Bioleaching nickel laterite ores using multi-metal tolerant Aspergillus foetidus organism”,Minerals Eng., 19 (12), 1259-1265 (2006).

7 Ilyas, S., Anwar, M.A., Niazi, S.B., Afzal Ghauri, M., “Bioleaching of metals from electronic scrap by moderately thermophilic acidophilic bacteria”, Hydrometallurgy, 88 (1-4), 180-188 (2007).

8 Jain, N., Sharma, D.K., “Biohydrometallurgy for nonsulfidic minerals—A review”, Geomicrobiol. J., 21 (3), 135-144 (2004).

9 Watling, H.R., “The bioleaching of sulphide minerals with emphasis on copper sulphides—A review”, Hydrometallurgy, 84 (1/2), 81-108(2006).

10 Valix, M., Usai, F., Malik, R., “The electro-sorption properties of nickel on laterite gangue leached with an organic chelating acid”,Minerals Engineering, 14, 205-215 (2001).

11 Brown, B.,”Bioleaching of e-waste”, Master Thesis, University of Sydney, Sydney (2009).

12 Welch, S.A., Barker, W.W., Banfield, J.F., “Microbial extracellular polysaccharides and plagioclase dissolution”, Geochim. Cosmochim.Acta, 63 (9), 1405-1419 (1999).

13 Gadd, G.M., “Fungal production of citric and oxalic acid: Importance in metal speciation, physiology and biogeochemical processes”,Advances in Microbial Physiology, Poole, P.K., ed., Academic Press,47-92 (1999).

14 Khachatourians, G.G., Arora, D.K., “Applied mycology and biotechnology for agriculture and foods”, Applied Mycology and Biotechnology, George, G.K., Dilip, K.A., eds., Elsevier, 1-11 (2001).

15 Schippers, A., Sand, W., “Bacterial leaching of metal sulfides proceeds by two indirect mechanisms via thiosulfate or via polysulfides and sulfur”, Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 65 (1), 319-321 (1999).

16 Casas, J.M., Alvarez, F., Cifuentes, L., “Aqueous speciation of sulfuric acid-cupric sulfate solutions”, Chem. Eng. Sci., 55 (24),6223-6234 (2000).

17 Weast, R.C., Astle, M.J., Beyer, W.H., CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, CRC Press, Boca Raton, Floria, B-219 (1984).

18 Santos, A., Yustos, P., Quintanilla, A., Ruiz, G., Garcia-Ochoa, F.,“Study of the copper leaching in the wet oxidation of phenol with CuO-based catalysts: Causes and effects”, Appl. Catal. B Envir., 61(3/4), 323-333 (2005).

19 Palmer, D.A., Benezeth, P., Simonson, J.M., “Solubility of copper oxides around the water/steam cycle”, Power Plant Chem., 6 (2),81-88 (2004).

Chinese Journal of Chemical Engineering2012年3期

Chinese Journal of Chemical Engineering2012年3期

- Chinese Journal of Chemical Engineering的其它文章

- Analysis of Absorption and Reaction Kinetics in the Oxidation of Organics in Effluents Using a Porous Electrode Ozonator*

- Flame Imaging in Meso-scale Porous Media Burner Using Electrical Capacitance Tomography*

- Modelling and Fixed Bed Column Adsorption of Cr(VI) onto Orthophosphoric Acid-activated Lignin

- Advances in Large-eddy Simulation of Two-phase Combustion (I)LES of Spray Combustion*

- Top-cited Articles in Chemical Engineering in Science Citation Index Expanded: A Bibliometric Analysis

- Adsorptive Removal of Para-chlorophenol Using Stratified Tapered Activated Carbon Column