PD-L1 expression associated with better response to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors

Rafael Rosell, Ramón Palmero

1Catalan Institute of Oncology, Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol, Badalona 08916, Spain;2Germans Trias i Pujol Health Sciences Institute and Hospital, Campus Can Ruti, Badalona 08916, Spain;3Instituto Oncológico Dr Rosell, Quiron Dexeus University Hospital, Barcelona 08028, Spain;4Pangaea Biotech, Barcelona 08028, Spain;5Molecular Oncology Research (MORe) Foundation, Barcelona 08028, Spain;6Thoracic Oncology Unit, Department of Medical Oncology, Catalan Institute of Oncology, L’Hospitalet, Barcelona 08908, Spain

EDITORIaL

PD-L1 expression associated with better response to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors

Rafael Rosell1-5, Ramón Palmero6

1Catalan Institute of Oncology, Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol, Badalona 08916, Spain;2Germans Trias i Pujol Health Sciences Institute and Hospital, Campus Can Ruti, Badalona 08916, Spain;3Instituto Oncológico Dr Rosell, Quiron Dexeus University Hospital, Barcelona 08028, Spain;4Pangaea Biotech, Barcelona 08028, Spain;5Molecular Oncology Research (MORe) Foundation, Barcelona 08028, Spain;6Thoracic Oncology Unit, Department of Medical Oncology, Catalan Institute of Oncology, L’Hospitalet, Barcelona 08908, Spain

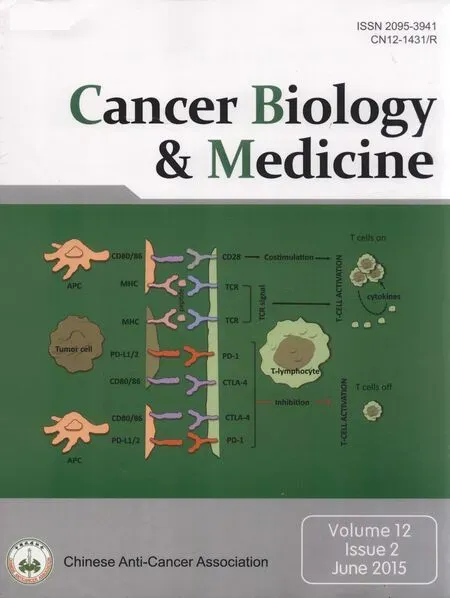

Cancer evades host immune surveillance by using immune checkpoints, which are inhibitory pathways crucial for maintaining self-tolerance1. Tumor cells express multiple inhibitory ligands, and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) express a variety of inhibitory receptors. Inhibitory receptors cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) and programmed death-1 (PD-1)2are the most studied immune checkpoint receptors. Activation of PD-1 and the programmed cell death ligand-1 (PD-L1) signal pathway result in the formation of an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment, which causes tumor cells to escape organism immune surveillance. Tumor cells that escape immunosurveillance can become clinically detectable and can induce an immunosuppressive state through production of cytokines and growth factors, as well as by recruiting T-regulatory cells (T-regs) and myeloidderived suppressor cells. The PD-1 receptor is a member of the immunoglobulin B7-CD28 family, is a negative regulator of T-lymphocyte activation, and can be expressed on TILs, similar to activated CD4+T, CD8+T, B, natural killer T, mononuclear cells, and dendritic cells. PD-L1 is expressed in many cancers, including nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Immune cells play an important part in blocking the “cancer immunity cycle” by binding PD-11. Inhibition of the CTLA-4 and PD-1 pathways has been shown to enhance intratumoral immune responses in numerous preclinical studies, and blockade of immune checkpoints has ushered in a new era in cancer treatment1.

Treatment strategies for NSCLC include chemotherapy regimens based on histology and targeted agents for patients who carry somatic activated oncogenes, such as epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and translocated anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK). Majority of patients do not attain prolonged disease control, and 5-year survival rates remain low3. Increasing evidence has shown a relationship between PDL1 expression and genetic alterations in oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. For instance, deletion of PTEN leads to PDL1 up-regulation in lung squamous cell carcinoma4. Moreover, patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC may be susceptible to PD-1 blockade immunotherapy5. EGFR-mutant lung tumors inhibit antitumor immunity by activating the PD-1/PDL1 pathway to suppress T-cell function and increase levels of proinflammatory cytokines; exposure to EGFR-TKIs leads to PD-L1 downregulation5. An anti-PD-1 antibody significantly reduces tumor growth and prolongs the survival of mice with EGFR-mutant adenocarcinoma5. Other oncogene-activated models may similarly drive immune escape.

A recent study in the British Journal of Cancer has reconfirmed that PD-L1 expression is correlated with EGFR mutations6. D’Incecco et al.6examined PD-1 and PD-L1 expression via immunohistochemistry in a cohort of 125 NSCLC patients, 30 of whom where “triple negative” (wild-type EGFR, ALK, and KRAS) and the other 95 were EGFR-mutant, KRAS-mutant, or ALK translocated. All cases with moderate (+2) or strong staining (+3) in more than 5% of tumor cells6were regarded as PD-1 or PD-L1 positive. The investigators identified different clinical and biological profiles of patients according to PD-1 and PD-L1 expression6. Patients with PD-1 positive tumors tended to be male and/or smokers with KRAS-mutant adenocarcinoma. By contrast, patients with PD-L1 positive tumors were morelikely to be female and/or never or former smokers with EGFR-mutant or ALK-translocated adenocarcinoma histology6.

Until now, the results of the correlation between PD-1/ PD-L1 expression and EGFR mutations remain controversial. Gettinger et al.7reported that EGFR or KRAS mutations did not correlate with response rate to nivolumab for NSCLC patients. Some researchers found that activation of the EGFR pathway induced PD-L1 expression to help NSCLC tumors evade the antitumor immune response5,8. Mu et al.9did not observe a significant correlation between PD-L1 expression and EGFR, KRAS, BRAF, or ALK status in stage I NSCLC patients. Similarly, Zhang et al.10found no significant relationship between PDL1 expression and mutational status of EGFR or KRAS in lung adenocarcinoma. Most recently, Ansen et al.11reported that PDL1 expression was associated with distinct genotypes of EGFR, KRAS, and STK11 in the two most common histological NSCLC subtypes (i.e., adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma) in the 2014 ASCO Annual Meeting.

D’Incecco et al.6observed that PD-1 positive status was significantly associated with the presence of KRAS mutations, whereas PD-L1 positive status was significantly associated with presence of EGFR mutations. Recent data presented by Rizvi et al.12demonstrate that neoantigens created by nonsynonymous mutations may underlie the activity of PD-1 inhibition in NSCLC, that nonsynonymous mutation burden may be a predictive biomarker of response to anti-PD-1 therapy, and that immunotherapy may be beneficial for smoking-associated lung cancers. Pembrolizumab was more efficient in patients with a smoking-associated mutational signature (transversionhigh tumors), which correlated with nonsynonymous mutation burden and a higher quantity of putative neoantigens12. Patients with a durable clinical response had a higher neoantigen burden than those without, suggesting that T-cell responses to neoantigens created by somatic mutations may underlie pembrolizumab activity in NSCLC12.

Besides smoking-related changes, the researchers were also able to identify other mutations present in lung cancer that may contribute to a high mutation burden and response to PD-1 inhibition. Specifically, they noted deleterious mutations in DNA repair and replication genes that have high mutation burden response and high response to pembrolizumab, such as POLD1, POLE, and MSH2. Some of these mutations occur in neversmokers with high mutational burden; this finding may explain why some never-smokers may also respond to therapy with PD-1 inhibitors12.

D’Incecco et al.6found that patients with PD-L1 positive expression had higher sensitivity to EGFR-TKIs, longer time to progression (TTP), and better overall survival than PD-1 negative patients. Among 95 patients treated with gefitinib or erlotinib, sensitivity to TKIs was significantly correlated with PD-L1 expression, whereas tumor PD-1 expression did not seem significant in terms of response rate, TTP, and survival. Furthermore, among the 54 EGFR-mutant patients, TTP to EGFR TKI was significantly longer in PD-L1 positive than negative tumors6. Although PD-L1 is regarded as an immunosuppressive molecule, its expression is not necessarily synonymous with tumor immune evasion and may reflect an ongoing antitumor immune response that includes production of IFN-γ and other inflammatory factors. This finding is consistent with retrospective studies in NSCLC, where tumor PD-L1 expression has been shown to be a positive prognostic factor. Currently, the feasibility of PD-L1 expression level as a prognostic index has not been confirmed. Retrospective analysis has shown that overexpression of PD-L1 in NSCLC cells indicates high invasiveness and poor prognosis: Yang et al.13reported that pulmonary adenocarcinoma patients with high expression of PD-L1 had longer recurrence-free survival than those with low expression of PD-L1. Velcheti et al.14showed that patients with PD-L1 protein or mRNA overexpression had longer total survival not correlated with age, staging, or tissue type compared with patients with PD-L1 protein or mRNA under-expression.

D’Incecco et al.6described PD-1 expression on tumor cells for the first time. Until now, the evidence points to PD-L1 being commonly up-regulated in NSCLC and PD-1 being expressed on the majority of TILs. This result explains the development of monoclonal antibodies against PD-L1 or PD-1. However, the authors did not examine PD-1 expression on CD8+TILs or explore any correlation that may exist between PD-1-positive TILs and expression of PD-L1 on cancer cells.

A suitable test should be created to measure PD-L1 expression levels with established thresholds that can be used as a biomarker for anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapies. A multitude of questions pertaining to companion predictive biomarkers to anti-PD-1/anti-PD-L1 therapies remain unanswered: Which PD-L1 antibody most accurately and reproducibly measures PD-L1 protein expression and predicts response to therapy? Which cutoff should be utilized to determine PD-L1 positivity/ negativity? Should PD-L1 protein be measured in the tumor epithelium, stroma, or both? Should a different measure of PDL1 expression, such as quantitative immunofluorescence or RNA, be used instead of standard immunohistochemistry protein methodology? Which additional components, such as TILs, PD-1, or PD-L2, play a role in predicting response? Currently, the various assays tend to be propriety to each of the groups developing the antibodies. Most assays examine PD-L1 stainingon the tumor. Based on recent data from Herbst et al.15, some assays observe PD-L1 staining on immune infiltrate, including tumor and immune cells and the entire microenvironment. To date, we still do not know what antibodies will emerge or what the final cutoffs will be for a valid test measuring PD-L1 expression levels. Instead of using binary cutoffs to determine positivity/negativity, some researchers, including D’Incecco et al.6, have investigated quantitative measurements of PD-L1 expression. Quantitative measurement has proven difficult due to the apparent heterogeneity of PD-L1 expression, but whether a more quantifiable assay can better predict the response to anti-PD-1/anti-PD-L1 therapies remains unknown. Multiple companion predictive biomarkers that measure components in the PD-1/PD-L1 axis, TILs, and various stimulatory molecules will be required to predict response to immune therapies. Finally, the data from D’Incecco et al. suggest that EGFR-mutant NSCLC is highly eligible for PD-1/PD-L1 immunotherapy, and PD-L1 may represent a favorable biomarker candidate for response to EGFR-TKIs. If this finding is reconfirmed in prospective studies, then immunocheckpoint blockade combination with EGFR TKIs could be a major step forward in improving outcomes of EGFR-mutant NSCLC patients.

Conflict of Interest Statement

No potential conflicts of interest are disclosed.

References

1. Pardoll DM. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2012;12:252-264.

2. Schreiber RD, Old LJ, Smyth MJ. Cancer immunoediting: integrating immunity’s roles in cancer suppression and promotion. Science 2011;331:1565-1570.

3. Pao W, Girard N. New driver mutations in non-small-cell lung cancer. Lancet Oncol 2011;12:175-180.

4. Xu C, Fillmore CM, Koyama S, Wu H, Zhao Y, Chen Z, et al. Loss of Lkb1 and Pten leads to lung squamous cell carcinoma with elevated PD-L1 expression. Cancer Cell 2014;25:590-604.

5. Akbay EA, Koyama S, Carretero J, Altabef A, Tchaicha JH, Christensen CL, et al. Activation of the PD-1 pathway contributes to immune escape in EGFR-driven lung tumors. Cancer Discov 2013;3:1355-1363.

6. D’Incecco A, Andreozzi M, Ludovini V, Rossi E, Capodanno A, Landi L, et al. PD-1 and PD-L1 expression in molecularly selected non-small-cell lung cancer patients. Br J Cancer 2015;112:95-102.

7. Gettinger S, Horn L, Antonia SJ, Spigel DR, Gandhi L, Sequist LV, et al. Efficacy of nivolumab (anti-PD-1; BMS-936558; ONO-4538) in patients with previously treated advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): subpopulation response analysis in a phase 1 trial. Thorac Oncol 2013;8:P2.11-038.

8. Chen N, Fang W, Zhan J, Hong S, Tang Y, Kang S, et al. Upregulation of PD-L1 by EGFR Activation Mediates the Immune Escape in EGFR-driven NSCLC: Implication for Optional Immune Targeted Therapy for NSCLC Patients with EGFR Mutation. J Thorac Oncol 2015. [Epub ahead of print].

9. Mu CY, Huang JA, Chen Y, Chen C, Zhang XG. High expression of PD-L1 in lung cancer may contribute to poor prognosis and tumor cells immune escape through suppressing tumor infiltrating dendritic cells maturation. Med Oncol 2011;28:682-688.

10. Zhang Y, Wang L, Li Y, Pan Y, Wang R, Hu H, et al. Protein expression of programmed death 1 ligand 1 and ligand 2 independently predict poor prognosis in surgically resected lung adenocarcinoma. Onco Targets Ther 2014;7:567-573.

11. Ansen S, Schultheis AM, Hellmich M, Zander T, Brockmann M, Stoelben E, et al. PD-L1 expression and genotype in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). J Clin Oncol 2014;32:abstr 7517.

12. Rizvi NA, Hellmann MD, Snyder A, Kvistborg P, Makarov V, Havel JJ, et al. Cancer immunology. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science 2015;348:124-128.

13. Yang CY, Lin MW, Chang YL, Wu CT, Yang PC. Programmed cell death-ligand 1 expression in surgically resected stage I pulmonary adenocarcinoma and its correlation with driver mutations and clinical outcomes. Eur J Cancer 2014;50:1361-1369.

14. Velcheti V, Schalper KA, Carvajal DE, Anagnostou VK, Syrigos KN, Sznol M, et al. Programmed death ligand-1 expression in nonsmall cell lung cancer. Lab Invest 2014;94:107-116.

15. Herbst RS, Soria JC, Kowanetz M, Fine GD, Hamid O, Gordon MS, et al. Predictive correlates of response to the anti-PD-L1 antibody MPDL3280A in cancer patients. Nature 2014;515:563-567.

Cite this article as: Rosell R, Palmero R. PD-L1 expression associated with better response to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Cancer Biol Med 2015;12:71-73. doi: 10.7497/j.issn.2095-3941.2015.0026

Correspondence to: Rafael Rosell

E-mail: rrosell@iconcologia.net

april 8, 2015; accepted May 4, 2015.

available at www.cancerbiomed.org

Copyright ? 2015 by Cancer Biology & Medicine

Cancer Biology & Medicine

2015年2期

Cancer Biology & Medicine

2015年2期

- Cancer Biology & Medicine的其它文章

- Predictive value of K-ras and PIK3CA in non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with EGFR-TKIs: a systemic review and meta-analysis

- Paclitaxel-etoposide-carboplatin/cisplatin versus etoposidecarboplatin/cisplatin as first-line treatment for combined small-cell lung cancer: a retrospective analysis of 62 cases

- Current approaches in treatment of triple-negative breast cancer

- Changes in tumor-antigen expression profile as human small-cell lung cancers progress

- Assays for predicting and monitoring responses to lung cancer immunotherapy

- Understanding the function and dysfunction of the immune system in lung cancer: the role of immune checkpoints