Electrical stimulation of dog pudendal nerve regulates the excitatory pudendal-to-bladder reflex

Yan-he Ju, Li-min Liao,

1 Department of Urology, China Rehabilitation Research Center, Beijing, China; School of Rahabilitation Medicine, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China

2 Center of Neural Injury and Repair, Beijing Institute for Brain Disorders, Beijing, China

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Electrical stimulation of dog pudendal nerve regulates the excitatory pudendal-to-bladder reflex

Yan-he Ju1,2, Li-min Liao1,2,*

1 Department of Urology, China Rehabilitation Research Center, Beijing, China; School of Rahabilitation Medicine, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China

2 Center of Neural Injury and Repair, Beijing Institute for Brain Disorders, Beijing, China

Graphical Abstract

orcid: 0000-0002-7092-6576 (Li-min Liao)

Pudendal nerve plays an important role in urine storage and voiding. Our hypothesis is that a neuroprosthetic device placed in the pudendal nerve trunk can modulate bladder function after suprasacral spinal cord injury. We had confirmed the inhibitory pudendal-to-bladder reflex by stimulating either the branch or the trunk of the pudendal nerve. This study explored the excitatory pudendal-to-bladder reflex in beagle dogs, with intact or injured spinal cord, by electrical stimulation of the pudendal nerve trunk. The optimal stimulation frequency was approximately 15—25 Hz. This excitatory effect was dependent to some extent on the bladder volume. We conclude that stimulation of the pudendal nerve trunk is a promising method to modulate bladder function.

nerve regeneration; pudendal nerve; neurogenic bladder; spinal cord injury; electrical stimulation; urodynamics; voiding reflex; neuromodulation; neural regeneration

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) commonly causes neurogenic bladder, which seriously affects a patient’s quality of life, and sometimes threatens a patient’s life. Neuromodulation and neurostimulation are promising directions of treatment to rehabilitate the bladder. Many investigators have studied the inhibitory pudendal-to-bladder reflex by stimulating either the branch or the trunk of the pudendal nerve, and these have been successfully applied clinically (Groen et al., 2005; Spinelli et al., 2005; Boggs et al., 2006a). However, the excitatory pudendal-to-bladder reflex has not been well studied in dogs. Some experiments in cats have been done aspre-clinical studies, but there are no reports of any large-sample clinical application (Tai et al., 2006; Yoo and Grill, 2007). Pudendal nerve is the key nerve to control the lower urinary function. It is hypothesized that a neuroprosthetic device placed in the pudendal nerve trunk can control bladder function after suprasacral SCI. This study explores whether or not direct stimulation of the pudendal nerve trunk can elicit detrusor contraction and what the optimal parameters are in beagle dogs with intact and injured spinal cord. We provide an experimental basis for further development of a neuroprosthetic device based on pudendal nerve stimulation.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Four male beagle dogs were provided by the Experimental Animal Center of Capital Medical University in China (license No. SCXK (Jing) 2015-0005). Their average age was 15 months, range 8—20 months; average weight was 14 kg, range 10—18 kg. All protocols involving the use of animals in this study were approved by the Experimental Animal Committee of Capital Medical University in China.

Measurement of bladder function

The dogs were intraperitoneally anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (25 mg/kg) and restrained on an experimental table. Their bladder function was evaluated by cystometry when in anesthetized and conscious states. A 5F double lumen catheter (Cook Company, Spencer, IN, USA) was introduced through the urethra into the bladder. One lumen of the catheter was attached to a pump to infuse the bladder with saline at the rate of 5 mL/min, and the other lumen was connected to a pressure transducer to monitor the bladder pressure. A 12F dual lumen balloon catheter (Cook Urological Inc., Spencer, IN, USA) was inserted into the rectum approximately 10 cm from the anus and was connected to a transducer to monitor the abdominal pressure (Andromeda Urodynamic System, Taufkirchen/Potzham, Germany). Residual volume, after voiding, was measured by withdrawing the fluid through the catheter with a syringe. Bladder capacity was defined as the infused volume at which fluid leaked around the urethral catheter with or without a bladder contraction. Voiding efficiency and peak bladder pressure were used to evaluate the effectiveness of bladder contraction induced by filling or stimulation. Voiding efficiency was defined as the total voided volume divided by the total infused volume.

Pudendal nerve stimulation

The left pudendal nerve was accessed posteriorly between the sciatic notch and the tail. The right pudendal nerve was kept intact. A tripolar cuff electrode (NC223, Micro Probe, Inc, Gaithersburgh, MD, USA) was wrapped around the pudendal nerve at a location central to the deep perineal branch. After placement of the cuff electrodes, the leads were connected to a Grass S88 stimulator and stimulus isolator (Grass Medical Instruments, Natus Neurology Inc., Warwick, RI, USA). Uniphasic pulses (pulse width 0.2 ms) at different frequencies (0.5—50 Hz) were used to stimulate the pudendal nerve at an intensity determined by preliminary test. The actual intensity varied between dogs, within a range of 1—4 V. We can observe visible anal and tail contraction at these intensities without causing discomfort to the dogs. Pudendal nerve stimulation was applied at different bladder volumes. Multiple cystometrograms were performed in each dog. Parameters measured from multiple trials in the same dog were averaged.

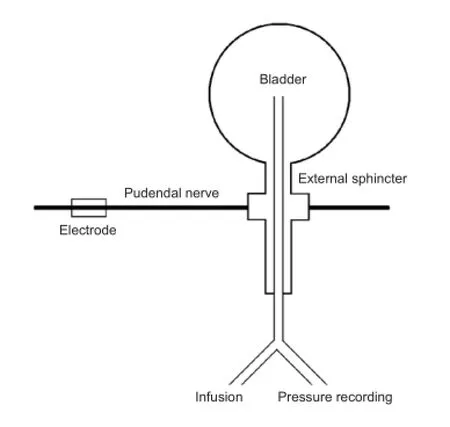

The spinal cord was transected at the T9—10vertebral level by a dorsal laminectomy under aseptic conditions. After full recovery from anesthesia, the dog was returned to the cage. The bladder was manually catheterized three to four times a day to prevent bladder over-distension and infection. Cystometry was repeated at different stages of SCI until stable reflex voiding was established. Approximately 3—4 weeks after spinal cord transection, spinal micturition reflexes in response to bladder distension or tactile stimulation of the perigenital region were prominent. The bladder function of SCI dogs was re-evaluated in anesthetized and conscious states. The excitatory pudendal-to-bladder reflex in SCI dogs was explored by electrical stimulation of the pudendal nerve trunk. The schematic diagram is shown in Figure 1.

Results

Effect of anesthetics on micturition in dogs with intact spinal cord

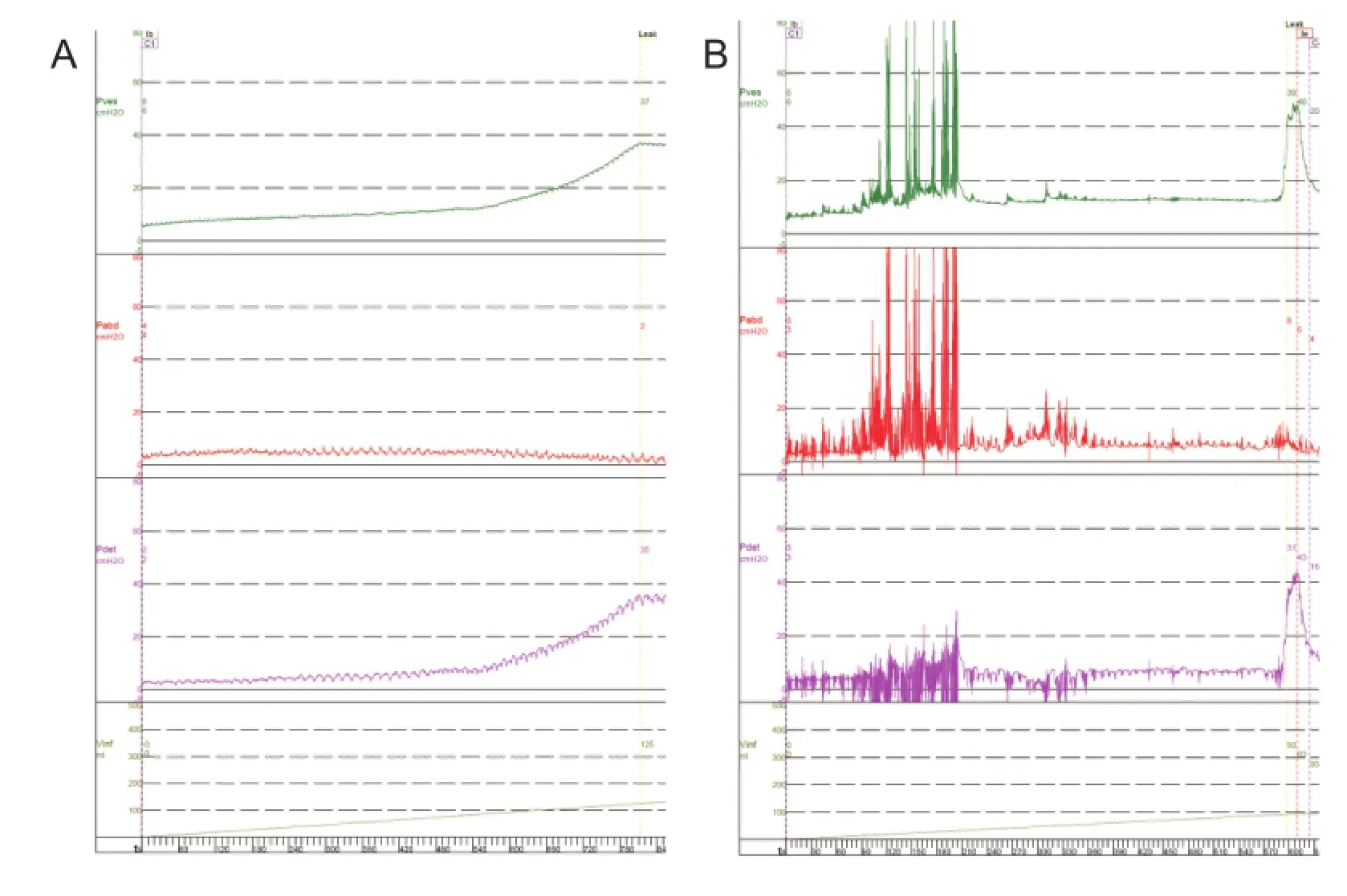

Anesthetics (pentobarbital sodium 25 mg/kg) had a significant effect on micturition. Under anesthesia, the dog manifested continuous urinary retention and high pressure in the bladder accompanied by overflow leakage of fluid from the meatus (Figure 2A). When the dog was resuscitated, a normal micturition reflex was found. At the end of a cystometrogram, bursting voiding pattern occurred and the voiding was very efficient with little residual urine in the bladder (Figure 2B).

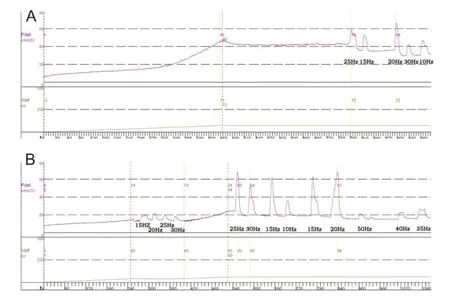

Under anesthesia, the pudendal nerve trunk was electrically stimulated during a cystometrogram. Results showed that stimulation could induce detrusor contraction (excitatory pudendal-to-bladder reflex) at a volume larger than 40% capacity, and as the volume increased, the amplitude of induced detrusor contraction increased. At a given volume, 15—25-Hz stimulation induced the highest detrusor contraction compared with other stimulation frequencies (Figure 3). With stimulation at volumes below 40% capacity, the bladder was continuously inactive even using different stimulation parameters (Table 1).

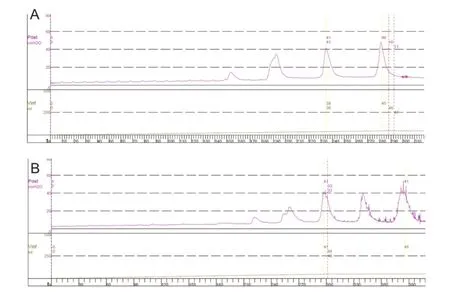

Anesthetics effect on micturition in SCI dogs

In SCI dogs, pentobarbital anesthesia had little effect on urodynamic pattern and parameters (Figure 4). The voiding induced by bladder distension was very inefficient. When the bladder was filled at the rate of 5 mL/min, several reflex bladder contractions appeared first, but no voiding was observed. These initial reflex bladder contractions were defined as non-voiding contractions. When the bladder volume increased, a reflex bladder contraction was defined as a voiding contraction, which could elicit the release of saline aroundthe urethral catheter, and this volume was defined as the bladder capacity.

Figure 2 Cystometrogram in a dog with intact spinal cord.

Figure 3 Pudendal nerve stimulation in a dog with intact spinal cord, in the anesthetized state.

Figure 1 Schematic diagram of the experiment.

Repeated tests in four SCI dogs revealed a consistent detrusor over activity and low voiding efficiency with large residual volume, though the bladder capacity of each dog varied considerably (Table 1).

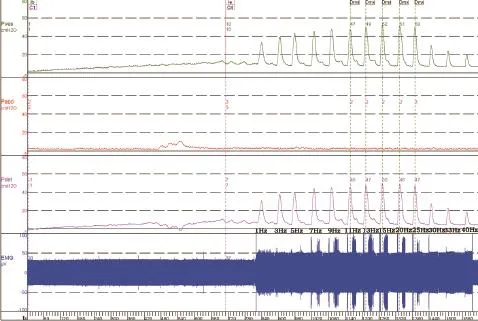

Voiding induced by pudendal nerve stimulation in SCI dogs at the bladder capacity

As exhibited in Figure 5, during slow infusion of saline, the bladder started rhythmic contractions with the amplitude gradually increasing until a voiding contraction appeared. When the infusion was stopped, 120 mL of saline had been infused into the bladder. Pudendal nerve stimulation at different frequencies (0.5—50 Hz) was then tested at the capacityduring the rhythmic detrusor contractions. The stimulation intensity was determined by a preliminary test. At this stimulation intensity, anal sphincter contractions were clearly observable. Stimulation excited the bladder by increasing the amplitude and duration of the contractions more than those induced by bladder distension.

Figure 4 Cystometrogram in a dog with spinal cord injury (the same dog as Figure 2).

Figure 5 Effect of pudendal nerve stimulation at different frequencies on bladder contraction during rhythmic detrusor contractions in a dog with spinal cord injury.

Figure 6 Cystometrogram of a dog with spinal cord injury (the same dog as Figure 5) with stimulation at 30% capacity.

Table 1 Measurements for each dog under different experimental conditions*

Changes induced by pudendal nerve stimulation in SCI dogs at a volume of 30% capacity

When the infusion was stopped at a volume of 30% capacity (Figure 6), the bladder was inactive in the absence of stimulation. Stimulation at frequencies 1—40 Hz could elicit the bladder contraction, with the highest detrusor pressure (50 cmH2O) obtained at 15—20 Hz.

Discussion

It is well known that most anesthetics interfere with the micturition. In our study in which recovery from anesthesia was required, we chose pentobarbital sodium as the anesthetic because of its established long-lasting stable anesthetic level and low toxicity for recovery. Our study indicated that pentobarbital sodium had a significant effect on the micturition in dogs with intact spinal cord but little influence in SCI dogs. Thus, we consider that the micturition study under anesthesia was almost the same as that in conscious SCI dogs. The site of action by pentobarbital is mainly the reticular formation of the brain stem and higher centers. However, in SCI dogs, the connection between brain stem and primary sacral center is interrupted, thus phenobarbital has little additional effect on micturition in SCI dogs.

The excitatory perineal-to-bladder reflex, which exists in neonatal kittens, can be activated by their mother licking the perineal area to induce voiding (De Groat, 1975). This excitatory reflex is suppressed in later development. In adult animals with an intact spinal cord, micturition is mediated by a spino-bulbo-spinal reflex involving the pontine micturition center. The pontine micturition center coordinates the activity of the bladder and the urethra, so that during storage the bladder is quiescent and the urethra is closed. Whereas the bladder contracts and the urethra relaxes during voiding, after SCI, this coordination is lost due to the absence of supraspinal control. The spinal reflexes of the lower urinary tract undergo significant plasticity (de Groat et al., 1993). Reflex micturition is mainly triggered by C-fiber afferents in the pelvic nerve (de Groat et al., 1990, 1998) instead of Aδ fibers. This spinal reflex results in frequent bladder contractions during storage, inefficient voiding and a large residual bladder volume (Burns et al., 2001; Jamil, 2001).The leakage of urine will reduce tension in the bladder wall, and, in turn, reduce the excitatory input to the bladder-to-bladder spinal reflex pathway. Therefore, only small, short-lasting bladder contractions and release of saline from the bladder occurred. The excitatory perineal-to-bladder reflex also reappears. Mechanical stimulation of the perigenital area in SCI cats induced bladder contractions, while direct pudendal nerve stimulation in cats induced bladder contractions (Tai et al., 2007a). The plasticity underlying the pudendal-to-bladder reflex after chronic SCIcould involve at least two mechanisms. One possibility is that during postnatal development, the tonic descending inhibitory influence from the brain turns off the primitive excitatory reflex circuitry in the spinal cord. Interruption of these descending connections in older animals then causes the re-emergence of the neonatal reflex pattern. A second possibility is that, during postnatal development, elimination of primary afferent terminations in the spinal cord or pruning of excitatory interneuronal inputs to bladder parasympathetic preganglionic neurons is responsible for postnatal loss of reflexes. Whereas following SCI, restoration of synaptic connections leads to the recovery of the neonatal reflexes (Tai et al., 2011). The same is shown in the present study on dogs with intact spinal cord and SCI. The excitatory response is frequency- and volume-dependent. The optimal stimulation frequency is 15—25 Hz. At larger bladder volume, the bladder contraction is more easily elicited and has larger amplitude.

Our study was a prospective survival experiment, so the bilateral ureters were not ligated, which might have some influence on the accuracy of bladder volume determination. The voiding efficiency of SCI dogs in our study was lower compared with other reports (Boggs et al., 2006b; Tai et al., 2007a). We consider that the urethral catheter might have a certain effect on voiding due to direct mechanical obstruction or sphincter-to-sphincter reflex action, which aggravates the already present detrusor-sphincter-dyssynergia. It would be preferable to use a suprapubic cystostomy for infusion and pressure recording. However, in dogs with intact spinal cord, the urethral catheter had little effect on voiding. Thus, we considered the main cause of low voiding efficiency was detrusor-sphincter-dyssynergia as a consequence of SCI. Different voiding pattern in different species might be another reason that dogs have a bursting pattern while cats have a continuous pattern. In our study, we applied continuous mid-frequency stimulation, which was a different procedure from those in previous reports (Boggs et al., 2006b; Tai et al., 2007a). Intermittent, short-burst stimulation of the pudendal nerve might improve voiding efficiency further. Another measure to improve voiding efficiency might be combined with high-frequency blocking of the pudendal nerve (Tai et al., 2007b). Selective stimulation of the secondary branches of the pudendal nerve may be an alternate means to improve voiding efficiency (Yoo et al., 2008; Bruns et al., 2009).

In summary, there is an excitatory pudendal-to-bladder reflex in dogs. Large bladder contractions could be induced by direct electrical stimulation of the pudendal nerve trunk. The development of treatment based on this would have valuable clinical applications. It may contribute to a new voiding mode in SCI patients. Yet it will be necessary to improve the voiding efficiency before it is applied clinically.

Author contributions: YHJ was the main contributor to experiment completion, and LML was the experiment designer. Both authors approved the final version of the paper.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Plagiarism check: This paper was screened twice using Cross-Check to verify originality before publication.

Peer review: This paper was double-blinded and stringently reviewed by international expert reviewers.

Boggs JW, Wenzel BJ, Gustafson KJ, Grill WM (2006a) Frequency-dependent selection of reflexes by pudendal afferents in the cat. J Physiol 577:115-126.

Boggs JW, Wenzel BJ, Gustafson KJ, Grill WM (2006b) Bladder emptying by intermittent electrical stimulation of the pudendal nerve. J Neural Eng 3:43-51.

Bruns TM, Bhadra N, Gustafson KJ (2009) Intraurethral stimulation for reflex bladder activation depends on stimulation pattern and location. Neurourol Urodynam 28:561-566.

Burns AS, Rivas DA, Ditunno JF (2001) The management of neurogenic bladder and sexual dysfunction after spinal cord injury. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 26:S129-136.

De Groat WC (1975) Nervous control of the urinary bladder of the cat. Brain Res 87:201-211.

de Groat WC, Booth AM, Yoshimura N (1993) Neurophysiology of micturition and its modification in animal models of human disease. In: The autonomic nervous system, nervous control of the urogenital system (Maggi CA, ed). London: Harwood Academic Publishers.

de Groat WC, Kawatani M, Hisamitsu T, Cheng CL, Ma CP, Thor K, Steers W, Roppolo JR (1990) Mechanisms underlying the recovery of urinary bladder function following spinal cord injury. J Auton Nerv Syst 30 Suppl:S71-77.

de Groat WC, Araki I, Vizzard MA, Yoshiyama M, Yoshimura N, Sugaya K, Tai C, Roppolo JR (1998) Developmental and injury induced plasticity in the micturition reflex pathway. Behav Brain Res 92:127-140.

Groen J, Amiel C, Bosch JL (2005) Chronic pudendal nerve neuromodulation in women with idiopathic refractory detrusor overactivity incontinence: Results of a pilot study with a novel minimally invasive implantable mini-stimulator. Neurourol Urodynam 24:226-230.

Jamil F (2001) Towards a catheter free status in neurogenic bladder dysfunction: a review of bladder management options in spinal cord injury (SCI). Spinal Cord 39:355-361.

Spinelli M, Malaguti S, Giardiello G, Lazzeri M, Tarantola J, Hombergh UV (2005) A new minimally invasive procedure for pudendal nerve stimulation to treat neurogenic bladder: Description of the method and preliminary data. Neurourol Urodynam 24:305-309.

Tai C, Smerin SE, de Groat WC, Roppolo JR (2006) Pudendal-to-bladder reflex in chronic spinal-cord-injured cats. Exp Neurol 197:225-234.

Tai C, Wang J, Wang X, de Groat WC, Roppolo JR (2007a) Bladder inhibition or voiding induced by pudendal nerve stimulation in chronic spinal cord injured cats. Neurourol Urodynam 26:570-577.

Tai C, Wang J, Wang X, Roppolo JR, de Groat WC (2007b) Voiding reflex in chronic spinal cord injured cats induced by stimulating and blocking pudendal nerves. Neurourol Urodynam 26:879.

Tai C, Chen M, Shen B, Wang J, Liu H, Roppolo JR, de Groat WC (2011) Plasticity of urinary bladder reflexes evoked by stimulation of pudendal afferent nerves after chronic spinal cord injury in cats. Exp Neurol 228:109-117.

Yoo PB, Grill WM (2007) Minimally-invasive electrical stimulation of the pudendal nerve: a pre-clinical study for neural control of the lower urinary tract. Neurourol Urodynam 26:562-569.

Yoo PB, Woock JP, Grill WM (2008) Bladder activation by selective stimulation of pudendal nerve afferents in the cat. Exp Neurol 212: 218-225.

Copyedited by Dawes DA, Stow A, Yu J, Qiu Y, Li CH, Song LP, Zhao M

10.4103/1673-5374.180757 http://www.nrronline.org/

How to cite this article: Ju YH, Liao LM (2016) Electrical stimulation of dog pudendal nerve regulates the excitatory pudendal-to-bladder reflex. Neural Regen Res 11(4):676-681.

Funding: This study was supported by the Capital Medical Development Research Fund of China, No. 2014-2-4141.

Accepted: 2015-09-11

*Correspondence to: Li-min Liao, M.D., Ph.D., lmliao@263.net.

- 中國神經再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- Gait deterioration due to neural degeneration of the corticoreticular pathway: a case report

- Complement components of nerve regeneration conditioned fluid influence the microenvironment of nerve regeneration

- Supplementary motor area deactivation impacts the recovery of hand function from severe peripheral nerve injury

- Combined use of Y-tube conduits with human umbilical cord stem cells for repairing nerve bifurcation defects

- Senegenin inhibits neuronal apoptosis after spinal cord contusion injury

- Human umbilical cord blood-derived stem cells and brain-derived neurotrophic factor protect injured optic nerve: viscoelasticity characterization