A Glimpse of Music and Literature in French Symbolism Through Three Modern Chinese Writers—Shen Congwen, Xu Zhimo, and Liang Zongdai

Qianwei He

Soochow University, China

A Glimpse of Music and Literature in French Symbolism Through Three Modern Chinese Writers—Shen Congwen, Xu Zhimo, and Liang Zongdai

Qianwei He

Soochow University, China

The relationship between music and literature is a continuous topic among poets, and a key subject for the Symbolists. From the mid-19th century on, the French Symbolist theories on music, which largely regard music as the superior form of art, have influenced the modern ideology of both the literary and artistic worlds. French Symbolists have even been considered the pioneers of literary Modernism. Undoubtedly, French Symbolism came into China along with other literary trends during the early 20th century and influenced modern Chinese literature. Modern Chinese writers, in turn, developed their own thinking on music and literature, a thinking which reflected its French roots. Therefore, an examination of their ideas can offer a viewpoint for us to understand the diverse routes of the importation of ideas into China. This article will read into the words of three distinctive modern Chinese writers, to have a glimpse of how they viewed the relationship between music and literature, as well as the inter-relationship between their ideas and the connection with French Symbolism.

music, French Symbolism, Shen Congwen, Xu Zhimo, Liang Zongdai

The close tie between music and literature has always been a focal point in examining literature around the world and throughout time. In the history of Western literature, the dynamics between the two arts became a much-discussed topic among the artists in the nineteenth century. Such discussion lasted through generations of modern artists, especially among the French Symbolists. According to Daniel Albright, “at the dawn of the twentieth century, music became the vanguard medium of the Modernist aesthetics”(Albright, 2004, p. 1). The May Fourth Movement marked the beginning of modern Chinese literature; it was a political movement initiated by university students in Beijing on May 4th, 1919, which in a broader sense belonged to the New Cultural Movement led by Chinese intellectuals from the mid 1910s to the 1920s. After The May Fourth, many Western literary ideas were introduced to China, and the clash between different literary ideas generated debate among Chinese writers. The question of whether music was the best medium among all arts also initiated heated debates among writers, mostly poets. This put forward the debate on whether basic musicality, which refers to the sense of rhythm and rhyme of poetry, is necessary for modern poetry. It also, and in fact most importantly, put forward a broader question of what the best way is to pursue the abstract concept of beauty in arts, which is also one of the main issues that French Symbolism is concerned with. When “music” is discussed in this article, unless otherwise noted, it refers to the concept of music or music in the abstract, rather than audible music (for example, a particular piece of musical work), or the traditional musicality of literature—rhythm and rhyme.

Symbolism, dating from as early as the mid-19th century and concentrated in 1890s Paris, “marks the turn from Romanticism to Modernism” (Bullock & Stallybrass, 1977). It was largely led by a generation of French poets such as Charles Baudelaire (1821 – 1867), Stéphane Mallarmé (1842 – 1898), and Paul Valéry (1871 – 1945). Symbolism, or rather the concept of symbols, has long existed in literature, referring to a form of expression that tries to reach an unseen reality (Symons, 1919). However, the Symbolist movement we define today have theories beyond the traditional uses of symbols; it is a literary movement that is “conscious of itself, in a sense in which it was unconscious”(Ibid., p. 3). While the Romanticists take individual experience as reality, the Symbolists use symbols to approach the idea that “everything in humanity may have begun before the world”; they are concerned with “the soul of things” (Ibid., pp. 8-9). In the process of this pursuit, the Symbolists regard “the indefiniteness of music” as one of “the principal aims”, which is produced by swaying between the imaginary and the real, as well as “a confusion between the perceptions of the different senses” (Wilson, 1931, p. 13).

In the West, the relationship between music and literature is being studied systematically. For example, the Forum of the International Association for Word and Music Studies, established in 2009, offers a platform for scholars to discuss various issues relating to music and literature, and to develop new theories in the related fields. Western literary criticism also has a long history of discussing musical aesthetics and its connection with literature, going back to Eduard Hanslick’sThe Beautiful in Music(1891), which almost provides Modern writers with a fundamental theory of musical aesthetics. In terms of music in modern literature, and Symbolism, there are also several systematic works, such as Albright’sModernism and Music(2004) and Acquisto’sFrench Symbolist Poetry and the Idea of Music(2006). Peter Dayan, the first professor in Word and Music Studies, has also discussed the idea of soundless music. He brings forward the idea of“interart” inArt as Music,Music as Poetry,Poetry as Art,fromWhistler to Stravinskyand Beyond, which sublimates the dialogue between different arts (Dayan, 2011). Without a doubt, music, as an international art, has been explored by Chinese writers, and after the May Fourth Movement, the tendencies of Symbolism and Modernism appeared in modern Chinese literature. There exist studies on individual writers on music, but a systematic study on this topic is completely missing.

Among the three writers this article will focus on, most critical works recognise Xu Zhimo (1879 – 1931) as a Romantic writer, thus overlooking his possible connection with Symbolism in terms of music. There are a number of works on Liang Zongdai (1903 – 1983), and French Symbolism as the influence is obvious, but there lacks a major work that studies Liang’s Symbolist ideas from the perspective of music, let alone abstract music. As for Shen Congwen (1902 – 1988), scholars are gradually noticing his Symbolist tendency. Among them, Liu Hongtao explores it the most inShen Congwen’s Fiction and Modernism(《沈從文小說與現(xiàn)代主義》) (2009), but he also fails to explore deeper the primary subject of Symbolism—music. Furthermore, while scholars are aware of Xu’s mentorship with Shen, seldom do people realise that Liang might have a crucial influence on Shen’s aesthetics. The following pages will take a look at the ideas of music and literature of the three writers and their interrelations with each other and French Symbolism.

Xu Zhimo and Liang Zongdai both had a Western educational background, where Xu’s literary background was usually considered “Anglo-American” and Romantic, while Liang’s bore a strong French Symbolist influence. However, Shen Congwen never studied abroad or learned any foreign language. Hence, it is easy to assume that Shen received little Western influence and that, consequently, his works show little resemblance to Western literature. Nevertheless, such assumption is implausible. Firstly, Chinese literature after May Fourth largely involved imitation of foreign, especially Western, literature. Liu Hongtao suggests that modern Chinese literature was synchronous with Western Modernism, and in fact, the Irrationalist theories of Bergson, Nietzsche, Schopenhauer, and Freud were widely known in China, while Symbolism, Expressionism, Futurism, and the stream of consciousness technique were brought into China and influenced Chinese writers (H. Liu, 2010). Secondly, even though Shen was, in every aspect, a native Chinese writer, he stayed close to the Chinese writers who had strong Western connections. When Shen started his career, he received help and advice from established writers like Xu Zhimo. As the chief editor of the supplementMorning Post(《晨報(bào)副刊》), in which Shen published many of his early works, Xu encouraged Shen and invited him to poetry reading groups from 1925 to 1926 (H. Liu, 2005). Furthermore, from September 1933 onwards, Shen worked as the chief editor of the literary supplementTa Kung Pao(《大公報(bào)?文藝副刊》), and the supplement at the time rather encouraged translations of, and introductions to, foreign literary works (Zhong, 2008). In 1935, after Liang Zongdai came back from Europe, he started to host a page inTa Kung Pao—Poetry Special(《詩(shī)特刊》)—under Shen’s editorship. This special addition toTa Kung Pao’s literary supplement, according to Zhang Jieyu, started a new movement in modern Chinese poetry (Ibid.), and a large andinfluential range of poets were involved. Many poets who published inCrescent Moon(《新月》) andLes Contemporains(《現(xiàn)代》) contributed, including many of the Chinese Symbolists.

It is also a known fact that the Symbolists and their advocates, such as Dai Wangshu, Bian Zhilin, Liang Zongdai, and Feng Zhi, greatly impacted the development of modern Chinese literature, especially poetry. At the same time, Romantic poets like Xu Zhimo also occasionally joined the discussion and translation of Symbolists, such as Charles Baudelaire. In the translation of “Une Chargone”, Xu also provides an introduction to Baudelaire’sLes Fleurs du Mal, and remarks that “I believe that the substrate of the universe, the substrate of human life, the substrate of every visible subject or invisible idea is, and only is, music—splendid music”1(“我深信宇宙的底質(zhì),人生的底質(zhì),一切有形的事物與無形的思想的底質(zhì)——只是音樂,絕妙的音樂。”) (Xu, 1924, p. 6). While Xu also mentions the metrics in Baudelaire, he apparently focuses on Baudelaire’s inner music, or “inaudible music”. Xu claims that “not only can I hear music with sounds, I can also hear music without sounds (it actually has sounds, but you cannot hear them)” (“我不僅會(huì)聽有音的樂,我也會(huì)聽無音的樂(其實(shí)也有音就是你聽不見)。”) (Ibid.). Shen Congwen more than once mentions soundless music, for example, “I am mad. I am mad for abstraction. I see some symbols, a form, a ball of string, a kind of soundless music and a wordless poem” (“我正在發(fā)瘋。為抽象發(fā)瘋。我看到一些符號(hào),一片形,一把線,一種無聲的音樂,無文字的詩(shī)歌。”) (Shen, 2009, Vol. 12, p. 43). What is this soundless music? It is poetry and it is painting, like what Xu describes as “sounds” in Baudelaire’s poetry—“the tone and colour of his poetry is like the blueness reflected in the beams of setting sunlight—distant, bleak, and sinking” (“他詩(shī)的音調(diào)與色彩像是夕陽(yáng)余燼里反射出來的青芒——遼遠(yuǎn)的,慘淡的,往下沉的。”) (Xu, 1924, p. 5).

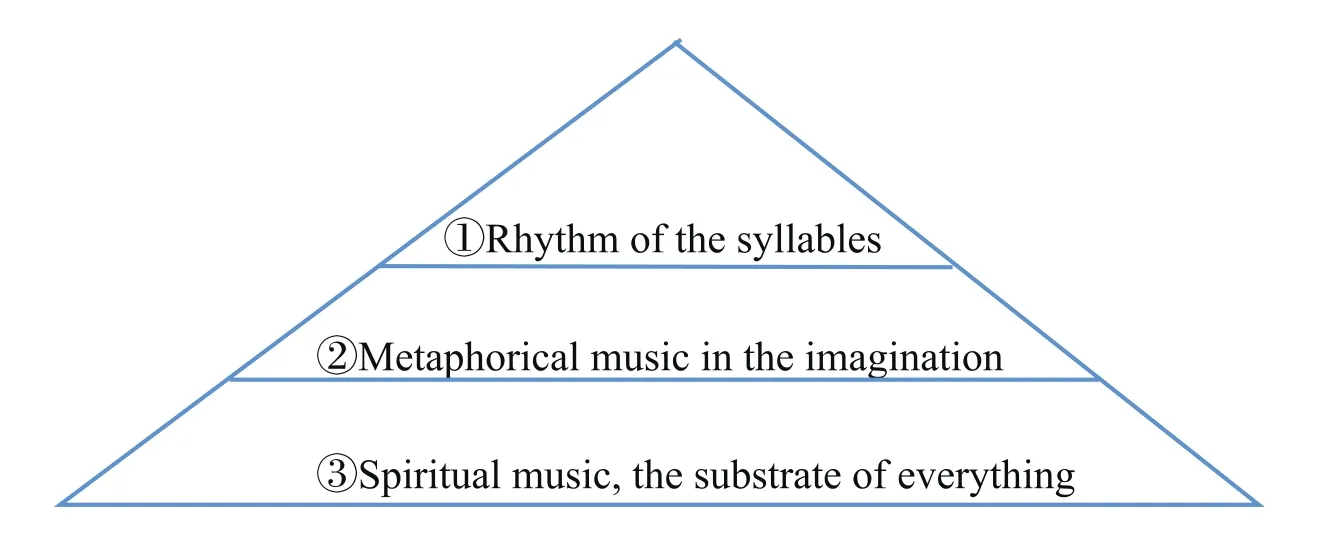

Xu goes on to describe another kind of music in poetry, “imaginary music”: “for music, as long as you listen—the chirps near water, the swallows chatting in between the beams, the sound of water flowing through the valley, the soundwaves of the woods—as long as you have the ears to listen, when you can hear it, ‘hearing’ means ‘understanding’ […] It is all in your imagination” (“但音樂原只要你聽:水邊的蟲叫,梁間的燕語(yǔ),山壑里的水響,松林里的濤聲——都只要你有耳朵聽,你真能聽時(shí),這‘聽’便是‘懂’。[…] 都在你自己的想像里。”) (Ibid., p. 6). Here, while the sound of the words is only referring to the audible sound, there is also a metaphorical music the reader can hear in their imagination. Xu continues to explain that, “therefore, the real essence of the poetry does not live in the words’ literal meaning, but in its subtle, uncatchable syllables; what he (Baudelaire) provokes is not your skin […] but your uncatchable soul—like falling in love—the touching of the lips is only a symbol, what really connects are your souls” (“所以詩(shī)的真妙處不在他的字義里,卻在他的不可捉摸的音節(jié)里;他刺戟著也不是你的皮膚 […] 卻是你自己一樣不可捉摸的魂靈——像戀愛似的,兩對(duì)唇皮的接觸只是一個(gè)象征;真相接觸的,真相結(jié)合的,是你們的魂靈。”) (Ibid.). After Xu published this article, it drew criticism from not only Lu Xun (1924), but also Liu Fu, who sarcastically gave four speculations concerning Xu’s theory: 1) Xu has a microphonein his ears; 2) Xu can hear sounds in the distance; 3) Xu is sensitive to ultrasonic sounds; 4) Xu has something that is not yet invented in his ears that can make sounds for him (F. Liu, 1925). Such criticism only shows that Liu Fu does not understand that hearing here does not mean receiving sounds, but understanding, so the essence of Xu’s imaginary music is not in the sounds at all. Combined with what Xu says at the end of the introduction about the substrate of everything that is music, we can roughly divide what Xu thinks as music into three levels:

①The rhythm of the syllables is the literal sound that can be heard.②This refers to the music the reader of the poem would imagine in his/her mind, according to his/her understanding, completely belonging only to the reader.③The deepest and most profound level of music is the music that flows between the reader and the writer, the substrate of everything, which is soundless, but completely based on something like what Kuriyawaga may have called “universality” (“共通性”).2

As Shen almost considered him to be a mentor, it is very likely that Shen would have gathered thoughts similar to Xu Zhimo’s. As much as Xu cares about the audible musicality in poetry (for example, when Xu introduces Keats’s “Ode to a Nightingale”,3he focuses on both the sound and the meaning beyond it), what he could have passed onto Shen would not have been that kind of musicality; the main argument here is that Shen is much more of a novelist or prose writer than a poet. Shen wrote poems, but in a very small quantity. Most of them are collected and translated folksongs and free verses; only in his later years (post 1949) did he compose poems in traditional Chinese poetic forms. In consequence, what Shen could possibly have learned from Xu Zhimo is potentially exactly what Lu Xun posits mockingly—“everything is music”.

However, Xu Zhimo died early, in 1931, before most texts by Shen that contain such ideas were written. It is most possible that Shen read the Romantic master’s works after his death, but there could also be other influences, one of which is Liang Zongdai.

In a letter in 1951, Shen wrote that seventeen years ago (1934) Ma Sicong, Liang Zongdai, and he, listened to a collection of music by Beethoven and other composers for seven hours in one session (Shen, 2009, Vol. 19, p. 178). In this letter, Shen described Ma learning something about composing, conducting, and instruments, which Liang and Shen did not understand, and Liang having some “l(fā)iterary ideas”.4What kind of literary ideascould those be? Shen himself did not learn anything directly, but only “transferred [it] onto [his] later works, especially a few books and short pieces, in which there existed the rhythmic process of music, which is also closer to some experiments in translating music into something concrete” (Ibid.). It is unlikely that Shen would have been influenced by any theory of composition, or of musical techniques, described by Ma, which he did not understand at the time (as nothing suggests Shen had any professional knowledge of musicology); however, it is quite possible that Liang’s “l(fā)iterary ideas” came through in Shen’s work in the end.

First, how did Liang describe Beethoven?

[What exactly is the melody and tone of Beethoven’sSymphony No.3like? Extremely slow, extremely deep, intermittent, drop by drop, like a deep sigh, like a sobbing, like the heavy sorrowful steps of mourners; no, it is almost like the water dripping from the ancient wall of a bottomless cave, drip by drip, till it touches the deepest part of your heart, and arouses a sad but sacred horrible emotion, which is exactly what Yao Nai would call the art of “yin”;5but it is sublime! It is sublime art!]

貝多芬《第三交響曲》這節(jié)底旋律和音調(diào)究竟是怎樣的呢?緩極了,低沉極了,斷斷續(xù)續(xù)的,點(diǎn)點(diǎn)滴滴的,像長(zhǎng)嘆,像啜泣,像送殯者底沉重而凄遲的步伐,不,簡(jiǎn)直像無底深洞底古壁上的水漏一樣,一滴一滴地滴到你心坎深處,引起一種悲涼而又帶神圣的恐怖心情,正是屬于姚姬傳之所謂 “陰”的藝術(shù);然而sublime呀!究竟不失其為sublime的藝術(shù)呀!(Liang, 2003, Vol. 2, p. 114)

Much like Xu Zhimo’s description of Baudelaire’s poetry, Liang’s appreciation of Beethoven’s music develops through the actual sound—“extremely slow, extremely deep, intermittent, drop by drop”—to the metaphorical music in the listener’s imagination, “l(fā)ike a deep sigh, like a sobbing, like the heavy sorrowful steps of mourners…” If music has any function of description, it only exists in the listener’s mind as metaphorical music. At last, the music goes into one’s heart and one’s soul, having started from the musician’s soul and thus finally making the connection. The connection is spiritually sublime. Therefore, we can observe that this is why Xu Zhimo finds Baudelaire’s poetry musical. This is a subtle and interesting observation, as they share the process of “appreciation”, much as Kuriyawaga illustrates: the appreciation of art is only founded when the unconscious of the author and that of the reader bring about resonance (Kuriyagawa, 2000). Baudelaire’s poetry produces it by the correspondences created by the symbols. The resonance, in Liang’s words, is created by “the water dripping from the ancient wall of a bottomless cave”. It is of course uncertain whether Liang also made such a description to Shen while they were listening to Beethoven together, but it is possible that through Liang, Shen learned how Symbolism sees literature and music.

[When it comes to poetry, music is an absolute condition: if the author does not pay attention to music or does not put any effort into it, if the author’s ears are insensitive, and if, in thecomposition of the poem, rhythm, meter, or music hold no important position which is equivalent to the meaning, then we must have no hope for this man, who wants to sing without feeling the need to and who offers only words that suggest other words.]

Que s’il s’agit d’un poème, la condition musicale est absolue: si l’auteur n’a pas compté avec elle, spéculé sur elle; si l’on observe que son Oreille n’a été que passive, et que les rythmes, les accents et let timbres n’ont pas pris dans la composition du poème une importance substantielle, équivalente à celle du sens, - il faut désespérer de cet homme qui veut chanter sans trop sentir la nécessité de le faire, et tous les mots qu’il offre suggèrent d’autres mots. (Valéry, 2003, Vol. 1, p. 139)

Liang certainly agrees with the necessity for music in poetry, just as he thinks Valéry’s poetry has the most beautiful rhythms. However, the music in poetry has much more significance than metrics to Liang (and perhaps Valéry, too). Although the audible music is important, the actual music is truth. InPoetry and Truth(《詩(shī)與真》), completed in 1934, Liang writes, “truth is the only profound basis of poetry, and poetry is the most supreme and ultimate realisation of truth” (“真是詩(shī)唯一深固的始基,詩(shī)是真底最高與最終的實(shí)現(xiàn)。”) (Liang, 2003, Vol. 2, p. 5). Although, for him, truth is far away and difficult to reach, the joy lies in a poet’s pursuit of truth, just like “the magical beauty of a song is in the process of the ups and downs, and the quickness and slowness of the melody, but not when the tune is finished” (“一首歌底美妙在于音韻底抑揚(yáng)舒卷底程序,而不在于曲終響歇之后。”) (Ibid., p. 6). It follows that a poet is always in the process of approaching truth; there is a form of poetry, like “the ups and downs, the quickness and slowness of the melody”, which contains the truth, or at least, so Liang considers, which still awaits after the tune fades.

To Liang, Valéry is the master of poetry, as he sets out:

[Yet if he is happy only with discovery, but pursues not the expression, or expresses, but not with the skills of an architect or craftsman, the rocking emotion of a musician to build a crystal palace to sing and cry for, he is barely a poet but a mere philosopher. […] The sentiments, the sighs, of common poets are no more than the flowers and weeds that decorate the way to the temple of truth, despite every flower and weed exhibiting to him a deep world; they are but the wood and rock that build the sacred temple, despite every piece of wood and every rock carrying soundless music.]

可是倘若他只安于發(fā)見而不求表現(xiàn),或表現(xiàn)而不能以建筑家意匠的手腕,音樂家震蕩的情緒,來建造一座能歌能泣的水晶宮殿,他還不過是哲學(xué)家而不是詩(shī)人。……

Language and Semiotic Studies

2017年2期

Language and Semiotic Studies

2017年2期

- Language and Semiotic Studies的其它文章

- A Descriptive Study of Howard Goldblatt’s Translation of Red Sorghum With Reference to Translational Norms

- Cultural Unit Green in the Old Testament

- Teaching Syntactic Relations: A Cognitive Semiotic Perspective

- Self-Retranslation as Intralingual Translation: Two Special Cases in the English Translations of San Guo Yan Yi

- Innovation and Integration: Chinese Exegesis and Modern Semantics Before 1949