和馬町訪談

天妮/TIAN Ni

齊軼昳 譯/Translated by QI Yiyi

WA:能否分享一下您對北京歷史街區的整體印象?

和馬町:自從2010年從荷蘭搬到北京以來,我對這個城市中3種不同城市類型共存這一點感觸很深:第一種是歷史悠久的皇城,以胡同巷道和封閉式的院子為代表;第二種是以單位大院為代表的規劃體系;第三種是以超級街區和孤立塔樓為特征的現代化城市。這3種類型的街區我都住過,大約6年前最終選擇定居在北京的歷史街區。對我來說,這里是我感覺最適合本地生活方式和氣候的類型,擁有強烈的地方感和良好的社會凝聚力。 最開始,我在西城區的西海住了幾年,在一個共用的院子里。但3年前我們搬到了東城區北新橋附近的一個私人院子里。

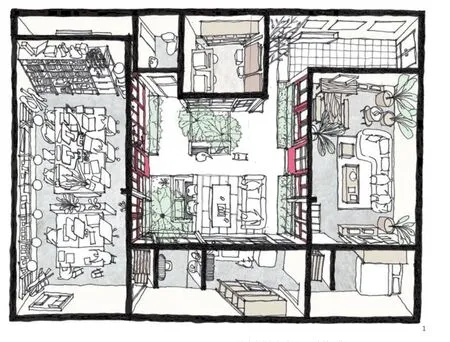

作為一名實踐建筑師,我認為在為自己創造空間的時候應該像為其他人創造一樣,試圖將理論思想與當下現實生活條件相結合。因此選擇在這種類型的空間中生活和工作反應和體現出我們的理念。這個院子很有歷史,在著名的乾隆北京歷史巷道地圖上都有所顯示。在這個基礎上,我們創造了一個現代化的生活和工作空間,但沒有改變歷史悠久的庭院結構(圖1)。我們的庭院位于一個擁有3000多萬人口的大都市的中心,可以看作是現代同質化都市中的綠洲。我們在這次實踐中試圖做的可以被定義為“反思性的區域主義”,它更多的是識別原始條件而不是創造新形式或物件;它是關于技術、社區、當地材料、現代思維和傳統認同感的結合。在現代都市混亂嘈雜的背景下,它可以被看做是一小片自然、和諧與寧靜的存在。

不幸的是,在中國當代的城市發展中,這種觀念似乎已經消失了。經過幾輪土地改革和快速的城市化,以前和諧的體系如今卻是一幅不和諧的景象,城市基礎設施和補丁一樣的城市肌理相混雜。如當前在歷史悠久的北京市中心所見,“傳統的”胡同充滿了違章建設,且伴隨著過度擁擠、基礎設施和衛生條件差等問題。

WA:白塔寺地區的哪些品質吸引了您的注意?在您看來,與其他古老的歷史街區(如什剎海等)相比,白塔寺的特質是什么?

和馬町:上述提到的北京各種城市類型并置的情況統統體現在了白塔寺這一個城市街區內,這使得城市環境變得充滿活力。你可以在這個街區里通過一個僅僅10min步行的路程大致感受到北京的歷史。從古老的被燒毀的寺廟(它帶給街道一些非典型的道路網格)到白塔寺,再到魯迅博物館或者福綏境社會主義大樓生活區,在走過這些地方的同時卻不用經過街區周邊的主干道。 白塔寺地區也相當獨立,例如,它不依賴于外部旅游業。這個街區外部邊緣承擔著與周圍更大范圍城市結構連接的作用,并在該區域的內部保留下了一塊非常本地化的區域。

WA:如何通過微更新的設計方法改善胡同住宅區的環境質量?長期和短期分別用什么方法?

和馬町:我認為不太可能概括地說一個微更新設計方法本身是否成功或如何成功。我認為胡同住宅區重建或“設計更新”沒有標準的解決方案。每個北京胡同地區都有著截然不同的特點,其常住人口結構和當地經濟等都有差異。正確的方法應該是從一個通用的自上而下的模式轉變為自下而上的綜合方式。規劃者在這個過程中只是一個促進者的角色,但關鍵因素還是取決于當地特色、面臨的挑戰和當地居民的想法。此過程也不應該立即產生一個不變的最終結果,而應隨著時間產生動態的空間博弈。因此,不是僅僅強調最終的結果(例如為生活創造一個空間),應該非常強調包含各個利益方的參與式設計過程。我們可以將此定義為從公共空間到市民空間的轉變。在這個空間中,我們和他們之間不再是簡單黑白對立的存在,而是強調集體公民的責任。

1 受訪者在北新橋生活和工作的工作室/ Author's live &work courtyard studio in Beixinqiao(繪圖:呂蕙欣/Drawing by Huixin Loo)

關于最近的胡同住宅再開發,我們可以看到天安門廣場東南方的前門地區改造就是一個很好的例子,解釋了為什么不使用一般的自上而下的手法。幾個世紀以來,前門一直是一個非常公共、熱鬧的地區,就在內城城墻外,但仍然在皇城里。然而,重建計劃是一個自上而下實施的標準方案,純粹是資本驅動、內部決策和權威性的,沒有考慮“通過時間進行空間談判”的方法,也沒有考慮任何“共同設計”的方法。這樣的結果是形成了一層像是貼在混凝土外的歷史化表皮,功能上用作商業設施。根據當時知名國有報紙對此的報道是“外觀大幅改善”,但僅僅是表面的價值。但遺憾的是,這樣的方式進行改造沒有任何傳統價值和持久的功效。在閃閃發光的外立面背后,有價值的內容很少。于是,這個區域在城市的中心變成了一個尷尬的存在,因為正好處在皇城根腳下。在接下來的大柵欄開發中(就在前門地區附近),這種自上而下的、展示/重建類型的歷史街區重建方式被強制執行。相反,這次改建邀請當地社區參與進來,并制定了一個精心策劃的空間模式——即所有被收購的破舊(公共)房屋無論其條件如何都保持不變,并將它們租給精心挑選的新業主。這些業主符合該地區的需求和前景,并且愿意融入胡同生活。

2 白塔寺改造前居住環境/Baitasi local resident conditions before renovation

WA: Can you please share some overall impression of Beijing's historical areas?

Martijn de Geus: Ever since moving to Beijing from Holland in 2010, I have been impressed by the juxtaposition of three distinct urban typologies coexisting within the city; the historic Imperial City with its hutong laneways and enclosed courtyards yuanzi, the planned system with its danwei (Unit)in their "dayuan" (Compound), and the modern city with its superblocks and isolated towers. I've lived in all three typologies; but finally settled in Beijing's historical area about 6 years ago. To me it feels to be the typology most fit for the local lifestyle and climate, with a strong sense of locality and good social cohesion. First, I lived several years around the West Lake in the Xicheng district in a shared yard, but three years ago we moved to a private yard around Beixinqiao in Dongcheng district.

As a practicing architect I believe that you should create a space for yourself as you would want to create for other, to try to integrate theoretical ideas with contemporary real-life conditions, and so the choice to live and work in this type of space is an embodiment of what we stand for. Within the original yard, that can already be seen drawn on the famous Qianlong map of Beijing's historic laneways,we have created a modern living and working space without altering the historic courtyard structure (Fig.1). Situated at the centre of a sprawling metropolis of over more than 30 million people, our courtyard is an oasis from modern urban homogeneity. What we are trying to do in this practice might be described as a re flexive regionalism; it is more about identifying original conditions than inventing original forms or objects. It is about combining technology,community, local materials, modern thinking and a traditional sense of identity. A little piece of nature,harmony and tranquillity against the backdrop of modern urban chaos.

Unfortunately, in recent and contemporary urban development in China, this conception seems to have been lost. Following several rounds of landreforms and rapid urbanization, the previously harmonious system is now more of a giant cacophony of urban infrastructure and patch work structures,as seen in the state of the current historic city centre of Beijing, where "traditional" hutong alley ways are crammed with illegal buildups, overcrowded living conditions, bad infrastructure and poor hygiene.

WA: What kind of qualities of the Baitasi area attracts your attention? In your opinion, compared with other old historical districts (such as Schichahai, etc), what are the unique identity characteristics of Baitasi?

Martijn de Geus: The aformenetioned juxtaposition of various urban typologies in Beijing happens all within one city-scale block in the Baitasi area,which makes for a dynamic urban environment.You can read the history of Beijing at large within a 10-minute walk through just this area. From the ancient burned down temple that left some atypical road network to the laneways, the White Pagoda,the LuXun Museum or the Fusuiqing communist living quarters that towers above it all, while at the same time not even being visible from the main streets surrounding the area. The Baitasi area is also rather independent, it does not rely heavily on outside tourism for its economy for instance. The outer block edges provide a connection with the surrounding larger urban fabric, and leaves a very localised realm on the inside of the area.

WA: How to improve the environmental quality of Hutong's residential area by micro update design approach? How about long-term and short-term?

Martijn de Geus: It is impossible to say if or how a generalized micro update design approach in itself will be successful. And that should be the approach:there is no standard solution to a hutong residential area redevelopment or "design update". Each Beijing hutong area has very different characteristics, with a very different build-up of its resident population, local economy, etc. The right approach should be to change from a one-size- fits-all top-down implementation to a more bottom up, integrated model, in which planners facilitate a process in which local characteristics, local challenges and residents are key. This process should also not have a static outcome that produces an immediate fixed result, but instead should be based on a model of spatial negotiation through time. Thus,rather than (only) de fining the intended outcome, e.g.to produce space for living, there should be a strong emphasis on the participatory design process with various parties involved. We could define this as a move from public to civic space, in which there is no longer a black/white division of tasks between us and them, but instead an emphasis on the collective civic responsibility.

Considering recent hutong residential redevelopment, we can see that the Qianmen-model,an area southeast of Tian'an'men square is a good example of why not to use a general top-down model anymore. For centuries long Qianmen was a very public, lively area just outside the inner-city wall,but still within the lmperial City. The redevelopment plan however was a top-down implemented standard solution, purely capital driven, privatized and full of prestige, without consideration of the"spatial negotiation through time" nor any "codesign methodologies".The result was a historic wallpaper facade over a cleaned up series of concrete supposed-to-be shopping facilities. According to leading state-owned newspapers of the time a"substantial improvement in appearance" , at face value. But, unfortunately not lasting and void of any local signi ficance. Behind the glittery fa?ade makeover there was little substance left. And the area turned out to be a painful embarrassment, right in the centre of the city, under the eyes of the emperor.In the sub sequential Dashilar development, just adjacent to the Qianmen area, a stop on this top down, demo/rebuild type of historic redevelopment was enforced. Instead the local community was involved, and a curated spatial approach was developed, in which all the acquired dilapidated(public) houses remained untouched regardless their conditions, and were rented to carefully selected new owners, who fit the needs and prospects of the area and were willing to blend into hutong life.

在大柵欄的實踐模式獲得認可并成功融入北京國際設計周及其他試點項目之后,該模式被進一步應用于北京城區更為中心和敏感的地區,如白塔寺。從大柵欄的經驗中學習,這一次建立了一個綜合的框架,開發人員和總體規劃師與當地政府、居民、建筑師、學者和學生合作,被稱為“白塔寺再生計劃”。與大柵欄項目的一個重大區別是,白塔寺地區的主要目標不僅僅是引入新角色并隨之高檔化,而是一個社會過程,其中當地居民和基礎設施要在新的外部利益相關者被引入之前得到改善。在我看來,白塔寺項目旨在采取調查性的、參與式的方法,與當地居民合作,評估轉型過程及其對個人、機構、企業和高層次框架下包含政府共同參與的利益相關者的影響。

WA:北京國際設計周和白塔寺地區之間都有哪些雙向影響?

和馬町:首先,整個地區的改造通過該地區作為北京設計周的重要區域,向當地居民以外的公眾進行了良好的傳達。而這反過來可以激發其他自發的自下而上的行動,類似于大柵欄的發展過程。各種例子已經有不少,比如當地的一些咖啡館和創意工作室將工作場所轉移到那里;還有一本叫《LAWAAI》的小雜志,致力于展示白塔寺當地文化的多樣性等等。其次,多方(學術界、市場、居民和政府)參與加快方便了實施的進程,意味著很多研究幾乎可以實時進行。例如,《世界建筑》雜志作為參與的一方可以協助舉辦一系列公共論壇和青年設計師競賽,以便從外部引入新的想法。還有很明智的一點是,在建筑和社會層面,有兩個值得一提的試點項目。這些試點項目在過去的北京國際設計周中已被作為實施策略綜合研究的例子實現和展示。第一個是一個試點民居改造,由來自清華大學的張悅教授領導的設計團隊完成。它旨在通過與當地原住居民的密切合作來促進留住當地居民的改造模式。

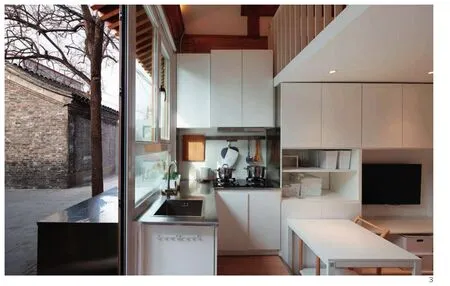

首先一些違建的部分被拆除,然后在里面創建了一個緊湊的多功能儲藏解決方案。另外還增加了一個閣樓層,并在院子里安裝了預制馬桶。 最終打造出兩個家庭單元和一個中央“共享室”,可用于接待客人或休閑活動。為了評估設計意圖的實用性和有效性,其中一個單元目前由開發人員的項目經理使用。另一個居住單元以兩周為輪換周期被提供給該地區的家庭自愿使用。他們可以通過試住來決定是否愿意在自己的家中采用此種方法改造。此外,對于入住后的更多使用情景評估還有待深入研究。

3 改造的“樣板房屋”,有櫥柜配套和儲藏、閣樓解決方案/The renovated "model house", with kitchen arrangement and storage/Loft solution(圖片來源:張悅/Courtesy of ZHANG Yue)

4 由清華學生構設計構思的白塔寺“共享院”/The Baitasi"Sharing Courtyard", conceived by students from Tsinghua University(圖片來源:受訪者/Courtesy of the author)

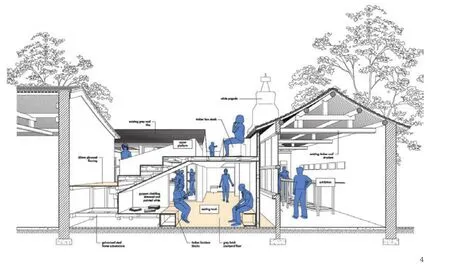

第二個案例側重于改善公共環境,是清華大學國際碩士課程為期8周的城市設計項目的成果。學生們對地段進行了調查和分析,包括對當地居民的采訪。同樣,作為直接測試研究成果的一部分,當地政府分配了一個破舊的庭院用來改造,以檢測學生們的想法。設計的靈感來自于試圖為傳統的胡同體驗帶來全新的視角,讓人們可以從3個層面探索和利用庭院,包括一個安靜的角落、一個天橋和小型圓形劇場。這些新的改造旨在作為附近環境的一個實用的補充設施,而不是一個抽象的獨立存在。新的結構與經過翻新的四合院建立了非常直接的聯系,并打開了前所未有的視角。

5 由清華學生構設計構思的白塔寺“共享院”/The Baitasi"Sharing Courtyard", conceived by students from Tsinghua University(圖片來源:受訪者/Courtesy of the author)

After the successful trial and assessment of the Dashilar efforts, including its integration in the Beijing Design Week and its pilot-projects, this model was also applied in the more central and sensitive Beijing city districts like Baitasi. Learning from Dashilar, this time a comprehensive formal framework was set up where a developer, and master planner, work together with the local governments, residents, architects, academics and students, "Baitasi Remade". A big difference with the Dashilar project, is that the main objective for the Baitasi area is not a mere gentrification with new actors, but foremost a social process in which local residents and facilities are intended to be improved first, before new,outside stakeholders are being brought in. The Baitasi Remade project in my understanding aims to take an investigative, participatory approach, working with local residents to assess processes of transformation and the effect they have on individuals', institutions', corporate and governmental co-participation larger framework of stakeholders.

WA: What are the two-way influence between BJDW and Baitasi?

Martijn de Geus: First of all the transformation of the entire area is well communicated to the general public, outside of the local residents, through the area being one of the key areas for the Beijing Design Week. And this in turn can spark other self initiated bottom-up initiatives, similar to the Dashilar process. Various examples already exist; local cafes,creative studios moving their offices there, a small magazineLAWAAI, dedicated to showing the diversity of Baitasi local culture, etc. Secondly, the combination of various academic, market-driven,residential and government parties means a broad process can be facilitated, in which research can be implemented almost real-time. As suchWAfor instance facilitated a series of public forums and competitions for young architects to bring in fresh ideas from outside. Project wise, on an architectural,social level, there are two realized pilots worth mentioning that were realized and showcased in past BJDW's, as examples of the integrated research to implementation strategy. The first one is a model house, by a design team lead by Prof. ZHANG Yue from Tsinghua Unviersity, aiming to facilitate the retention of local people in close collaboration with the original residents of the plot.

First a series of illegal additions were removed,instead a compact, multifunctional storage solution was created inside, a second loft- floor added, and a prefab toilet united located in the yard. The result is two family units and one central "shared room", that can be used to receive guests or for leisure activities.To assess the practicality and effectiveness of the design intent, one of the units is currently occupied by the project-manager from the developer. The other unit is occupied on a two-week rotational base for families in the area that like to try and see if they would like to have help to adopt this approach in their own homes, a post-occupancy evaluation of a broader scenario that is still to come.

The second example focuses on the improvement of the public environment, and is the result of an 8-week long urban design studio part of the international Master's Program at Tsinghua University, in which students surveyed and analysed the local area, including interviews with local residents.Again, as part of directly testing the research, the local government allocated a dilapidated courtyard for to regenerate, as a test case for the student's ideas. The design was inspired by the opportunity to bring a new perspective to the traditional hutong experience and allow people to explore and utilise the courtyard in three dimensions, including quiet corners, a skywalk and small amphitheatre, and was implemented as a usable addition to the neighbourhood, not as an abstract stand-alone installation. The new structure creates a very direct connection with the renovated courtyard house, and opens up never-before seen perspectives.

注釋/Note

1) CHINA DAILY, Qianmen before and after its renovation, 2011. [2018-06-15]. http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/regional/2011-05/13/content_12508907.htm.