油彩中的變革

老李

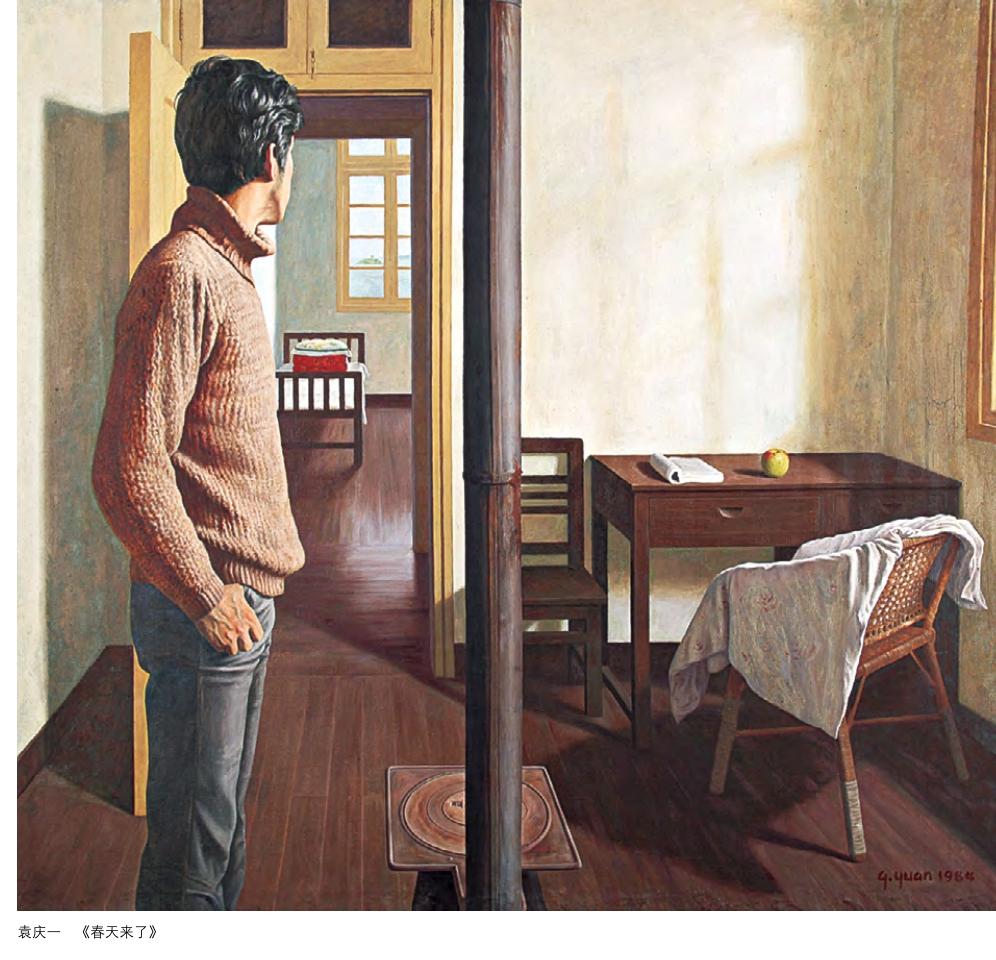

The opening up and reform thoughts spread across China from the end of 1970s and through the whole 1980s, and blew a fresh wind into the art world. Art shook off political topics and returned to the art performance of itself. After a transient popularity of “scar art” after the Cultural Revolution, China entered into a dazzling era of transformation. More people were busy taking in or catching up with the trends pouring in from outside of the country, and were eager to present the diversified new era. It was the start of modernist art in China. Artists turned to emphasize the form of art by taking diverse, innovative, even radical perspectives in creation. On the other hand, realism turned to depict the peaceful and rural countryside. The unprecedented popularity of Luo lizhongs Father proofed that the focus on human itself and humanity was always the core of modern realistic paintings and resonated with the audience.

20世紀70年代末至整個80年代,改革開放的思潮帶動全中國的思想界、藝術界活躍起來。藝術不再依賴于政治,而是逐漸回歸藝術本身;藝術家不用再去表現宏大的命題,而是可以尊崇個人內心的情感,表達自己想要表達的思想。這一時期的油畫創作,反應迅速,表達踴躍,很快便完成了從反思自己向擁抱世界的發展與轉變。

“文革”結束后,中國社會進入一個全面反思的時期,“傷痕”這個關鍵詞開始出現在文學藝術領域。從傷痕文學到傷痕美術,帶著個人化的憂傷表達對社會的反思,人性的、個性的創作讓這些作品具有了真實和感人的力量。

在中國當代油畫發展史上,“傷痕美術”是重要的,卻也是短暫的。因為很快,中國社會便迎來了翻天覆地的變化,進入一個極速發展的時代,外來的新的美術思潮令人應接不暇,一幅多元的畫面重新展現在中國畫家的面前。更多的人根本顧不得憂傷和反思,看向未來、走向世界才是更重要的潮流。當代中國真正的現代主義藝術,從此時正式起步。

1979年,“星星美展”在北京成功舉辦,打破了長期以來藝術界的思想禁錮;85新潮美術運動的掀起,在全國范圍內的年輕藝術家中引發了震動式的反響;1989年在北京舉辦的“中國現代藝術展”,幾乎匯聚了整個80年代的中國現代藝術,并為90年代乃至千禧年之后的中國現代藝術發展奠定了基礎。

西方現代主義早在上世紀初便已傳入中國,只是由于特定的歷史環境而暫時偃旗息鼓。當新的歷史階段甫一來臨,這一藝術的枝丫便迅速成長起來。藝術家們用新奇、多元甚至激進的視角和思維,重新定義中國現代美術。

被貶斥已久的“形式”再度被抬升至與內容幾乎同等重要的位置,影像、行為等多姿多樣的藝術形式紛紛興起,在現代藝術領域,相對“保守”的油畫反而逐漸式微。

在現代主義橫掃藝術界的同時,寫實主義并未在中國終結,反而迎來了一個更加美好的成長期。脫離開政治的束縛,寫實油畫開始回歸到對于現實主義油畫本身的探索之中。畫家們的關注點開始由宏大轉向細微、從熱烈的國家建設轉向平實的鄉土中國。

在寫實中找回對人性、對人本身的關注,是煥然一新的現實主義的油畫的核心之一。在當代中國美術史上,恐怕再沒有一幅油畫作品像羅中立的《父親》那樣流傳之廣,這也恰恰證明了從人本身出發所進行的創作,往往最能夠引起多數人的共鳴。而這是現代主義至今仍做不到的。

- 世界知識畫報·藝術視界的其它文章

- 道金平作品欣賞

- “天民樓”攪動一池春水

- 肖耀彩作品欣賞

- 柏龍華作品欣賞

- 北京匡時春拍穩健收槌

- 誰不逐炎涼