業余時光:非職業樂團在新加坡與曼谷的成功表現

文:司馬勤(Ken Smith) 編譯:李正欣

幾個月前,我在這個專欄里談及了兩種樂團:交響樂團和坐在樂池中的樂團。當時的邏輯顯得很合理,但后來我發現了幾個漏洞。

我所指的,跟卡內基音樂廳前任藝術策劃總監杰里米·格芬(Jeremy Geffen)有一次告訴我的漏洞不一樣。他曾告訴我,自己遵循所有的猶太教規中的飲食規則,“培根除外”。那不是個小“漏洞”,簡直就是模式上的轉變。而我所指的漏洞是一個更簡單的例子,即強調某些概括性或模糊不清的界定因素,故意避開其他的關鍵要點。

維吉爾·湯姆森(Virgil Thomson)是最先提出“兩種樂團”概念的人,他最喜歡在遣詞造句方面一概而論,目的是故意挑戰某些讀者,引起他們的反感。他這樣做也是經過深思熟慮的:他所歸納的兩個門類——“龐大的樂團和直接功能性的樂團”之中,將非職業與學生樂團放在了第二類的最低層次中。

自我從有記憶以來,朋友圈里有不少非職業的音樂家與學生音樂家。要是他們知悉湯姆森的見解,我能猜得到他們的反應——也就是,反感——因此,我故意完全回避了這個話題。不過,上個月我遇上一些非職業音樂家和學生音樂團體。說真的,我要為他們平反,讓他們可以走出“最低層次”的境地。

***

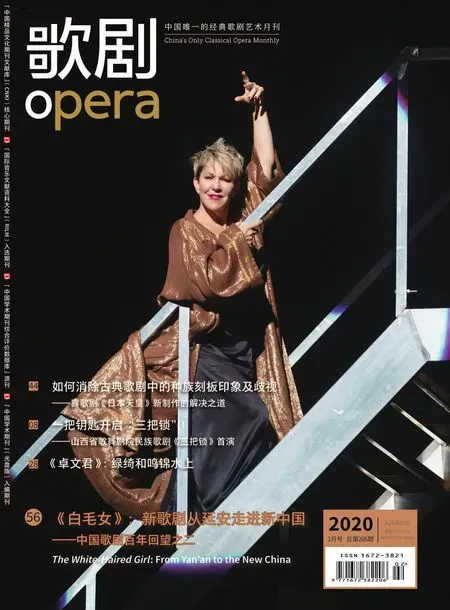

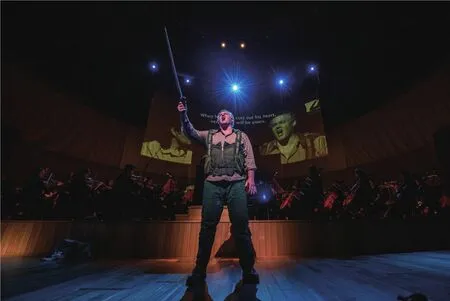

1月初,我人在新加坡,觀看當地制作的《女武神》首演——這不僅是新加坡罕有的瓦格納制作,也很有可能為東南亞地區首套全舞臺版制作的《指環》打響頭炮。讓我在這里正式聲明,這并不是新加坡歌劇團(Singapore Lyric Opera)出品,也不是新加坡交響樂團(Singapore Symphony Orchestra)的制作。把《女武神》搬上舞臺的,是一群非職業的音樂家,他們組織了自己經營的創樂者交響樂團(Orchestra of Music Makers)。

我們再進一步探討:西方歌劇經典中最具挑戰性的作品之一在新加坡上演,而把這部作品付諸實踐卻是一群由醫生、律師與商人組成的團隊。創樂者交響樂團成立于2008年,當時,一群鐘愛音樂的中學生遵從父母的意愿,填報了 “真材實料”的大學專業志愿,畢業后在社會上也紛紛找到“實在的工作崗位”,但他們十分堅決地不放棄音樂。

新加坡創樂者交響樂團制作的《女武神》劇照(攝影:許智勇)

起初,他們甚至不確定自己是否想要舉辦公開演出,可是這些疑慮很快就被打消了。你可以想象,拿到商科與法律學位的人,在求學時期就已經被灌輸了大量的自信,在管理技能方面同樣熟練有加。過了不久,創樂者交響樂團(他們找來了科班出身的專業指揮,還有一位職業樂手當樂團首席)開始在新加坡最顯赫的表演場地——濱海藝術中心,舉行定期音樂會。樂團于2011年錄制了馬勒《第二交響曲(復活)》,音頻被納入新加坡航空公司的機上娛樂系統,更贏得英國《留聲機》(Gramophone

)雜志的贊許。一年后的夏天,樂團獲邀于英國切爾滕納姆(Cheltenham)與利奇菲爾德(Lichfield )音樂節亮相。然后是2015年,樂團搬演了馬勒《第八交響曲》——聲名遠播的“千人交響曲”(雖然舞臺上大約只有350人)。兩年后,樂團搬演了英格伯特·洪佩爾丁克(Englebert Humperdinck)的《漢澤爾與格蕾泰爾》(Hansel and Gretel

)半舞臺版制作。到了2018年,搬演了倫納德·伯恩斯坦(Leonard Bernstein)的《彌撒》(Mass

)。這種無所畏懼的精神贏得當地媒體激賞,與樂季編排平平無奇的新加坡交響樂團(尤其是領導該團多年的音樂總監水藍去年卸任后相比),形成很大的反差。我們回顧一下此次創樂者樂團制作的瓦格納龐大樂隊編制的《女武神》以及近30萬歐元的制作費用吧。這個制作不算“徹底”的本土化——只有兩位演員(飾演九名女武神中的成員)來自新加坡,其他演員從美國、英國與澳大利亞遠道而來——但導演與制作團隊都來自新加坡,皆為當地戲劇界的中堅人物。

在導演伊蒂絲·普德斯塔(Edith Podesta)的構思里,樂團坐在舞臺中央,穿上戲服的演員則位于樂團前下方(升高了的樂池區)以及樂團后上方(舞臺后建造了代表瓦爾哈拉的山峰,演員得經常上上下下)。大型的投影除提供英語字幕之外,更展示出一些由瓦格納的主導動機(leitmotif)所衍生出的視覺設計,也有現場演出的即時視像特寫(讓大家看得清演員的面部表情)。于是,多層次的細膩感情與瓦格納龐大的音樂編制相得益彰,特別是當演員們分隔在舞臺兩邊的時候。

所有這些設計讓我們意識到這個制作實際上是圍繞著樂團展開的。創樂者交響樂團在陳子樂——他是樂團創辦人之一,同時擔任音樂總監——指揮下,這群非職業樂手大致上成功地應對了這次挑戰。弦樂像是一堵精亮的音墻,聽起來統一、準確、遼闊。個別木管與銅管樂手也許不習慣從樂隊中突顯出來——也可能是耐力不夠——所以偶爾的出現了錯失。最重要的是,陳子樂對于瓦格納風格把握得很好,樂手們堅定而頑強地奏完等同于兩套交響樂音樂會時長的曲目。總的來說,這場演出與眾多歐洲歌劇院的水平不相上下。

***

下一站是曼谷。在那里,我遇上一群學生。2001年,曼谷歌劇院(Bangkok Opera)(后來改名暹羅歌劇院,Opera Siam)由桑姆托·蘇恰里故(Somtow Sucharitkul)創辦。這位泰國出生但在英國接受過教育的作家與作曲家,創辦歌劇院的初衷,跟新加坡創樂者交響樂團開頭一樣,都是小型院團。可是歌劇院的藝術宗旨隨著創辦人善變的思維而有所變動。暹羅歌劇院也是東南亞首家開拓《指環》制作的表演團體,雖然至今已兩度推遲《齊格弗里德》的制作。在過去幾年里,歌劇院制作了自己出品的史詩式歌劇:桑姆托撰寫的《佛陀本生十世》(Ten Lives of the Buddha

),至今已經演了六部。

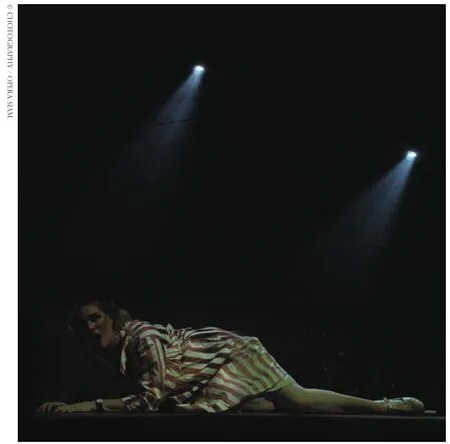

新加坡創樂者交響樂團制作的《女武神》劇照(攝影:許智勇)

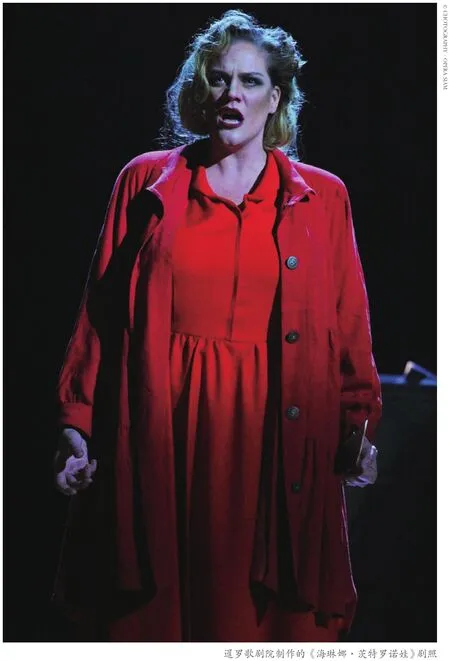

今年1月中旬,桑姆托的最新歌劇作品《海琳娜·茨特羅諾娃》(Helena Citrónová

)搶先公演,歌劇《佛陀》的第七部也因而被推遲。從各個層次來看,《海琳娜》代表了嶄新的出發點。劇本根據真人真事改編,描述了被困在奧斯威辛集中營的猶太女子與一名納粹侍衛墜入愛河的故事,劇情發展所利用的音樂混合了無調性旋律及當時的流行音樂曲風,樂團襯托的音樂令人聯想起伯納德·赫爾曼(Bernard Herrmann)的管弦樂配器;臺上更設有猶太克萊茲默(klezmer)小樂隊,在適當的時候加入演奏,讓我們在跟隨故事的發展的同時,時不時還能耳目一新。就像創樂者交響樂團的模式,暹羅歌劇院只聘用了幾位本地歌唱家擔任配角,其他主演來自世界各地。整場演出的情感迂回路轉,故事的兩位主角——美國女高音卡桑德拉·布萊克(Cassandra Black)飾演海琳娜、德國男中音法爾克·赫尼茨(Falko H?nisch)飾演納粹侍衛法蘭茨·弗恩舒(Franz Wunsch)——合演多段二重唱,有時候富有戲劇張力,有時候抒情至極。這部歌劇的原動力來自樂池中的管弦樂團。指揮特里斯蒂·納·帕塔楞(Trisdee na Patalung)融匯了總譜中包含的多種風格,把它們糅合成為一體,負責演奏的暹羅小交響樂團(Siam Sinfonietta)在帕塔楞的引領下,充滿激情,信心堅定。演出結束后,我才知道暹羅小交響樂團的團員年齡從12歲到25歲不等,樂團中有幾位年輕的職業樂手,由他們帶領著曼谷各中學的學生樂手一起演奏。

上、左頁:暹羅歌劇院制作的《海琳娜·茨特羅諾娃》 劇照

不知何故,我聽聞這個消息后,并不感到驚訝。新加坡創樂者交響樂團對所謂“業余”(amateur)的界定,其實是根據這個英文詞匯的拉丁詞根:他們愛好音樂,所以彈奏音樂。很多不依靠音樂賺錢的音樂家寧愿用“非職業”(avocational)這個詞語,因為“業余”隱喻著馬虎與非內行的貶義。在我印象中最難忘的演出,有不少是名副其實“愛好者”的演出,而不是那些按時鐘計算薪水的音樂家。反過來,我經歷過不少“職業樂手”無精打采的音樂會:他們排練充分,演奏出來的表面音色十全十美,可是內心的激情火花完全熄滅了。有一次,在聽過一場死氣沉沉的音樂會后,我描述那場演出是“音樂停尸間”:那里的音樂已經“死去”了,可它比還“活著”的時候更悅耳。

創樂者交響樂團可以為觀眾獻上專業水準的演出,是因為1.從他們的角度來看,判斷演出的成功與否的根據,是演奏的效果,而不是薪酬多少;2.每年只演幾場音樂會,可以為每一場音樂會的曲目投入更多的時間。同樣地,暹羅小交響樂團的學生們可能永遠都達不到職業樂團那種打磨得非常光滑的音效,但年輕人帶來的,是剛剛發現音樂美妙之處時那毫無保留的興奮和純粹。我可以保證,很多膩煩的職業音樂家一看到桑姆托的樂譜就會貶低這部歌劇,因為首先它是新作品,其次它不是瓦格納作品。

完全漠視職業音樂家當然也不公平。科班出身的職業音樂家不但能展示卓越的演奏技藝,而且無論演出多少場次還能確保同樣的高水平。創樂者交響樂團此番只安排了一場《女武神》演出,倘若他們加演第二場——或者暹羅歌劇院連續三晚搬演《海琳娜·茨特羅諾娃》——樂團團員由腎上腺素激發的動力,能與首場演出時保持一致嗎?大概不行。因為我觀看的都是首演場次,所以我真的不在乎。

上、左頁:暹羅歌劇院制作的《海琳娜·茨特羅諾娃》 劇照

A couple of months ago I wrote that there were two types of orchestras: symphonic ensembles and pit bands.It made sense at the time, but since then I’ve found a couple of loopholes.

I don’t mean a loophole like Jeremy Geffen, the former Carnegie Hall director of artistic planning,telling me he follows all the Jewish dietary rules“except for bacon.” That’s more of a paradigm shift.This is a simple case of choosing different generalizations and ambiguities to emphasize.

Virgil Thomson, who started the whole “two types of orchestras” thing, loved sweeping generalizations, mostly because they annoy all the right people.But he didn’t do it recklessly: His own two orchestral categories—“the monumental and the directly functional”—included amateur and student groups as the bottom rung of the second.

Having been around amateur and student musicians my whole conscious life, I knew just how well they would respond to that—i.e., not favorably—so I avoided the subject altogether.After last month, though, I’m back to amateurs and students.In fact, I’m arguing for their promotion.

***

In early January, I was in Singapore for the local premiere ofDie Walküre

—not just a rare Wagner production in the region but actually the launch of what might well end up as the first completed Ring Cycle in Southeast Asia.And let the record state, this was not produced by the Singapore Lyric Opera, or even the Singapore Symphony Orchestra, but rather a group of amateur musicians called the Orchestra of Music Makers.Let’s look at this again: the most challenging corner in the Western operatic canon appeared in Singapore through the efforts of a group of doctors,attorneys and businessmen.OMM first began playing together in 2008 when a group of secondary school music students essentially agreed to their parents’ demands to “get real jobs,” but still refused to give up music.

At first, they weren’t even sure they wanted to play in public, but those doubts ended quickly.Business and law degrees usually instill a certain amount of self-assurance, as well as a few administrative skills,and soon OMM (with a grown-up conductor and a professional concertmaster) was playing regularly at the Esplanade, Singapore’s preeminent performing arts center.The orchestra’s 2011 recording of Mahler’s “Resurrection” Symphony, featured on Singapore Airlines’ in-flight playlist and favourably reviewed in England’sGramophone

magazine,resulted in invitations to the Cheltenham and Lichfield music festivals the following year.Then there was their 2015 performance of Mahler’s Eighth—the famous “Symphony of a Thousand” (albeit with only about 350 on stage)—then two years later, a semi-staged production of Humperdinck’s operaHansel and Gretel

, then a 2018 staging of Leonard Bernstein’sMass

.Such fearlessness has been heavily lauded in the local press, in contrast with the lack of interesting programming coming from the Singapore Symphony Orchestra ever since their longtime music director Lan Shui stepped down a year ago.But back toWalküre

, with its full Wagnerian orchestra and nearly €300,000 production budget.This was not anentirely

local effort—only two cast members, both playing Valkyries, were from Singapore, the rest of the singers coming from the US, UK and Australia—but the director and production team were all recruited from Singapore’s active theatre community.Director Edith Podesta’s conception kept the orchestra center stage, while a fully costumed cast moved both in front and below (occupying what would usually be the orchestra pit) and behind and above (scaling a makeshift mountain to represent Valhalla at the rear of the stage).Large-scale projections offered not only English translations but also recurring visualisations of Wagner’s leitmotifs and frequent close-ups of the singers, bringing layers of emotional intimacy to the score’s epic scope, particularly when the singers themselves were placed on opposite sides of the stage.

All of this meant that the story literally revolved around the orchestra, and with OMM music director and co-founder Chan Tze Law on the podium the amateurs mostly rose to the occasion.String playing was a polished sonic wall, uniformly precise and expansive, a few occasional cracks coming from individual wind and brass players not used to the exposure—or, perhaps the endurance—required.Above all, Chan commanded a sure sense of idiom, the musicians powering through the equivalent of two backto-back symphonic programs.And ultimately, the evening was indistinguishable from many provincial European opera houses.

***

Siegfried

twice.In the meantime, they’ve launched their own homegrown epic, namely Somtow’sTen Lives of the Buddha

, which is currently up to episode six.

新加坡創樂者交響樂團制作的《女武神》劇照(攝影:許智勇)

Buddha, too, got pre-empted in mid-January by Somtow’s latest opera,Helena Citrónová

, which was a departure on every level.The libretto,inspired by a true story of a Jewish prisoner in Auschwitz and her relationship with a Nazi guard,unfolded in an eclectic mix of atonal musical themes and epochal popular tunes, all held together by a Bernard Herrmann-like orchestral backdrop with an onstage klezmer band to cleanse the aural palate as needed.Like OMM’sWalküre

,Opera Siam’s Helena had a handful of local singers in secondary roles amidst a largely international cast.Emotionally, the evening took its cues directly from the American soprano Cassandra Black (as Helena) and German baritone Falko H?nisch (as the Nazi guard), in a series of duets that ranged from dramatic to lyrical.The musical momentum, though, came from the orchestra pit, where conductor Trisdee na Patalung fused the score’s diverse musical influences into a seamless whole, coaxing passionate commitment from the Siam Sinfonietta.Only later did I find out that the players ranged in age from 12 to 25, a few young professional musicians helming students from Bangkok’s secondary schools.

Somehow, though, I was not surprised.OMM was“amateur” only in the original Latin roots of the word,doing things for the love of it.Many non-professionals call themselves “avocational” to avoid the taint of their sloppier, inexpert colleagues.And yet, some of the most memorable performances I’ve attended have hailed from trueamateurs

rather mercenaries playing music with one eye on the clock.Conversely,some of the most lifeless performances I’ve ever encountered have been by “professionals,” rehearsed to the point of surface perfection with the inner spark completely extinguished.I once compared a particular lifeless performance to a musical mortuary where the music was dead but sounded better than it did when it was alive.The OMM can deliver a professional quality product specifically because (a) they’re more invested in the musical results than the paycheck,and (b) they play fewer concerts and can devote more time to each one.Likewise, student groups like the Siam Sinfonietta will never achieve a professional’s sonic polish, but they bring to the table the sheer excitement of discovering something for the first time.I could list plenty of jaded professionals who would’ve discounted Somtow’s score simply because (a) it was new, and (b) it wasn’t Wagner.

Let’s not disregard the professionals entirely.The true mark of grown-up playing is not simply high quality, but rather delivering it consistently night after night.OMM presented only one performance.Would a secondWalküre

—or the third night of Opera Siam’sHelena Citrónová

—be as adrenaline-fueled as the first? Probably not.But since I was there for both on opening night, I really don’t care.