Taking central nervous system regenerative therapies to the clinic: curing rodents versus nonhuman primates versus humans

Magdalini Tsintou , Kyriakos Dalamagkas , Nikos Makris

1 Departments of Psychiatry and Neurology Services, Center for Neural Systems Investigations, Center for Morphometric Analysis, Athinoula A.Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA 2 Department of Psychiatry, Psychiatry Neuroimaging Laboratory, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA 3 University College of London Division of Surgery & Interventional Science, Center for Nanotechnology & Regenerative Medicine, University College London, London, UK 4 Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX, USA 5 The Institute for Rehabilitation and Research Memorial Hermann Research Center, The Institute for Rehabilitation and Research Memorial Hermann Hospital, Houston, TX, USA 6 Department of Anatomy & Neurobiology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA, USA

Abstract The central nervous system is known to have limited regenerative capacity. Not only does this halt the human body's reparative processes after central nervous system lesions, but it also impedes the establishment of effective and safe therapeutic options for such patients. Despite the high prevalence of stroke and spinal cord injury in the general population, these conditions remain incurable and place a heavy burden on patients' families and on society more broadly. Neuroregeneration and neural engineering are diverse biomedical fields that attempt reparative treatments, utilizing stem cells-based strategies, biologically active molecules, nanotechnology, exosomes and highly tunable biodegradable systems (e.g., certain hydrogels).Although there are studies demonstrating promising preclinical results, safe clinical translation has not yet been accomplished. A key gap in clinical translation is the absence of an ideal animal or ex vivo model that can perfectly simulate the human microenvironment, and also correspond to all the complex pathophysiological and neuroanatomical factors that affect functional outcomes in humans after central nervous system injury. Such an ideal model does not currently exist, but it seems that the nonhuman primate model is uniquely qualified for this role, given its close resemblance to humans. This review considers some regenerative therapies for central nervous system repair that hold promise for future clinical translation. In addition, it attempts to uncover some of the main reasons why clinical translation might fail without the implementation of nonhuman primate models in the research pipeline.

Key Words: animal models; central nervous system regeneration; clinical translation; exosomes; hydrogels;neural tissue engineering; nonhuman primates; spinal cord injury; stem cells; stroke

Introduction

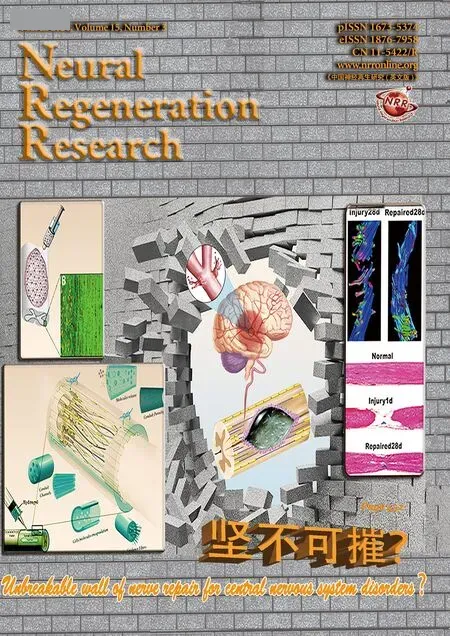

The central nervous system (CNS) is known to have a limited regenerative capacity (Boni et al., 2018; Hussain et al.,2018; Gorabi et al., 2019), making the path toward the development of effective therapeutic strategies challenging. Stroke and spinal cord injury (SCI) are highly prevalent neurological entities with tremendous impact on society. Yet, despite numerous research attempts to uncover solutions to the CNS regeneration problem, these conditions remain incurable.Neurite regrowth after brain injury is limited due to a diminished intrinsic capacity of the neurons to grow and an inhibitory extrinsic environment (Cheah and Andrews, 2016;Yu and Gu, 2019). This “unbreakable wall” toward solutions for incurable CNS conditions is currently being targeted by novel regenerative therapies with the utilization of advanced neuroimaging modalities to quantify restorative effects and establish reproducible and clinically applicable treatments(Figure 1).

Neuroregeneration and neural tissue engineering are highly diverse, relatively new biomedical fields that have the potential to target the cause of CNS conditions, and not only symptoms like currently used conventional clinical treatments. As such, they offer promising future treatment options. The main problem impeding the effective clinical translation of such therapies is the gap that exists in the translational pipeline due to interspecies pathophysiological and neuroanatomical differences (Tsintou et al., 2016).Experimental studies in animals such as mice have demonstrated curative techniques for severe and intractable CNS disorders such as stroke and SCI. However, we fail to cure humans when the therapies reach randomized clinical trials,suggesting that something is problematic with the translation pipeline.

The first part of this review discusses some promising regenerative interventions (i.e., stem cells, exosomes and hydrogels use) for stroke and SCI, based on the most recent literature and the treatments that have managed to reach clinical trials. The second part analyzes some key interspecies differences that may affect functional outcomes, potentially leading to failure at the level of clinical trials. This review focuses solely on stroke and SCI, considering those key conditions the starting point for establishing therapeutic strategies for other CNS conditions. The aim is to point out treatments that hold promise for the cure of presently incurable CNS conditions, consider factors that may impede clinical translation of those therapies, and suggest potential strategies to improve the translatability of potential treatments.

To this end, we conducted an electronic search on PubMed and Google Scholar using search terms such as ‘stroke AND stem cells', ‘stroke AND nerve repair', ‘spinal cord injury AND stem cells', ‘spinal cord injury AND nerve repair', ‘central nervous system AND repair AND translation', ‘human AND nonhuman primate AND CNS AND translation', ‘human AND rodent AND CNS AND translation, and ‘species AND divergence AND motor'. Articles were reviewed for each search after being sorted by ‘best match'. Subsequently, the results of the same search were sorted by ‘most recent'. The results were further screened by title and abstract to ensure relevance to the reviewed topics. Up to 100 articles were reviewed for each search outcome with no filtering based on publication dates to avoid missing important historic neuroanatomical data. This is why some older publications are cited in this review. Certain significant citations within the papers examined were also reviewed after independent searches.

Selected Promising Central Nervous System Regenerative Therapies with Potential for Clinical Translation

The pathophysiological basis of the inability to fully restore function after a CNS injury in humans is a matter of ineffective neuroregeneration. Thus, it is logical to target the neuroregeneration problem as a means of finding an effective curative, rather than symptomatic, therapy. Cellular,acellular or combinatorial approaches utilizing principles from the highly diverse fields of neural tissue engineering and nanotechnology have been attempted with highly promising results and occasionally impressive outcomes, mostly in rodent preclinical models (Lu et al., 2012). Figure 2 illustrates the stem cells that have moved forward to clinical trials for the treatment of stroke, but it also portrays a model of evolution for translational treatments, demonstrating the tendency to shift toward cell enhancement methodologies(e.g., biomaterials/scaffolds, cytokines, micrornas), as well as acellular techniques using, e.g., exosomes, growth factors,and non-coding RNAs. In the following section we will focus only on regenerative therapies that have managed to reach the stage of clinical trials. For the purposes of this review, we will mention only studies targeting adults that are currently registered in ClinicalTrials.gov, excluding withdrawn, suspended or terminated studies.

Stem cell-based therapies and their mechanism of reparative action

In recent years, stem cell-based therapies have revolutionized medicine. Naturally, apart from the several other applications tested, stem cells have been used for CNS applications with impressive results in preclinical animal models. Thus,certain stem cells, either alone or combined with hydrogels or other scaffolds, have been used to induce neuroregeneration, and some have even reached the stage of clinical trials.Tables 1 and 2 summarize stem cell-based therapeutic interventions currently shown as ongoing in the ClinicalTrials.gov website for stroke and SCI, respectively.

Although there are several cell types that some may argue could be the future of regenerative neurology, such as the induced pluripotent stem cells, in fact only a few types of stem cells have reached clinical trials. Future studies may allow for techniques to mature and more data to accumulate, so that more cell types can be added to that list. Currently, based on the registered clinical trials, the major stem cell lines most often used for preclinical applications, potentially moving one step closer to clinical practice, are mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), hematopoietic stem cells and bone marrow mononuclear cells.

The therapeutic potential of bone marrow MSC for stroke is by far the most widely studied in preclinical and clinical research. Bone marrow MSCs seem to be an attractive candidate for stem cell neural repair therapies because of the lack of ethical concerns associated with their use, in contrast to the use of fetal cells. Although further studies are needed to gain a better understanding of the potential mechanisms involved, some effects of bone marrow MSC transplantation in preclinical models include sensorimotor function enhancement (Huang et al., 2013), synaptogenesis promotion,nerve regeneration stimulation (Abbas et al., 2019), tissue plasminogen activator-induced brain damage reduction (Liu et al., 2012b) and immunomodulation (Weiss and Dahlke,2019). However, the bone marrow MSCs' ability to replace dead or damaged neuronal and glial elements requires further verification.

By contrast, despite the limited implementation in clinical trials to date - possibly due to prior concerns regarding the ethically controversial use of fetal or embryonic cellular tissues (Ramos-Zú?iga et al., 2012), as well as the immunogenicity of the allogenic graft (Aboody et al., 2011) - another hot research area for neurobiologists regards transplantation of neural stem cells (NSCs) given their ability to differentiate into different neuronal and glial elements that form the CNS. In mammalian brains, NSCs have been shown to migrate naturally to areas of injury and neurodegeneration.Embryonic NSCs have been found to migrate to the ischemic lesion after ischemic stroke in rat models. Subsequently, they have been shown to mature into neurons (Darsalia et al., 2007; Takahashi et al., 2008), astrocytes and microglia(Guzman et al., 2008), restoring impaired sensorimotor and spatial learning functions (Mine et al., 2013). Even in a nonhuman primate stroke model, NSCs partially differentiated into neurons after engraftment and survived up to 105 days(Roitberg et al., 2006), showing promise for future clinical trials. It is anticipated that the use of NSCs might increase in future clinical trials given the advent of cellular reprogramming techniques (Liu et al., 2012a; McCaughey-Chapman and Connor, 2018) or even the direct lineage conversion of somatic cells into induced neural cells in vitro (Vierbuchen et al., 2010; Lujan et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2013). Such advancements avoid the prior ethical controversy and increase the clinical potential of NSCs.

The mechanisms of action of NSCs after transplantation to the injured host can be divided into endogenous (host-dependent) and exogenous (transplanted stem-cells-dependent). Figure 3 depicts both endogenous and exogenous mechanisms. In particular, some of the endogenous mechanisms of NSCs' actions are: 1) host-dependent induction of proliferation and differentiation of NSCs via trophic factors;2) host-induced chemoattraction of the transplanted stem

cells to the site of injury; 3) NSCs' behavior and survival pattern modification through locally released immune cell-derived factors; and 4) host-initiated graft-rejection-like processes. By contrast, as noted in Figure 3, exogenous mechanisms involve the NSCs per se, with actions such as:1) in situ NSC differentiation toward the neuronal and glial lineage for cell replacement in the injury site and subsequent functional integration within the host's pre-existing neuronal circuits; 2) NSC-derived neurotrophic and neurogenic factors' release triggering the endogenous neuroregenerative and neuroprotective mechanisms of the host; and 3) stem cells' influence on the host, leading to bilateral modulation of the transplanted cells and the host's immune system (Oliveira et al., 2016). Among all of these mechanisms, a major mechanism by which NSCs lead to post-stroke neural functional improvement is the release of soluble trophic factors and cytokines (Smith et al., 2012).

Table 1 Summary of stem cell-based therapeutic interventions regarding stroke in ClinicalTrials.gov

Table 2 Summary of stem cell-based therapeutic interventions regarding SCI in ClinicalTrials.gov

Thus, stem cell transplantation has been demonstrated to trigger neural recovery through several mechanisms. Some of the described mechanisms include cell replacement, trophic influences, immunomodulation, and enhancement of endogenous repair processes. Nevertheless, despite advances in the field and the potential of stem cell use for neuroregenerative purposes, as pointed out in Figure 2, the future takes translational research toward cell-free concepts, with the use of exosomes as one of the most promising for future clinical applications due to several benefits it may entail.

Exosome-based therapies and their mechanism of reparative action

Exosomes are endosome-derived small extracellular vesicles released from cells to the extracellular space after an intermediate endocytic compartment, the multivesicular body, is fused with the plasma membrane to ultimately form exosomes (Edgar, 2016). Just like the most prominent extracellular vesicles that respond to intercellular communication and cellular immunity, exosomes are nano-sized (30-100 nm) and contain several types of nucleic acids and proteins(Jo et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2015).

Although it was initially believed that transplanted stem cells would differentiate into the target tissue, thereby inducing their effects, there is an increasing amount of research showing that transplanted stem cells are more likely to exert their function in a paracrine manner, by secreting extracellular vesicles, i.e., exosomes (Ratajczak et al., 2012; Shen et al.,2013; Liang et al., 2014; Song et al., 2014). Stem cell-derived exosomes have been found to promote tissue repair and regeneration, while it is believed that exosome inclusions induce epigenetic changes in the recipient's cells, positively regulating their fates by promoting proliferation or inhibiting apoptosis (Zhou et al., 2013; Tan et al., 2014; Nakamura et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2015a, 2016; Nong et al., 2016; Qi et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2018).

Further research is needed to determine the exact mechanisms by which exosomes can promote neuroregeneration.Nevertheless, emerging data indicate that treatment of stroke and traumatic brain injury with MSC-derived exosomes facilitates interwoven brain repair processes, including neurite remodeling, thereby improving neurological function (Xin et al., 2013a, b; Zhang et al., 2015b). Stimulation of axonal growth of cortical neurons, as well as angiogenesis have also been associated with exosomes (Zhang et al., 2017b). Finally,MSC-derived exosomes have been found to enhance functional recovery in rodent stroke models, promoting axonal plasticity and neurite remodeling in the perilesional cortex through the microRNA 133b (Xin et al., 2013b). In agreement with this finding, microRNA 124 (miR-124)-loaded exosomes have been found to ameliorate brain injury by promoting neurogenesis (Yang et al., 2017).

Thus, exosomes seem to be a promising acellular therapeutic strategy for inducing neural repair after CNS injury,providing several benefits over the use of cells. Unlike cells,acute immune rejection is not elicited by exosomes since they are nonviable and much smaller. In addition, the use of exosomes as “natural” delivery vehicles, i.e., for the safe,stable, targeted and concentrated delivery of agents such as curcumin, can be the basis of novel nanoparticle drug delivery systems to induce desired effects (Sun et al., 2010).Carcinogenesis and embolism have been a point of concern for cells, but this does not apply to exosomes, which have reduced safety risks linked to their use. Technically speaking,cell-based therapies rely on high-maintenance protocols,which can be costly given the need to maintain viability. This does not apply to exosomes, thereby minimizing complexity and expenses. The unique characteristics of exosomes can increase clinical translatability of certain novel therapies in the future. Figure 4 illustrates some advantages of using MSC-derived exosomes/microvesicles in conjunction with 3-dimensional MSC-cultures for efficient scalable production, pointing to the potential of using such acellular methods for neural repair.

There is already one clinical trial (NCT03384433) Phase I/II registered in ClinicalTrials.gov, which should have begun recently, in October 2018. This trial attempts to test the functional outcomes and possible adverse effects after delivery of 200 mcg total protein of allogenic MSC-generated exosome transfected by miR-124, one month after cerebral infarction via stereotaxis. Nevertheless, the therapeutics based on MSC-derived exosomes still face challenges due to their short half-life and rapid clearance by the innate immune system in vivo (Imai et al., 2015). Damaged neural tissue requires time to heal through a complex multiphase process.However, based on prior studies, retaining the unconjugated exosomes in the lesion site for an extended period of time is not realistic (Imai et al., 2015). The use of nanotechnology,as discussed below, could offer pioneering options to tackle these obstacles. Hydrogel matrices could impede the rapid clearance and accomplish targeted, sustained release of exosomes, tuned based on the period of time needed to attain a beneficial functional outcome with CNS tissue repair.

Hydrogel-based or combinatorial therapies and the rationale behind such methods

The mechanical gap after a CNS lesion occurs combined with the highly hostile microenvironment of the CNS for neuroregeneration has led scientists to utilize not only bioactive substances to induce neuroregeneration, but also mechanical bridges or scaffolds to facilitate the healing process.In rodents and other small animal models, the size of the lesion is not sufficient to impede the regenerative processes and affect the therapeutic interventions tested. In humans,however, the size is much larger, causing the same successful therapeutic strategies used in rodents to fail. The key issue is that even if stem cells were transplanted in humans to induce neuroregeneration, and axonal growth was accomplished,the effects of the treatment would wear off before the growth was adequate to bridge the gap in the damaged tissue. Nerve fibers would elongate with no guidance, in random directions, making the task of effectively bridging the gap impossible. This is why it is important to use some sort of biocompatible and biodegradable scaffold to create a temporary bridge that provides mechanical cues for nerve growth to occur. Another important factor that scientists have considered before moving toward more combinatorial approaches that involve the use of hydrogels or other scaffolds, is that the substances tested cannot be effectively retained in the lesion site to minimize unwanted generalized effects while also maximizing desired targeted effects. As a result, therapeutic agents are often rapidly cleared or become unstable in the CNS microenvironment without proper structural support and protection (Liu et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2018).

There are many kinds of scaffolds that have been designed for neural tissue engineering purposes, but the most appropriate and effective for CNS use are hydrogels (Wang et al., 2018). The classification category of a hydrogel (e.g.,its porosity, physical structure, source, ionic charge, and crosslinks) can already provide important information on whether a hydrogel is appropriate for a specific tissue repair attempt or the delivery of a bioactive substance, such as a drug, growth factors, cells, and other substances or molecules, to the cells or tissues where the hydrogel is applied to promote a certain effect. Therefore, not all hydrogels are helpful for facilitating neural repair. Based on prior experimental work in the field by the authors of this paper (Tsintou et al., 2018) and several other scientific teams (Assun??o-Silva et al., 2015; Tuladhar et al., 2018), an ideal hydrogel for CNS regeneration requires the following: 1) in situ gelling at the CNS lesion site to achieve an accurate fit with irregularly shaped tissue defects; 2) effective retention and stabilization of any bioactive molecules, cells or exosomes used, to avoid rapid clearance and reactions caused by non-targeted treatment applications; 3) hydrogel-CNS tissue integration in a way that significantly facilitates the migration of circumjacent cells into the hydrogel scaffold, mimicking the CNS microenvironment, ideally with mechanical cues to guide axonal growth in the correct direction for the establishment of functional synapses; 4) biodegradability of the hydrogel to allow for the scaffold to gradually disintegrate, maintaining the structural and nourishing support for at least the amount of time needed for effective regeneration to occur, while also avoiding a potential second surgery to remove the scaffold;and 5) tuneability of the hydrogel system not only to allow for the aforementioned requirements to be fulfilled, but also to permit development of sustained release systems to pace the release of the desired therapeutic substance to achieve maximum effect.

At the present time, to the best of our knowledge, only NeuroRegen and NWL's Regeneration MatrixTM(RMxTM)scaffolds for SCI in combination with stem cells have managed to reach the stage of clinical trials (phases I/II) registered in the ClinicalTrials.gov website (studies NCT02688049 and NCT02352077 for NeuroRegen and NCT02326662 for RMxTM). NeuroRegen is a linearly ordered collagen scaffold that has demonstrated promising preclinical results in rodents and dogs with SCI, moving towards clinical trials in order to establish the safety and efficiency of the proposed treatment. Collagen is a type of extracellular matrix with excellent biocompatibility and biodegradability, enabling the use of collagen-based scaffolds for CNS applications with good results. The researchers involved in those clinical trials recently published some results indicating potential safety and efficiency of the scaffold in terms of promoting functional recovery (Xiao et al.,2016, 2018; Zhao et al., 2017), in agreement with their preclinical reports (Li et al., 2017). However, these data are not sufficient for accurately estimating whether the proposed treatment might work in future clinical applications. Nevertheless, this is the first step toward a promising future in clinical trials of combinatorial regenerative approaches. The RMx? biomatrix is a novel self-assembling 3-dimensional biomaterial with intricate physical characteristics that aim to mimic the matrix in regenerating tissues (https://www.fortunafix.com/technologies).

Another highly promising hydrogel-based therapeutic strategy not yet ready to be implemented in the clinic, but with demonstrated potential, is the use of miniature hydrogel micro-columns for the transplantation of micro-tissue engineered neural networks (Harris et al., 2016). This minimally invasive technique is able to facilitate neural repair by simultaneously providing neuronal replacement and physical reconstruction of long-distance axonal pathways in the brain. In an attempt to optimize the model, the research team has developed a computational growth model for micro-tissue engineered neural networks (https://github.com/PSUCompBio/GrowthModel) (Marinov et al., 2018), taking advantage of current technological advances that could accelerate clinical applications.

Animal Models in the Pathway toward Clinical Translation

Preclinical animal models have been widely used over the years in order to establish the safety and efficiency of a potential treatment before moving toward clinical trials in humans. Figure 5A depicts the current reality in the research community for the discovery of therapies. Figure 5B, by contrast, shows our proposed ideal model of “rodent-monkey-human”, which would increase the translatability of regenerative therapies and could allow for reductions not only in financial cost, but also the cost in human lives. It should be noted that most current research is being done in rodents,which demonstrate significant differences compared to humans. Given the occasionally impressive results in rodent models of regenerative therapies, there have been attempts to translate potential therapies directly from rodents to humans with no intermediate step. Such attempts mainly involved companies attempting to accelerate the path toward clinical translation of their potential therapies. However, not surprisingly given interspecies differences, these clinical trials ultimately failed. The next section summarizes some key interspecies differences and stresses the importance of using nonhuman primate models to attempt to minimize risk and attain more beneficial clinical outcomes.

There are important, long-standing ethical questions regarding the use of any animal species for research (Tsintou et al., 2016). Regulations such as the American Welfare Act(AWA) in United States are present in order to ensure the well-being of animals used in research settings, but those regulations are far from ideal. 90-95% of the animals used in research laboratories are currently excluded from AWA,while for the 10% of larger animals covered by AWA (dogs,cats, non-human primates, guinea pigs, hamsters, rabbits and other warm-blooded animals) the minimal standards for housing, feeding, handling, veterinary care or psychological care, where applicable, are strictly regulated. This makes it more difficult for the regulated animals to be used for research purposes unless there is proper justification. The shifttowards animal species not covered by AWA for research purposes bears an additional risk of increasing unjustified rodent use for translational purposes. Thus, developing new regulatory requirements to ensure the appropriate, justified use of certain animals for research purposes, with proper husbandry techniques, is a necessity. Moreover, research exploring the distress mechanisms of animals during therapeutic interventions could potentially shed light on what might be missing from protocols aimed at minimizing animals' stress and suffering during research procedures. The stricter regulations regarding larger research animals (i.e.,nonhuman primates or companion domesticated animals)could stem from the notable ethical concerns linked to their closer relationship and integration with human society. It is important for preliminary testing to occur in smaller animals in an attempt to understand mechanisms and potential limitations before attempting the use of larger animals, thus moving in a stepwise manner toward a safe clinical translation pipeline.

Given the discrepancies in functional outcomes even when clinical translation is attempted using the best preclinical models currently available, our proposed “ideal model”with nonhuman primates serving as a bridge from rodents to humans seems timely. For the time being, the use of larger animals, especially nonhuman primate models, remains a necessity for fully understanding and treating disorders of the human CNS that involve complicated neuronal networks that underpin life-threatening or highly debilitating conditions with tremendous societal impact. Proposed technological alternatives to obviate the use of nonhuman primates presently include: 1) ex vivo “artificial humans” with engineered organs resembling the function, hierarchy and complexity of the actual human body; 2) virtual systems and holograms that can simulate the full complexity of the human CNS and mimic the detrimental effects of a CNS injury,while also mimicking the pathophysiological mechanisms and effects of a potential regenerative therapy in a computerized system; and 3) organs-on-a-chip for ex vivo trials of potential regenerative therapies prior to human use, such as the recently developed Brain-Chip of the start-up company Emulate that is a preliminary, early-stage attempt to mimic brain physiology and the blood-brain barrier. Therefore,animal models, and especially nonhuman primate models,remain crucial for the safe and effective clinical translation of therapies.

Rodent models versus nonhuman primate models versus humans

Rodents, nonhuman primates and humans demonstrate crucial differences in qualities such as size, neuroanatomy,behavior, and pathophysiology. This raises the question of how these differences impact the restorative effect of a tested treatment, the functional impact on the subject after an intervention, the maintenance of desired results, and the emergence of adverse effects as well as their severity. The section below will attempt to shed some light on key interspecies differences that might affect the clinical translation of regenerative therapies after CNS injury.Size

This is perhaps the most obvious difference between the commonly used, readily available rodent models and nonhuman primates or humans. The rodent nervous system not only is much less complex with fewer synapses within neuronal networks, but it is also significantly smaller than those of nonhuman primates or humans. To illustrate the scale difference, the size of the mouse brain is 1/1000ththat of the human. Encephalization is a measure of brain size relative to a taxonomic standard. Nonhuman primate brains closely resemble human brains on a variety of criteria, including encephalization, number and density of cortical neurons, and greater myelination compared to other, lower order mammals (Ventura-Antunes et al., 2013; Phillips et al., 2014). For example, the encephalization quotient for humans is 7.4-7.8,for Old World monkeys 1.7-2.7, and for capuchin monkeys 2.4-4.8; by contrast, rodents are in the 0.4-0.5 range (Phillips et al., 2014). Figure 6 depicts the brain mass and total number of neurons for the mammalian species examined to date with the isotropic fractionator to better exemplify significant interspecies differences.

Thus, an intervention that results in axonal sprouting of a few millimeters might be highly effective for the mouse,resulting in functional recovery, but the same intervention would hardly make a difference in humans, who normally need to overcome lesions of over a few centimeters instead(Tsintou et al., 2016). No matter how impressive the results are after an intervention is tested in rodents, patience and caution are warranted in moving toward clinical translation.Given the major differences between rodents and primates,it is not surprising that several Phase II and III clinical trials have failed when the study relied only on preclinical rodent data to accelerate the translation pipeline (Llovera and Liesz, 2016).

Neuroanatomical differences

Even though there is remarkable conservation among the motor systems of vertebrates, there are pronounced quantitative and qualitative differences between rodents and primates in terms of the number, location and termination patterns of significant fiber tracts, such as the corticospinal tract (CST), due to certain evolutionary changes (Friedli et al., 2015; Filipp et al., 2019).

The motor cortex, which is of particular clinical significance for functional recovery after stroke or SCI, projects extensively to brainstem and spinal motor neurons in primates, contrary to its connections in lower order mammals(Lawrence and Kuypers, 1968; Galea and Darian-Smith,1997; Lacroix et al., 2004). This allows the CST of primates to influence motor neurons both directly and indirectly (Lemon et al., 2004; Riddle et al., 2009). In several nonhuman primates (e.g., rhesus monkey) a significant proportion of the CST fibers project to the ventral horn, while muscle groups that are especially crucial for dexterity, and hence functional recovery (e.g., hand muscles), are innervated by axons that synapse directly with spinal motor neurons (Lemon et al.,2004; Riddle et al., 2009). In fact, it has been found that the higher the number of direct connections between neocortex and motor neurons, the higher the level of manual dexterity in nonhuman primates (Lemon et al., 2004), something that is even more marked in humans (Kuypers, 1964).

The neocortex of humans and nonhuman primates, which gives rise to the CST, has massively increased over the course of evolution. The CST axons have moved from the dorsal to the lateral columns of the spinal cord, and the CST has developed a fast-conducting component (Rouiller et al.,1996), expanding the gap between rodents and primates and potentially explaining some of the altered responses to injury. Contrary to the complex projection pattern of the CST in primates to control voluntary movement, the CST in rodents projects mainly to dorsal horn neurons and premotor spinal circuits and is not necessary for non-complex movement execution. After CNS injury, it has been found that synaptic reorganization of the spared CST fibers is possible in an attempt to bridge the perilesional area and restore fine movement control capabilities in humans and nonhuman primates, but not in rats (Friedli et al., 2015). Accordingly,the use of rodents would not suffice for evaluating the restoration of fine motor skills and voluntary movements after an injury. In regard to reliable assessment of functional recovery and clinical progress of the subject after a tested intervention through functional clinical scales, the stepping-related spinal circuitry is of utmost significance. Nevertheless,supraspinal input might play a much more significant role in the activation of that circuitry in nonhuman primates compared to lower order mammals (C?té et al., 2016), making the interpretation of the functional results much less relevant to clinical translation of the treatment.

In addition, it should be pointed out that stimulation of CST neurons in the motor cortex elicits markedly different motor responses not only between primates and rodents(Lemon and Griffiths, 2005), but also among different primate species (Lemon et al., 2004). Therefore, preclinical results should always be interpreted with caution before proceeding with the clinical translation pipeline. Areas associated with adult neurogenesis are no different, given the important cytoarchitectural differences between primate and rodent brains in such regions (Brus et al., 2013). Finally,certain structural and functional brain areas, like the frontal and temporal poles, appear to be unique to primates (Tsujimoto et al., 2011; Insausti, 2013; Buckner and Margulies,2019), while differences are also present in spinal cord anatomy (Courtine et al., 2007).

Behavioral differences

In terms of behavior patterns, humans and Old World monkeys commonly used in neuroscience research (e.g.,rhesus monkeys), have some significant similarities in lifestyle (e.g., diurnality, terrestriality, omnivory), sensory-perceptual abilities, anatomical specializations (e.g., use of hands and thumbs for tactile perception), and genetics.These similarities are reflected in brain organization as well(Krubitzer, 2007).

A highly relevant example for functional recovery in human patients regards the ability of some primates, in contrast to rodents, to control distal hand muscles to accomplish precision grip (Lawrence and Kuypers, 1968; Galea and Darian-Smith, 1997; Vilensky and O'Connor, 1998). There is even evidence suggesting that an increased number of direct cortical projections to spinal musculature signifies increased dexterity and that these projections are the ones that facilitate precision grip in certain primates (Tuszynski et al., 2002). Behaviorally speaking, nonhuman primates and humans are more similar to one another than to rodents,and their commonalities are much more profound in CNS lesions where the motor circuit plays a major role. In specific, unlike rodents (Lawrence and Kuypers, 1968; Lacroix et al., 2004; Lemon and Griffiths, 2005), primates, and especially humans (Nathan and Smith, 1982), rely on intact cortical projections to the spinal cord for maintaining fine motor control of the extremities. In addition, stepping is crucial for assessing motor recovery, and this function is minimally impaired after CST lesions in rodents (Rosenzweig et al., 2009),indicating that the motor cortex is not essential for sustaining simple locomotion in rats or mice. By contrast, it is wellknown that in humans, CST damage leads to severe motor impairment that can be detrimental for the individual, compromising independent walking (Nathan and Smith, 1982).Similar to humans, damage to the CST in rhesus monkeys also significantly affects stepping, resulting in permanent deficits (Rosenzweig et al., 2010; Friedli et al., 2015).

Given the similar behavioral patterns and functions in humans and nonhuman primates, testing nonhuman primates may lead to more accurate prediction of potential therapies after CNS lesions in order to mediate recovery of manual dexterity and stepping. Not only can functional assessments be highly detailed and comprehensive in nonhuman primate models, but they can also correlate closely with human functional assessments. Fine motor control of the forelimb in nonhuman primates involves the precision grip, pre-shaping of the hand, grasping and other manual prehensile tasks performed by macaques and other Old World monkeys. All of these behaviors can be assessed in detail and quantified with direct association to similar tasks performed by humans. Although fine motor control of the forelimb can also be tested in rodents, with CST lesions affecting this function (Blesch and Tuszynski, 2003), the assessments are much less refined.Finesse in digital control is far less developed in rodents compared to nonhuman primates and humans, and the musculoskeletal system of the limbs is markedly different.Another important assessment of locomotor function for human applications is bipedal walking (Larson, 2018), which is possible only in primates. Manually or robotically assisted bipedal step training after SCI is also possible in experiments with nonhuman primates, but not rodents.

Considered together, these behavioral differences strongly suggest that nonhuman primate disease models are an essential step in the path toward clinical translation, especially when the motor circuit is the impaired system. It is also highly important that assessment of cortical connectivity, supraspinal access to spinal motor neurons and segmental circuit properties can be performed in a similar way in nonhuman primates and humans. Multimodal analysis with the use of transcranial magnetic stimulation, magnetic resonance imaging and measurement of sensory-evoked potentials can provide additional value, supplementing the results with motor performance data from nonhuman primate models similar to that obtained from humans.

Figure 1 Illustrative demonstration of the, to date, “unbreakable wall” of nerve repair for central nervous system (CNS) disorders.

Figure 2 Depiction of cell therapies currently being used for stroke in clinical trials based on ClinicalTrials.gov-registered studies and inclusion of next generation cell therapy applications that hold promise and might be implemented in future clinical trials, given advances in neurosciences, neural tissue engineering and nanotechnology.

Figure 3 Endogenous and exogenous mechanisms of action of neural stem cells (NSCs).

Figure 4 Advantages and scalability of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs)-derived exosomes.

Figure 6 Illustrative demonstration of brain mass and total number of neurons for the mammalian species examined to date with the isotropic fractionator.

Figure 5 Ideal translation pipeline contradicting current research practices.

Key differences that could affect neuroregeneration and functional outcomes

It is important to realize that even when functional outcomes appear quite similar in rodents and primates used for clinical translation purposes, the pathophysiology and anatomy involved may be markedly different, limiting the potential for generalization. Even for the simplest skilled movements,primates engage much more complex neural circuits of the parietal and frontal lobes in the cerebral cortex, contrary to what occurs in rodents. Thus, although specific functional improvements might seem similar in primates and rodents,they could have a different neurological basis, ultimately affecting interpretation and potential for translation.

For example, in animal models with an incomplete SCI lesion, the enhanced neuroplasticity and recovery observed in primates compared to rodents can be explained due to the reliance of primate models on the cortex for maintaining motor function. This allows for spared descending CST fibers to “rewire” after incomplete SCI. In conjunction with, e.g., a regenerative treatment or physiotherapy, this characteristic of primates can lead to positive functional outcomes, given the more efficacious neuroplasticity compared to the rodent models. Therefore, targeting neuroprotection and neural plasticity could possibly lead to even better results in such a case. In addition, the fact that new synapses are formed after an injury and the spared fiber tracts can be reorganized at multiple sites in the brain to maximize function and compensate for the lack of mobility in incomplete injuries (Belci et al., 2004), is important to consider for data analysis and assessment of outcomes after a regenerative therapy is tested. It is crucial for the analysis to include adjacent areas of the cerebral cortex and other fiber tracts (Jones and Adkins,2015; Seitz and Donnan, 2015) in order to accurately interpret restorative outcomes in primate models. In addition, targeting restoration of sensory function for improving mobility by inducing regeneration of a few ascending fibers across the injury site is something that would not be as impactful in rodents. Sensory discrimination is much more critical for manual dexterity in primates, potentially leading to a more significant change that could improve mobility and functional outcomes (Darian-Smith and Ciferri, 2005). Knowing the unique characteristics of each species involved in the translation pipeline allows for scientific questions to be more focused and results interpreted more appropriately.

Although, qualitatively speaking, the cascade of events after CNS injury is highly similar in rodents and humans,the rodent species-specific neurobiological regenerative profile is markedly different (Kaplan et al., 2015). In particular,after CNS injury in both rodents and humans, degenerative processes such as vascular response, inflammation, demyelination, axonal degeneration, glial scar, cyst formation (in rats but not mice), and Schwann cell response are observed,as well as regenerative processes such as axonal sprouting,remyelination, and plasticity of uninjured systems. For example, after SCI, cytokine expression has been found to be similar in humans and rodents (Kjell and Olson, 2016; Du et al., 2017). In addition, angiogenesis in the injured human spinal cord appears to develop over a similar time frame as in injured rodents (Kakulas, 2004; Norenberg et al., 2004).

In terms of the regenerative processes, in humans there is some evidence of endogenous regeneration in the injured spinal cord, just as observed in animals, most clearly in sensory afferents. Tator (1998) has reviewed this phenomenon of spontaneous recovery. Neuroplasticity is observed both in humans and animal models. Plasticity has been observed in spinal cord circuitry, and the plastic changes may include growth of sensory fibers (Filipp et al., 2019). Another interesting aspect is that not only spinal cord circuitry, but also cortical circuitry shows plastic changes and reorganization in humans with SCI (Filipp et al., 2019). Remyelination by Schwann cells is another regenerative process shown to occur in humans with SCI, and also in the animals used in preclinical research. Rodents and primate species demonstrate similarities in terms of the extents of spontaneous axonal sprouting, alterations in the extracellular matrix,activation of glia, and migration of Schwann cells into injury sites (Fawcett and Geller, 1998; Beattie et al., 2000; Orr and Gensel, 2018; Alizadeh et al., 2019). Another example of how similarly rodent CNS neurons react to injury is that the regeneration associated genes growth associated protein 43 and c-Jun are transiently expressed in Clarke's nucleus after SCI just as in humans (Schmitt et al., 2003).

Nevertheless, certain differences at the molecular level differentiate the microenvironment around CNS lesions in different species. Some examples of such differences that set humans apart in terms of the reaction after CNS injury are the prolonged Wallerian degeneration, less pronounced inflammation, less extensive glial scar formation, extensive Schwannosis, and the prolonged presence of myelin-associated glycoprotein. These differences can lead to different functional outcomes. With specific regard to the degenerative processes that differ in humans, the astroglial response is markedly delayed and reduced compared to rodents, and only a mild astroglial scar develops (Puckett et al., 1997; Buss et al., 2004). In addition, chondroitin sulphate proteoglycans, which are known outgrowth-inhibitory molecules, are expressed after SCI in humans, but are associated primarily with other cells such as Schwann cells and not astrocytes(chondroitin sulphate proteoglycans are detected mainly in blood vessel walls) (Bruce et al., 2000). Schwannosis and Wallerian degeneration are highly pronounced in humans,but much more limited in rodents. In fact, Wallerian degeneration can be found years after injury in humans (Buss et al., 2004, 2005). One of the most significant degenerative differences that affect the translatability of tested interventions from rodents to humans is the lack of cyst formation in mice contrary to what happens in humans and in rats; given the fact that the cyst is responsible for the cascade of events that result in functional challenges in patients, mice do not undergo similar processes (Hagg and Oudega, 2006).

Thus, although different species undergo similar pathophysiological processes after CNS injury, the anatomical and size-related differences stressed in this article, as well as the potential differences in the extent of secondary damage caused by mechanisms such as cytokine activation (Fitch and Silver, 1999; Alizadeh et al., 2019), support a continued need to study primate models.

Restorative Outcomes Assessments to Encourage Clinical Translation

Even if the correct questions are being asked, the methodology for the regenerative treatment in question is robust,and the best preclinical models have been used in the “rodent-monkey-human” pipeline, there is still one crucial step that can impede clinical translation. This regards the quantitative effect of the regenerative therapy, the measurement of the functional outcomes and the progress of the subjects, as well as the objectivity and reproducibility associated with the treatment.

The state-of-the-art methodology for assessing functional outcomes following a CNS intervention entails standardized and widely used clinical scales. Scales for stroke functional assessment include the Scandinavian Stroke Scale, Barthel Index, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale, and modified Rankin Scale (Theofanidis, 2017; Zietemann et al.,2018), whereas for SCI the American Spinal Injuries Association impairment scales for sensory and motor function (Ellaway et al., 2011) are widely employed. Such scales, which rely on the acumen of the examiner and his or her level of expertise, are used to assess functional recovery in clinical trials. At the same time, similar modified scales are used for preclinical models (e.g., modified neurological severity scores for stroke (Tang et al., 2018) or Basso, Beattie, Bresnahan Locomotor Rating Scale for chronic SCI) (Gianaris et al., 2016) with similar limitations. In order to quantify reparative functional outcomes and accomplish reliability and reproducibility at a worldwide level, which is crucial for clinical translation, these scales need to be supplemented by non-invasive, objective and reliable neuroimaging parameters to provide new, more comprehensive scales.

A vast variety of brain tissue parameters (i.e., biophysical parameters, size and brain structure) can be characterized based on architectural and connectional factors, using current structural imaging techniques (Kim et al., 2010; Schmierer et al., 2010; Wen et al., 2014). By contrast, functional image analysis can further explore connectivity and evaluate motor circuitry from a functional perspective (Li et al., 2014a, b;Stephan et al., 2015), supplementing the structural results.Therefore, by including assessment of the gray and white matter, the structural, functional and behavioral effects of a therapeutic intervention can all be combined in an imaging-based scale that objectively and non-invasively quantifies plasticity,regeneration and repair before and after an intervention for CNS injury is tested. If all these parameters are studied in nonhuman primate models, while being coupled with biological markers of neural plasticity (e.g., synaptophysin as a marker of synaptic density), neuroregeneration (e.g., quantitative analysis of c-Fos as a marker of cell activation, synaptophysin as a marker of synaptic density, quantitative analysis of 5-bromodeoxyuridine positive neural progenitor cells in the subventricular and subgranular zones as a marker of cell proliferation) and inflammation (e.g., cerebrospinal fluid and blood inflammation-related markers), the outcomes could be even more valuable for developing a holistic scale with functional, neuroanatomical and biological bases. This could facilitate the future use of solely non-invasive methodologies in animals and humans to accurately characterize the CNS tissue condition in an objective, quantitative way.

Not only can the benefit of a treatment be quantified effectively this way, along with assessment of clinical progress, but also the therapeutic intervention itself can be tracked non-invasively in real time to better understand its mechanisms of action and allow for future improvements. For example,certain hydrogels have already been visualized with imaging modalities (Cook et al., 2017), tracking their degradation rate to quantify their contribution to the structural repair of the lesion and consequent functional neurological improvements,thereby enabling modifications of the therapeutic methodology based on real-time feedback. Even stem cells can be traced by utilizing nanotechnology to allow for imaging modalities to track their trajectories, thus gaining in-depth understanding of the mechanisms of action for the development of future targeted treatments (Nicholls et al., 2016).

In addition, image analysis can contribute to the clinical translation pipeline with well-informed brain atlases for several different species (Makris et al., 1999, 2010), potentially enabling the establishment of structural and functional links between species. This could allow for more effective tailoring of therapeutic protocols when moving from rodents toward larger mammals and ultimately humans, thus minimizing safety risks, maximizing therapeutic potentials, and accelerating the translation path.

Conclusions and Future Directions

Neuroregeneration and neural tissue engineering are highly promising research fields that keep moving medicine forward in ways that scientists could not have predicted years ago, challenging common knowledge (i.e., the inability of the CNS to regenerate).

Several hydrogel matrices potentially suitable for CNS repair applications and with translational potential have already been developed. The structural support, the nourishing effect and the tunability that a biocompatible hydrogel has to offer could be utilized in the future to enhance the therapeutic effects of promising regenerative therapies. A suggested combination for future study could be the use of such a hydrogel system with MSC-derived exosomes in an attempt to safely retain the exosomes in the lesion site for periods of time that would be adequate for effective nerve repair. This could take advantage of a nanoscale acellular delivery system, which would maintain the positives and avoid the negatives of cell-based therapies, while maximizing the therapeutic impact due to coupling with the hydrogel system. Nevertheless, successful clinical translation of any pioneering strategy does not rely solely on novel methodologies and revolutionizing tools.

The prerequisites for successfully translating a promising novel therapeutic strategy are: 1) the hypothesis needs to be correct and to the point in terms of clinical significance to maximize the impact; 2) the developed methodology needs to be robust, reliable and reproducible so that the intervention can be safely and effectively applied globally; 3) the results need to be validated in a nonhuman primate model appropriate for the condition being studied, after taking into account potential interspecies differences that might affect translatability; and 4) the assessments for restoration of function need to be both qualitative and quantitative, relying not only on highly subjective clinical functional scales, but also on objective and reliable scales guided by advanced image analysis.

There is much more progress needed for these conditions to be met and solutions to the currently unsolved problem of CNS repair to be found. There are also challenges that should be taken into consideration before considering any regenerative therapy as panacea for CNS repair. For example, even though the discussed regenerative therapeutics attempt to resolve the ineffective CNS nerve repair within the hostile micro-environment of the CNS, and could well be implemented in damaged CNS tissue regardless of causation,certain underlying neurodegenerative conditions should be taken into account when implementing such treatments given potential pathophysiological changes that may alter the functional post-treatment outcome. Nevertheless, the incorporation of image analysis tools (e.g., DTI tractography)along with adoption of the suggested “rodent-monkey-human” translation pipeline could move the scientific community in a more productive direction, and maximize the success rates of clinical trials in regenerative neurology.

Acknowledgments:We would like to thank Dr. Douglas Rosene, Dr.Tara Moore and their team at Boston University, USA for sharing expertise on nonhuman primate models, focusing mainly on ischemic stroke.We would like to thank Dr. Edward Yeterian (from Department of Psychology, Colby College, USA), and the anonymous reviewers for providing useful comments on the manuscript.

Author contributions:Review conception and design: MT, KD, NM;data collation, analysis and interpretion: MT, KD; paper writing: MT;specific portions writing and editing: KD; paper review and review guiding: NM. All authors approved the final version of this paper.

Conflicts of interest:The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Financial support:This work was supported by Onassis Foundation (to MT); the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health(NCCIH), No. R21AT008865 (to NM); National Institute of Aging (NIA)/National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), No. R01AG042512 (to NM).

Copyright license agreement:The Copyright License Agreement has been signed by all authors before publication.

Plagiarism check:Checked twice by iThenticate.

Peer review:Externally peer reviewed.

Open access statement:This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak,and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

- 中國神經(jīng)再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- Trophic factors are essential for the survival of grafted oligodendrocyte progenitors and for neuroprotection after perinatal excitotoxicity

- Neuroprotection of Cyperus esculentus L. orientin against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion induced brain injury

- Effect of docosahexaenoic acid on the recovery of motor function in rats with spinal cord injury:a meta-analysis

- Ferrostatin-1 protects HT-22 cells from oxidative toxicity

- Early active immunization with Aβ3-10-KLH vaccine reduces tau phosphorylation in the hippocampus and protects cognition of mice

- The Schlager mouse as a model of altered retinal phenotype