Disability, psychiatric symptoms, and quality of life in infertile women: a cross-sectional study in Turkey

Hacer SEZGIN, Cicek HOCAOGLU*, Emine Seda GUVENDAG-GUVEN

Disability, psychiatric symptoms, and quality of life in infertile women: a cross-sectional study in Turkey

Hacer SEZGIN1, Cicek HOCAOGLU2,*, Emine Seda GUVENDAG-GUVEN3

infertility; quality of life; disability; psychiatric symptoms; cross-sectional study; Turkey

1. Introduction

Infertility, defined as the failure to become pregnant despite regular sexual intercourse for one year, affects 10-15% of couples in the reproductive age group (18-45 years of age).[1]It often results in substantial negative social and psychological effects for the affected couple,particularly the woman.[2-4]There are many studies about the etiology and treatment of infertility[5-7]but relatively few about the psychological and social effects of infertility.

One study of 112 women being treated for infertility in Taiwan[8]reported that 23% met diagnostic criteria for an anxiety disorder, 17% for major depressive disorder, and 10% for dysthymic disorder; thus over 40%had one of these common mental disorders, a much higher prevalence than the 10% to 12% reported in the general population. Nationally representative studies of community-dwelling women in the United States,[9]and in Finland[10]reported that infertility was associated with high rates of anxiety symptoms.

Social factors influence attitudes about infertility and the lived experience of persons who are infertile.Thus, it is reasonable to expect that the prevalence of mental disorders in individuals with infertility will vary cross-culturally. The aim of this study was to compare the severity of anxiety, depression, and diminished quality of life between married women from one urban center in Turkey seeking treatment for infertility with that of fertile married women from the same community who are matched for age.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

As shown in Figure 1, this study enrolled married women treated in the outpatient clinic of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of the Rize Training and Research Hospital who had a diagnosis of infertility between March and September 2011.Participants met the following criteria: (a) 18 to 50 years of age; (b) currently married; (c) residents of Rize; (d) able to read at a level that made it possible to complete the questionnaires used in the study; (e)not menopausal; (f) did not have mental retardation,dementia, a psychotic disorder, or a history of substance abuse; (g) had not used psychoactive medication in the prior 3 months; and (h) provided written informed consent to participate in the study. The control group were healthy fertile women who were currently married and residents of Rize; they were identified from among hospital workers and relatives of the enrolled patients,matched for age with the identified patients, and provided written informed consent to participate in the study.

2.2. Measurements

All participants were administered a comprehensive demographic data form by the researcher, and selfcompleted three scales: the Turkish versions of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS),[11]the Brief Disability Questionnaire (BDQ),[12]and the Short Form Health Survey (SF-36).[13]

Figure 1. Flowchart of the study

2.2.1 The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)[14]is a 14-item scale (7 about anxiety and 7 about depression)scored on 4-point Likert scales (ranging from 0 to 3)that assesses the severity of depressive and anxiety symptoms in the prior week. The total score for each of the two subscales, respectively) ranges from 0 to 21,with higher scores representing more severe depression or anxiety. Based on studies with the Turkish version of the scale,[11]individuals with scores of 8 or above on the depression subscale have clinically significant depression and individuals with scores of 11 or more on the anxiety subscale have clinically significant anxiety.

2.2.2 The Brief Disability Questionnaire

The Brief Disability Questionnaire (BDQ) is composed of 11 items about physical and social deficits in the prior month that were originally part of the MOS Short Form General Health Survey.[15]Items are scored on 3-point Likert scales (0 to 2), so the range in scores is from 0 to 22 with higher scores representing greater deficits:scores of 0 to 4 are classified as ‘no deficit’, 5 to 7 as ‘mild deficit’, 8 to 12 as ‘moderate deficit’, and 13 or higher as‘severe deficit’. The validity and reliability of the Turkish version of BDQ have been assessed.[12]

2.2.3 The Short Form Health Survey

The Short Form Health Survey (SF-36)[15]is a selfcompletion scale developed by the Rand Corporation to assess quality of life. The 36 items are subdivided into 8 subscales that assess physical functioning, physical role performance, pain, general health, vitality (energy),social functioning, emotional role-performance, and mental health. The crude subscale scores are converted to 0-to-100 point scales with higher scores representing better health status. The validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the scale has been assessed previously.[18]

2.3 Statistical Analysis

Data were assessed using the SPSS v16.0 statistical package. Demographic variables and the outcomes of the three clinical self-report scales used in the study in the infertile and fertile groups were compared using Chi-square tests for dichotomous variables, Mann-Whitney U tests for ranked variables, and t-tests for continuous variables from normal populations. Within the infertile group, the relationship of the demographic characteristics of the individuals with the outcomes of the three scales were assessed using correlation coefficients (for continuous variables), Chi-square tests,and the Mann-Whitney U test.

The conduct of this study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee in the Faculty of Medicine at Recep Tayyip Erdogan University.

3. Results

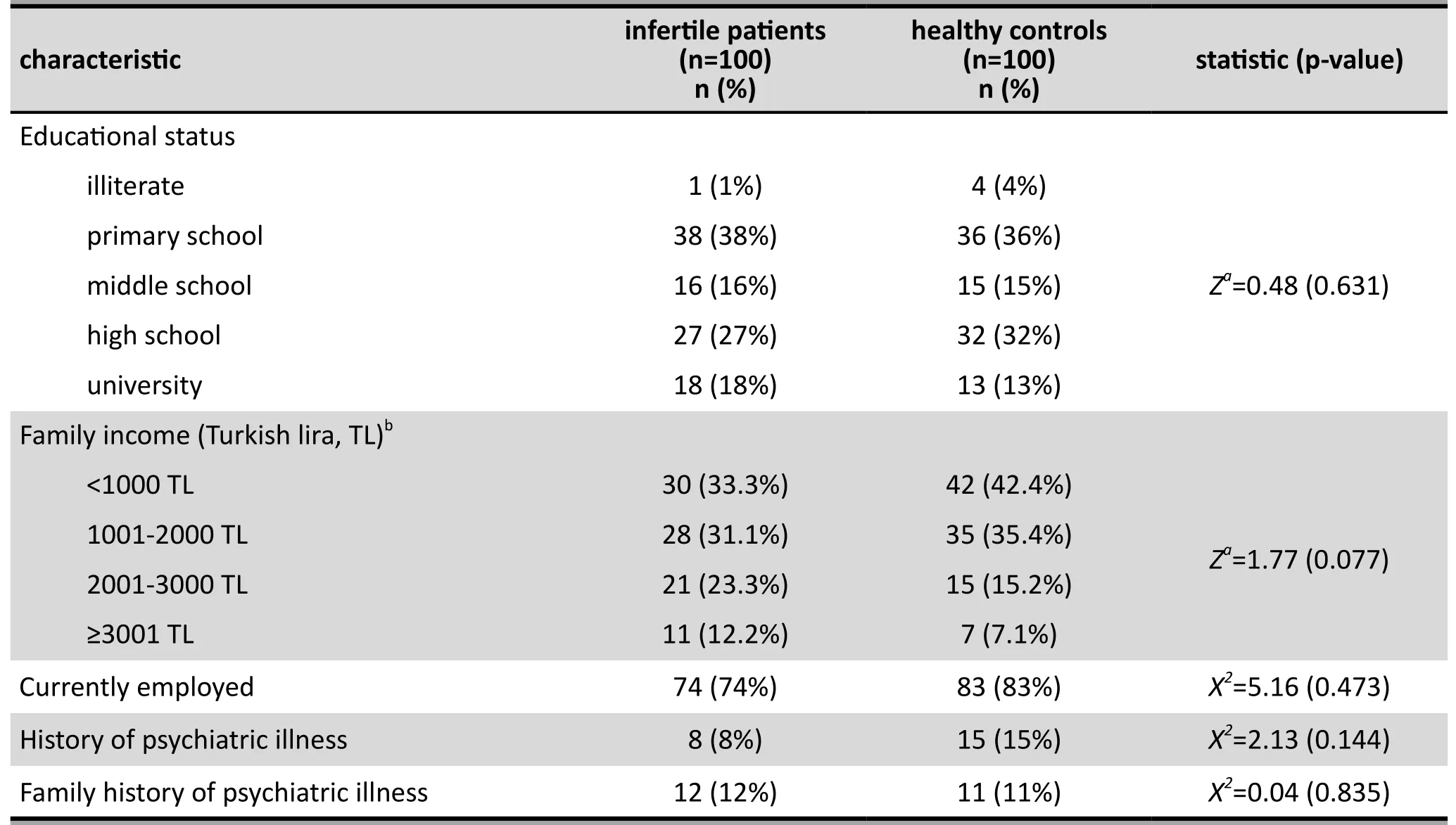

In total, 100 infertile women and 100 healthy volunteers completed the study. Table 1 compares the demographic characteristics of the two groups. There were no significant differences in the level of education or family income between the infertile and fertile women, in the proportion who were currently employed, or in the proportions who reported a personal or family history of psychiatric treatment. The range in age of individuals in the infertile group was 21 to 47 and that of individuals in the control group was 22 to 52. The mean (sd) age of individuals in the infertile group was 29.7 (5.6) years and that in the fertile control group was 30.7 (5.5) years(t=1.27, p=0.204). There was, however, a significant difference in the duration of marriage between groups:the infertile group had been married for an average of 9.3 (6.3) years while the healthy control group had only been married for an average of 6.4 (3.4) years(t=4.05, p<0.001). Among the 8 women in the infertile group with a history of psychiatric illness, 5 had had major depression, 2 panic disorder, and 1 somatization disorder; the 11 women in the healthy control group with a history of a psychiatric disorder included 6 who had had major depression, 3 with generalized anxiety disorder, 2 with adjustment disorder, and 1 with obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Comparison of the anxiety and depression subscale scores of the HADS, BDQ total scores, and SF-36 subscale scores between the two groups is shown in Table 2. The mean level of self-reported anxiety and depressive symptoms over the prior week was not significantly different between the two groups. However,the proportion of subjects who had clinically significant anxiety (i.e., HADS anxiety subscale score >11) was significantly higher in the infertile group than in the control group (31% v. 17%, X2=5.37, p=0.020) and the proportion who had clinically significant depression (i.e.,HADS depression subscale score >8) was also higher (but not significantly higher) in the infertile group than in the control group (43% v. 33%, X2=2.12, p=0.145).

The severity of self-reported disability was significantly greater among infertile patients than among the fertile controls. The proportion of respondents in the infertile group classified as ‘no disability’, ‘mild’disability’, ‘moderate disability’ and ‘severe disability’were 5%, 15%, 63%, and 17%, respectively; the corresponding proportions in the fertile control group were 39%, 39%, 20% and 2%, respectively. (Z-value for the Mann-Whitney rank test=7.82, p<0.001).Comparison of the scores of the various measures assessed by the SF-36 show that 4 of the 8 subscales –general health, vitality, social functioning, and mental health – were significantly worse in the infertile group.

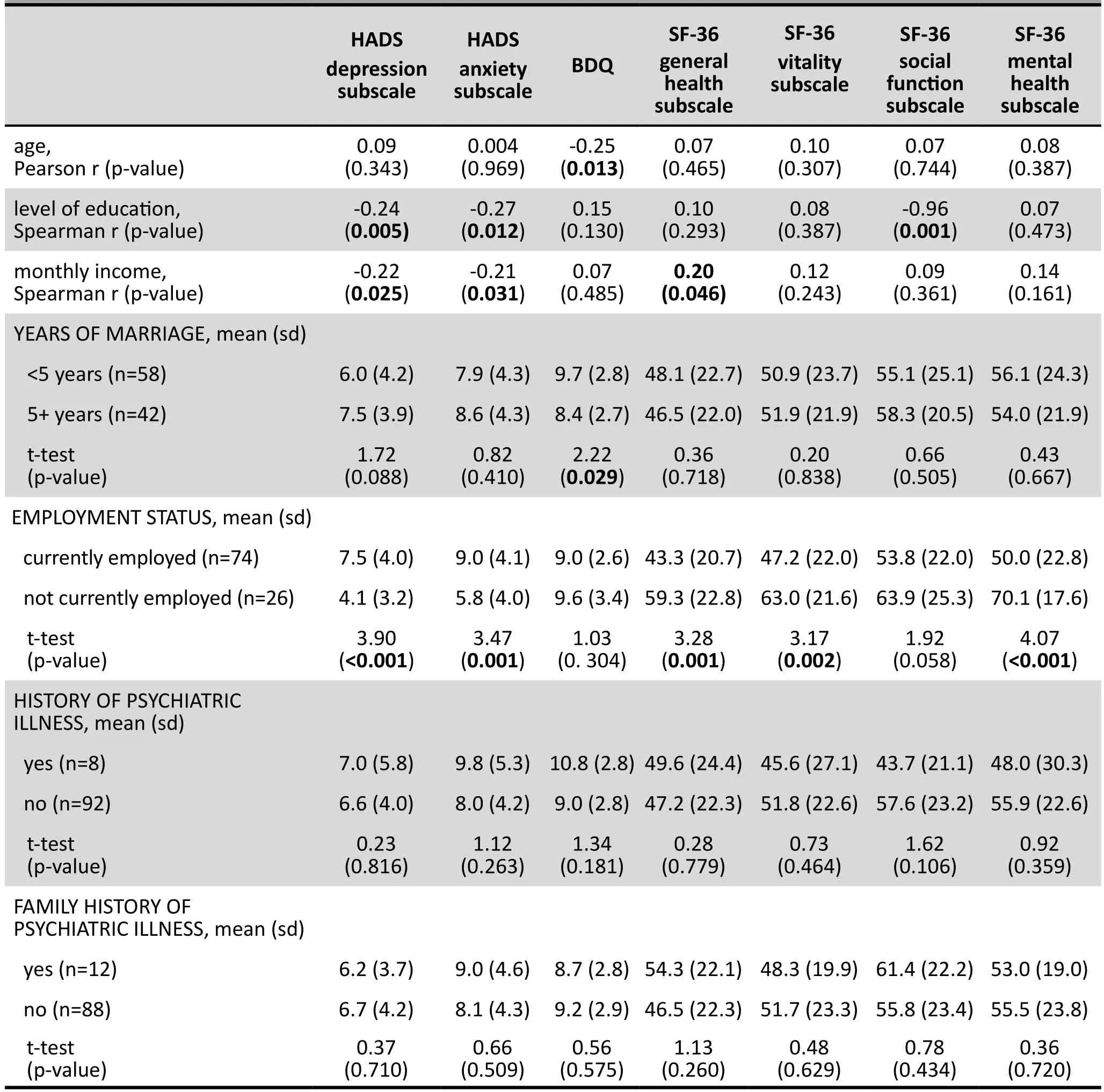

Table 3 shows the association between different demographic characteristics of the infertile patients and the severity of their depressive and anxiety symptoms,their self-reported level of disability, and their scores on the four SF-36 subscales in which the infertilepatients were functioning at significantly lower levels than controls. There were several significant findings.AGE: somewhat unexpectedly, within this group of infertile women, self-reported disability decreased with age. EDUCATION: higher education was significantly associated with decreased self-reported depression and anxiety, and poorer self-reported social functioning.INCOME: higher family income was associated with less severe self-reported depression and anxiety, and better self-reported general health. DURATION OF MARRIAGE:infertile women married for less than 5 years reported significantly greater disability over the prior month than infertile women married for 5 years or more. CURRENT EMPLOYMENT: compared to employed infertile women,unemployed infertile women had less severe depressive and anxiety symptoms and reported better general health, vitality, and mental health. Neither a HISTORY OF PSYCHIATRIC ILLNESS nor a FAMILY HISTORY OF PSYCHIATRIC ILLNESS were significantly related to any of the outcome variables.

Table 1. Comparison of socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of infertile female patients and healthy,fertile controls

Table 2. Mean (sd) scores from the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), the Brief Disability Questionnaire (BDQ), and the Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) of 100 infertile female patients and 100 fertile controls from Turkey

Table 3. Association of demographic variables and scores of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scales(HAD-D, HAD-A), the Brief Disability Questionnaire (BDQ), and three subscale scores of the Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) in 100 infertile female outpatients in Turkey

4. Discussion

4.1 Main findings

Both self-report depressive symptoms and self-report anxiety symptoms on the HADS were more severe in infertile women than in fertile women, but the difference was not statistically significant for depressive symptoms and only statistically significant for anxiety symptoms when results were dichotomized into those with and without ‘clinically significant anxiety’.Infertile women reported greater disability on the BDQ and poorer functioning on 4 of the 8 components of quality of life assessed by the SF-36. We also found that compared to infertile women who were not employed,those that were employed reported more severe symptoms of depression and anxiety, greater disability,and poorer quality of life.

In Turkey, infertile women who are not able to bear children are marginalized in the society and often harshly criticized by their husbands and inlaws. This environment would reasonably be expected to negatively affect the emotional status of infertile women, and, thus, lead to an increased prevalence of common mental disorders, such as depression or anxiety. Most international studies[8,9,16-19]support this hypothesized causal link between a chronic psychosocial stressor and emotional dysregulation: they report a significantly higher severity of depressive and anxiety symptoms and a significantly higher prevalence of depressive and anxiety disorders among infertile women than among fertile women. There are, however,exceptions: similar to the results of the current study,two previous studies from Turkey[20,21]reported no significant difference in the level of depression and anxiety between infertile and fertile women. Previous reports have also had different findings about the association of age and the severity of depression and anxiety symptoms in infertile women; some studies confirm our finding of no relationship,[22,23]while other studies[17,19,20]report that depressive and anxiety symptoms increase with age. The reason for these differences are unknown, but the possible explanations include (a) high levels of depression and anxiety in all married Turkish women regardless of fertility status; (b)cross-cultural differences in the mechanism via which social stressors lead to emotional disturbances; and (c)methodological limitations of the study,

Several studies have reported on the quality of life among infertile women.[24-35]Similar to our findings,most of the case control studies report substantially decreased quality of life among infertile women in several of the quality of life subscales.[31]However, unlike other studies, we did not find that decreased quality of life among infertile women was closely associated with increased symptoms of depression.[36-38]Thus the quality of life changes in our infertile patients in Turkey were not directly related to changes in the severity of their psychological symptoms.

Our results related to self-reported disability in the month prior to the interview were quite robust. Both the mean score to the BDQ and the ranked classification of the results of the BDQ found that the infertile patient group reported significantly greater impairment than that reported by women of the same age and marital status who were not infertile. In the absence of differences in the level of depressive and anxiety symptoms between the groups, this suggests that social discrimination of women in Turkey who cannot fulfil this expected role directly affects their functioning. To our knowledge, no previous study has reported the level of disability among infertile subjects.

The reasons for the more prominent depressive and anxiety symptoms and greater impairment in the quality of life among employed women who are infertile compared to that in unemployed women who are infertile are unknown. Presumably this is related to the greater exposure employed women who are infertile have to social disapproval than unemployed women(who primarily work in the home as housewives), but further qualitative studies will be needed to clarify this issue.

4.2. Limitations

This study has several limitations. (a) The cross-sectional nature of the study made it impossible to identify causal relationships between infertility and the various psychological, functional, and quality of life measures assessed. (b) All measures employed were selfrated, so different types of reporting biases may have affected the results. (c) There was no formal diagnosis made of the patients or controls so the proportion that had psychological disorders that were severe enough to merit psychiatric intervention was unknown.(d) The sample was selected from married women with infertility being treated at an urban outpatient department, so the results may not be generalizable to all infertile women. (e) Sexual dysfunction, a common problem in infertile couples, was not considered among the eight aspects of quality of life assessed by the SF-36.(f) Several factors that may affect the psychosocial effects of infertility (e.g., duration of infertility, use of different fertility treatments, etc.) were not considered.Finally, (g) the sample of infertile patients was not large enough to employ multivariate linear regression analyses (or other multivariate techniques) to assess the relative importance of potential demographic and clinical treatment determinants of depression, anxiety,perceived disability, or quality of life.

4.3 Importance

This study found that the self-reported level of disability and levels of several measures of the quality of life of infertile married women in Turkey, particularly those who are currently employed, are significantly lower than those of fertile married women. However, the selfreported level of depressive and anxiety symptoms was not different between infertile and fertile women.This disconnect between psychological symptoms,functioning, and quality of life suggests that western assumptions about the causal relation of major psychosocial stressors (such as infertility) to common mental disorders may need to be adjusted when considering non-western cultures, where the meaning and psychological valence of specific types of stressors can be quite different. Only a minority of infertile participants had clinically significant depression (43%)or clinically significant anxiety (33%), so psychosocial interventions for infertile women should focus on social support and place somewhat less emphasis on psychiatric treatment. However, this is a small crosssectional study in one urban clinic in Turkey, so larger studies that enroll a broader spectrum of infertile patients and that follow them over time are needed to confirm the relevance of these findings.

Funding

This study received no financial support.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors report no conflict of interest related to this manuscript.

Ethical review

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Rize, Turkey. (date of approval:25.02.2011; number: 2011/6)

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Authors’ contributions

HS and CH participated in the design of the study,in data collection, and drafted the manuscript. CH performed the statistical analysis and critically reviewed the manuscript. ESGG carried out the clinical diagnosis and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

1. Mosher WD, Pratt WF. Fecundity and infertility in the United States: incidence and trends. Fertil Steril. 1991; 56(2): 192-193

2. Kraft AD, Palombo J, Mitchell D, Dean C, Meyers S, Schmidt AW. The psychological dimensions of infertility. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1980; 50(4): 618-628

3. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Synopsis of Psychiatry. 9th ed.Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003. p. 60-65

4. Raphael-Leff J. Psychotherapy during the reproductive years.In Gabbard GO, Beck JS, Holmes J, editors. Oxford Textbook of Psychotherapy. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. p.367-379

5. Nahar P, Richters A. Suffering of childless women in Bangladesh: the intersection of social identities of gender and class. Anthropol Med. 2011; 18(3): 327–338. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13648470.2011.615911

6. Onat G, K?z?lkaya Beji N. Effects of infertility on gender differences in marital relationship and quality of life: a case control study of Turkish couples. Eur J Obst Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2012; 165(2): 243-248. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2012.07.033

7. Mahlstedt PP. The psychological component of infertility. Fertil Steril. 1985; 43(3): 335-346

8. Chen TH, Chang SP, Tsai CF, Juang KD. Prevalence of depressive and anxiety disorders in an assisted reproductive technique clinic. Hum Reprod. 2004; 19(10): 2313-2318. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deh414

9. King RB. Subfecundity and anxiety in a nationally representative sample. Soc Sci Med. 2003; 56(4): 739-741.doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00069-2

10. Klemetti R, Raitanen J, Sihvo S, Saarni S, Koponen P. Infertility,mental disorders and well-being: a nationwide survey. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010; 89(5): 677-682. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/00016341003623746

11. Aydemir O, Guvenir T, Kuey L, Kultur S. [Reliability and validity of the Turkish version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale]. Turk Psikiyatri Derg. 1997; 8(3): 280-287. Turkish

12. Kaplan I. [The relationship between mental disorders and disability in patients admitted to the semi-rural health centers]. Turk Psikiyatri Derg. 1995; 6(2): 169-179. Turkish

13. Ko?yigit H, Aydemir O, Fisek G, Olmez N, Memis A. [The reliability and validity of the Turkish version of Short Form-36(SF-36)]. ?la? ve Tedavi Dergisi. 1999; 12(3): 102-106. Turkish

14. Aydemir O, Koroglu E. [Clinical scales used in psychiatry].Hekimler Yay?n Birli?i. 2006; 138-139: 346-347. Turkish

15. Stewart AL, Hays RD, Ware JE Jr. The MOS Short-Form General Health Survey: reliability and validity in a patient population.Med Care. 1988; 26(7): 724-735

16. Anderson KM, Sharpe M, Rattray A, Irvine DS. Distress and concerns in couples referred to a specialist infertility clinic.J Psychosom Res. 2003; 54(4): 353-355. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00398-7

17. Domar AD, Zuttermeister PC, Seibel M, Benson H.Psychological improvement in infertile women after behavioral treatment: a replication. Fertil Steril. 1992; 58(1):144-147

18. Lukse MP, Vacc NA. Grief, depression and coping in women undergoing infertility treatment. Obstet Gynecol. 1999; 93(2):245-251

19. Drosdzol A, Skrzypulec V. Depression and anxiety among Polish infertile couples-an evaluative prevalence study. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2009; 30(1): 11-20. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01674820902830276

20. Guz H, Ozkan A, Sar?soy G, Yanik F, Yanik A. Psychiatric symptoms in Turkish infertile women. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2003; 24(4): 267-271

21. Gulseren L, Cetinay P, Tokatl?oglu B, Sar?kaya OO, Gulseren S, Kurt S. Depression and anxiety levels in infertile Turkish women. J Reprod Med. 2006; 51(5): 421-426

22. Ashkani H, Akbari A, Heydari ST. Epidemiology of depression among infertile and fertile couples in Shiraz, Southern Iran.Indian J Med Sci. 2006; 60(10): 399-406.

23. Beutel M, Kupfer J, Kirchmeyer P, Kehde S, Kohn FM,Schroeder-Printzen I. Treatment related stresses and depression in couples undergoing assisted reproductive treatment by IVF or ICSI. Andrologia. 1999; 31(1): 27-35. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0272.1999.tb02839.x

24. Heredia M, Tenías JM, Rocio R, Amparo F, Calleja MA, Valenzuela JC. Quality of life and predictive factors in patients undergoing assisted reproduction techniques. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013; 167(2): 176-180. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2012.12.011

25. Monga M, Bogdan A, Katz SE, Stein M, Ganiats T. Impact of infertility on quality of life, marital adjustment and sexual function. Urology. 2004; 63(1): 126-130. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2003.09.015

26. Fekkes M, Buitendijk SE, Verrips GH, Braat DD, Brewaeys AM, Dolfing JG, et al. Health-related quality of life in relation to gender and age in couples planning IVF treatment.Hum Reprod. 2003; 18(7): 1536-1543. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deg276

27. Hassanin IM, Abd-El-Raheem T, Shahin AY. Primary infertility and health-related quality of life in Upper Egypt. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2010; 110(2): 118-121. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.02.015

28. Abbey A, Andrews FM, Halman LJ. Provision and receipt of social support and disregard: what is their impact on the marital life quality of infertile and fertile couples? J Personality Soc Psychol. 1995; 68(3): 455-469. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.68.3.455

29. Andrews FM, Abbey A, Halman LJ. Is fertility problem stress different? The dynamics of stress in fertile and infertile couples. Fertil Steril. 1992; 57(6): 1247-1253

30. Andrews FM, Abbey A, Halman LJ. Stress from infertility,marriage factors, and subjective well-being of wives and husbands. J Health Soc Behav. 1991; 32(3): 238-253

31. Ragni G, Mosconi P, Baldini MP. Health-related quality of life and need for IVF in 1000 Italian infertile couples.Hum Reprod. 2005; 20(5): 1286-1291. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deh788

32. Weaver SM, Clifford E, Douglas MH, Robinson J. Psychosocial adjustment to unsuccessful IVF and GIFT treatment.Patient Educ Couns. 1997; 31(1): 7-18. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0738-3991(97)01005-7

33. Hearn MT, Yuzpe AA, Brown SE. Psychological characteristics of in vitro fertilization participants. Am J Obstet Gynecol.1987; 156(1): 269-274

34. Onat G, Kizilkaya Beji N. Effects of infertility on gender differences in marital relationship and quality of life: a casecontrol study of Turkish couples. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2012; 165(2): 243-248. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2012.07.033

35. Lau JT, Wang Q, Cheng Y, Kim JH, Yang X, Tsui HY. Infertilityrelated perceptions and responses and their associations with quality of life among rural Chinese infertile couples. J Sex Marital Ther. 2008; 34(3): 248-267. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00926230701866117

36. Smith JF, Walsh TJ, Shindel AF. Sexual, marital and social impact of a man’s perceived infertility diagnosis. J Sex Med.2009; 6(9): 2505-2515. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01383.x

37. Mosalanejad L, Abdolahifard K, Jahromi MG.Therapeutic vaccines: hope therapy and its effects on psychiatric symptoms among infertile women. Glob J Health Sci. 2013; 6(1): 192-200. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/gjhs.v6n1p192

38. Carter J, Applegarth L, Josephs L, Grill E. A cross-sectional cohort study of infertile women awaiting oocyte donation:the emotional, sexual, and quality-of-life impact. Fertil Steril. 2011; 95(2): 711-6.e1. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.10.004

(received, 2016-02-04, accepted, 2016-02-20)

Dr. Hacer Sezgin obtained a medical degree in 2005 from Karadeniz Technical University and received postgraduate training in family medicine between 2010 and 2013 at the Department of Family Medicine at the Medical School of Recep Tayyip Erdogan University in Rize, Turkey. She is currently a specialist physician in the Department of Family Medicine at ?ay?rli State Hospital in Erzincan,Turkey. Her research interests are female infertility and its psychological impact, polycystic ovarian syndrome, diabetes mellitus, insulin resistance, and Hashimoto thyroiditis.

不育婦女的功能障礙、精神病癥狀和生活質量:一項來自土耳其橫斷面研究

Sezgin H, Hocaoglu C, Guvendag-Guven ES

背景:不孕不育是一種重大的生活危機,它可以導致精神病癥狀的發展并且對夫妻的生活質量產生負面影響,但其影響程度可能取決于文化背景。目標:我們比較了土耳其城市中生育婦女和不孕婦女的精神病癥狀程度、功能障礙水平和生活質量。方法:該橫斷面研究納入了100名在里澤教育和研究醫院的婦產科門診治療不孕不育的已婚女性和100名已婚已育的婦女作為對照組。對所有參與者均采用社會人口信息篩查表、醫院焦慮抑郁量表(Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, HADS)、簡單功能障礙問卷 (Brief Disability Questionnaire, BDQ) 和健康狀況問卷 (Short Form Health Survey , SF-36) 進行評估。結果:不育女性的平均焦慮分量表得分和抑郁分量表得分稍高于對照組,但差異無統計學意義。不孕組婦女中有顯著臨床焦慮癥狀的比例(即焦慮分量表得分> 11)顯著高于育齡婦女 (31% v. 17%,X2=5.37, p=0.020),但有顯著臨床抑郁癥狀的比例(即抑郁分量表評分HADS > 8)在兩組間沒有顯著性差異 (43% v. 33%, X2=2.12, p=0.145)。不育女性自我報告前一個月的功能障礙顯著比對照組嚴重,并且不育女性在SF-36的8個分量表中4個(一般健康、活力、社會功能和心理健康)顯著差于對照組。與目前工作的不育女性相比,目前沒有工作的女性不育患者報告的抑郁和焦慮程度較輕,且一般健康狀況、活力和心理健康狀況較好。結論:未發現土耳其城市地區中尋求治療的不孕不育已婚女性并比已婚已育婦女有更嚴重的抑郁癥狀,但他們確實報告有較大的軀體和心理障礙并且生活質量較差。不孕不育的負面影響對在職不孕女性婦女比無業的不孕婦女更嚴重。西方國家這通常報告不孕患者抑郁和焦慮的患病率更高,我們需要更大規模的隨訪研究以評估這些結果與西方國家報告的結果不同的原因。

不育;生活質量;功能障礙;精神病癥狀;橫斷面研究;土耳其

本文全文中文版從2016年8月25日起在

http://dx.doi.org/10.11919/j.issn.1002-0829.216014可供免費閱覽下載

Background:Infertility is a major life crisis which can lead to the development of psychiatric symptoms and negative effects on the quality of life of affected couples, but the magnitude of the effects may vary depending on cultural expectations.Aim:We compare the level of psychiatric symptoms, disability, and quality of life in fertile and infertile women in urban Turkey.Methods:This cross-sectional study enrolled 100 married women being treated for infertility at the outpatient department of the Obstetrics and Gynecology Department of the Rize Education and Research Hospital and a control group of 100 fertile married women. All study participants were evaluated with a socio-demographic data screening form, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), the Brief Disability Questionnaire (BDQ), and the Short Form Health Survey (SF-36).Results:The mean anxiety subscale score and depression subscale score of HADS were slightly higher in the infertile group than in controls, but the differences were not statistically significant. The proportion of subjects with clinically significant anxiety (i.e., anxiety subscale score of HADS >11) was significantly higher in infertile women than in fertile women (31% v. 17%, X2=5.37, p=0.020), but the proportion with clinically significant depressive symptoms (i.e., depression subscale score of HADS >8) was not significantly different(43% v. 33%, X2=2.12, p=0.145). Self-reported disability over the prior month was significantly worse in the infertile group than in the controls, and 4 of the 8 subscales of the SF-36 – general health, vitality, social functioning, and mental health – were significantly worse in the infertile group. Compared to infertile women who were currently working, infertile women who were not currently working reported less severe depression and anxiety and better general health, vitality, and mental health.Conclusions:Married women from urban Turkey seeking treatment for infertility do not have significantly more severe depressive symptoms than fertile married controls, but they do report greater physical and psychological disability and a poorer quality of life. The negative effects of infertility were more severe in infertile women who were employed than in those who were not employed. Larger follow-up studies are needed to assess the reasons for the differences between these results and those reported in western countries which usually report a higher prevalence of depression and anxiety in infertile patients.

[Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2016; 28(2): 86-94.

http://dx.doi.org/10.11919/j.issn.1002-0829.216014]

1Department of Family Medicine, Recep Tayyip Erdogan University School of Medicine, Rize, Turkey

2Department of Psychiatry, Recep Tayyip Erdogan University School of Medicine, Rize, Turkey

3Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Karadeniz Technical University, School of Medicine, Trabzon, Turkey

*correspondence: Dr. Cicek Hocaoglu, Department of Psychiatry, Recep Tayyip Erdogan University School of Medicine, Rize, Turkey.E-mail: cicekh@gmail.com

A full-text Chinese translation of this article will be available at http://dx.doi.org/10.11919/j.issn.1002-0829.216014 on August 25, 2016.

- 上海精神醫學的其它文章

- Treatment resistant depression or dementia: a case report

- Behavioral and emotional manifestations in a child with Prader-Willi syndrome

- Is the DSM-5 hoarding disorder diagnosis valid in China?

- Clinical investigation of speech signal features among patients with schizophrenia

- A community-based controlled trial of a comprehensive psychological intervention for community residents with diabetes or hypertension

- Huperzine A for treatment of cognitive impairment in major depressive disorder: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials