戀愛、交友、閱讀,何以解憂?

By+Germaine+Leece

16世紀的法國作家蒙田說,治愈孤獨有三種可能的方法:戀愛、交友和閱讀。但他進一步闡釋:性愛上的歡愉轉瞬即逝,而背叛稀松平常;友情更佳,卻會隨著其中一方的死亡戛然而止。因此,唯一能伴隨終生的療法就是與文學為伴。原以為閱讀只是逃離自我的一種方式,但其實我們是在探索自己內心深處的世界。

The understanding that literature can comfort, console and heal has been around since the second millennium1 BC. It is no coincidence that Apollo2 was the god of medicine as well as poetry.

As a bibliotherapist, Im interested in the therapeutic value stories have to offer us,3 particularly during times of stress. Here the intent around reading is different; the value of the story lies solely in our emotional response to it.

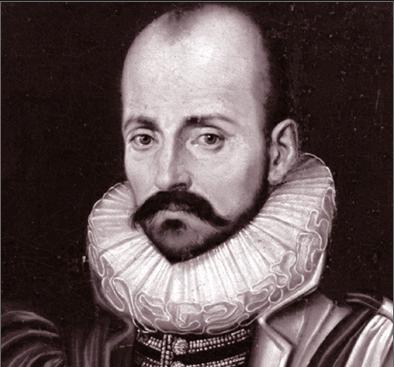

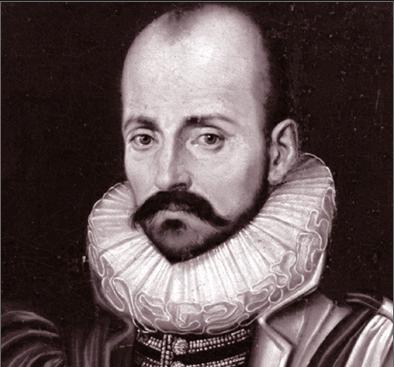

One of the greatest arguments for using literature as therapy was posited by the Renaissance essayist Michel de Montaigne4, who believed there were three possible cures for loneliness: have a lover, have friends and read books. But he argued sexual pleasure is too fleeting and betrayal too common, and while friendship was better it always ended with death. Therefore, the only therapy that could endure through life was the companionship of literature.

Why were the ancient Greeks and Romans right to suppose literature heals the soul? Why did Montaigne trust we could endure loneliness through a lifelong relationship with books? Why, despite all the distractions of modern life, do books still get published and writers festival events get sold out? The answer lies in the power of stories.

Stories have been around since time began; they tell us what it is to be human, give us a context for the past and an insight towards the future. A narrators voice replaces our stressed, internal monologue5 and takes us out of our life and into the world of a story. Paradoxically6, we think we are escaping ourselves but the best stories take us back deeper into our interior worlds. Freud7, who believed the “reading cure” came before the “talking cure”, once wrote that wherever he went he discovered a poet had been there before. It is difficult to access emotional language and this is why we have writers. They remind us of the universality8 and timelessness of emotions, helping us better understand our own.

What stories have shaped you? Its a question worth reflecting on, as this shaping is often subconscious. The act of making it conscious will allow your future reading to perhaps have a different intent; you will be“reading” your life from now on, allowing you to live it more fully and better understand it.

Recently, more studies are telling us what the ancient Greeks and Romans already knew: reading improves our mental health. In 2009, research out of the University of Sussex found reading could reduce stress levels by 68%, working better at calming nerves than listening to music, going for walks or having a cup of tea. Subjects only had to read silently for six minutes to slow down the heart rate and ease tension in muscles.endprint

A 2013 study found reading literary fiction can help you become more empathetic, by giving you the experience of being emotionally transported to other places and relating to new characters. Other studies have shown reading can improve sleep quality and ease mild symptoms of depression and anxiety.

As a bibliotherapist, I am continually reminded that all forms of literature can help people in all sorts of ways. A person who is grieving may need a predictable plot and an ordered fictional world; a man searching for direction or coming to terms with retirement may need a novel that reflects and explores the transience of life; a mother of young children may reach for a novel that illustrates the arc of life and reminds her she is in just one—albeit messy and tiring—chapter for now.9

Sometimes it is not the content of the stories themselves but just knowing you have control by choosing to read or listen that provides the calming effect. All stories offer a safe, contained world with a beginning, middle and end. We have the power of when to start or stop and choose how long we stay in this storys world.

Time spent listening to authors talk about their work and their own understanding of the power of literature also allows us, as readers, to reflect on stories that have shaped us.

“Why do stories matter so terribly to us, that we will offer ourselves up to, and later be grateful for, an experience that we know is going to fill us with grief and despair?” questions Helen Garner in her latest collection, Everywhere I Look.10

Robert Dessaix, in his memoir What Days Are For,11 explores narrative as an “optimistic form”: “Is that why Im reading a novel in the first place? Its not a Pollyannaish form, its not devoid of unravellings and pain,12 but its optimistic in the sense that you keep turning the pages, one after the other… in the hope of something transforming happening. Isnt that it? In the hope of a transforming answer to your particular questions.”

Both authors are exploring their identity as readers and the impact reading can have. The writers festival is more than an event celebrating authors; it also celebrates the power of literature and the power of you, the reader.

文學作品的安撫、慰藉和療愈功效,早在公元前兩千年就為人所知了。難怪太陽神阿波羅被同時尊為醫藥之神和詩歌之神。

作為一名閱讀治療師, 我對文學故事帶來的療愈效果(尤其是在我們倍感壓力時)頗感興趣。處于壓力之下時,閱讀目的是不同的,而故事的價值則僅取決于人們對它的情感反應。endprint

文藝復興時期的散文家蒙田曾提出了將文學作品作為療愈方法的偉大言論。蒙田認為,遏制孤獨感有三種方法:戀愛、交友和閱讀。但他認為,性愛上的歡愉轉瞬即逝,而背叛稀松平常;友情更佳,卻會隨著其中一方的死亡戛然而止,唯一能伴隨終生的療法就是與文學為伴。

為何古希臘人和古羅馬人認為文學能療愈靈魂的觀點是正確的?為何蒙田相信如果我們終身與書為伴,便能忍受孤獨?為何在紛紛擾擾的現代生活中,書籍依舊在出版,作家節活動門票依然售罄?答案都在于故事的力量。

自有時間以來,就有故事。故事告訴我們何為人類,教我們了解歷史,展望未來。敘述者的聲音取代了我們焦慮的內心獨白,讓我們跳出當下的生活,跳進故事的世界。矛盾的是,我們認為閱讀時能逃離自我,但最好的故事卻讓我們更深入自己的內心世界。弗洛伊德認為早在“談話治療”之前便已有了“閱讀療法”。他曾寫道,無論自己去到何處,都會發現這是詩人所到之處。想要掌握情緒這門語言著實困難,所以才有了作家。他們提醒著人們情感的普遍與不朽,幫助人們更深刻了解自己。

哪些故事塑造了你?這一問題值得審慎思考,因為故事對人的塑造通常是在潛意識中進行的。有意識的閱讀行為可能會讓你未來的閱讀目的發生改變;從今往后,你就是自己人生的“閱讀者”,這會讓你更充實地度過自己的一生,并且更好地理解自己的人生。

近來,越來越多的研究證實了古希臘人和古羅馬人的說法:閱讀能改善我們的精神健康。2009年,薩塞克斯大學的一項研究發現,閱讀能減少68%的壓力,在鎮靜安神方面比聽音樂、散步或喝茶更有效。研究對象只需安靜閱讀六分鐘,就能降低心率、緩解肌肉緊張。

2013年的一項研究表明,閱讀文學作品能提高人的移情能力,因為在閱讀過程中,讀者情感轉移至別處,并與作品中新的人物產生聯系。其他研究則顯示閱讀能改善睡眠質量,緩解輕度抑郁和焦慮癥狀。

作為一名閱讀治療專家,我向來知道,不同類型的文學作品能以五花八門的方式給予人們幫助。一個深陷悲痛的人需要沉浸在一個情節老套、有條有理的小說世界里;一個正在尋找人生方向或即將退休的人大概需要讀一本反映、探討生命稍縱即逝的書;一位年幼孩子的媽媽則需要一本闡明人生軌跡的小說,以此來鼓勵自己,當前的生活雖是一團亂麻、讓人心力交瘁,但這只是小說中的一個章節而已。

有時候,并非故事的內容讓人平靜,而是你對于閱讀或聆聽的掌控感讓人安穩。所有故事的開端、高潮和結局,都為讀者提供了一個安全可控的世界:我們可以自己決定閱讀何時開始、何時結束,以及在故事世界里徜徉多久。

花時間聽作家講述自己的作品,以及他們如何理解文學的力量,能讓作為讀者的我們反觀那些影響過自己的文學作品。

作家海倫·加納在她的最新作品集《我目光所及之處》中問道:“為什么故事對我們如此重要,以至于我們明知它會讓我們充滿悲傷和絕望,仍要全身心投入其中,并讀到感激涕零呢?”

羅伯特·德賽在回憶錄《何為歲月》中探討了作為“樂觀主義形式”的敘事:“這就是我會首選看小說的原因嗎?小說敘事并非盲目樂觀,有時候情節還錯綜復雜,讓人痛苦。之所以說它是一種“樂觀主義形式”,是因為你一頁接一頁地翻下去,希望轉機發生。這不就是樂觀主義嗎——期待自己的特定問題會有柳暗花明的答案。”

兩位作家都在書中探索自己的讀者身份,探索閱讀對人的影響。作家日并不只是作家的節日,它還同時歡慶文學的力量和你作為讀者的力量。

1. millennium: 一千年,千年期(尤指公元紀年)。

2. Apollo: 阿波羅,宙斯之子,是古希臘神話中司掌光明、預言、音樂、醫藥 、詩歌等之神。

3. bibliotherapist: 閱讀治療專家;therapeutic: // 有助治療的,有療效的。

4. Michel de Montaigne: 蒙田(1533—1592),法國文藝復興時期人文主義思想家、作家,以《隨筆集》(Essais)三卷留名后世。

5. monologue: 獨白,獨角戲。

6. paradoxically: 自相矛盾地。

7. Freud: 西格蒙德·弗洛伊德(1856—1939),奧地利精神病醫師、心理學家、精神分析學派創始人,著有《夢的解析》(1899年)。

8. universality: // 普遍性,普適性。

9. transience: 轉瞬即逝;albeit: // 雖然,盡管。

10. offer up: 貢獻,奉獻;Helen Garner: 海倫·加納(1942— ),澳大利亞小說家、劇作家。

11. Robert Dessaix: 羅伯特·德賽(1944— ),澳大利亞小說家;memoir: 回憶錄,自傳。

12. Pollyanna-ish: 盲目樂觀的,源于美國作家埃莉諾·霍奇曼·波特1913年創作的系列兒童小說《波利安娜》;be devoid of sth.: 毫無(某特質);unravelling: (對復雜問題的)解釋,闡明。endprint