9~10歲兒童和成人的一致性序列效應*

趙 鑫 賈麗娜 周愛保

9~10歲兒童和成人的一致性序列效應

趙 鑫賈麗娜周愛保

(甘肅省行為與心理健康重點實驗室;西北師范大學心理學院, 蘭州 730070) (天津師范大學心理與行為研究院, 天津 300074)

一致性序列效應是指個體根據前一情境中的沖突信息, 靈活適應當前環境的能力。研究選取9~10歲的兒童和18~25歲的成人為被試, 采用色?詞Stroop任務和Stroop與Flanker刺激混合的任務, 在控制重復啟動的影響后, 考察一致性序列效應在不同任務中的年齡差異。結果發現, 在不同的任務中, 兒童和成人均表現出顯著的一致性序列效應, 且一致性序列效應的大小不存在顯著差異。研究結果表明, 沖突適應過程涉及更高級的加工過程, 9~10歲的兒童已具備類似成人的、更一般化的沖突適應能力。

認知適應; 一致性序列效應; 色?詞Stroop任務; Flanker任務

1 引言

執行功能(executive functions, EFs)是一種較高級的認知加工過程, 在社會生活中起到重要作用(Cao et al., 2013; Lustig, Hasher, & Tonev, 2006; Titz & Karbach, 2014)。在不斷變化的環境中, 執行功能能夠有效的調節個體的適應行為, 進而實現當前目標(Diamond, 2013)。執行功能包括多種不同的子成分, 其中干擾控制是指個體通過調節注意力, 對不相關的刺激或刺激特征進行抑制, 從而做出正確反應的能力(Miyake, Friedman, Emerson, Witzki, & Howerter, 2000)。干擾控制的經典研究范式包括色?詞Stroop任務(MacLeod, 1991)和Flanker任務(Eriksen & Eriksen, 1974), 在這兩項任務中, 當目標刺激和非目標刺激同時出現時, 都要求個體對非目標刺激進行抑制, 進而對目標刺激做出反應。其中, 當非目標刺激與目標刺激涉及相同的反應方式時, 為一致試次; 當目標刺激和非目標刺激引發不同的反應方式時, 則為不一致試次。在不一致試次中, 個體需要抑制對非目標(沖突)刺激的注意以及相應的行為反應。目前大量研究均已證明, 與不一致試次相比, 個體在一致試次下的反應時更快且正確率更高(Egner & Hirsch, 2005; Goldfarb, Aisenberg, & Henik, 2011; Stins, Polderman, Boomsma, & de Geus, 2007)。因此, 研究者將不一致試次和一致試次在反應時和正確率上的差異, 定義為一致性效應, 并用來衡量干擾控制能力的大小, 即干擾控制量。

除通過一致性效應衡量干擾控制外, 另一種衡量方法反映了干擾控制能力的靈活性和適應性。在考察抑制控制能力的任務中, 快速的跨試次適應能力可以通過一致性序列效應(congruency sequence effects, CSEs)的形式觀察到。一致性序列效應, 也稱沖突適應效應或Gratton效應, 最早是由Gratton, Coles和Donchin (1992)通過Flanker任務發現的(Gratton et al., 1992), 之后不同研究者在其他抑制控制的任務中也發現了一致性序列效應(Kerns, 2006; Larson, Clawson, Clayson, South, 2012; Larson, Kaufman, Perlstein, 2009)。一致性序列效應表現為被試在不一致試次之后的一致性效應顯著小于一致試次之后的一致性效應(Duthoo, Abrahamse, Braem, Boehler, & Notebaert, 2014b), 即與一致試次之后的不一致試次相比(簡稱cI試次), 個體在不一致試次之后的不一致試次(iI)中的反應時較快且正確率較高; 或者表現為與不一致試次后的一致試次(iC)相比, 個體在一致試次之后的一致試次(cC)中的反應時較快且正確率較高; 亦或是同時包括上述兩種表現形式(Lamers & Roelofs, 2011)。

目前對一致性序列效應進行解釋的理論至少包括三種(Botvinick, Braver, Barch, Carter, & Cohen, 2001; Gratton et al., 1992; Mayr, Awh, & Laury, 2003)。第一種理論觀點為沖突監測理論(Botvinick et al., 2001), 該理論認為, 當干擾信息出現時, 前部扣帶回皮層(anterior cingulate cortex, ACC)對干擾信號進行檢測, 并進一步激發背外側前額皮層(dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, DLPFC), 以加強認知系統自上而下的認知控制, 進而對認知資源進行調整。當之前的試次為不一致試次時, 相關的大腦皮層區域處于較高的激活狀態, 導致認知控制水平較高。因此在當前的不一致試次中, 認知系統處于積極的準備狀態, 能夠更有效的對沖突進行監測和控制。第二種理論觀點為重復?預期的理論解釋(Gratton et al., 1992), 按照該理論的解釋, 在實驗中, 被試一般會預期連續的兩個試次為同一種類型(同為一致試次或同為不一致試次)。在Flanker任務中, 不一致試次之后, 被試的預期是下一個試次也是不一致試次, 因此注意的范圍會縮小, 并定位于中央的刺激; 相反, 在一致試次之后, 被試會預期下一個試次同為一致試次, 因此注意的范圍會相應的擴大。根據該理論, 這些不同的期望整合在一起, 則構成了一致性序列效應。第三種解釋是基于低水平重復效應的概念(Mayr et al., 2003), 并結合了特征整合或特征啟動的觀點(Hommel, Proctor, & Vu, 2004)。該理論認為并不存在認知適應的過程, 因此也不涉及ACC或DLPFC的參與, 相反, 該理論強調, 在標準的Stroop和Flanker任務中, 當刺激出現時, 認知系統會將相應的刺激特征與反應特征進行整合并存儲在情景記憶中。在下一試次中, 當刺激特征出現重復時, 會激發認知系統在上一試次中整合的模式, 導致反應時較短, 出現了適應效應(Nieuwenhuis et al., 2006)。根據特征整合理論, 反應時上的差異是由于刺激和反應的同時發生自動引發一個短暫的刺激?反應(S-R)聯結。該聯結形式表明, 當再次激活聯結中的某個元素時(S或R), 另一個元素(R或S)也會被激活或啟動。

目前對于一致性序列效應年齡差異的研究, 大多數研究均考察的是成人(Duthoo et al., 2014b; Freitas, Bahar, Yang, & Banai, 2007; Funes, Lupiá?ez, Humphreys, 2010; Jiménez & Méndez, 2013), 而采用標準的干擾控制任務來考察兒童和青少年一致性序列效應的研究則相對較少, 并且這些研究發現, 一致性序列效應早在5歲時就出現了(Ambrosi, Lemaire, & Blaye, 2016; Cragg, 2016; Erb, Moher, Song, & Sobel, 2018; Iani, Stella, & Rubichi, 2014; Larson et al., 2012; Nieuwenhuis et al., 2006; Stins et al., 2007)。然而, 在上述研究中, CSEs是否由低水平的加工過程(即特征整合解釋所提出的)所驅動, 一些研究并沒有有效控制這種可能性(Ambrosi et al., 2016; Iani et al., 2014; Stins et al., 2007); 另外, 一些研究并沒有在同一個實驗中直接比較不同年齡組之間的差異(Ambrosi et al., 2016; Stins et al., 2007); 還有一些研究并未在所有的干擾控制任務中發現穩定的CSEs, 例如, Ambrosi等人(2016)的研究中, 在Stroop和Simon任務中發現了CSEs, 卻沒有在Flanker任務中發現CSEs。因此, 有研究通過實驗設計或事后試次的分離來排除重復啟動的影響(Erb et al., 2018; Larson et al., 2012; Nieuwenhuis et al., 2006)。綜上, 與成人相比, 兒童是否具有相同的適應能力以及相同的認知適應模式, 仍然需要更多的研究來探討。

一致性序列效應是以個體的抑制控制能力為基礎的。有研究表明, 9.6~11.5歲是抑制能力發展較快的年齡階段(Brocki & Bohlin, 2004)。此外, Zhao和Jia (2018)的研究采用改版Stroop任務對平均年齡為10.48歲的兒童進行干擾控制能力的訓練, 結果發現與成人相比, 該年齡階段兒童抑制控制的可塑性更強。據此, 9~10歲可能也是沖突適應能力發展的關鍵期。此外, 9~10歲的兒童在干擾控制任務上的行為表現具有可比性(MacLeod, 1991; Rueda et al., 2004), 但目前研究結論尚不一致(Larson et al., 2012; Waxer & Morton, 2011)。如Waxer和Morton (2011)探討了不同年齡階段的一致性序列效應, 結果發現, 9~11歲的兒童沒有表現出顯著的一致性序列效應。Larson等人(2012)選取21名平均年齡為9.7歲的兒童與26名成年人為被試, 利用Stroop任務探討了一致性序列效應, 結果發現, 兒童能夠表現出顯著的一致性序列效應, 且與成人的一致性序列效應差異不顯著。研究表明, 與認知控制相關的前部扣帶回(ACC)皮層發展成熟要到成年早期(Adleman et al., 2002), 前額皮層(PFC)的發展成熟至少要到青少年時期(Luna & Sweeney, 2004)。因此, 9~10歲兒童執行抑制控制任務所涉及的大腦結構和功能尚未完全成熟(Luna, Garver, Urban, Lazar, & Sweeney, 2004), 兒童所表現出的與成人相似的行為反應, 可能是通過激活其他大腦回路來實現的(Wilk & Morton, 2012)。

如前所述, 兒童在多大程度上能夠表現出與成人類似的靈活適應能力, 有待于更深入的評估。因此, 本研究選取9~10歲的兒童和18~25歲的成人為被試, 探討一致性序列效應的年齡差異。研究包括兩個實驗任務, 任務1為標準的雙選擇色?詞Stroop任務, 其中只分析反應變化的試次, 以控制低水平的加工過程。基于以往的研究(Larson et al., 2012), 我們可以預測, 與成人被試相比, 兒童的反應時較慢且錯誤率較高。然而, 我們主要關注的問題是, 兒童是否能夠表現出與成人類似的一致性序列效應。在任務2中, 通過采用Stroop試次和Flanker試次混合的實驗設計, 來進一步排除低水平加工過程的潛在影響。跨任務的CSEs更能夠有效說明認知控制的適應過程, 因為前一試次與當前試次中涉及的是完全不同的刺激。與單一任務(任務1)相比, Flanker-Stroop任務的難度相對有所增加, 因此對認知控制的要求會提高, 個體需要更多的認知資源來完成當前任務。有研究表明, 在一定的條件下, 在成人被試中發現了跨任務的CSEs (Braem, Abrahamse, Duthoo, & Notebaert, 2014), 而對于兒童, 其相關腦區發育尚不完善(Adleman et al., 2002; Luna & Sweeney, 2004)。由此我們預測, 兒童在跨任務中, 可能無法有效的調整認知資源, 適應沖突的環境。因此, 不同年齡間認知控制能力的差異可能會更顯著(Benikos, Johnstone, & Roodenrys, 2013; Kray, Karbach, & Blaye, 2012)。

2 方法

2.1 被試

33名18~25歲的大學生(19名男生)自愿參加實驗, 平均年齡20.6歲(0.33), 34名來自某小學的9~10歲兒童(16名男生)參加實驗, 平均年齡9.5歲(= 0.09)。根據之前該小學的標準心理測評結果, 所有兒童均不存在精神或神經疾病史。成人被試均簽署了知情同意書, 兒童被試監護人均簽署了知情同意書。所有被試均為漢族、右利手、視力或矯正視力正常, 不存在色盲。實驗結束后給予被試一定的報酬。

2.2 儀器與刺激

實驗任務通過E-prime軟件編寫, 刺激呈現在17英寸的電腦顯示屏上, 被試距顯示屏的距離約60 cm。Stroop任務(任務1)中的刺激為帶有顏色的漢字“紅”和“綠”, 當漢字“紅”的字體顏色為紅色時, 為一致試次, 當漢字“紅”的字體顏色為綠色時, 為不一致試次; 同理, 紅色寫的“綠”為不一致試次, 綠色寫的“綠”為一致試次。任務2中的刺激既包括任務1中的“紅”“綠”漢字, 同時還包括箭頭Flanker刺激。在Flanker任務中, 刺激是由5個箭頭組成, 當5個箭頭同時朝向某個方向時(> > > > > 或 < < < < < )為一致試次, 當中間箭頭的指向與兩側箭頭的方向不同時(> > < > > 或 < < > < < ), 則為不一致試次。所有任務要求被試用左手食指按鍵盤上的“F”鍵, 用右手食指按鍵盤上的“J”鍵進行反應。

2.3 實驗設計與程序

采用2(前一試次一致性:一致c, 不一致i) × 2(當前試次一致性:一致C, 不一致I) × 2(年齡組:兒童, 成人)的混合設計, 其中, 前一試次一致性與當前試次一致性為被試內變量, 年齡組為被試間變量。整個實驗共分兩天進行, 第一天要求被試完成任務1 (色?詞Stroop任務)。為了避免練習效應與疲勞效應, 要求被試回去休息后, 第二天來完成任務2 (Flanker-Stroop混合任務)。

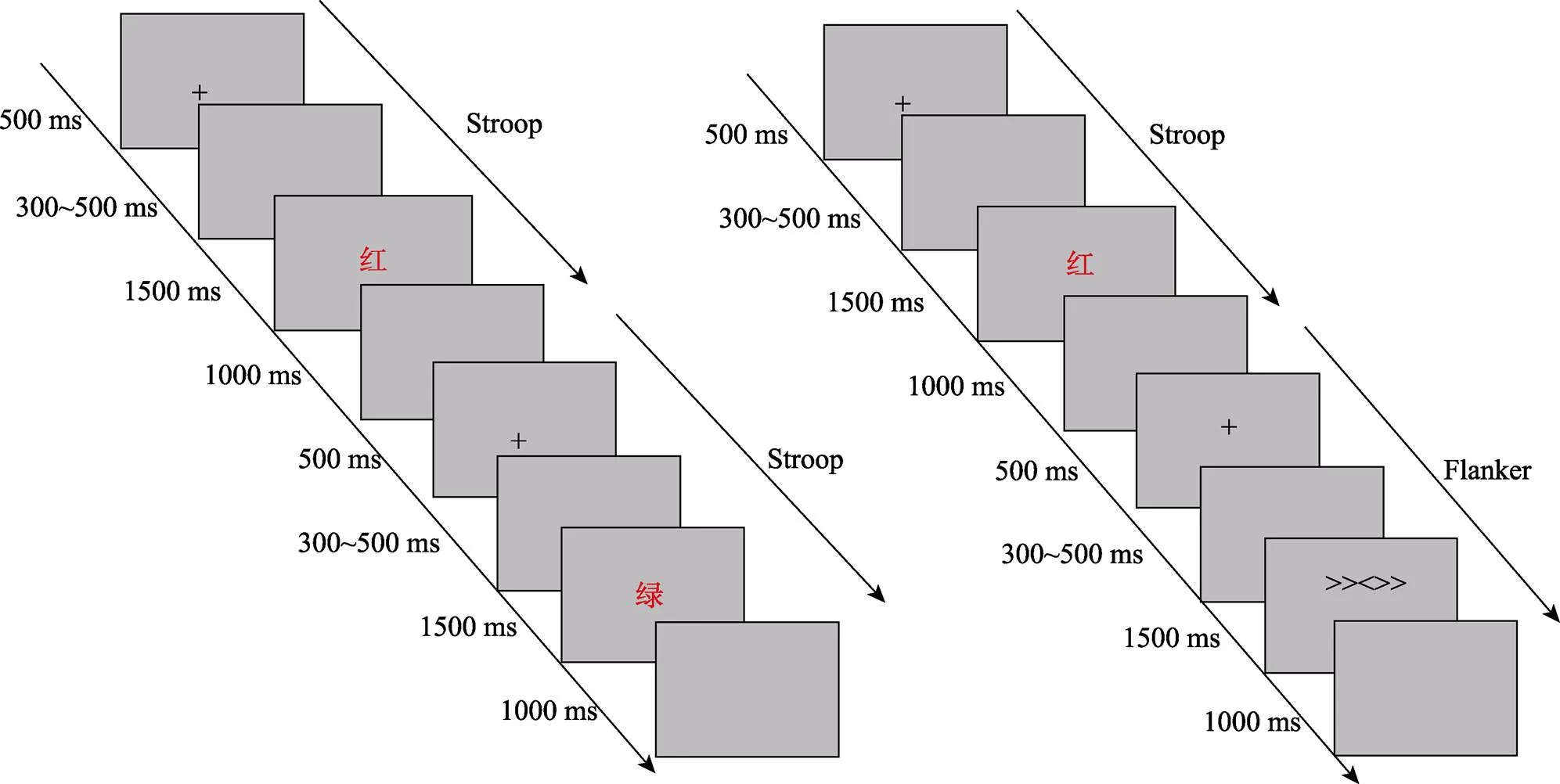

具體實驗流程如下:首先在灰色的屏幕上呈現500 ms的黑色注視點“+”, 然后是300~500 ms的隨機空屏, 之后刺激呈現1500 ms, 被試做出反應后立即消失, 刺激之后是1000 ms的空屏, 接著進入下一試次。任務1中(見圖1左), 始終要求被試對字的顏色進行反應, 如果字的顏色為紅色, 則用左手食指按鍵盤上的“F”鍵進行反應, 如果字的顏色為綠色, 則用右手食指按鍵盤上的“J”鍵進行反應; 任務2中(見圖1右), 當出現箭頭時, 要求被試對中間箭頭的方向進行反應, 而忽略兩側箭頭的方向。如果中間箭頭的方向指向左, 則用左手食指按鍵盤上的“F”鍵進行反應, 如果中間箭頭的方向指向右, 則用右手食指按鍵盤上的“J”鍵進行反應。而當出現顏色詞時, 要求與任務1相同, 即對字的顏色進行反應, 如果字的顏色為紅色, 被試按鍵盤上的“F”鍵進行反應, 如果字的顏色為綠色, 被試按鍵盤上的“J”鍵進行反應。整個實驗要求被試既快又準的進行反應。

實驗程序分為1個練習block和4個正式實驗block, 在練習block中, 為了讓被試熟悉按鍵規則和實驗過程, 練習正確率達到85%后才可以進入正式實驗。任務1中練習block共16個試次, 包括8個一致試次和8個不一致試次。正式實驗每個block有64個試次, 包括32個一致試次和32個不一致試次, 正式實驗共256個試次, 所有試次采用偽隨機的方式排列。每個block結束后有一個休息時間, 休息時間的長短由被試自己控制, 整個任務大約持續15分鐘。任務2是Stroop刺激和Flanker刺激混合的任務, 其中練習block共24個試次, 一致試次和不一致試次的比例相同, 練習正確率達到85%后進入正式實驗。正式實驗每個block包括64個試次, 共256個試次。在每個block中, 包括4個Stroop刺激和4個Flanker刺激。首先呈現任務轉換試次, 接下來為同一任務內的試次轉換, 即前四個試次的呈現順序為Stroop→Flanker→Stroop→Stroop刺激(簡稱SFSS)或Flanker→Stroop→Flanker→Flanker刺激(簡稱FSFF)。之后的試次再次為不同任務的轉換, 構成了不同任務和相同任務間的轉換。采用這種嚴格轉換的目的是強制性的不斷更新任務設置, 從而將與任務設置相關的影響降低到最小, 并加強對不斷變化的認知需求的調整(Wilk, Ezekiel, & Morton, 2012)。整個任務中, 在不同任務轉換(跨任務轉換)時, Stroop→Flanker和Flanker→Stroop試次組合中均包括相等數量的cC, cI, iC, iI試次。每個block間被試可自主休息, 整個任務完成大約需15分鐘。

圖1 實驗流程圖(左:任務1; 右:任務2)

2.4 數據分析

對于任務1, 對反應時和正確率進行重復測量方差分析, 其中年齡組(兒童, 成人)為被試間因素, 前一試次一致性(一致, 不一致)和當前試次一致性(一致, 不一致)為被試內因素。反應時的分析中, 排除反應錯誤的試次、試次之后反應錯誤的試次以及重復正確反應的試次對。最后一種排除標準用于控制重復效應, 根據該標準, 排除了32.2%的試次。然而, 使用所有數據(包括重復試次)進行的分析與排除試次后的分析結果呈現出相同的模式。數據分析的過程中, 主要關注前一試次一致性與當前試次一致性的交互作用, 或年齡組×前一試次一致性×當前試次一致性的交互作用。如果上述交互作用顯著, 接下來則比較一致試次之后(cC vs. cI)和不一致試次之后(iC vs. iI)的一致性效應, 并比較cC與iC, cI和iI試次的反應, 來進一步明確一致性效應減少的來源。

對于任務2, 數據采集的過程中, 一名成人被試的數據丟失, 故排除這個被試的數據。任務2主要關注跨任務轉換類型, 對反應時和正確率進行年齡組 × 轉換類型(Stroop→Flanker vs. Flanker→ Stroop) × 前一試次一致性 × 當前試次一致性的重復測量方差分析。數據分析中, 反應時數據排除錯誤的反應以及試次之后的錯誤反應。此外, 為了直接比較成人和兒童在這兩項任務中的沖突適應效應的大小, 我們計算了反應時和準確率之間的差異分數。對于反應時數據, 差異分數的計算方式為:(RT– RT) – (RT– RT) (Nieuwenhuis et al., 2006); 正確率差異分數的計算為:(ACC– ACC) – (ACC– ACC), 差值越大, 表明認知適應能力越強。所有分析均以 < 0.05的值作為統計顯著性的標準, 以η作為效應量大小的指標。

3 結果

3.1 任務1結果

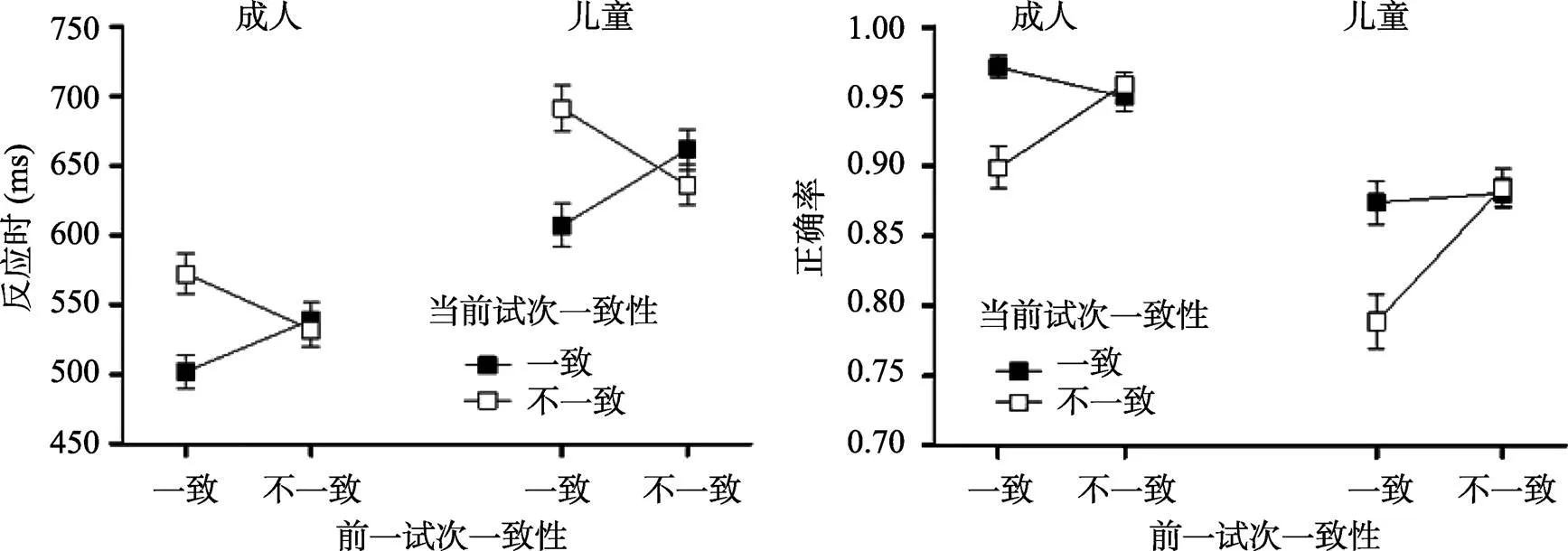

反應時和正確率的分析結果見圖2和表1。對反應時進行方差分析的結果表明, 年齡組的主效應顯著,(1, 65) = 35.28,< 0.001, η= 0.35, 成人的反應時顯著快于兒童; 當前試次一致性的主效應顯著,(1, 65) = 64.05,< 0.001, η= 0.50, 一致條件下的反應時顯著快于不一致條件; 前一試次一致性與當前試次一致性的交互作用顯著, 進一步事后分析發現, 一致試次之后(cC vs. cI)的一致性效應顯著,(1, 66) = 133.41,< 0.001, η= 0.67; 不一致試次之后(iC vs. iI)的一致性效應也顯著,(1, 66) = 10.19,= 0.002, η= 0.13, 但當前不一致試次的反應快于當前一致試次。cC試次的反應時顯著快于iC試次,(1, 66) = 62.41,< 0.001, η= 0.49; cI試次的反應時顯著慢于iI試次,(1, 66) = 64.83,< 0.001, η= 0.50, 表明存在一致性序列效應。然而, 成人(= 77.72 ms,= 61.88)與兒童(= 109.78,= 86.73)在CSEs的大小(差異分數) 上不存在顯著差異,(1, 65) = 3.02,= 0.09, η= 0.04。

對正確率進行分析發現, 年齡組的主效應顯著,(1, 65) = 34.44,< 0.001, η= 0.35, 成人的正確率顯著高于兒童; 前一試次一致性與當前試次一致性的交互作用顯著, 進一步分析發現, 一致試次之后(cC vs. cI)的一致性效應顯著,(1, 66) = 63.50,< 0.001, η= 0.49; 不一致試次之后(iC vs. iI)的一致性效應不顯著,(1, 66) = 0.55,= 0.46, η= 0.01, 同樣表明存在CSEs。iI試次的正確率顯著高于cI試次,(1, 66) = 52.66,< 0.001, η= 0.44; cC試次與iC試次的正確率不存在顯著差異,< 1。成人(0.080.09)與兒童(= 0.09,= 0.11)在CSEs的大小(差異分數)上不存在顯著差異,< 1。

3.2 任務2結果

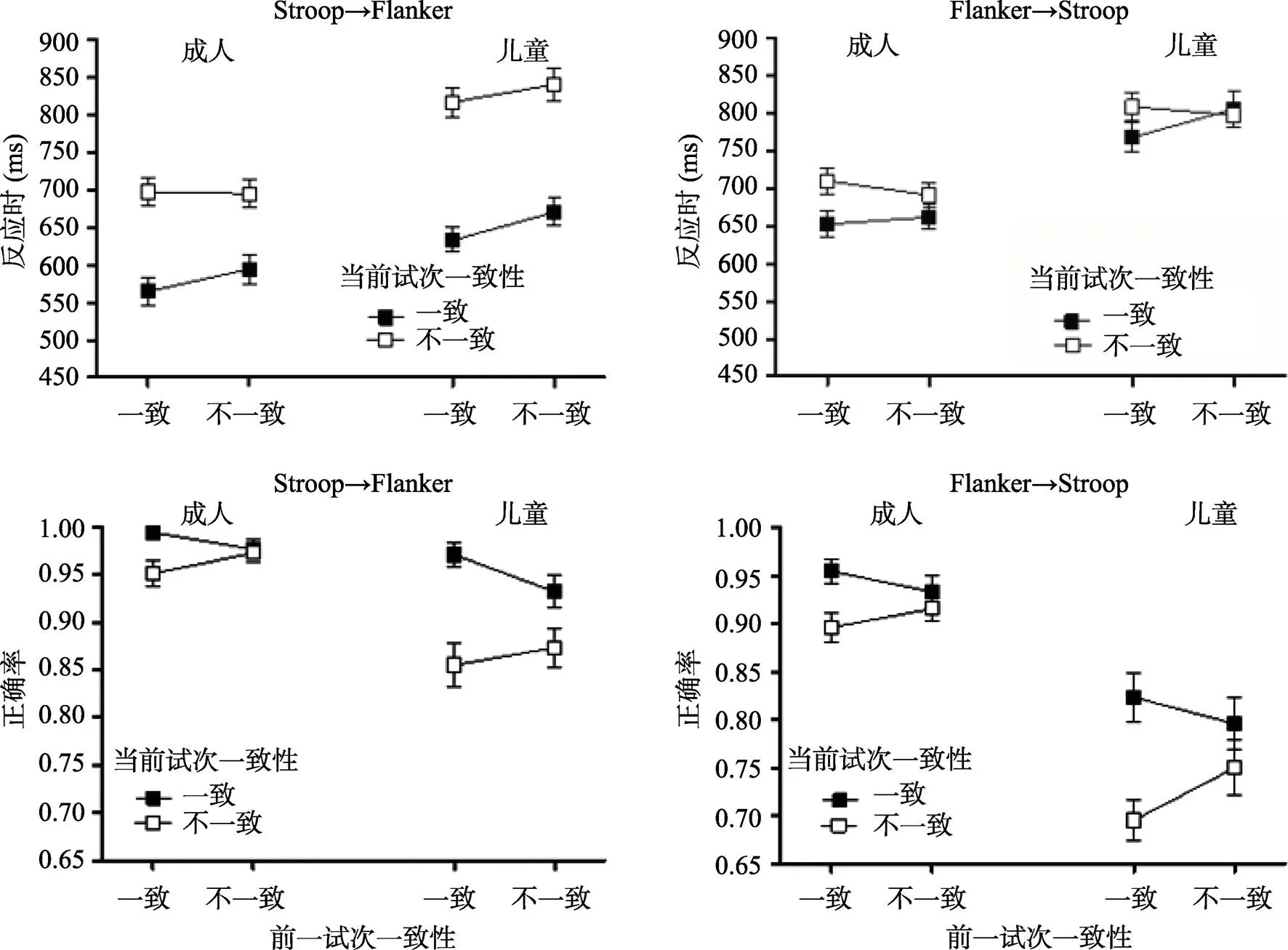

反應時和正確率的分析結果見圖3和表1。從圖3上方的圖中可以看出, 兒童和成人在反應時的數據上表現出相似的模式, 即與一致試次之后的一致性效應相比, 不一致試次之后的一致性效應略有下降, 這可能是由于cC試次的反應時快于iC所導致的。對反應時進行年齡組×任務轉換×前一試次一致性×當前試次一致性的方差分析, 發現主要關注的前一試次一致性×當前試次一致性的交互作用顯著, 一致試次之后(cC vs. cI)的一致性效應顯著,(1, 65) = 185.70,< 0.001, η= 0.74; 不一致試次之后(iC vs. iI)的一致性效應也顯著,(1, 65) = 123.70,< 0.001, η= 0.66。cC試次的反應時顯著快于iC試次,(1, 65) = 36.94,< 0.001, η= 0.36; 然而, iI試次與cI試次的反應時不存在顯著差異,< 1。CSEs的大小在不同年齡組以及不同轉換類型間不存在顯著差異, 其中, 在Stroop→Flanker轉換中, 成人(= 32.02 ms,= 52.47)與兒童(= 14.23 ms,= 75.21)差異不顯著,= 0.27; 在Flanker→ Stroop轉換中, 成人(= 28.34 ms,= 59.80)和兒童(= 48.86 ms,= 95.17)不存在顯著差異,= 0.30。其他主效應及其交互作用的具體結果見表1。

從圖3下方的圖中能夠看出, 兒童和成人在正確率的結果上同樣表現出相似的趨勢, 即與一致試次之后的一致性效應相比, 不一致試次之后的一致性效應有減少的趨勢。方差分析的結果發現, 任務轉換的主效應顯著,(1, 64) = 77.27,< 0.001, η= 0.55, Stroop→Flanker轉換的正確率顯著高于Flanker→Stroop 轉換, 表明個體對Flanker刺激的反應正確率要高于Stroop刺激。前一試次一致性與當前試次一致性的交互作用顯著, 簡單效應分析的結果表明, 一致試次之后(cC vs. cI)的一致性效應顯著, F(1, 65) = 57.09, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.47; 不一致試次之后(iC vs. iI)的一致性效應也顯著, F(1, 65) = 8.97, p = 0.004, ηp2 = 0.12。cC試次的正確率顯著高于iC試次, F(1, 65) = 9.76, p = 0.003, ηp2 = 0.13; iI試次的正確率顯著高于cI試次, F(1, 65) = 6.04, p = 0.02, ηp2 = 0.09。CSEs的大小在不同年齡組以及不同轉換類型間不存在顯著差異, 其中, 在Stroop→ Flanker轉換中, 成人(M = 0.04, SD = 0.07)與兒童(M = 0.06, SD = 0.18)差異不顯著, p = 0.61; 在Flanker→Stroop轉換中, 成人(M = 0.04, SD = 0.14)和兒童(M = 0.08, SD = 0.21)不存在顯著差異, p = 0.35。

圖2 成人和兒童在前一試次(一致vs.不一致)和當前試次(一致vs.不一致)的平均反應時和標準誤(左); 平均正確率和標準誤(右)

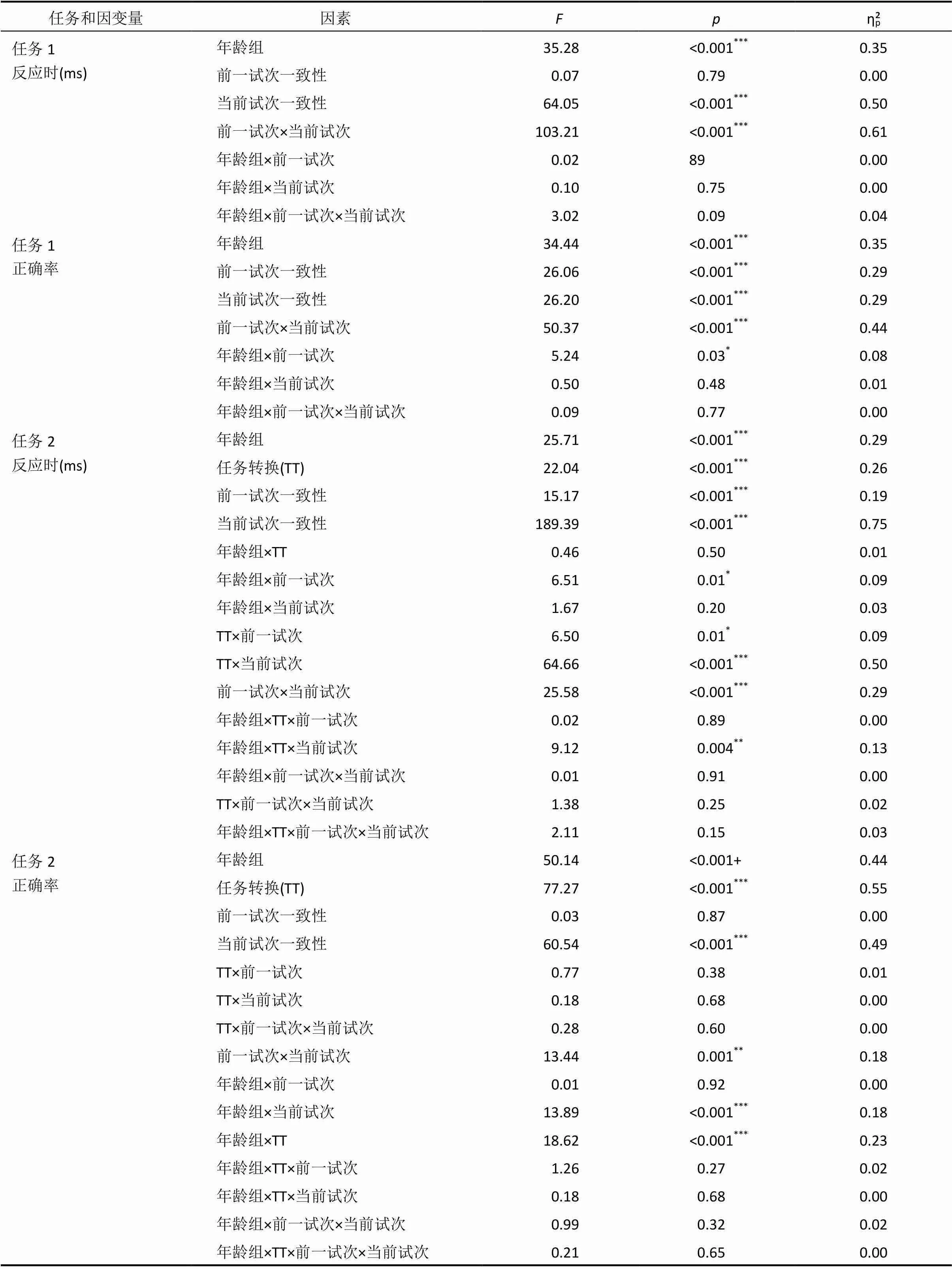

表1 任務1和任務2的統計分析結果

注:前一試次 = 前一試次一致性; 當前試次 = 當前試次一致性; 任務1中值對應的自由度為(1, 65), 任務2為(1, 64); *< 0.05, **< 0.01, ***< 0.001

圖3 Stroop→Flanker轉換中, 不同年齡組在前一試次(一致vs.不一致)和當前試次(一致vs.不一致)的平均反應時和標準誤(左上); 平均正確率和標準誤(左下); Flanker→Stroop轉換中, 不同年齡組在前一試次(一致vs.不一致)和當前試次(一致vs.不一致)的平均反應時和標準誤(右上); 平均正確率和標準誤(右下)

4 討論

在任務1(Stroop任務)中, 兩個年齡組表現出相似的行為模式及相似的CSEs差異分數大小, 不一致試次之后的一致性效應顯著小于一致試次之后的一致性效應。對于反應時數據, 一致性效應的減少, 是由于與不一致試次之后的一致試次(iC試次)相比, 一致試次之后的一致試次(cC試次)能夠誘發更快的反應, 同樣, 與一致試次之后的不一致試次(cI試次)相比, 不一致試次之后的不一致試次(iI試次)能夠誘發更快的反應。對于正確率的分析, 一致性效應的減少是由于兩個年齡組在iI試次上的正確率顯著高于cI試次。在任務2 (Stroop和Flanker刺激混合任務)中, 兩個年齡組在Stroop→ Flanker和Flanker→Stroop中同樣表現出了相似的CSEs行為模式及差異分數量。具體來說, 對于反應時數據的分析表明, 所有被試在cC試次上的反應時顯著快于iC試次, 對于正確率數據的分析卻發現, cC試次的正確率顯著高于iC試次, iI試次的正確率顯著高于cI試次。

任務1的結果與之前Larson等人(2012)的研究結果一致, Larson等人(2012)的研究中采用的任務為三色Stroop任務。本研究雖然在整體的反應時和正確率分析中發現了顯著的年齡差異, 但在兩個任務中, 兒童與成人均表現出了顯著的一致性序列效應。此外, 我們將所有涉及反應重復的試次排除在分析之外, 從而排除了特征整合或特征啟動效應的影響, 即排除了特征整合和特征啟動對CSEs的解釋(Hommel, Proctor, & Vu, 2004; Nieuwenhuis et al., 2006)。因此, 本研究中所觀察到的CSEs反映了較高級的認知適應過程, 而不是由于反應重復所引起的較低水平的加工過程。

通過實驗設計的方式, 跨任務轉換的任務2排除了簡單特征啟動的影響。在這種情況下, 兒童和成年人再次表現出類似的CSEs, 盡管與任務1相比, 兩組被試在任務2中的平均CSEs差異分數相對較小。這表明, 盡管參與沖突適應的大腦結構存在潛在的年齡差異, 但實驗結果仍提供了兒童認知控制適應的證據, 且這種適應性是跨任務的。因此, 兩個任務通過不同的方式, 排除了刺激特征的完全重復, 從而否定了基于特征整合或特征啟動的解釋。本研究結果在很大程度上支持了沖突監測理論,基于沖突監測理論的解釋, 與cI試次相比, 被試在iI試次中的反應時顯著較快且正確率較高, 這可能由于當被試遇到沖突信息時, 會持續對沖突信息進行監測, 調整自己的注意資源, 從而有利于下一沖突試次的適應。此外, 在考察一致性序列的任務中, 不可避免的會出現兩個連續的一致試次或不一致試次, 因此無法排除基于重復?預期的理論解釋。神經生理學的研究表明, 基于沖突監測理論的適應過程與基于重復?預期理論的適應過程之間存在著神經重疊(Duthoo et al., 2014b)。因此, 在適應沖突的過程中, 個體對同一類型試次的預期與自上而下的認知控制可能共同起著作用, 幫助個體有效的適應沖突環境。

對任務2反應時數據的分析表明, 前一試次一致性與當前試次一致性的交互作用不受轉換類型(Stroop→Flanker vs. Flanker→Stroop)的影響。然而, 從圖3(上方)中可以觀察到, 兩種轉換類型是存在差異的。具體來說, 對于Stroop→Flanker轉換, CSEs僅僅是由于cC試次的反應時顯著短于iC試次, 因此可能反映了注意范圍的擴大。相反, 對于Flanker→Stroop轉換, CSEs既由于cC試次誘發的反應時顯著短于iC試次(注意范圍的擴大), 同時又是由于iI試次的反應時顯著短于cI試次(注意的鎖定或集中)引起的。本研究結果與Freitas等人(2007)實驗2的結果一致, Freitas等人(2007)的研究以大學生為被試, 要求被試口頭匯報字體的顏色和箭頭的方向, 以考察跨任務的CSEs。因此, 與Stroop→ Flanker轉換相比, Flanker→Stroop轉換中CSEs的模式更加清晰。

總之, 本研究通過操控實驗設計和事后分析, 排除了低水平重復效應的影響, 保證了更為純凈的CSEs。在單任務和雙任務條件下, 均發現9~10兒童和成人表現出顯著的CSEs, 這一結果為該年齡階段兒童認知控制適應能力的發展提供了行為證據。本研究存在的第一個不足之處是, 實驗中采用了固定的任務順序。在實驗中, 所有被試均是首先完成任務1, 之后完成任務2, 這樣的安排是由于我們想要預先確定兒童的CSEs (Larson et al., 2012), 但這樣可能會導致在任務2中存在一定的練習效應。其次, 之前有研究對10~12歲兒童的反應抑制及干擾控制能力進行了訓練(Zhao, Chen, & Maes, 2018; Zhao & Jia, 2018), 發現與成人相比, 兒童抑制控制能力的可塑性較大。因此, 未來的研究可以考慮對兒童的沖突適應能力進行訓練, 以提高兒童處理沖突信息和靈活適應變化環境的能力。最后, 雖然9~10兒童大腦區域(如ACC和PFC)的發展相對不成熟, 但在行為結果上, 幾乎達到了成人的水平, 這為今后神經生理學的研究提供了證據和支持。Larson等人(2012)利用腦電技術的研究發現, 兒童與成人在沖突適應的過程中, 表現出相似的SP波幅(與沖突解決相關的成分)變化。Waxer和Morton (2011)的研究中, 利用腦電的溯源分析發現, 與cI試次相比, 成人和青少年在iI試次上ACC的活動降低, 然而并未在兒童身上發現這樣的模式。Wilk和Morton (2012)的研究中, 利用功能性磁共振成像技術, 考察9歲至32歲個體沖突適應中大腦活動的變化, 結果發現, 盡管各年齡組的行為表現相似, 但年齡較大的被試在前扣帶回、前腦島、外側前額葉和頂內溝皮層的激活程度更強。因此, 未來的研究應利用多種不同的技術, 深入考察9~10兒童沖突適應過程中是否涉及更廣泛的腦區, 并進一步明確CSEs本質及其年齡差異。

5 結論

本研究選取9~10歲的兒童和成人為被試, 采用單任務的色?詞Stroop任務及Stroop刺激和Flanker刺激的混合任務, 通過控制重復啟動效應的影響, 發現9~10歲的兒童在兩個任務中表現出與成人類似的一致性序列效應。表明沖突適應過程涉及更高級的加工過程, 且9~10歲兒童已經具備了一般化的沖突適應能力。

Adleman, N. E., Menon, V., Blasey, C. M., White, C. D., Warsofsky, I. S., Glover, G. H., & Reiss, A. L. (2002). A Developmental fMRI Study of the Stroop Color-Word Task.(1), 61–75.

Ambrosi, S., Lemaire, P., & Blaye, A. (2016). Do young children modulate their cognitive control? Sequential congruency effects across three conflict tasks in 5-to-6 year olds.,(2), 117?126.

Benikos, N., Johnstone, S. J., & Roodenrys, S. J. (2013). Varying task difficulty in the Go/Nogo task: The effects of inhibitory control, arousal, and perceived effort on ERP components.(3), 262–272.

Botvinick, M. M., Braver, T. S., Barch, D. M., Carter, C. S., & Cohen, J. D. (2001). Conflict monitoring and cognitive control.,(3), 624?652.

Braem, S., Abrahamse, E. L., Duthoo, W., & Notebaert, W. (2014). What determines the specificity of conflict adaptation? A review, critical analysis and proposed synthesis.,, 1134.

Brocki, K. C., & Bohlin, G. (2004). Executive functions in children aged 6 to 13: A dimensional and developmental study.(2), 571–593.

Cao, J., Wang, S. H., Ren, Y. L., Zhang, Y. L., Cai, J., Tu, W. J., … Xia, Y. (2013). Interference control in 6-11 year-old children with and without ADHD: Behavioral and ERP study.(5), 342–349.

Cragg, L. (2016). The development of stimulus and response interference control in midchildhood.,(2), 242?252.

Diamond, A. (2013). Executive functions.,(1), 135?168.

Duthoo, W., Abrahamse, E. L., Braem, S., Boehler, C. N., & Notebaert, W. (2014b). The heterogeneous world of congruency sequence effects: An update.,, 1001.

Egner, T., & Hirsch, J. (2005). The neural correlates and functional integration of cognitive control in a Stroop task.,(2), 539?547.

Erb, C. D., Moher, J., Song, J.-H., & Sobel, D. M. (2018). Reach tracking reveals dissociable processes underlying inhibitory control in 5- to 10-year-olds and adults.,:e12523.

Eriksen, B. A., & Eriksen, C. W. (1974). Effects of noise letters upon the identification of a target letter in a nonsearch task.,(1), 143?149.

Freitas, A. L., Bahar, M., Yang, S., & Banai, R. (2007). Contextual adjustments in cognitive control across tasks.,(12), 1040?1043.

Funes, M. J., Lupiá?ez, J., & Humphreys, G. (2010). Analyzing the generality of conflict adaptation effects.(1), 147?161.

Goldfarb, L., Aisenberg, D., & Henik, A. (2011). Think the thought, walk the walk - Social priming reduces the Stroop effect.(2), 193–200.

Gratton, G., Coles, M. G. H., & Donchin, E. (1992). Optimizing the use of information: strategic control of activation of responses.,(4), 480?506.

Hommel, B., Proctor, R. W., & Vu, K-P. (2004). A feature-integration account of sequential effects in the Simon task.,(1), 1?17.

Iani, C., Stella, G., & Rubichi, S. (2014). Response inhibition and adaptations to response conflict in 6- to 8-year-old children: Evidence from the Simon effect.,(4), 1234?1241.

Jiménez, L., & Méndez, A. (2013). It is not what you expect: dissociating conflict adaptation from expectancies in a stroop task.(1), 271?284.

Kerns, J. G. (2006). Anterior cingulate and prefrontal cortex activity in an fMRI study of trial-to-trial adjustments on the simon task.(1), 399?405.

Kray, J., Karbach, J., & Blaye, A. (2012). The influence of stimulus-set size on developmental changes in cognitive control and conflict adaptation.(2), 119–128.

Lamers, M. J. M., & Roelofs, A. (2011). Attentional control adjustments in Eriksen and Stroop task performance can be independent of response conflict.,(6), 1056?1081.

Larson, M. J., Clawson, A., Clayson, P. E., & South, M. (2012). Cognitive control and conflict adaptation similarities in children and adults.,(4), 343?357.

Larson, M. J., Kaufman, D. A. S., & Perlstein, W. M. (2009). Neural time course of conflict adaptation effects on the stroop task.(3), 663?670.

Luna, B., Garver, K. E., Urban, T. A., Lazar, N. A., & Sweeney, J. A. (2004). Maturation of cognitive processes from late childhood to adulthood.,(5), 1357?1372.

Luna, B., & Sweeney, J. A. (2004). The emergence of collaborative brain function: fMRI studies of the development of response inhibition.(1), 296?309.

Lustig, C., Hasher, L., & Tonev, S. T. (2006). Distraction as a determinant of processing speed.(4), 619–625.

MacLeod, C. M. (1991). Half a century of research on the Stroop effect: An integrative review.,(2), 163?203.

Mayr, U., Awh, E., & Laurey, P. (2003). Conflict adaptation effects in the absence of executive control.,, 450?452.

Miyake, A., Friedman, N. P., Emerson, M. J., Witzki, A. H., Howerter, A., & Wager, T. D. (2000). The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “frontal lobe” tasks: A latent variable analysis.(1)49–100.

Nieuwenhuis, S., Stins, J. F., Posthuma, D., Polderman, T. J. C., Boomsma, D. I., & de Geus, E. J. (2006). Accounting for sequential trial effects in the flanker task: Conflict adaptation or associative priming?,(6), 1260?1272.

Rueda, M. R., Fan, J., McCandliss, B. D., Halparin, J. D., Gruber, D. B., Lercari, L. P., & Posner, M. I. (2004). Development of attentional networks in childhood.,(8), 1029?1040.

Stins, J. F., Polderman, J. C. T., Boomsma, D. I., & de Geus, E. J. C. (2007). Conditional accuracy in response interference tasks: evidence from the Eriksen flanker task and the spatial conflict task.,(3), 409?417.

Titz, C., & Karbach, J. (2014). Working memory and executive functions: Effects of training on academic achievement.(6), 852–868.

Waxer, M., & Morton, J. B. (2011). The development of future-oriented control: An electrophysiological investigation.(3), 1648–1654.

Wilk, H. A., Ezekiel, F., & Morton, J. B. (2012). Brain regions associated with moment-to-moment adjustments in control and stable task-set maintenance.,(2), 1960?1967.

Wilk, H. A., & Morton, J. B. (2012). Developmental changes in patterns of brain activity associated with moment-to- moment adjustments in control.,(1), 475?484.

Zhao, X., Chen, L., & Maes, J. H. R. (2018). Training and transfer effects of response inhibition training in children and adults.,, e12511.

Zhao, X., & Jia, L. (2018). Training and transfer effects of interference control training in children and young adults.,

Congruency sequence effects in 9~10-year-old children and young adults

ZHAO Xin; JIA Lina; ZHOU Aibao

(Key Laboratory of Behavioral and Mental Health of Gansu Province;School of Psychology, Northwest Normal University, Lanzhou 730070, China) (Academy of Psychology and Behavior, Tianjin Normal University, Tianjin 300074, China)

Sequential congruency effects (CSEs) or conflict adaptation effects refer to the ability to flexibly and rapidly adapt interference control. The Gratton effect, as demonstrated using a standard Stroop or flanker task, can be explained in at least three ways. The first explanation is the conflict-monitoring account. A second theory is the repetition-expectancy account. A third explanation rests on the notion of low-level repetition effects and has been incorporated in the feature-integration or feature-priming account. Concerning age differences in CSEs, the great majority of studies examined adult populations. The relatively few studies that (also) examined children and adolescents, using one of the standard interference control tasks. Previous studies examining age differences in cognitive control adaptations, as reflected in congruency sequence effects (CSEs) in tasks inducing stimulus or response conflict, did not consistently control for priming confounds. Hence, answering the question whether or not children have an equal ability and pattern of cognitive control adaptations, relative to adults, still requires more research.

The participants were 33 adults with a mean age of 20.6 years and 34 children with a mean age of 9.5 years. The experiment consists of two tasks: Task 1 is a Stroop task; Task 2 consisted of a mix of trials from the Stroop and flanker tasks. The stimuli used for the Stroop task (Task 1) consisted of the Hanzi representing the word “RED” printed in red (congruent trial) or green (incongruent trial), and the Hanzi representing the word “GREEN”, also printed in red (incongruent trial) or green (congruent trial). These stimuli were also used in Task 2, which also incorporated a flanker task. The stimuli of the flanker task were five arrows that all pointed to the right or left (congruent trials), or with the middle arrow pointing in one direction and the surrounding arrows in the other (incongruent trials). The experiment was performed on two consecutive days. On the first day, participants performed the Stroop task (Task 1), the next day participants performed the Task 2. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to analyze the RTs and accuracy in the two tasks.

For Task 1, of primary interest, the Trial n-1 congruency × Trial n congruency interaction was significant. Follow-up analyses revealed that the congruency effect was significant after congruent trials (cC vs. cI trials). The congruency effect was also significant after incongruent trials (iC vs. iI trials). Responding on cC trials was faster than on iC trials and responding on cI trials was slower than on iI trials, reflecting a clear CSEs. The two groups did not differ in the size of the conflict adaptation effect. The accuracy data, also suggest a clear reduction of the congruency effect in both age groups, which seemed to be mainly caused by more accurate responding on iI relative to cI trials. For Task 2, the Trial n-1 congruency × Trial n congruency interaction revealed that, although the congruency effect was significant both after congruent (cC vs. cI), and incongruent trials (iC vs. iI), cC trial pairs were associated with faster responses compared to iC trial pairs. However, RTs on iI trials did not differ from those on cI trials. There was no difference between the groups in mean CSE magnitude for both the Stroop→Flanker and Flanker→Stroop transition trials. The accuracy data suggest a similar pattern.

The strong resemblance between CSEs observed for 9~10-year-old children and adult participants under both single- and two-task conditions adds to the behavioral evidence of cognitive control adaptation capacities in children of this age, which seem to reach adult-like levels despite a relative immaturity of brain areas that subserve those capacities in adults. Hence, the observed CSE reflected higher-order, cognitive adaptation rather than the lower-level effects potentially induced by response repetition.

cognitive adaptation; congruency sequence effect; colour-word Stroop task; Flanker task

2019-02-12

* 國家自然科學基金(31560283)資助。

趙鑫和賈麗娜為共同第一作者

B842; B844

周愛保, E-mail: zhouab@nwnu.edu.cn