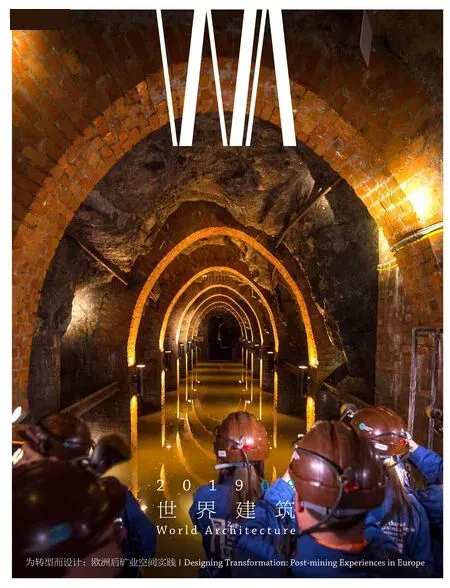

烏拉爾山的礦業遺產:自助設計、衰敗與荒地,烏拉爾聯邦管區,俄羅斯

娜杰日達·索洛寧娜,奧爾加·希皮齊娜,葉連娜·科丘霍娃,卡羅拉·S·諾伊格鮑爾 文/Text by Nadezhda Solonina, Olga Shipitsyna, Elena Kochukhova, Carola S. Neugebauer

尚晉 譯/Translated by SHANG Jin

烏拉爾山的礦業遺產體現出一種深刻的尺度和歷史。它可以上溯到17 世紀,那時沙皇彼得大帝下令開采礦床(磁鐵礦、銅礦、金礦等)[1],并在該地區施行城市化。到20 世紀初已開設了300 多座冶煉廠。蘇聯時期對這些工廠進行了現代化改造,并在該地區與新的單一型城市一同建立了新的工廠。1991 年,蘇聯的解體讓一切天翻地覆,舉步維艱:礦井和工廠或是縮減生產或是關停,失業率居高不下。有些企業實現了成功的私有化和現代化。于是就造成了今天空間和社會的兩極分化:一方面是欣欣向榮的地區首府葉卡捷琳堡1)(圖1、2),另一方面是大量人口萎縮、以單一行業為經濟基礎的小型工業城市。

在這一背景下,利益攸關的當地人滿懷熱情,將礦業遺產視為該地區向后工業社會轉型的一個巨大潛力。不過,到目前為止,這種熱情是不成體系的,缺乏政治保障和財政投入。現實中的“后礦業設計”包含了當地未能實現的愿景、自助行動和衰敗之美。下面的“后礦業設計”實例可以為此證明。

(1)衰敗與荒地之美正是烏拉爾山許多礦井、礦坑和礦渣堆的“設計”所在。盡管將原有廠房和煤礦的建筑單體通過再利用改造成博物館也是烏拉爾地區的常見做法(如塞維爾斯基博物館,圖3-5),整個礦業建筑群的再開發方式卻尚不明晰。相反,這些遺址表現出衰敗和荒地迷人的“設計”,吸引著追求極致的游客和專家(如杰格佳爾斯克礦井,圖6、7,或斯塔勞特金斯基冶煉廠,圖8、9)。它們只有最簡單的旅游基礎設施,比如觀景臺(如已關閉的戈羅布拉戈達茨基銅礦,圖10-12)。即使是國有的露天博物館,有時也不對游客開放,就像下塔吉爾2)——這個具有歷史價值的遺址將過去300 年的技術發展歷程匯于一地,卻缺少保護高爐的投資(圖13-15)。

(2)公眾參與加上企業家思維,是當地將后礦業遺址改造為教育、探險和文化場所的許多項目的基礎。它產生的是自助設計。

貝雷佐夫斯基市3)的“莎塔”博物館是大眾民俗設計(圖16-18)的一個例子。這家已經成功運行10 余年的博物館,起源于當地企業家瓦列里·洛巴諾夫的個人倡議:他希望讓城市悠久的采金歷史煥發生機。由于城市管理部門不支持他開設“互動博物館”的想法,洛巴諾夫租用了1960 年代的舊訓練礦,在排水清潔之后,按民俗風格復原了它。

1 烏拉爾山脈的許多城市都回到了利用水力的采礦業。因此大壩經常位于城市中心,葉卡捷琳堡也是如此/Many cities in the Ural Mountains go back to mining that used the power of water. The dam is thus very often in heart of the cities, also in Ekaterinburg

2 葉卡捷琳堡是一個蓬勃發展的后礦業城市/Ekaterinburg - a booming post-mining city(1.2圖片來源/Sources: Carola S.Neugebauer)

Mining heritage in the Ural Mountains displays an impressive scale and history. It dates back to the 17 century, when Tsar Peter the Great launched the exploitation of the ore deposits (magnetic iron ore,copper, gold, etc.)[1]and the region's urbanisation.Until the beginning of the 20 century, more than 300 metallurgical plants opened. In Soviet times,the plants were modernised and new factories found along with new mono-cities in the region. The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, triggered fundamental changes and hardship: Mines and factories reduced their production or closed down, resulting in high unemployment. Some enterprises underwent successful privatisation and modernisation. As a result, we witness today the polarisation of space and society: The booming regional capital of Ekaterinburg1)(Fig. 1, 2) on the one hand and many small industrial cities of shrinking population and mono-sectoral economic base, on the other.

Against this backdrop, enthusiastic local stakeholders consider the mining heritage as one important potential for the region's transition towards a post-industrial society. So far, however, this enthusiasm is splintered, lacking political commitment and financial investment. Actual "post-mining designs"range between unfulfilled local visions, do-it-yourself and the beauty of decay. The following examples of"post-mining designs" may illustrate that.

3-5 塞維爾斯基博物館/Seversky Museum(3-5圖片來源/Sources: Natalia Borozdina)

除了這種項目之外,當地的行動主義也帶來了后礦業建筑改造更多全面卻未能實現的愿景。目前的一個例子是瑟謝爾季4)城市中心項目。當地企業家揚·科然成立了“瑟謝爾季發展代理公司”,并邀請葉卡捷琳堡的建筑師為帶有舊水壩和冶煉廠的城市中心復興提出基本理念。后者被列為遺跡,卻完全廢棄,未來將改造成一個文化中心 (圖19-22)。如今,當地的行動和市長在為(地區或國家的)政府資金努力。

這幾個例子指出了烏拉爾礦業遺產的歷史價值與糟糕的保護利用狀況之間的尖銳矛盾。2010 年以來,每個秋季的烏拉爾當代藝術工業雙年展都試圖讓更廣泛的公眾意識到這一點。□

6.7 杰格佳爾斯克礦井——廢棄的行政大樓、車間和鍋爐房/Degtyarsky copper mine - The abandoned buildings of administration, workshops and boiler room(6.7攝影/Photos:Natalia Borozdina)

8.9 斯塔勞特金斯基冶煉廠/Staroutkinsky metallurgical plant(8.9攝影/Photos: Dmitry Khanin)

10 戈羅布拉戈達茨基銅礦燒結廠廢墟/The ruins of sinter plant, copper mine Goroblagodatsky

11 戈羅布拉戈達茨基銅礦采石場邊的觀景臺與紀念品/The observation platform on the side of quarry with memorial,copper mine Goroblagodatsky

12 戈羅布拉戈達茨基銅礦中央坑/The central pit of Goroblagodatsky mine(10-12攝影/Photos: Leonid Desyatov)

(1) The beauty of decay and wilderness is the"design" of many mines, pits and spoil heaps in the Ural Mountains. While the reuse of single buildings of former plants and collieries as museums is a common practice for in the Ural too (e.g. the Seversky Museum, Fig. 3-5), the redevelopment of whole mining complexes is not yet obvious. The sites rather display fascinating "designs" of decay and wilderness attracting extreme tourists and experts (e.g. the Degtyarsky mine, Fig. 6, 7; or the Staroutkinsky metallurgical plant, Fig. 8, 9). They rarely have minimal touristic infrastructures such as viewing platforms etc. (e.g. the closed copper mine Goroblagodatsky, Fig. 10-12). Even state-owned open-air museums are sometimes not accessible for visitors like in Nizhny Tagil2)- a historically valuable site showing the technological developments of the last 300 years in one place, but lacking investments to safeguard the blast furnace (Fig. 13-15).

(2) Civic engagement, combined with entrepreneurial thinking, is the base of several local projects to transform post-mining sites into places of education, adventure and culture. It results in Do-It-Yourself designs.

The museum "Shahta" in the city of Berezovsky3)is an example of popular folk design (Fig. 16-18).Working successfully for more than 10 years, this museum goes back to private initiative of the local entrepreneur Valery Lobanov, who wanted to bring to life the city's longstanding history of gold mining.Since the city administration did not support his idea to open an "interactive museum", Lobanov rented a former training mine of the 1960s, drained,cleaned and restored it in folklore style.

Apart from such projects, local activism also comes up with more comprehensive, yet unfulfilled visions for post-mining transformations. A current example is the project for the city centre of Sysert4).The local entrepreneur Yan Kozhan found the"Sysert Development Agency" and invited architects from Ekaterinburg to develop a first concept for the revitalisation of the city centre with the historic dam and a metallurgical plant. The latter is attempted as monument, but was totally abandoned and should become a cultural centre (Fig. 19-22). Now, the local initiative and mayor are striving for public (regional or national) funding.

These few examples point to the painful tension between the historic value of the Ural mining heritage and its deplorable state of preservation and use. Since 2010 in every autumn, the Ural Industrial Biennale of Contemporary Art seeks to sensitise a broader public for this.□

13-15 下塔吉爾/Nizhny Tagil(13-15圖片來源/Sources: Carola S. Neugebauer)

注釋/Notes

1)烏拉爾中部(斯維爾德洛夫斯克州)最大的城市,人口1,468,833。/Largest city in Central Ural (federal subject Sverdlovsk Oblast), 1,468,833 inhabitants.

2)烏拉爾中部(斯維爾德洛夫斯克州)第二大城市,人口353,950。/Second largest city in Central Ural (federal subject Sverdlovsk Oblast), 353,950 inhabitants.

3)葉卡捷琳堡旁的城市,人口57,192。/A city of 57,192 inhabitants close to Ekaterinburg.

4)葉卡捷琳堡旁的城市,人口20,962。/A city of 20,962 inhabitants next to Ekaterinburg.

16 “莎塔”博物館的窄軌鐵路和礦石運輸小車/Narrow-gauge railway and trolley for ore transportation in the "Shahta"

17 新博物館博覽會:參觀者可以與展品互動/New museum exposition: visitors can interact with objects

18 新博物館博覽會:俄羅斯帝國使用監獄勞力提取黃金。該圖說明了這種情況/New museum exposition: In the Russian empire for the extraction of gold used labor prisoners.The exposition and the figure here illustrates this situation(16-18圖片來源/Sources: the mine Museum)

19 振興瑟謝爾季市中心的設計理念,以大壩和大壩左側的工廠這些采礦遺產為標志/Design concept for the revitalisation of the Sysert city centre, marked by the legacies of mining - the dam and the plant on the left of the dam(圖片來源/Sources:Architectural group U.R.A.L. Render provided by Evgeniy Volkov)

評論

章明:一個簡單的設計評論并不能涵蓋烏拉爾山的礦業遺產,其呈現出了工業遺產或者說既有工業區在后工業時代面臨迭代更新時普遍存在的問題。在缺乏政策支持和持續、穩定資金來源的情況下,建議遵循荒地之美,向著“遺跡花園”的方向發展。可以選取一個特殊點進行更新改造,作為整個區域的接待中心和展陳介紹,和“荒地”形成對比。同時,在改造過程中應保證建筑與環境的安全性。

龍灝:想象一下,如果身處文中那些衰敗、蒼涼、悠遠以及尺度驚人的工業遺跡中間,會有怎樣的震驚與感嘆?悠久的采礦歷史和蘇聯傳統工業可以帶來的特殊美學體驗顯然是這些遺址未來發展的巨大機會。然而遺憾的是,俄羅斯當代的經濟現狀使得僅僅依靠個人的努力所實現的低水平利用,顯然尚不足以體現這些遺址在后工業時代的文化潛力,現有的“文化中心”開發意向也并未挖掘出這些遺址在評論者看來應具備的特殊美學價值。當然,名為“烏拉爾當代藝術工業雙年展”中的“工業”二字,不僅凸顯了這一地區的文化特色,也帶來了對這些遺址未來發展愿景的某種期待。

20 被廢棄的工廠建筑北立面/View on the abandoned plant building, north fa?ade(攝影/Photo: Evgeniy Volkov)

21 設計概念:新生的巴若夫山。工廠建筑北立面/Concept -the Bazhov hill after revitalization. View on the plant building,north fa?ade(圖片來源/Sources: Architectural group U.R.A.L. Render provided by Evgeniy Volkov)

22 設計概念:城市池塘和大壩景觀,右側是工廠西立面/Concept - view of the city pound and dam, on the right - the western fa?ade of the plant(圖片來源/Sources: Architectural group U.R.A.L. Render provided by Evgeniy Volkov)

Comments

ZHANG Ming: Mining Heritage in the Ural Mountains cannot be briefly judged by its design, for it reveals the general problems industrial heritage or existing industrial districts would face in the postindustrial era. Under the situation of lacking political support and continuous and stable financial sources,it is suggested that the mining heritage in the Ural Mountains should follow its beauty of decay and develops itself into a "garden of ruins". Meanwhile, it is also implied to choose one spot for regeneration,which works as the reception and display area for the entire region and forms strong contrast with the"deserted place". Besides, during the regeneration process, security of architecture and environment should be emphasized.

LONG Hao: Just imagine, standing at the foot of those desolate, pale and remote industrial monuments with their staggering scale as described in the text - what a shocking amazement! The aesthetic experiences that a long mining history and traditional Soviet industry can bring obviously introduce immense opportunities to these sites'development in the future. Yet regrettably,contemporary Russian economic conditions allow only low level use through personal efforts, which is apparently an understatement of these sites' cultural potentials in the post-industrial era. The current"Cultural Centre" development proposal has yet to explore the distinct aesthetic values that these sites deserve as the critic sees. Certainly the word"industrial" in the title "Ural Industrial Biennale of Contemporary Art" not only highlights the cultural identity of this area, but raises certain expectations about the vision of future developments for these places. (Translated by SHANG Jin)