Do PaCO2 and peripheral venous PCO2 become comparable when the peripheral venous oxygen saturation is above a certain critical value?

Lauren McGarey, Patrick Liddicoat, Matthew Gaines, Martyn Harvey, Grant Cave

1 Intensive Care Unit, Tamworth Base Hospital, Tamworth, New South Wales, Australia

2 Emergency Department, Tamworth Base Hospital, Tamworth, New South Wales, Australia 3 Waikato Hospital, Hamilton, New Zealand

Dear editor,

Peripheral venous blood gas (VBG) analysis is increasingly used as an alternative to arterial sampling in Emergency Departments throughout the world.[1]There are multiple advantages using peripheral venous samples for blood gas analysis - technical ease, reduced pain and fewer complications. The difference in sample site chosen for blood gas analysis between European and Australian centres has been notable for members of our author group, prompting discussion and review of the literature.

The consensus in the literature is that venous and arterial pH, bicarbonate and base excess are relatively interchangeable unless the patient is in a severely shocked state.[2]Peripheral venous partial pressure of CO2(PpvCO2) is reliable as a screen for arterial hypercapnia, considered non-comparable when PpvCO2is elevated above the normal physiological arterial range.

In the absence of significant anaerobic metabolism, the amount of CO2formed in any tissue is proportional to tissue oxygen delivery via the respiratory quotient. Oxygen delivery to any tissue bed can be measured as [haemoglobin] × (SaO2– tissue bed SvO2). This simple physiology has been used to create a validated method to mathematically “arterialise” peripheral venous blood – reverse modelling the process of oxygen extraction and CO2uptake, allowing reliable calculation of arterial CO2from a peripheral venous sample.[3]Despite the available evidence base, uptake of mathematical arterialisation of peripheral venous blood gas values remains incomplete.[4]

By the above physiologic rationale, the higher the peripheral venous oxygen saturation (SpvO2) the closer PpvCO2will be to PaCO2. We use this rationale, the evidence base for mathematical arterialisation and data from a laboratory experiment to generate the hypothesis that above a certain threshold SpvO2(approximately 75%) the difference between PaCO2and PpvCO2will be sufficiently small that it will fall within the limits of clinical agreement.

METHODS

Ethical approval for the experiment was granted by the Ruakura Animal Ethics Committee, Ruakura Agresearch, Hamilton, New Zealand. Interventions - anaesthesia, tracheostomy, ventilation, arterial and venous access were undertaken in rabbits as part of a toxicology protocol which has been previously reported.[5]At the completion of the toxicology protocol a convenience sample of contemporaneous arterial and venous blood gases was taken. Blood gases were analysed using an iSTAT Handheld point of care analyser (Abbott Point of Care in, Princeton, USA). SvO2and PvCO2, were measured from venous samples taken from the internal jugular vein, inferior vena cava and ear vein; PaCO2was measured from a central artery cannula. Presence of a relationship between SvO2and PvCO2-PaCO2was investigated with linear regression using the vassarstats website (www.vassarstats.net).

RESULTS

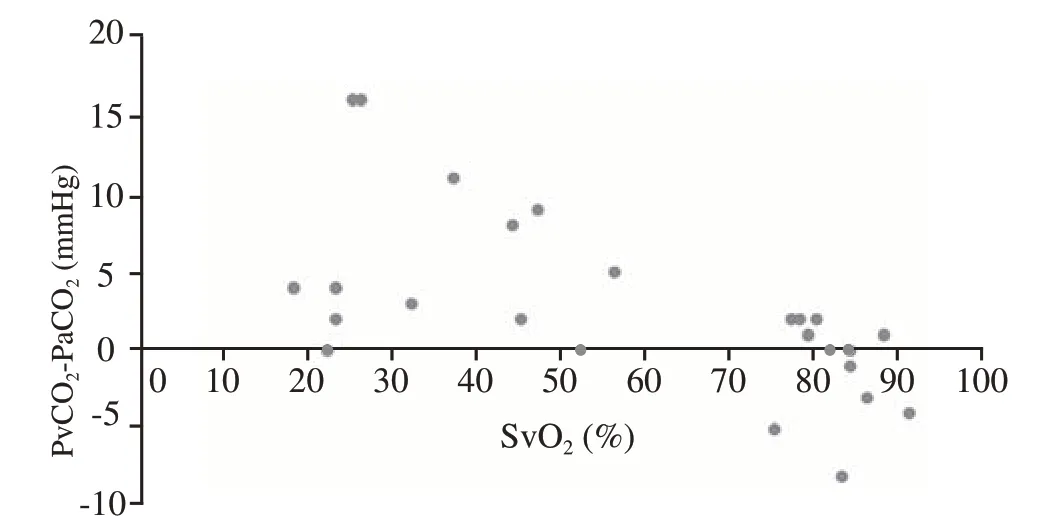

There were 23 paired venous and arterial gases for analysis. The difference between arterial and venous PCO2decreased with increasing SvO2. The slope of SvO2vs PvCO2-PaCO2was -0.14 mmHg/%saturation (99% confidence interval -0.25 to -0.03). This is displayed graphically in Figure 1.

DISCUSSION

Intuitively, the degree of difference in PCO2between arterial and venous blood is linked to the amount of oxygen extracted from arterial blood. This concept has been extended to a process of mathematical arterialisation of venous blood gas measures, which has a significant evidence base. One of the tenets of this method is that the difference in CO2carriage between arterial and venous blood is dependent on oxygen extraction – which will be necessarily greater with lower venous oxygen saturations and lesser with higher venous oxygen saturations. Our laboratory data are consistent with this argument.

The premise upon which this hypothesis rests is that all CO2entering venous blood is formed from aerobic metabolism. In the setting of ischaemia tissue bicarbonate buffers the acids formed from anaerobic metabolism, leading to anaerobic CO2formation. In the setting of vasodilatory shock with “wasted” perfusion the central venous O2saturation may remain high while tissue bicarbonate buffering in poorly perfused tissues increases central venous CO2. This forms the basis of the “CO2gap” concept where an increase arterial to central venous CO2partial pressure difference, even in the setting of high central venous oxygen saturations, is considered to be an indicator of inadequate overall perfusion.[6]This cause of increased arterial to venous CO2difference seems unlikely to relate to peripheral blood sampling in stable patients.

Figure 1. SvO2 vs. PvCO2-PaCO2.

Taking these arguments and laboratory findings together we hypothesise that, in the absence of shock or local ischaemia, there is a SpvO2above which PpvCO2provides a clinically acceptable estimation of PaCO2. Large databases of contemporaneous arterial and venous blood taken in clinical practice exist. It would be possible to pursue this hypothesis further using such data. If this hypothesis were proven it could both decrease use of PpvCO2when inappropriate, and potentially reduce unnecessary arterial sampling.

Funding:None.

Ethical approval:Ethical approval for the animal study was given by the Ruakura Animal Ethics Committee, Agresearch Ruakura, Hamilton, New Zealand.

Conf icts of interest:The authors have no confl icts of interest to report.

Contributors:GC conceived of the study; GC and MH undertook and analysed data from the animal study; LM led the writing of the fi rst draft of the manuscript with assistance from PL and MG. All authors contributed to subsequent drafts.

World journal of emergency medicine2020年3期

World journal of emergency medicine2020年3期

- World journal of emergency medicine的其它文章

- Information for Readers

- Myalgia may not be associated with severity of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)

- Syncope in a 3-year-old male: A case report

- A case of rhabdomyolysis with compartment syndrome in the right upper extremity

- A case of diffuse alveolar hemorrhage following synthetic cathinone inhalation

- Evaluation of gastric lavage eff ciency and utility using a rapid quantitative method in a swine paraquat poisoning model