Yak of All Trades

A New Year celebration on the plateau showcases modern Tibetan herding culture

我在西藏高原放牧牦牛,過藏歷新年,體驗變化中的藏族文化

Text and photography by MadsVesterager Nielsen

Additional Photographs from VCG

Illustration by Cai Tao

“Eat more,” Kelsang insists. He passes the metal bowl to me, filled to the brim with boiled pieces of meat the size of clenched fists. “Eat more. You must be hungry after such a long trip.” The meat tastes like beef, perhaps with the gaminess of lamb, but it has the distinct musky tone of yak.

My Tibetan hosts are sitting around the stove, fueled with yak dung and unceasingly radiating heat to all corners of the room. When the lid is lifted, just for a moment, the orange glow of the smoldering dung cakes reflect in the golden ornaments, prayer mills, and shrines that ordain the walls.

My hosts have been eagerly awaiting my arrival from Chengdu, the lowland capital of western China’s Sichuan province, to their small cottage high up on the Tibetan Plateau, some 3,500 meters above sea level. I have long wanted to explore Tibetan culture, and had traveled to this part of northern Sichuan to assist Kelsang’s family of yak herders during the Tibetan New Year celebrations, known as Losar. So far, I am not quite sure how—or if—I can help.

I can tell that the life of a herder is not an easy one, just by gazing at my hosts under the dim lights of the stove. Kelsang’s mother is dressed in traditional Tibetan garments, her long black hair braided and reaching down to her hips. She wears a silver ingot belt with a golden hook and a long orange coral necklace, both signs of a married Tibetan woman. Her face is kind and carries long deep wrinkles that attest to the 60-some harsh Tibetan winters that she has survived.

Next to her, Kelsang’s brother sits, wrapped in the red robes of the Tibetan clergy. His profile is small and his body appears to be bent beneath the robes. “My brother has scoliosis,” Kelsang says. Scoliosis, a curvature of the spine, is common here due to the altitude and meat-heavy diet. “He cannot work with the yak, so he became a monk instead.”

A table in the middle of the living room is covered with cans of Coca-Cola, Sprite, Chinese iced tea, as well as nuts, milk candies, and chocolates. A pyramid of about 20 , Tibetan steamed buns filled with yak fat and meat, rises from the table like a small shrine. A kettle on the stove steams with yak butter tea, whose aroma I caught hundreds of meters away as I arrived at the village.

It is all to show abundance during the Tibetan New Year, which falls around the same time when the rest of China observes Lunar New Year. “Eat more,” my host says and stretches his arm out over the table to show the wide selection of foods I may choose from. “Perhaps you will become a yak cowboy too!” He laughs heartily.

Greater Tibet, or what some refer to as “cultural Tibet,” extends far beyond the boundaries of the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) in present-day China. There are significant Tibetan populations and cultural bases in the provinces of Qinghai, Gansu, Sichuan and Yunnan, and inside the borders of India, Bhutan, and Nepal.

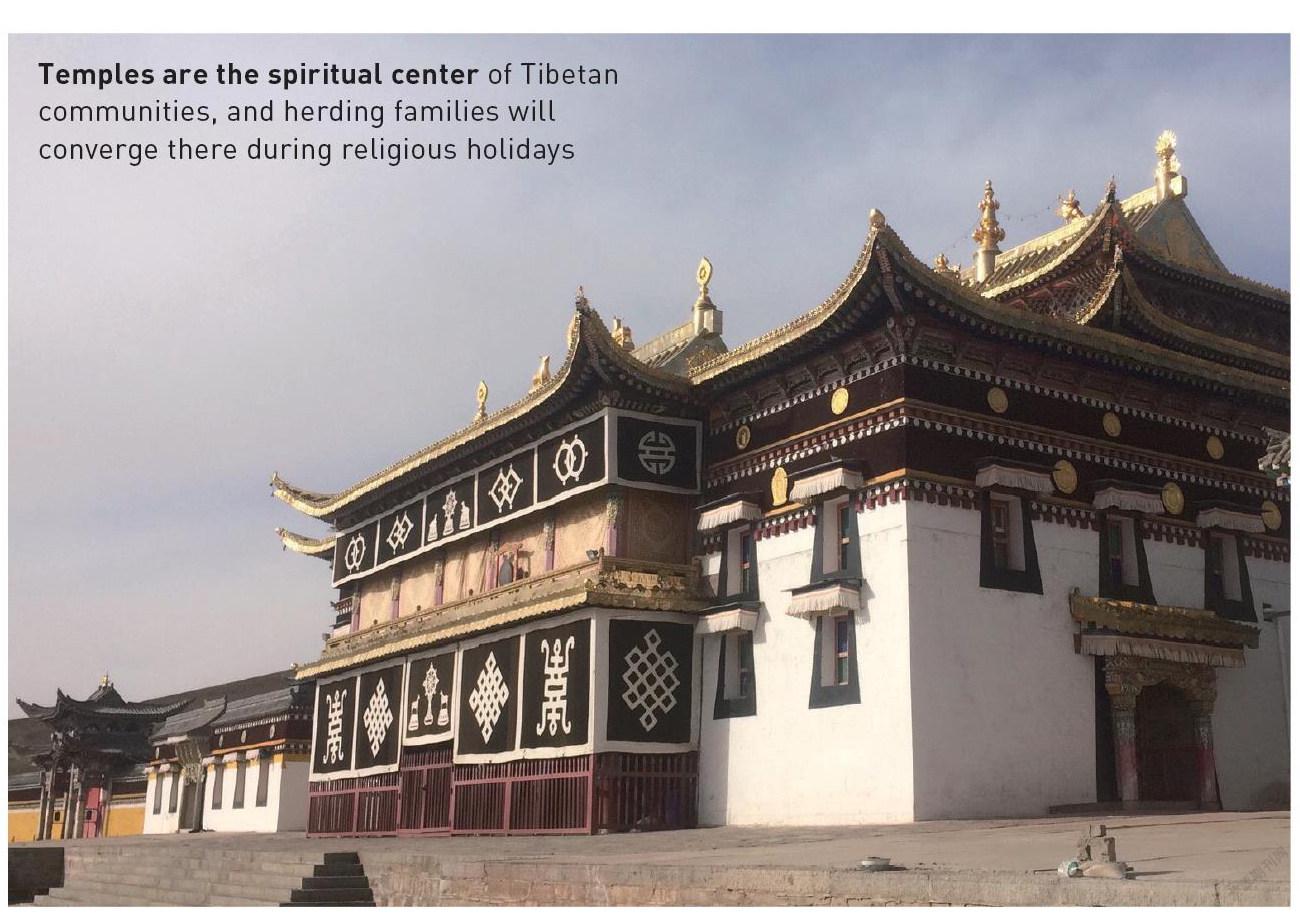

Kelsang’s family lives in the Ngawa, or Aba, region of northern Sichuan, just 100 kilometers from the Labrang Monastery of the Gelugpa sect, one of the most important religious sites in Tibetan Buddhism. Even though this mountainous grassland region covers one-sixth of Sichuan’s total landmass, its 900,000 inhabitants, over 50 percent of whom are Tibetan, only make up 1.2 percent of the province’s total population. South Ngawa is riddled with mountains and deep gorges, and encompasses the county of Wenchuan, the site of the catastrophic earthquake in 2008.

In the north, the region borders Gansu province and is covered by highland grasslands, reminiscent of the Mongolian steppe. The grasslands are famed for their horses and yaks, and horseback riding is a treasured skill of the yak herders. Every August, riders show off their skills at horse festivals throughout the highland steppes.

Because most crops can’t survive at such high altitude, yak has been the main source of sustenance for locals. In lowland Tibetan habitats, such as Yunnan and parts of western Sichuan, the barley, an important staple food for Tibetans, is cultivated.

Traditionally, the yak, known as in Tibetan and (牦牛) in Mandarin Chinese, has been the center of the highland economy. Herders like Kelsang’s family could trade meats, furs, bones, and horns for products like barley, metals, and jewelry.

Because the yak is so crucial to the life of Tibetan herders, it has taken on a mythological role that connects the practicalities of daily life with the spiritual world. Here, the wild yak is widely revered as the embodiment of the spiritual force of Tibet. Anthropologists often identify Tibetan herders as practicing distinct ”yak-culture,” much like the buffalo culture of the Indigenous peoples of the North American plains.

One often cited legend describes the friendship and sacred contract between the herder and the yak. The Tibetan herder may domesticate the yak and live off of it, but the herder is also obliged to release some yaks back into nature, symbolizing the willingness to acquiesce to the wild nature of the animal. According to folklore, the released yak would be able to tell other yaks how well it was treated by the herders.

In Tibetan legends and folksongs, this bond between humans and the animal is a recurrent theme. Like the Han Chinese Kitchen God, this legend creates a mythological incentive for the family to work hard and act morally—or the yak could tell the rest of the herd. There is also a Buddhist rationale for eating yak meat, according to Kelsang, as it is more filling than other animals: “If we take the life of one yak,” he says with all seriousness, “it’s better than killing many chickens or pigs.”

Nowadays, the Tibetan economy no longer sustains itself solely on yaks. There have been major changes to the herders’ way of life since the 1950s, when villages were organized into “work units,” and the 1960s, when their herds were collectivized.

In order to fit into the work-unit system, herders were required to keep fixed dwellings and limit their nomadic migration, which was traditionally required for the herds to find better pastures. After the economic reforms of the 1980s, some Tibetan families opened small businesses, and in the 2000s, the central government began promoting domestic tourism to the area.

As a result, families that used to own several yak herds and assist each other in nomadic activities have gradually branched out into other industries. The modern steppe economy includes temples, yak herding, law enforcement, tourism, and retail sales of local products. Kelsang’s family is trying to tick as many of these boxes as possible. Kelsang’s brother and an uncle are monks at the local monastery, while several cousins are still day-to-day herders out on the steppes. A few are semi-nomadic, returning in winter to stay with the herds and run businesses in the village.

A few distant cousins live in Chengdu and Lanzhou, where the family’s yak meat is distributed and resold. This allows one family to control as much of the value chain as possible, cutting out the middle brokers. Kelsang’s extended family has a herd of about 300 yaks, and he informs me that one healthy ox can be sold for about 5,000 yuan—meaning, technically, their family has a net worth of 1.5 million yuan.

The extended family resembles a tribe, in which members serve various functions in a concerted effort to support the greater family economy. In the family-tribe, Kelsang is the all-round fixer who takes care of the family’s newest investment: the construction of a hotel in the village, which by the time I arrive has not yet been completed. This great concrete skeleton with a neon sign, “Kelsang’s Yak Hotel,” is to be my home for the night.

Tourism is already firmly established in the Ngawa region. Just a couple of kilometers from the village is the famous Nine Bends of the Yellow River, which has become a major tourist attraction. It has a viewing platform, souvenir stands, and long stairs that crawl up and down the grassy hills. Tourists typically arrive there in tour groups by chartered buses. This is the business that Kelsang’s family hopes to get a slice of.

The “hotel” is all but a concrete shell, rising a full six floors up over the steppe landscape. Kelsang and his family resides on the ground floor in a back room. It is unheated and as frozen as the highland steppe itself, so I huddle up under several layers of blankets while feeling the frost settling on my eyelids.

The snow scatters and sporadically collects on the frozen grasslands, beneath the towering peaks in the distance. “How are you feeling today?” Kelsang asks the next morning with a smile. “No altitude sickness?” I had other things to worry about, such as keeping warm through the night, but the effects of the altitude was not one of them. Some Tibetans in the highlands used to think altitude sickness was caused by evil spirits brought from the lowlands, since only people from the lowlands suffered from it.

By mid-morning, the festival crowd has gathered in the middle of the village. Ten lamas sit in front of the stage, turning prayer mills in their hands and chanting. Beside them stand some 200 herders, all dressed in black and brown robes. Some of the young men wear headbands and sunglasses. There are dancers performing onstage, accompanied by bass-laden music so insistent it would have found itself right at home at an underground club in Berlin.

A musician graces the stage with the four-stringed , a Tibetan lute, and sings to a backing track. The track has a heavy folk feel with string arpeggios accentuated by his rusty Tibetan vocals that occasionally soars to mix with throat singing.

There are many yak “cowboys” here: suave-looking young men wearing knock-off Ray-Ban sunglasses that reflect the sunlight in orange-blue tints, like ski goggles. Unlike young people from other rural parts of China who become migrant workers, a significant portion of young people here on the steppe have remained in the village. They can take up one of the many branches of the family-tribe economy, benefiting from more diverse opportunities than their parents’ or grandparents’ generations.

But the job as a yak herder is more than a money-making endeavor. It also preserves the identity and continuity of the Tibetan herding traditions. There is a sense of pride with which the cowboys carry themselves. As the show progresses, many pull out smart phones from under their yak fur coats to take pictures of the Tibetan singer.

After the performance, Kelsang waves me over to help disassemble the stage, which I now realize is just made up of heavy cement blocks stacked together and covered by a red carpet. We pry the blocks free and lift them on to a waiting tractor in teams of two. I lift one by myself—“Easy, don’t hurt yourself!” Kelsang says. As the tractor chugs away, a couple of the Tibetan men smile and shake my hand. Some snap pictures of me with their smart phones or pull me in for a selfie.

“They are impressed with your help today,” Kelsang notes. “I think you are OK to help us with the yak.” I was not aware that this was a test, but I am exceedingly delighted to learn that I have passed. Soon I am in Kelsang’s white Suzuki Swift car, racing across the rugged grasslands with Kelsang behind the wheel and three other herders in the backseat.

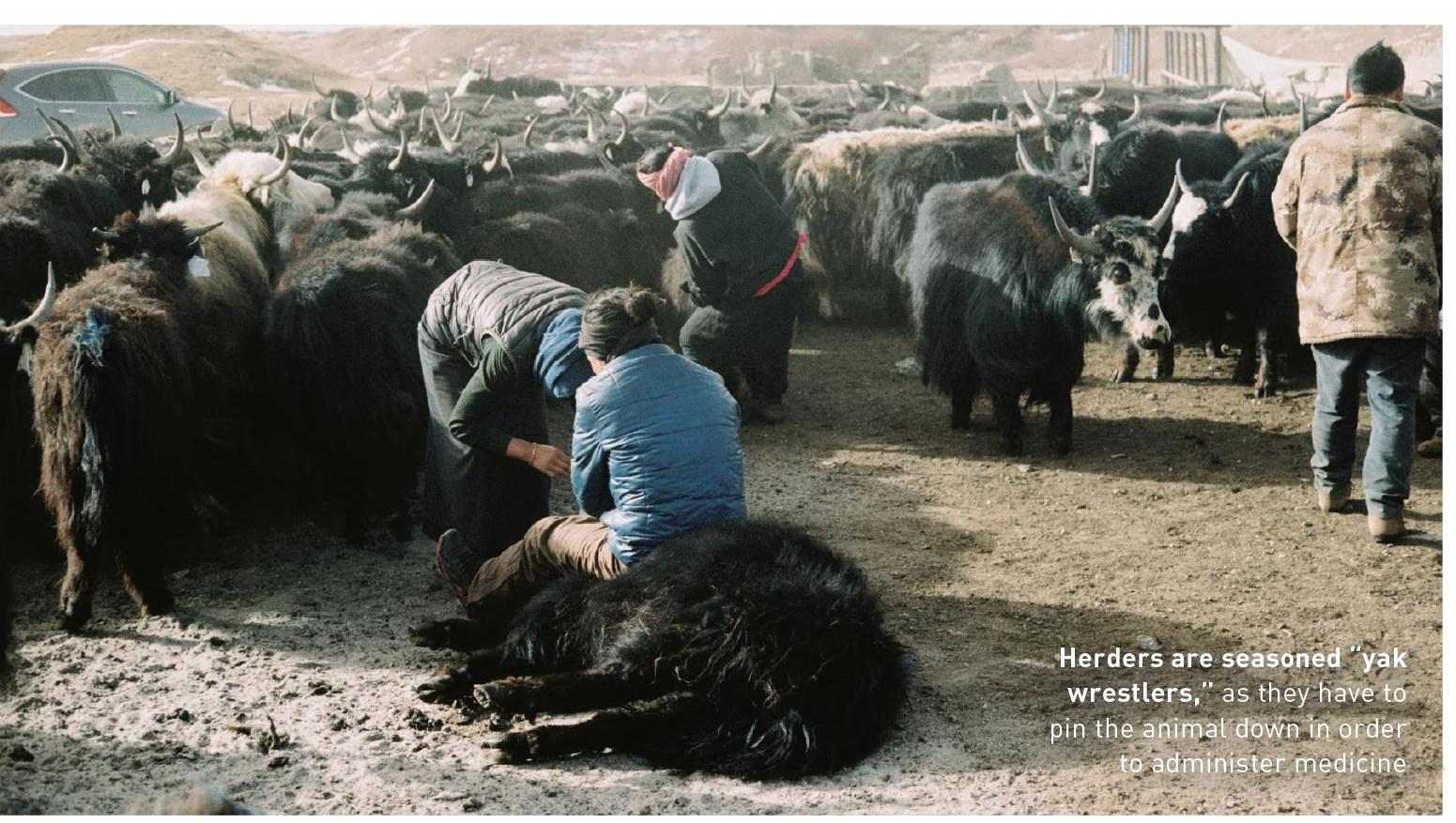

The yaks are already in the pen. During the New Year, the herders administer medicine for the herd.? “Otherwise, many of them would die,” Kelsang says. Temperatures in winter can reach minus-30 degrees Celsius at night, and hover around minus-15 in daytime.

Traditionally, herders would feed the yaks with salt to keep them strong in the harsh cold. The medicine that we are administering is for deworming their organs. “It is tough up here in the winter, even for a yak,” Kelsang concludes.

In order to give the medicine to the yak, I literally have to pin it down to the ground. “Grab the horns, and roll the yak around,” Kelsang instructs. “It will get confused and fall over.” He pauses. “Or it will fight you.” He laughs. “If the yak falls over, sit on its shoulder and brace your feet against the horns.”

Sounds easy enough—for a seasoned yak herder who has grown up wrestling 300-kilogram beasts on the Tibetan Plateau. This particular ox has hoofs the size of dinner plates and half-meter-long horns that can do some serious damage if you get stamped on or mauled. I have an early victory with a yak, successfully pinning it down. Kelsang and one of the other herders rush over to feed it medicine and water, and paint a blue marker on its back to indicate that it has been medicated.

“What about that one?” Kelsang points to one of the bigger yaks. As an outsider eager to prove myself, I jump at the yak without blinking. This time, it fights. I hang on tight to the horns of the great ox, but to no avail. I am dragged along on the side of the yak for about ten meters before I crash hard onto the frozen ground.

Kelsang cuts off a piece of a yak’s horn and throws it to me—“Here’s a little souvenir from your time in Tibet!” The bruises will be another souvenir, I think.

We ride out to get the last of the yaks down from the surrounding hills, and when we are done, we wash our faces and hands by a hose in the courtyard of one of the herders’ families. Some of the men even take off their jackets, exposing their naked upper bodies to the sub-zero temperatures. My People’s Liberation Army jacket catches a heavy dose of musk after my encounters with several yak. Many months later, it would still carry the same smell.

“Let me show you all the things we get from the yak,” Kelsang says with pride in his voice. In the skeletal structure of the hotel, he has assembled an improvised souvenir counter, filled with products all made from the yak: a hot pot soup base made with yak fat and Sichuan peppers, yak tallow soaps, yak skins and furs, and dried yak meat.

The hot pot base is a newfound success with Han Chinese tourists, Kelsang assures me. He has even been able to sell bones and organs to retailers in traditional Chinese medicine.

We head off to the nearby tea house to join for a meal and singing after the festival and the successful yak-deworming. “Eat more.” Kelsang commands with a smile. “Eat more. You did well today with the yaks.” On the table are more metal bowls with boiled yak meat. A knife lies on top, ready to cut off inch-thick cubes.

He strums a mandolin and leans into the violent crescendo of a Tibetan song. Then his demeanor changes.

“This one is about a white yak,” he says as his face lights up. After Kelsang’s song, the girls who are sitting on the floor sing one by one. “This one is about two lovers on the steppe.”

I take one more—just one more—while we slowly get tea drunk. The song passes from person to person in this dimly lit room in the Tibetan grasslands, and the next generation of herders chimes in their voices together with the family-tribe.

A man plays the dramyin at the Tibetan New Year festivities

Herders working with the yak herd owned by their extended family

Herders are seasoned “yak wrestlers,” as they have to pin the animal down in order to administer medicine

A herding family prepares their winter encampment far away on the highland steppe

Temples are the spiritual center of Tibetan communities, and herding families will converge there during religious holidays

漢語世界(The World of Chinese)2022年1期

漢語世界(The World of Chinese)2022年1期

- 漢語世界(The World of Chinese)的其它文章

- On the Character: 動

- No Excuses

- Rough Cut

- When China Goes on the Road

- A New Way of Seeing

- 學中文