建筑的絕對(duì)可持續(xù)性視角

安妮·貝姆,英格博格·豪

前文《何謂絕對(duì)可持續(xù)性》介紹了我們?cè)谒伎冀ㄔ炜沙掷m(xù)性時(shí)對(duì)其含義產(chǎn)生的新理解。在本文中,我們將討論相關(guān)策略對(duì)未來(lái)的建筑環(huán)境和我們的生活條件可能有哪些影響(圖1)。

1 再利用木圍護(hù)的細(xì)部 Detail of reused wood cladding

新的可持續(xù)實(shí)踐將如何影響我們思考、設(shè)計(jì)和建造建筑的方式?基于地球邊界的概念,絕對(duì)可持續(xù)性的審美和感官體驗(yàn)將是怎樣的?在建筑世界中,絕對(duì)可持續(xù)性看上去、聞起來(lái)和給人的感受將是怎樣的?

1 普遍問(wèn)題下的普適風(fēng)格

如果我們回顧過(guò)去70 年,建筑材料的使用在建筑歷史中不過(guò)是一個(gè)小小的插曲。在20 世紀(jì)之前,材料不僅選擇極為有限,而且往往只經(jīng)過(guò)極低程度的加工,建造方法也比今天簡(jiǎn)單得多。然而,當(dāng)我們回顧過(guò)去70 年的影響,以及高度技術(shù)化和能源密集型的建筑方法對(duì)我們的生活標(biāo)準(zhǔn)、全球發(fā)展以及地球的影響(現(xiàn)在狀況不佳)時(shí),其重要性不言而喻[1]。

討論建筑的絕對(duì)可持續(xù)性策略時(shí),需要著重思考“新”的資源密集型建造方法和我們當(dāng)代的建筑文化[2]。為了最終消除碳排放、廢物和建筑行業(yè)的污染效應(yīng),事情應(yīng)當(dāng)向好的方向轉(zhuǎn)變。

二戰(zhàn)后,工業(yè)化國(guó)家的現(xiàn)代建筑意味著擴(kuò)大化的中產(chǎn)階級(jí)的生活水平有所提高。中等收入家庭得以從市中心衛(wèi)生條件不佳的公寓搬出,那里有太多人住在擁擠的低標(biāo)準(zhǔn)建筑里[3]。取而代之的是,他們搬到了郊區(qū)新建的標(biāo)準(zhǔn)住宅區(qū)或獨(dú)棟平房中,那里有室內(nèi)管道、新鮮空氣、日光和充足的綠化[4]。

The previous article "What is absolute sustainability" introduces a new understanding of what we mean when we consider something built to be sustainable.In this article,we'll discuss what these strategies might mean for the future built environment and our living conditions (Fig.1).

How will new sustainable practices impact the way we think,design,and build architecture?What are the aesthetics and sensory experiences associated with absolute sustainability based on planetary boundaries? And how will absolute sustainability look,smell and feel in the world of architecture?

1 A Universal Style with Universal Problems

If we look back over the past 70 years,the use of materials for buildings is not much more than a minor parenthesis in the long history of architecture.Before the 20th century,the selection of materials was limited and often only minimally processed,and the construction methods were simpler than what we see today.However,when we look at the impact on our living standards,global development,and the (now poor) condition of our planet,the impact of these past 70 years and their highly technological and energy-intensive building methods cannot be overstated[1].

When discussing strategies for absolute sustainability in architecture,"novel" resource-intensive construction methods and our contemporary building culture need to be addressed[2].Ultimately,things need to change for the better to eliminate the negative consequences of carbon emissions,waste,and pollutive effects in the construction sector.

Modern architecture in industrialised countries in the period after WWII meant a rise in living standards for an expanding middle class.Families with middle incomes became able to move out of the unsanitary apartments in city centres,where too many people were living in overcrowded lowstandard buildings[3].

Instead,they moved into newly constructed uniform building blocks or bungalows in the suburbs,where they had access to indoor plumbing,fresh air,daylight and green surroundings[4].

Furthermore,due to mass production,new infrastructure,and the innovative use of materials such as reinforced concrete,steel and composites,development happened fast and at an affordable cost for the masses.In the 1960s and 1970s,new buildings and structures appeared at a considerable rate in the suburbs of large cities in industrialised countries and beyond.

On an even bigger scale,this period also marks the advent of megacities in Southeast Asia,the USA and South America,with the shift to market-driven socialism (e.g.in China) and special economic zones setting economic growth free.Concurrently with this enormous expansion of cities and infrastructure around the world,carbon emissions have also increased substantially[5].

2 From Growth to Reconsideration

Today,the aim is to improve our built environment to make it more sustainable,but to do that we cannot use market economy measures for success,such as growth in wealth or productivity.In order to advance the built environment within the planetary boundaries,we need to carefully consider all the materials,processes and solutions that go into every single structure we intend to build.The most sustainable structure is "the building we don't build," and the most sustainable materials are the materials we do not harvest,process,or use in construction.

Against the backdrop of the oil crisis of the 1970s,a broad understanding finally began to emerge in industrialised countries that they must share our planet's resources with the rest of the world.The planet's resources are everyone's resources.As with energy-intensive societies,all industrialised countries have a responsibility to reduce their carbon footprint and act within the safe operating space of the planetary boundaries.

Consequently,when we design and build today and in the future,we must apply "strategies of avoidance" to reduce our general consumption and exploitation of materials and energy resources.In addition,we must ask ourselves: Do we really need a new building? Can we use an existing one? Can we renovate an older building for new purposes? Can we transform buildings for multi-functional use or long-perspective purposes?

此外,由于大規(guī)模生產(chǎn)、新基礎(chǔ)設(shè)施和對(duì)鋼筋混凝土、鋼鐵和復(fù)合材料的創(chuàng)新使用,房產(chǎn)開(kāi)發(fā)迅速以可負(fù)擔(dān)的成本適應(yīng)了大眾需求。在1960 年代和1970 年代,工業(yè)化國(guó)家大城市的郊區(qū)迅速出現(xiàn)了許多新建筑。在更大的范圍上,這個(gè)時(shí)期,東南亞、美國(guó)和南美的超級(jí)城市的出現(xiàn),意味著市場(chǎng)驅(qū)動(dòng)的社會(huì)主義(例如中國(guó))和設(shè)立經(jīng)濟(jì)特區(qū)使經(jīng)濟(jì)得以快速增長(zhǎng)。然而,與全球城市與基礎(chǔ)設(shè)施的巨大擴(kuò)張同時(shí)出現(xiàn)的是碳排放大幅增加[5]。

2 從增長(zhǎng)到重新審視

當(dāng)前的目標(biāo)是改善我們的建成環(huán)境,使其更加可持續(xù),但為了做到這一點(diǎn),我們不能用市場(chǎng)經(jīng)濟(jì)衡量成功的標(biāo)準(zhǔn),比如財(cái)富增長(zhǎng)或生產(chǎn)力,來(lái)看待這一問(wèn)題。為了在地球邊界內(nèi)推動(dòng)建筑環(huán)境的改善,我們需要仔細(xì)考慮每一座計(jì)劃建造的建筑中涉及的所有材料、工藝和解決方案。最可持續(xù)的建筑是“我們不建造的建筑”,最可持續(xù)的材料是我們不采集、加工或用于建筑的材料。

在1970 年代的石油危機(jī)背景下,工業(yè)化國(guó)家終于開(kāi)始形成一個(gè)廣泛的認(rèn)識(shí):必須與世界其他地方分享我們地球的資源。地球資源是每個(gè)人的資源。作為能源密集型社會(huì),所有工業(yè)化國(guó)家都有責(zé)任減少碳足跡,并在地球邊界的安全運(yùn)營(yíng)空間內(nèi)行事。

因此,當(dāng)今天和未來(lái)進(jìn)行設(shè)計(jì)和建造時(shí),我們必須采用“避險(xiǎn)策略”來(lái)減少對(duì)材料和能源的普遍消耗和開(kāi)采。此外,我們必須捫心自問(wèn):真的需要一座新建筑嗎?能否使用現(xiàn)有的建筑?能否將一座舊建筑改造賦予它新的功能?能否將建筑物改造成多功能用途或長(zhǎng)期用途?

當(dāng)我們進(jìn)行改造、更新或建造時(shí),應(yīng)當(dāng)使用碳足跡較低的材料,例如吸收和儲(chǔ)存CO2的生物材料,或者應(yīng)當(dāng)重復(fù)使用那些通常會(huì)遭廢棄的材料。在這個(gè)意義上,我們必須考慮所使用的材料的方方面面。它們是如何提取、種植或采集的,如何制造、加工、運(yùn)輸?shù)模克鼈兊臄?shù)量足夠嗎?可再生嗎?它們?cè)诒馗魺帷⑹覂?nèi)氣候等方面是否符合我們的期望或需求?

盡管我們必須忽略現(xiàn)代建筑業(yè)所建立的許多“成功參數(shù)”,諸如工業(yè)化技術(shù)的效率、建筑標(biāo)準(zhǔn)和材料性能等,但仍然需要關(guān)注它們所帶來(lái)的品質(zhì)優(yōu)勢(shì)。例如,獲取清潔水、衛(wèi)生設(shè)施、日光和新鮮空氣等為代表的生活水平的普遍改善,絕不能被犧牲。人道主義和環(huán)境可持續(xù)性緊密相連,在建筑的絕對(duì)可持續(xù)性方面,它們必須被平等考慮。

3 從普適到本地化

實(shí)現(xiàn)被認(rèn)為具有絕對(duì)可持續(xù)性的建筑解決方案的一個(gè)最主要挑戰(zhàn)可能是:如何將人文理想與我們“重建”后的對(duì)負(fù)責(zé)任的材料使用的認(rèn)識(shí)結(jié)合起來(lái)?也許這需要重新審視我們的本地建筑的地域性?

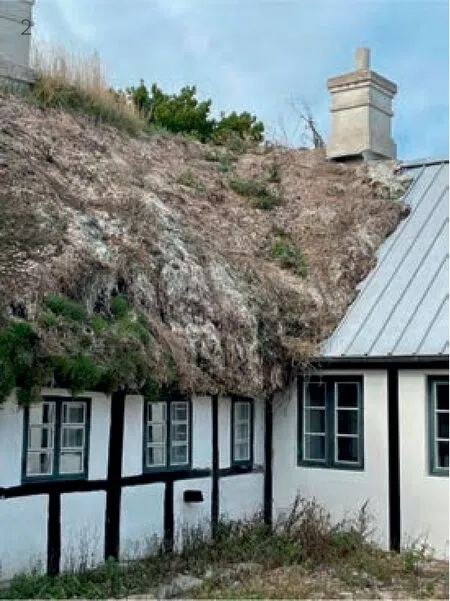

在工業(yè)化生產(chǎn)成為主流之前,建筑發(fā)展是基于當(dāng)?shù)刂R(shí)、工藝和地區(qū)建筑傳統(tǒng)的,這些傳統(tǒng)建筑與工業(yè)化建筑相比,經(jīng)過(guò)了數(shù)千年的培育、測(cè)試和完善。例如,北歐地區(qū)使用木材、稻草、海草和石頭有著充分的理由。這些材料易于獲取,并有效地為人們提供了避寒的居所(圖2)。其他例子包括夯土和日曬土,在一些非洲地區(qū),它們唾手可得,傳統(tǒng)上被用作建造遮陽(yáng)庇護(hù)所的建筑材料。此外,埃塞俄比亞使用編織的稻草作為建造圓形土庫(kù)爾小屋的主要材料[6]。

2 古老與創(chuàng)新的技術(shù)在丹麥L?s?島相遇 Old and new technologies meet on the Danish island of L?s?

本地化的建筑實(shí)踐的演變基于當(dāng)?shù)厝丝诘幕拘枨蟆⑽幕⒐に嚭唾Y源獲取方式。尋求更加可持續(xù)的建造方法,我們需要重新喚起對(duì)這類(lèi)策略的認(rèn)識(shí)。然而,這并不意味著抹殺我們邁向更好生活水平的努力。最終,我們需要將這些洞察與對(duì)當(dāng)?shù)刭Y源的獲取和與現(xiàn)實(shí)背景相關(guān)的專(zhuān)業(yè)知識(shí)結(jié)合起來(lái)。

材料的稀缺性和謹(jǐn)慎利用現(xiàn)有的材料并非建筑施工歷史上的新現(xiàn)象。事實(shí)上,只有少數(shù)社會(huì)在一段時(shí)間內(nèi)忽略了這一點(diǎn)。使用當(dāng)?shù)乜色@得、可再生且能夠改良或充分利用現(xiàn)有材料一直是最有效和可持續(xù)的建筑方法。

4 從灰色到多彩

從美學(xué)角度來(lái)看,這種更新的策略可能帶來(lái)更有趣、更具觸感和更易于相關(guān)者參與的建筑。也許通過(guò)清晰可辨的材料構(gòu)建的建筑甚至可以使我們嗅到、感受到、理解周?chē)牟牧虾蜆?gòu)筑物,重新建立與自然更緊密的聯(lián)系(圖3)。

3 在致力于絕對(duì)可持續(xù)建筑的建造中,避免過(guò)度使用技術(shù),轉(zhuǎn)而使用未經(jīng)處理或重復(fù)使用的材料,它們提供了豐富、隨 時(shí)間不斷變化的顏色和紋理 When building with an aim towards absolute sustainable architecture and to avoid excessive technologies,natural,untreated materials,or reused materials offer a wide range of colours and textures,that keep changing over time

這甚至可能會(huì)產(chǎn)生更加豐富多彩、富有冒險(xiǎn)精神和動(dòng)態(tài)張力的建筑。木材會(huì)隨著時(shí)間和溫度的變化而膨脹、收縮,木結(jié)構(gòu)表面可以追溯到相關(guān)信息。生物材料會(huì)對(duì)其周?chē)h(huán)境產(chǎn)生反應(yīng)并改變顏色。嶄新的茅草屋頂是鮮黃色的,而老舊的則變?yōu)榛疑P律a(chǎn)的材料可以按照人喜歡的顏色定制生產(chǎn),而重復(fù)使用的材料則呈現(xiàn)出隨機(jī)的拼貼圖案(圖4)。如果您選擇優(yōu)雅而懷

4 重復(fù)使用的木材充滿(mǎn)了來(lái)自其過(guò)去生活的各種變化和故事 Reused wood is full of varieties and stories from its past life

And when we transform,refurbish or build -we must use materials that have a low carbon footprint,such as biogenic materials that absorb and store CO2,or we must reuse materials that would normally become waste.In this sense,we must consider all aspects of the materials we intend to use.How are they extracted,cultivated or harvested? How are they manufactured? How are they processed? Where are they transported from and how? Is there enough of the materials? Are they renewable? And do they meet our expectations or needs in terms of insulation,indoor climate,etc.?

Although we must disregard many of the "parameters of success" that led to the ideas upon which the modern construction industry was founded,such as the efficiency of the industrialised technology,the building standards,and the material performances,we still need to pay attention to the qualities offered by them.For instance,a general improvement in living standards,in the form of universal access to clean water,sanitation,daylight,and fresh air,must not be sacrificed.Humane and environmental sustainability are deeply intertwined and must be considered on equal terms when it comes to absolute sustainability in architecture.

3 From Universal to Local

One overriding challenge to achieving architectural solutions that can be claimed to offer absolute sustainability might be: how to combine humanistic ideals with our "re-established"knowledge of responsible material use? Perhaps this would require revisiting our local building vernaculars?

Before industrialised production of buildings became dominant,development in construction was based on local knowledge,craftsmanship and regional building traditions,which,in contrast to industrialised construction,have been cultivated,tested and refined over thousands of years.For instance,the Nordic regions use wood,straw,eel grass and stone for good reasons.These materials were easy to get hold of and efficiently sheltered people from the cold,harsh climate (Fig.2).Other examples are rammed and sundried earth,which have traditionally been used in some African regions as the obvious building material for creating shelter from the sun.Then there is braided straw like that used in Ethiopia as the primary material for building round Tukul huts[6].

The evolution of local building practices is based on the local population’s basic needs,culture,craftsmanship and access to resources.As we seek to build more sustainably,we need to reawaken these types of strategies.However,this does not mean erasing our progress towards better living standards.Ultimately,we need to combine these insights with our access to local resources and knowhow linked to the present context.

Material scarcity and careful use of what is to hand is not a new phenomenon in the history of building construction.In fact,it has only been ignored by a few societies,and only for a time.

Building with materials that are locally available,renewable,and that transform or improve what you already have has always been the most efficient and sustainable approach to building.

4 From Grey to Multi-Coloured

Aesthetically,this renewed strategy might bring us architecture that is more interesting,tangible and easier for users to engage with.Architecture made from materials that are clear and recognisable.Perhaps even architecture that re-establishes a closer connection with nature by enabling us to smell,feel,sense and understand the materials and structures that surround us (Fig.3).

It might even lead to more colourful,adventurous,and dynamic architecture.Wood expands and contracts over time depending on the temperature,which can be traced in the surfaces of a wooden structure.Biogenic materials react to their surroundings and change colour.A brand-new thatched roof is bright yellow,while an older one is grey.Newly produced materials can be ordered in exactly the colour you prefer,while reused materials come with a random patchwork (Fig.4).If you transform an existing building elegantly and respectfully,its history will help shape its future use and give it aesthetic character.

There are cultural values linked to biogenic materials,transformations,and local building practices.By using these elements,we might be able to establish a closer link between buildings,有敬意的方式改造現(xiàn)有建筑,它的歷史將有助于塑造其未來(lái)的用途,賦予其美學(xué)特質(zhì)。

這些都具有與生物材料、轉(zhuǎn)化和當(dāng)?shù)亟ㄖ?shí)踐相關(guān)的文化價(jià)值。通過(guò)使用這些元素,我們或許能夠在房屋、建筑和人之間建立更緊密的聯(lián)系。它甚至可能促進(jìn)使用者與其家園之間的直覺(jué)聯(lián)系,因?yàn)樗诓牧稀⒔ㄔ旆绞胶蜌v史等方面都與當(dāng)?shù)匚幕嚓P(guān)聯(lián)。這將激勵(lì)使用者更好地照顧他們的家園,延長(zhǎng)其使用壽命。

5 從完美到靈活

作為建成環(huán)境的專(zhuān)業(yè)人士和利益相關(guān)者,我們所受的教育讓我們要去想象完成的項(xiàng)目。像現(xiàn)代主義者一樣,我們被自己想要實(shí)現(xiàn)的理念所驅(qū)使,這些理念指導(dǎo)著我們進(jìn)行設(shè)計(jì)和建造。我們?cè)O(shè)想,然后努力實(shí)現(xiàn)“一座完美的建筑,在完美的廣場(chǎng)上,美麗的人們?cè)谝粋€(gè)陽(yáng)光明媚的春日里在其周?chē)顒?dòng),使用它”。最好的贊美是看到它被建造并完全按照原始草圖中描述的方式被使用。然而,這既不是建筑的運(yùn)作方式,也不是我們能夠去理解的它們?cè)谏芷趦?nèi)與使用者的互動(dòng)方式。

盡管具有長(zhǎng)壽命的建筑本身更加可持續(xù),但實(shí)際上很難估計(jì)哪些建筑將有最長(zhǎng)的壽命。通常,最受人喜愛(ài)的建筑具有最長(zhǎng)的壽命。因?yàn)槿藗儗?duì)它們有一種主人翁意識(shí),關(guān)心它們,并努力讓建筑適應(yīng)自己的使用和需求。生命周期分析(LCA)做得最好的建筑不一定是壽命最長(zhǎng)、生命周期影響最大的建筑。

為了在地球邊界內(nèi)運(yùn)行,我們必須改變看待建筑及其在社會(huì)中作用的方式(圖5)。我們?cè)谠O(shè)計(jì)和建造建筑時(shí),是否應(yīng)該追求靈活性、適應(yīng)性、空間品質(zhì)和美感,而不是追求完美、永恒的標(biāo)志性?使用當(dāng)?shù)氐摹⒖稍偕暮涂色@得的材料是否意味著我們的建筑就需要永恒不變?如何才能澄清我們對(duì)理想的響應(yīng)式建筑的認(rèn)識(shí),從而使我們只在有充分理由的情況下使用新材料?

5 粘土板可以通過(guò)天然染色改變表達(dá) Clay plates can change expression through natural dye

6 靈感取代標(biāo)準(zhǔn)

在創(chuàng)新設(shè)計(jì)和建造方式時(shí),我們必須敢于重新思考我們的理想和相關(guān)規(guī)定。我們不能讓法規(guī)和工業(yè)標(biāo)準(zhǔn)的上限或下限來(lái)定義建筑的目的,更不能任由它們定義我們的設(shè)計(jì)、改造和建造方式。當(dāng)下的建筑法規(guī)和標(biāo)準(zhǔn)不應(yīng)阻撓新的解決方案,盡管法律框架本質(zhì)上是保守的。它們純粹無(wú)法滿(mǎn)足當(dāng)前和未來(lái)對(duì)建筑業(yè)可持續(xù)轉(zhuǎn)型的需求。這一點(diǎn)在審視回收材料的再利用機(jī)會(huì)時(shí)尤為明顯,因?yàn)榛厥詹牧系奈镔|(zhì)屬性必須符合新材料的標(biāo)準(zhǔn),而這幾乎是不可能的。

因此,建筑絕對(duì)可持續(xù)發(fā)展的最重要的切入點(diǎn)或許不是確定其標(biāo)準(zhǔn)和美學(xué),也不是將其建筑實(shí)踐系統(tǒng)化。相反,我們應(yīng)該制定戰(zhàn)略和共識(shí),幫助建筑業(yè)更好地在地球邊界內(nèi)運(yùn)轉(zhuǎn),并激發(fā)創(chuàng)造新的可持續(xù)解決方案。我們需要釋放我們的創(chuàng)造力,重新發(fā)現(xiàn)傳統(tǒng)的建筑技術(shù),重新考慮我們的材料資源,以全新的方式建造與今天截然不同的建筑(圖6、7)。建成案例具有強(qiáng)大的影響力,相關(guān)法規(guī)需要為截然不同的實(shí)踐留出空間,這不需要成本高昂的額外的編制工作,我們想要擺脫那些構(gòu)成了現(xiàn)行標(biāo)準(zhǔn)和法規(guī)基礎(chǔ)的先例。□(本文的主要內(nèi)容與《無(wú)為創(chuàng)新——引領(lǐng)建筑環(huán)境可持續(xù)變革所需的能力》[7]一書(shū)有著密切聯(lián)系。)architecture and people.It may even promote an intuitive attachment between a user and their home thanks to the local cultural connection to its materials,building methods and history.And this might inspire the user to take better care of their home and thereby extend its lifetime.

6 不同形狀和形式的夯土變化 Variations of rammed clay in different shapes and forms

7 茅草屋頂?shù)奶貙?xiě) Close up of a thatched roof

5 From Perfection to Flexibility

As professionals and stakeholders in the built environment,we are taught to visualise the finished project.Like the Modernists,we are driven by ideas that we want to turn into built reality,and it is these ideals that guide us through the design and building processes.We imagine and then strive to realise "a perfect building in a perfect square with beautiful people who use it and move around on it,on a sunny spring day".And with no better compliment than to see it built and used exactly as depicted in the original sketches.However,this is not how buildings work nor is it how we can understand their interaction with users throughout a lifetime.

While buildings with a long life span are in themselves more sustainable,in reality it is difficult to estimate which buildings will live the longest.Often,it is the buildings that are most loved that have the greatest longevity.Because people feel an ownership towards them,care for them and make an effort to adapt them to their uses and needs.The buildings with the best Life Cycle Analysis (LCA)are not necessarily the ones with the longest life span and the best life cycle impact.

To navigate within the planetary boundaries,we must change the way we look at architecture and its role in society (Fig.5).Instead of striving for perfect,everlasting iconic buildings,should we instead look for flexibility,adaptability,spatial qualities,and beauty when we design and build? Does using materials that are local,renewable and available mean that our buildings then need to last forever? How can we clarify our perceptions of an ideal responsive architecture,so that we only use new materials for good reasons?

6 Inspiration Instead of Standards

When innovating the ways in which we design and build,we must dare to rethink our ideals and our formal regulations.We cannot allow regulations and minimum or maximum industrial standards define the purpose of architecture,and thus how we design,transform and build.Today’s building regulations and standards should not hinder new solutions,since legal framework is by nature conservative.They simply do not respond to current and future demands for the sustainable transformation of the construction industry.This is particularly evident when looking at the opportunities for reusing salvaged materials,which is almost impossible due to the fact that their material properties must match the standards of new materials.

Consequently,the most important perspective on absolute sustainability in architecture is,perhaps,not to define its standards and aesthetics or to systemise its building practices.Instead,we should formulate strategies and understandings that help the construction industry to better navigate within the planetary boundaries and that inspire the creation of new sustainable solutions.We need to set our creativity free,rediscover traditional building techniques,and reconsider our material resources in order to build in new ways that are radically different to what we do today (Fig.6,7).Built examples have a powerful effect,and the regulations need to make room for a completely changed practice,without having to go through costly extra documentation,which is not required by the practices we want to get rid of because they form the foundation for current standards and regulations.□ (The main content of this paper is closely related to the book Innovation of Nothing: The capabilities needed to lead sustainable change in the built environment[7].)