學校聯結與抑郁的關系:一項三水平元分析

孟現鑫 陳怡靜 王馨怡 袁加錦 俞德霖

摘? 要? 以往關于學校聯結與抑郁關系的理論和實證研究結果均不一致。為明確兩者間的整體關系, 探索造成分歧的原因, 對納入的87項研究進行了三水平元分析。結果發現, 學校聯結與抑郁存在顯著負相關(r = ?0.39, df = 205, p < 0.001)。此外, 學校聯結和抑郁的關系受被試性別、年齡、抑郁測量工具、研究數據屬性的調節, 但不受學校聯結測量工具、文化類型、發表年份的調節。本研究首次使用三水平元分析技術整合了學校聯結與抑郁的關系, 理論上為兩者關系提供了階段性定論, 實踐上為預防和干預個體抑郁提供了參考依據。

關鍵詞? 學校聯結, 抑郁, 三水平元分析, 社會控制理論, 社會計量器理論, 自我決定理論

分類號 ?R395

1? 前言

世界衛生組織(World Health Organization, WHO)指出, 抑郁是加重各國疾病負擔的主要因素, 全球約有2.8億人被抑郁困擾, 占總人口的3.8% (World Health Organization, 2023)。抑郁不僅會導致個體學習和工作效率低下, 而且會導致人際交往障礙甚至自殺(Thapar et al., 2012; Kieling et al., 2019)。為了有效預防和干預抑郁, 以往研究探討了諸多與其密切相關的因素, 其中學校聯結是備受關注的因素之一(He et al., 2019; Joyce & Early, 2014; Shochet et al., 2006)。學校聯結(School Connectedness)是指學生在學校中所感知到的接納、尊重、支持和包容(Goodenow, 1993), 反映了學生對學校的認知以及與校內成員的情感聯系程度(殷顥文, 賈林祥, 2014)。目前, 多數理論認為學校聯結是降低抑郁水平的保護性因素(Gerard & Booth, 2015; Leary, 2005; Sandler, 2001); 但也有理論認為, 學校聯結對抑郁沒有保護作用, 甚至起反作用(Datu et al., 2023; Davis et al., 2019; Loukas et al., 2006)。與此一致, 學校聯結與抑郁的實證研究既有報告負相關結果、正相關結果, 也有報告無相關結果。綜上, 學校聯結與抑郁的關系在理論觀點和實證研究上均存在分歧。為解決學校聯結與抑郁關系間的爭議, 本研究采用元分析技術(meta-analysis)定量整合學校聯結與抑郁的關系, 并且分析可能影響二者關系的因素, 從而為抑郁的預防和干預提供依據。

1.1? 學校聯結與抑郁的關系及其理論模型

目前, 主要有社會控制理論(Social Control Theory)、社會計量器理論(Sociometer Theory)、自我決定理論(Self-Determination Theory)和社會支持的源一致理論(Source Congruence Theory)論及了學校聯結與抑郁的關系。

社會控制理論認為個體與社會組織的聯結程度越強, 該組織對個體的心理和行為的影響就越大(Hirschi, 1996)。根據這一觀點, 個體的學校聯結越強, 其情緒與健康受學校的影響越大。具體而言, 學校聯結程度高的個體更愿意遵守校紀, 能與老師、同學形成更好的聯結以獲得情感支持, 從而有助于緩解或削弱壓力事件產生的消極情緒, 降低患有抑郁的風險(McLaren et al., 2015)。McLaren等人(2015)發現, 學校聯結可以有效促進積極的同伴聯結, 從而減少抑郁的產生。社會計量器理論提出, 那些認為人際關系重要的個體傾向于建立積極的人際關系, 從而獲得更多的社會支持、產生較少的消極情緒(Leary, 2005)。學校聯結程度高的個體往往能夠認識和感受到人際關系的重要性, 這有助于減少其消極情緒和罹患抑郁的風險。Shochet等人(2011)發現, 在校感受到的人際關系質量和被接納程度越高, 個體的抑郁水平越低。自我決定理論認為個體希望自己在所處的環境中能感受到來自他人的愛和關懷, 感受到自己屬于組織中的一員。這種歸屬感的滿足有助于降低個體的消極情緒和提高個體的心理健康水平(Ryan & Deci, 2017)。學校聯結能滿足個體對歸屬感的需要, 從而緩解壓力產生的不良情緒, 降低個體罹患抑郁的風險。與此相一致, Parr等人(2020)發現積極學校聯結可以通過滿足個體的一般歸屬感來降低抑郁水平。

與社會控制理論、社會計量器理論和自我決定理論的觀點不同, 社會支持的源一致理論認為, 若壓力源和社會支持的來源一致時, 社會支持對壓力的緩沖作用可能無效(Lebow, 2005; Rueger et al., 2016)。具體而言, 與學校的聯結可能促使個體更關注來自學校領域的他人評價(Vannucci & McCauley Ohannessian, 2018), 而當引起抑郁情緒的壓力來自學校時(比如, 學業和人際關系), 學校聯結程度高的個體可能會抑制抑郁情緒的表達以符合學校期待(周文潔, 2013)。此時, 學校聯結不僅可能無法減少抑郁情緒, 甚至導致抑郁情緒的累積, 表現為社會支持的反轉緩沖效應(Reverse Buffering Effects of Social Support) (Lebow, 2005; Rueger et al., 2016)。與此一致, Datu等人(2023)的研究發現在期末考核階段, 隨著學校聯結程度的提高, 學生報告了更高的抑郁水平。

根據以上理論, 學校聯結通過與其他因素的相互作用, 影響個體的抑郁水平。但是學校聯結與抑郁的具體關系如何尚不清楚, 兩者的關系具體受哪些因素影響仍有待討論。

1.2? 學校聯結與抑郁關系的調節變量

學校聯結與抑郁的關系存在不一致的結果, 可能與研究對象特征(性別、年齡)、研究的測量因素(測量工具、研究數據屬性)、研究背景特征(文化、時代)有關。

性別可能調節學校聯結與抑郁的關系。在社會化過程中, 女性被鼓勵依賴和與他人建立親密關系(Davis et al., 2019), 而男性則被鼓勵獨立和自主(Bakan, 1966; Barbee et al., 1993)。在學校中, 女性比男性更傾向從教師和同學等校內成員中尋求支持以應對壓力產生的不良情緒(Yang et al., 2021)。因此, 與男性相比, 學校聯結對女性抑郁的影響可能更大。與此相一致, He等人(2019)發現, 學校聯結對女性抑郁的影響程度更大。綜上, 本研究假設相比于男性, 學校聯結對女性抑郁的影響更大。年齡也可能影響學校聯結與抑郁的關系。隨著年齡增加, 來自學校的壓力增強(如學業壓力、同伴競爭等), 這會降低個體對學校的認同和對同伴關系的維護, 進而削弱個體的學校聯結水平(Oelsner et al., 2011), 導致學校聯結對個體的抑郁保護作用降低(Henrich et al., 2005; Xu & Fang, 2021)。與此相似, Rose等人(2022)發現, 相比中學生, 學校聯結對小學生心理健康的保護作用更大。綜上, 本研究假設隨年齡增長, 學校聯結對抑郁的保護作用減弱。

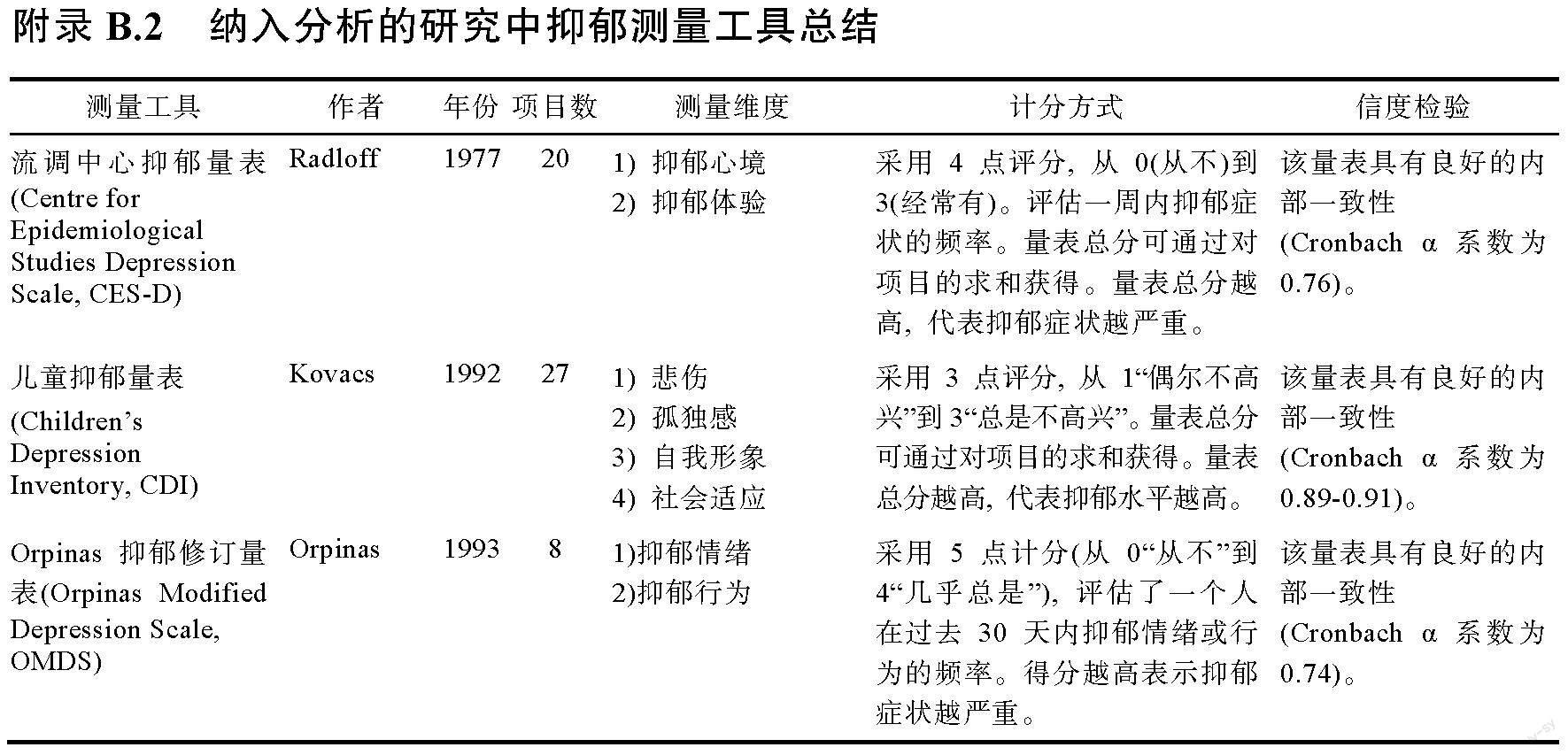

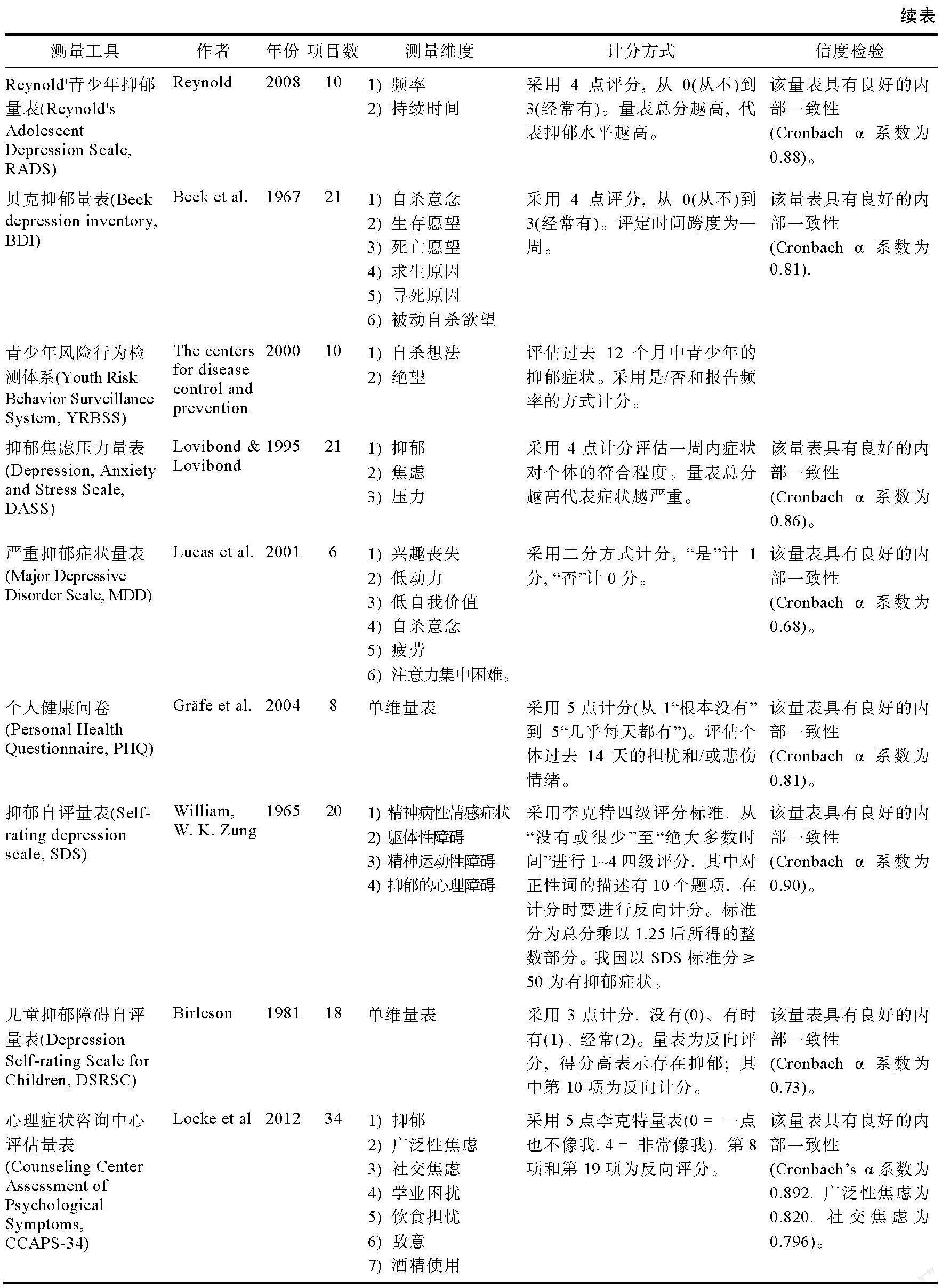

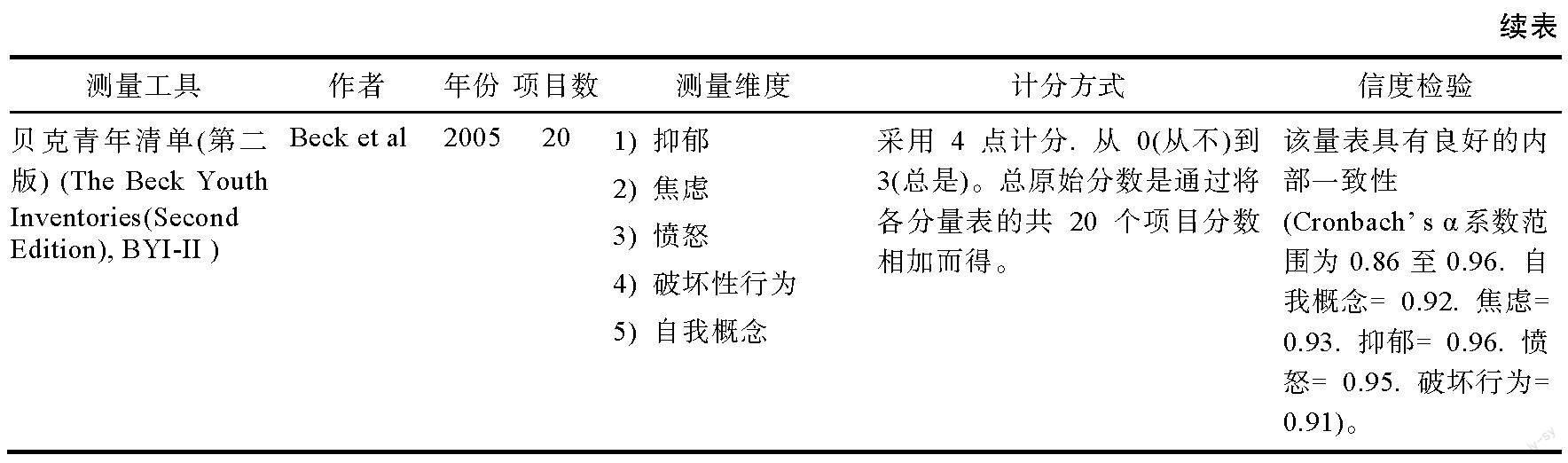

研究的測量因素(測量工具、研究數據屬性)可能影響學校聯結與抑郁的關系。測量工具可能調節學校聯結與抑郁的關系。測量學校聯結的工具主要有學校歸屬感問卷(Psychological Sense of School Membership Scale, PSSM)和學校聯結量表(School Connectedness Scale, SCS)。PSSM量表由18個項目組成, 它測量的是學生在學校所感知的被接納程度、師生關系和同伴關系(Goodenow, 1993)。SCS量表由6個項目組成, 它測量的是學生學校歸屬感與教師支持(Resnick et al., 1997)。不同學校聯結的測量工具在內容和項目數量上均有不同, 這可能影響測量的結果。其次, 測量抑郁的工具主要有兒童抑郁量表(Childrens Depression Inventory, CDI)、流調中心抑郁量表(Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale, CES-D)和Orpinas抑郁修訂量表(Orpinas Modified Depression Scale, OMDS)。CDI由27個項目組成, 它主要測量的是兒童悲傷、孤獨感、自我形象和社會適應(Sitarenios & Kovacs, 1999); CES-D由20個項目組成, 它測量的是一般人群一周內抑郁癥狀的頻率, 側重評估抑郁的心境和體驗(Radloff, 1977); 而OMDS由8個項目組成(Orpinas, 1993), 它主要測量的是個體過去30天的抑郁情緒和抑郁行為。各抑郁量表的結構和測量內容不同, 這可能影響學校聯結與抑郁的關系。因此, 本研究假設學校聯結的測量工具和抑郁的測量工具均能調節學校聯結與抑郁的關系。

研究數據屬性可能調節學校聯結與抑郁的關系。根據數據屬性不同, 研究數據可以分為橫斷數據和縱向數據。前者是指研究變量均在同一時間點測量并獲取的數據; 后者是指研究變量在不同時間點測量并獲取的數據(陳春花 等, 2016)。數據屬性能夠對變量關系造成較大影響, 具體而言, 縱向數據比橫斷數據具有更強的因果關聯性(張建平 等, 2020)。與橫斷數據相比, 變量間的關系在縱向數據中往往呈現衰減或累積效應。目前多項縱向研究發現, 隨著數據收集時間推移, 學校聯結與抑郁的負相關程度減弱(Goering & Mrug, 2022)。這表明學校聯結和抑郁的關系在時間上可能存在衰減效應。因此, 本研究假設, 相較于橫斷數據, 學校聯結與抑郁在縱向數據中相關程度更小。

研究背景特征(文化、時代)可能影響學校聯結與抑郁的關系。就文化因素而言, 中國集體主義文化強調人的互依性; 西方個人主義文化強調人的獨立性(黃梓航 等, 2018; Hofstede, 1980)。與重視個體自由選擇的西方文化相比(黃梓航 等, 2018; Hofstede, 1980), 中國文化下的個體普遍為集體主義文化的依存型自我構念, 他們更關注自己與他人的聯結, 更渴望被集體接納和支持(Chen et al., 2003; Markus & Kitayama, 2014)。因此, 相比于西方, 積極的學校聯結更有助于中國個體的心理社會適應, 減少抑郁情緒。與此相似, 有研究表明, 相較于個人主義文化, 集體主義文化下積極的情感聯結與個體心理健康水平相關程度更大(Park et al., 2013)。因此, 本研究假設相較于西方文化, 在中國文化下學校聯結與抑郁的相關程度更強。

就時代因素而言, 在生態系統理論中, 時間系統(chronosystem)強調應當將時間和環境相結合來考察個體的心理和行為發展的動態過程。隨時代發展與社會變遷, 來自學校的壓力增加(如學業壓力、同伴競爭等) (俞國良, 王浩, 2020), 這在一定程度上將削弱學校聯結對抑郁的保護作用。因此, 本研究假設隨發表年份增長, 學校聯結與抑郁的相關程度減弱。

1.3? 研究目的與研究問題

綜上, 本研究采用元分析技術對現有學校聯結與抑郁關系的研究進行梳理和分析, 從宏觀的視角定量確認學校聯結與抑郁關系的強度以及潛在影響因素。這在理論上有利于澄清爭議, 在實踐上可以為抑郁的干預措施提供證據支持。本研究將運用元分析方法關注兩個核心問題:其一, 學校聯結與抑郁是否相關以及相關程度如何; 其二, 探討兩者關系是否受到研究對象特征(性別、年齡)、研究的測量因素(測量工具、研究數據屬性)、研究背景特征(文化、時代)的調節。

2? 研究方法

為保證元分析的系統性和可重復性, 本研究根據PRISMA 2020聲明進行文獻檢索、篩選、編碼、質量評價以及發表偏倚評估, 并報告結果(Page et al., 2021)。

2.1? 文獻檢索與篩選

本研究旨在探討學校聯結與抑郁的關系。目前, 學校聯結與學校歸屬感在研究中經常互換使用(Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Goodenow & Grady, 1993; Libbey, 2004; Korpershoek et al., 2020)。因此, 為保證納入的文獻足夠全面, 本研究首先在檢索中文數據庫時(中國知網、萬方期刊數據庫及維普期刊數據庫), 將關鍵詞“學校聯結” “學校歸屬”分別與“抑郁”組合進行檢索; 其次在英文數據庫中(Web of Science, PubMed和Science Direct)以關鍵詞“school connectedness” “school belonging”分別與“depress”或“depression”組合進行檢索; 最后, 將文獻閱讀時發現的相關文獻予以補充。檢索截止日期為2023年6月19日, 最終獲得文獻1131篇。

使用EndNote X9導入文獻并按照如下標準篩選: (1)文獻類型為量化實證研究, 排除理論綜述、會議摘要、個案研究以及質性研究; (2)只納入報告了學校聯結與抑郁得分之間的相關系數(r)的研究; (3)樣本量明確; (4)數據重復發表僅選其中一篇, 如學位論文以期刊論文形式發表在學術刊物上且報告了數據, 則以發表的期刊論文為準, 反之采用學位論文的數據; (5)如果在符合本研究主題的原始研究中沒有報告符合要求的效應量, 但向作者索要后獲得相關系數r的, 也納入分析。文獻篩選流程見圖1。

2.2? 文獻編碼與質量評價

首先, 每項研究根據以下特征由兩位作者獨立進行編碼: (A)作者; (B) 研究數據屬性(橫斷數據/縱向數據); (C)發表年份; (D)文化類型(參照Hofstede (1984)報告的文化數據, 將樣本中的美國、澳大利亞、加拿大、英國、德國歸類為西方國家); (E)性別(女性在樣本中的百分比); (F)平均年齡(測量抑郁時樣本的平均年齡); (G)測量學校聯結的工具(如PSSM, SCS等); (H)測量抑郁的工具(如CDI, CES等); (I)效應量(相關系數)。并且, 在編碼時遵循以下原則: (1)若研究根據被試特征分別報告效應量, 則分別編碼(如分開報告男性和女性的效應量); (2)每個獨立樣本進行一次編碼, 若研究報告了多個獨立樣本, 則逐個編碼; (3)若研究對多個變量指標進行測量, 則分別編碼。隨后, 將兩位作者獨立完成的編碼表進行Kappa評分者信度檢驗以評估編碼一致性。經計算, 兩份編碼表的Kappa系數為0.963, 一致性較高。最后, 由全體作者討論后確定兩份編碼表中不一致的編碼。

其次, 文獻質量分析參照美國國立衛生研究院(National Institutes of Health, NIH)的縱向和橫斷研究質量評估工具(Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies), 對納入分析的研究依次評估, 并以符合標準(記1分)或不符合標準(記0分)進行計分(National Institutes of Health, 2014)。橫斷研究的評價總分介于0~8之間, 縱向研究的評價總分介于0~14之間。研究質量評分結果見網絡版附錄A, 評分越高表明文獻質量越好。

2.3? 效應量計算

本研究依次從納入分析的研究中提取學校聯結與抑郁的相關系數。由于相關系數不符合正態分布, 本研究在計算主效應或調節效應時將所有相關系數轉為Fishers z分數(Cooper et al., 2019)。數據分析后, 再將Fishers z分數轉為相關系數以便解釋。本研究在解釋相關系數大小時, 依照Cohen (1992)的標準, 以0.10、0.30和0.50為臨界值, 分別判定小、中和大的效應量。

2.4? 模型選擇

本研究所納入元分析的大多數原始文獻報告了多個效應量。同一研究中報告的多個效應量往往來自同一樣本, 因此效應量之間是相關的。值得注意的是, 傳統元分析方法假設各效應量之間相互獨立, 在一項研究中只提取一個效應量(Assink & Wibbelink, 2016)。這種元分析方法忽略了這種相關, 可能會導致總體效應量被高估(Lipsey & Wilson, 2001)。相較于傳統元分析方法, 三水平元分析模型考慮了同一研究中效應量的依賴性, 將效應量的方差來源進一步分解為三個水平。水平1是納入分析的原始研究在抽取樣本時由抽樣方法引起的誤差。水平2源于同一研究所報告的多個效應量之間的差異, 若顯著, 則表明同一研究的不同效應量具有異質性; 水平3源于不同研究所報告的效應量之間的差異, 若顯著, 則表明不同研究的效應量具有異質性(Cheung, 2014)。因此, 相較于傳統的元分析方法, 三水平元分析方法能夠處理來自同一研究效應量之間的依賴性問題, 從而最大化地保留信息, 提高統計檢驗力(Assink & Wibbelink, 2016)。基于上述原因, 本研究將使用三水平元分析模型進行主效應檢驗、異質性檢驗、調節效應檢驗、發表偏倚檢驗以及敏感性分析。

2.5? 異質性檢驗與調節效應檢驗

本研究將使用單側對數似然比檢驗(one tailed log likelihood ratio tests)對水平2方差和水平3的方差進行分析, 以確定其是否顯著, 若顯著, 則可以進一步進行調節效應檢驗, 以確定異質性的來源(Gao et al., 2023)。本研究將調節變量作為協變量加入三水平元分析模型, 以估計其調節效應大小(Gao et al., 2023)。本研究的調節變量涉及: (1)連續調節變量: 樣本中女性被試數占總被試數的比例、樣本的平均年齡、發表年份。(2)分類調節變量: 學校聯結的測量工具、抑郁的測量工具、研究數據屬性、文化類型。本研究根據Card (2012)的建議設置調節變量水平, 各水平的效應量個數不少于5, 以此保證調節效應結果的代表性。

2.6? 發表偏倚控制與檢驗

發表偏倚是指具有統計學意義的研究結果更容易發表(Franco et al., 2014)。發表偏倚是客觀存在的, 因此研究者常常采用多種方法檢驗(Reed et?al., 2015)。本研究將分別使用漏斗圖(funnel plot)、Egger-MLMA回歸法和剪補法對發表偏倚進行定性和定量評估。定性評估時, 若漏斗圖呈對稱的倒漏斗狀, 則表明發表偏倚較小(Sterne & Harbord, 2004)。在納入分析的效應量間非相互獨立時, 與傳統Egger回歸法相比, Egger-MLMA回歸法更能有效控制I類錯誤(Rodgers & Pustejovsky, 2021)。鑒于納入分析的研究大多報告了彼此相關的多個效應量, 本研究選用Egger-MLMA回歸法。若Egger-MLMA回歸結果不顯著, 則表明發表偏倚較小(Rodgers & Pustejovsky, 2021)。當Egger-MLMA回歸顯著(p < 0.05)或漏斗圖呈現效應量不對稱分布, 則采用剪補法檢驗出版偏倚給元分析結果造成的影響, 若剪補后的效應量未發生顯著變化, 則可認為該元分析結果受發表偏倚影響較小(Duval&Tweedie, 2000)。

2.7? 敏感性分析

納入元分析的研究報告學校聯結與抑郁的相關系數從?0.74到0.14, 結果差異大。這提示當前元分析結果存在受到異常值影響的風險, 可能導致虛假的統計結論(Kepes & Thomas, 2018)。為評估本元分析結果的穩健性, 本研究采用“去一法” (leave-one-out method)和三水平Cook距離法(Cooks distances method)剔除對元分析結果可能產生顯著影響的異常值, 并重新進行三水平元分析以衡量異常效應量和異常研究的影響(Viechtbauer & Cheung, 2010)。“去一法”的具體步驟為, 逐個剔除納入的效應量和原始研究, 并重新進行三水平元分析, 直到所有的效應量和原始研究均被剔除過(Dodell-Feder & Tamir, 2018)。Cook距離法的具體步驟為剔除Cook距離大于4/(n ? k ? 1)的效應量和原始研究并分別重新進行三水平元分析(Fox., 2019)。

2.8? 數據處理

本研究使用R 4.2.0的metafor包進行元分析(Viechtbauer, 2010)。R代碼來自Assink和Wibbelink (2016)以及Rodgers和Pustejovsky (2021)所發表的程序。本研究所有模型參數將采用限制性極大似然法(restricted maximum likelihood method)進行估計(Viechtbauer, 2010), 將雙尾p值小于0.05的結果界定為顯著。本研究數據處理過程中所使用到的公式見網絡版附錄C。

3? 研究結果

3.1? 文獻納入與質量評價

本研究共納入研究87項(含87個獨立樣本, 206個效應值, 177828名被試), 時間跨度為1999~2023年。納入文獻的基本信息見表1。納入的61項橫斷研究的文獻質量評價得分范圍在5分至8分, 均值為6.46分, 高于理論均值(4分); 納入的26項縱向研究的文獻質量評價得分范圍在7分至12分, 均值為10.23分, 高于理論均值(7分)。整體而言, 納入的文獻質量較好。

3.2? 主效應和異質性檢驗

當前元分析采用三水平元分析模型對學校聯結與抑郁的關系進行主效應估計。結果顯示, 學校聯結與抑郁之間呈顯著負相關(r = ?0.39, df = 205, p < 0.001), 95% CI [?0.41, ?0.34]。基于Cohen (1992)的標準, 該相關系數屬于中效應量。

研究內方差(水平2)和研究間方差(水平3)的顯著性采用單側對數似然比檢驗法確定。結果顯示, 研究內方差(水平2) (σ2 = 0.01, p < 0.001)和研究間方差(水平3) (σ2 = 0.02, p < 0.001)均存在顯著差異。在總方差來源中, 抽樣方差(水平1)為1.86%, 研究內方差(水平2)為31.41%, 研究間方差(水平3)為66.73%。因此, 可以分析調節變量以進一步解釋學校聯結與抑郁的關系。

3.3? 發表偏倚和敏感性檢驗

Egger-MLMA回歸的結果顯著(t = ?2.41, df = 204, p = 0.02), Egger-MLMA回歸的截距為?1.27, 95% CI [?2.31, ?0.23]。漏斗圖(圖2)顯示, 實際觀測的效應量呈不對稱分布, 為使漏斗圖呈對稱分布, 需要剪補55個效應量在漏斗圖右側。剪補55個效應量后重新進行三水平元分析, 結果顯示學校聯結與抑郁的主效應量(r = ?0.20, p < 0.001)小于剪補前的效應量(r = ?0.39), 但顯著性保持不變。

采用去一法逐個剔除納入的效應量并重新進行三水平元分析, 結果顯示, 剔除了Midgett和Doumas (2019)報告的一個相關系數后, 學校聯結與抑郁的相關程度最低(r = ?0.39, df = 204, p < 0.001); 剔除了Datu等人(2023)報告的一個相關系數后, 學校聯結與抑郁的相關程度最高(r = ?0.40, df = 204, p < 0.001)。逐個剔除納入的原始研究并重新進行三水平元分析, 結果顯示, 剔除了Datu等人(2023)報告的所有相關系數后, 學校聯結與抑郁的相關程度最高(r = ?0.40, df = 204, p?< 0.001); 剔除了Parr等人(2020)報告的所有相關系數后, 學校聯結與抑郁的相關程度最低(r = ?0.39, df = 203, p < 0.001)。無論逐個剔除納入的效應量, 還是逐個剔除納入原始研究進行敏感性分析, 結果發現, 剔除前與剔除后重新計算的主效應在顯著性上一致, 且都屬于中等強度的相關。

采用三水平Cook距離法對效應量進行影響性分析的結果顯示:存在10個效應值量可能對本元分析結果產生顯著異常影響。剔除上述效應量后, 重新進行三水平元分析, 結果顯示學校聯結與抑郁的相關程度為r = ?0.37, 且研究內方差(水平2) (σ2 = 0.01, p < 0.001)和研究間方差(水平3) (σ2 = 0.01, p < 0.001)均存在顯著差異。采用三水平Cook距離法對納入的研究進行影響性分析的結果顯示:存在4項原始研究可能對本元分析結果產生顯著異常影響。剔除上述4項研究后, 重新進行三水平元分析。結果顯示學校聯結與抑郁的相關程度為r = ?0.38, 且研究內方差(水平2) (σ2 = 0.01, p < 0.001)和研究間方差(水平3) (σ2 = 0.02, p < 0.001)均存在顯著差異。無論剔除異常效應值還是剔除異常研究, 結果均發現, 剔除前與剔除后重新計算的主效應在顯著性上一致, 且都屬于中等強度的相關。綜上所述, 從敏感性分析看, 當前元分析結果受異常值影響小, 較為穩健可靠。

3.4? 調節效應檢驗

利用元回歸分析檢驗調節變量對學校聯結與抑郁的關系是否存在顯著影響, 結果如表2所示。女性比例的調節效應顯著, F (1, 197) = 4.84, p = 0.03, 學校聯結與抑郁的負相關隨女性比例的增大而增大(β = ?0.00, p = 0.03)。研究數據屬性的調節效應顯著, F (1, 204) = 58.75, p < 0.001, 與縱向數據(r = ?0.27)相比, 在橫斷數據(r = ?0.42)下學校聯結與抑郁的相關程度更大。抑郁測量工具的調節效應顯著, F (4, 137) = 6.83, p < 0.001。在納入分析的研究中, 使用CDI量表測得的抑郁與學校聯結的相關程度最大(r = ?0.62); 使用OMDS量表測得的抑郁與學校聯結的相關程度最小(r = ?0.15)。使用CDI量表的效應量顯著大于使用CES-D的效應量(β = ?0.20, p < 0.001); 使用OMDS的效應量顯著小于使用CES-D的效應量(β?= 0.20, p < 0.05)。使用MFQ、RADS的效應量與使用CES-D的效應量沒有顯著差異。年齡的調節效應邊緣顯著, F (1, 175) = 3.83, p = 0.052, 學校聯結與抑郁的負相關隨年齡的增大而減小(β = 0.01, p = 0.052)。此外, 沒有發現其他顯著的調節效應。

4? 討論

4.1 ?學校聯結與抑郁的關系

盡管目前不少理論與實證研究已經探討了學校聯結與抑郁的關系, 但結果并不一致。研究間的分歧提示有必要整合既往結果, 以更宏觀的角度得出更確切的結論。本研究通過三水平元分析技術整合學校聯結與抑郁的相關研究。主效應結果顯示, 學校聯結與抑郁存在中等強度的顯著負相關。這與本研究的假設一致, 隨著學校聯結的增強, 個體的抑郁水平降低。該結果為兩者關系做出了階段性定論, 表明學校聯結是個體抑郁的重要保護因素, 支持社會控制理論、社會計量器理論和自我決定理論的觀點。需要注意的是, 漏斗圖和Egger-MLMA回歸的結果表明, 本研究可能受到發表偏倚的影響。剪補法檢驗結果表明主效應可能存在高估的傾向。

此外, 本研究元分析主效應在研究內(水平2)和研究間(水平3)的方差均顯著, 該結果說明主效應存在異質性。這提示在探討學校聯結與抑郁的關系時不得孤立看待主效應的結果(Harrer et al., 2021)。抑郁的產生是各種因素的累積而不是單一因素的作用(Wright & Masten, 2005), 學校聯結對抑郁的保護作用可能受其他因素影響而增強或減弱。因此, 需要進一步分析學校聯結與抑郁關系的潛在調節變量, 以解釋主效應的異質性, 從而更加全面地闡述兩者關系。

4.2? 學校聯結與抑郁關系的調節變量

調節效應檢驗結果顯示, 性別顯著調節學校聯結與抑郁的關系, 隨著女性樣本比例的增加, 學校聯結與抑郁的負相關強度顯著增加。該結果表明, 相較于男性, 學校聯結對女性的抑郁影響更大, 支持本研究假設。在社會化過程中, 女性往往傾向于將自己定義為關系的一部分; 而男性則傾向于將自己定義為與關系相分離的個體(Davis et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2021)。相較于男性, 女性在學校中更傾向從教師和同學中尋求支持以應對壓力產生的不良情緒反應(Yang et al., 2021)。因此, 相比男性, 學校聯結對女性的抑郁有更強的保護作用。與此相一致, Allen等人的元分析(2018)發現, 相比男性, 女性報告更高水平的學校聯結。

與本研究假設一致, 年齡對學校聯結與抑郁關系有調節作用。具體表現為, 隨著樣本平均年齡的增長, 學校聯結與抑郁的負相關強度減小。這表明, 學校聯結對抑郁的影響隨年齡增長而減弱。隨著年齡增加, 來自學校的壓力增強, 這可能削弱個體的學校聯結水平, 導致學校聯結對個體的抑郁保護作用降低(Henrich et al., 2005; Xu & Fang, 2021)。這與Rose等人(2022)的發現一致, Rose等人的研究表明學校聯結對心理健康的保護作用隨年齡增長而減弱。該結果一定程度上符合社會支持源一致理論, 當引發抑郁的壓力因素和減少抑郁的保護因素同源于學校時, 其保護作用將隨壓力的增強而減少。這可能因為, 學校聯結會促使學生不斷適應來自學校重要他人的期待, 當來自學校的壓力增強時, 高學校聯結個體更可能抑制表達由壓力引發的抑郁情緒, 這不僅無法降低抑郁水平, 甚至導致抑郁情緒的累積(Datu et?al., 2022)。然而, 本研究并沒有直接檢驗來自學校的壓力在學校聯結與抑郁關系中的作用, 未來需要更多研究對此問題做深入剖析。

與本研究的假設一致, 抑郁的測量工具顯著調節學校聯結與抑郁的關系。該結果表明, 不同測量工具測得的抑郁與學校聯結的相關程度不一致, 使用CDI量表測得的效應值最大, 使用OMDS量表測得的效應值最小。這可能因為, CDI測量的是兒童的悲傷、孤獨感、自我形象和社會適應(Sitarenios & Kovacs, 1999), 項目數較多, 較為全面, 是目前針對兒童青少年抑郁使用最廣泛的自評量表(柳之嘯 等, 2019)。而OMDS量表測量的是個體過去30天的抑郁情緒和抑郁行為(Orpinas, 1993), 項目數較少, 可能無法全面地衡量個體抑郁。本研究的結果和Fried (2017)的研究結果一致。Fried的研究發現采用不同抑郁量表所測的抑郁結果不盡相同。值得注意的是, 本研究發現學校聯結的測量工具不調節學校聯結與抑郁的關系。可能的原因是盡管學校聯結不同的測量工具在內容和項目數量上均存在差異, 但是它們都涵蓋了學校聯結的主要內容, 具有趨同性。因此, 學校聯結與抑郁的關系在不同學校聯結測量工具下的結果相近。

本研究發現研究數據屬性調節學校聯結與抑郁的關系, 具體而言, 與縱向數據相比, 橫斷數據下的兩者關系強度更大, 支持了本研究假設。隨時間推移, 影響抑郁的因素增多(Goering & Mrug, 2022), 這導致學校聯結與抑郁的相關減弱。這提示單一時間測量的橫斷數據容易夸大變量間的相關性, 未來應在不同時間點收集學校聯結與抑郁的數據, 以此把握兩者的動態趨勢和發展規律。

與本研究假設不一致的是, 文化不調節學校聯結與抑郁的關系。對此有兩種可能的解釋:一是無論在西方文化還是在中國文化下, 學校聯結均是抑郁的一個重要保護因素。雖然中國的集體主義文化強調人的互依性、西方的個人主義文化強調人的獨立性(黃梓航 等, 2018; Hofstede, 1980), 但它們對抑郁的總體效果是一致的。二是西方文化和中國文化的效應值有差異。然而, 當前元分析中基于中國文化的效應值較少(僅占15.27%), 效應值分布不均衡可能影響了調節效應的檢出。學校聯結與抑郁關系的文化差異還需更多跨文化研究來對此問題做深入剖析以驗證本研究結果的可靠性。

同時, 與本研究假設不一致, 發表年份不調節學校聯結與抑郁的關系。該結果與Allen等人(2018)的元分析結果一致。Allen等人通過元分析發現中學生的學校聯結與心理健康的關系不隨發表年份變化。這或許表明學校聯結與抑郁的關系強度不隨時代變遷和社會發展而變化。另一個可能的解釋是, 雖然隨時代發展, 來自學校的壓力增加(俞國良, 王浩, 2020), 學校聯結對個體抑郁的保護作用可能隨之減弱; 但與此同時, 一些心理健康的保護因素(例如. 積極的父母教養方式)也在隨著時代發展, 能更有效地緩解學校壓力(Sari & Sulistiyaningsih, 2023; Liu & Rahman, 2022), 這或許在一定程度上抵消了學校壓力對學校聯結與抑郁關系造成的影響。當然, 這一假設仍有待進一步檢驗。在納入的原始研究中, 報告數據收集年份的效應值太少, 這限制了本研究對時代指標的選取。值得注意的是, 僅采用論文發表年份作為時代的指標不僅過于簡單(辛自強 等, 2013), 而且會低估數據收集的時效性(Oliver & Hyde, 1993)。未來研究需要選取更多的指標(例如. 數據收集年份)進一步考察時代的影響。

4.3? 研究意義

本研究使用三水平元分析技術整合了國內外學校聯結與抑郁關系的量化研究, 探討了學校聯結與抑郁的關系及其調節變量。本研究的理論和實踐意義如下: 第一, 本研究發現年齡、性別調節學校聯結與抑郁的關系, 但發表年份和中西方文化類型不調節兩者的關系。該結果表明學校聯結對抑郁的保護作用受到個體特征的影響, 且在不同時代和文化下均具有一致性。這不僅為解釋現有研究結果間的不一致提供了思路, 而且提示了在運用學校聯結干預抑郁時, 應注意社會環境和個體的心理、生理特征。第二, 本研究發現, 研究數據屬性和抑郁測量工具會影響兩者關系強度。這提示在評估學校聯結與抑郁的關系時要考慮數據收集的時間間隔和抑郁量表的選擇。第三, 本研究不僅發現學校聯結與抑郁在主效應上存在中等程度的負相關, 同時在發表偏倚檢驗中剪補了55個學校聯結與抑郁的正相關。這提示了學校聯結對抑郁可能存在“雙刃劍”效應, 在運用學校聯結預防和干預抑郁時需要考慮不同情境。未來在促進學校聯結來預防和干預抑郁問題時, 不僅需要關注學校聯結程度的提高, 還需注意個體差異并降低來自學校的壓力, 以此更恰當地運用學校聯結來預防和干預個體抑郁。

4.4? 不足與展望

本研究可能存在以下不足之處, 有待未來研究進一步完善。第一, 本研究納入分析的大多數原始文獻采用自我報告法測量學校聯結和抑郁, 這可能會導致共同方法偏差; 并且, 被試自我報告的準確性可能會受到記憶效果、掩飾等因素的影響。因此, 為了有效減少共同方法偏差, 提高分析結果的可靠性, 未來可以結合自我報告、他人報告、生理測驗等工具開展進一步研究以驗證本研究的結果。第二, 學校聯結包含學校歸屬(school belonging)、對學校重要性的態度(attitudes about school importance)和社會隸屬(social af?liation)三個維度(Marraccini & Brier, 2017)。已有研究發現, 學校聯結的維度調節學校聯結與心理健康的關系(Rose et al., 2022), 學校聯結不同維度與抑郁關系的差異也可能是造成異質性的原因。但由于本研究納入分析的大多原始文獻只報告了學校聯結總分與抑郁的關系, 因此未能探討學校聯結的不同維度對抑郁的影響。未來研究可以關注不同維度的學校聯結與抑郁的關系, 更全面的探討學校聯結對抑郁的影響。第三, 已有研究表明兩者之間可能存在雙向影響的關系(Davis et al., 2019; Klinck et al., 2020)。本研究只能推論出學校聯結和抑郁存在相關關系, 無法揭示兩者關系的方向。因此未來可以使用交叉滯后分析對兩者關系的方向進行探討。第四, 已有研究發現, 種族(Eugene et al., 2021)、學生的希望感(Gerard & Booth, 2015)、學業志向(Gerard & Booth, 2015)可能調節二者關系, 但是本研究納入元分析的大部分文獻沒有報告研究對象的這些信息, 因此無法進行調節效應分析。未來元分析研究在考察學校聯結與抑郁的關系時可以進一步探討這些調節變量, 進而更好地歸納學校聯結影響抑郁的條件。

5? 結論

本研究通過三水平元分析技術發現, 學校聯結與抑郁存在顯著負相關, 學校聯結程度越高, 個體抑郁水平越低。學校聯結與抑郁的關系受到性別的調節, 相比男性, 女性的抑郁水平受學校聯結的影響更大。學校聯結與抑郁的關系受到年齡的調節, 學校聯結與抑郁的負相關隨年齡的增長而減小。抑郁測量工具和研究數據屬性均能調節學校聯結與抑郁的關系; 發表年份、文化類型、學校聯結測量工具對學校聯結與抑郁關系的調節不顯著。

參考文獻

*元分析用到的參考文獻

*阿依孜巴·艾拜都拉. (2020). 中學生同伴依戀對抑郁的影響: 自尊和學校歸屬感的多重中介作用 (碩士學位論文). 新疆師范大學, 烏魯木齊.

陳春花, 蘇濤, 王杏珊. (2016). 中國情境下變革型領導與績效關系的Meta分析. 管理學報, 13(8), 1174?1183.

*陳小莉. (2019). 高中生學校歸屬感與抑郁, 焦慮的關系研究——心理彈性的中介作用 (碩士學位論文). 華中師范大學, 武漢.

*杜漸, 楊秋莉, 杜麗紅, 楊鄰, 張杰, 孔軍輝. (2012). 中醫學生學校歸屬感與心理健康的關系. 中醫教育, 31(4), 15?18.

*方敏. (2020). 高年級小學生綜合活力對抑郁情緒的影響: 學校歸屬感的中介作用 (碩士學位論文). 湖南師范大學, 長沙.

黃梓航, 敬一鳴, 喻豐, 古若雷, 周欣悅, 張建新, 蔡華儉. (2018). 個人主義上升, 集體主義式微? ——全球文化變遷與民眾心理變化. 心理科學進展, 26(11), 2068?2080.

柳之嘯, 李京, 王玉, 苗淼, 鐘杰. (2019). 中文版兒童抑郁量表的結構驗證及測量等值. 中國臨床心理學雜志, 27(6), 1172?1176.

*孫亞東. (2022). 農村青少年網絡成癮類別及其與抑郁和問題行為的關系: 學校聯結的中介作用 (碩士學位論文). 西南大學, 重慶.

*覃小瓊. (2020). 同伴侵害與中學生抑郁: 父母支持和聯結的鏈式中介作用 (碩士學位論文). 皖南醫學院, 蕪湖.

*覃小瓊, 李秀. (2022). 網絡受欺負與青少年抑郁: 孤獨感與學校聯結的作用. 教育生物學雜志, 10(6), 473?478.

*溫麗影, 朱麗君, 劉傳, 蘇姍姍, 金岳龍, 常微微. (2023). 安徽省某醫學院校在校大學生專業認同和學校歸屬感與心理健康的關系. 沈陽醫學院學報, 25(1), 58?64.

辛自強, 張梅, 何琳. (2012). 大學生心理健康變遷的橫斷歷史研究. 心理學報, 44(5), 664?679.

*邢強, 梁俏, 李佳佳, 唐輝, 莫綺云. (2023). 學業鼓勵對初中生抑郁的影響: 學校聯結的中介作用和堅毅的調節作用. 廣東第二師范學院學報, 43(3), 85?97.

殷顥文, 賈林祥. (2014). 學校聯結的研究現狀與發展趨勢. 心理科學, 37(5), 1180?1184.

俞國良, 王浩. (2020). 文化潮流與社會轉型: 影響我國青少年心理健康狀況的重要因素以及現實策略. 西南民族大學學報(人文社科版), 41(9), 213?219.

張建平, 秦傳燕, 劉善仕. (2020). 尋求反饋能改善績效嗎? ——反饋尋求行為與個體績效關系的元分析. 心理科學進展, 28(4), 549?565.

*趙姒. (2022). 情感虐待對留守高中生抑郁的影響: 冗思的中介與學校聯結的調節作用 (碩士學位論文). 信陽師范學院.

*趙子薇. (2022). 父母心理攻擊對初中生抑郁情緒的影響: 自尊和學校聯結的作用 (碩士學位論文). 山西大學, 太原.

周文潔. (2013). 高中生情緒表達性的個體差異研究. 中國民康醫學, 25(19), 67?69 + 86.

Allen, K., Kern, M. L., Vella-Brodrick, D., Hattie, J., & Waters, L. (2018). What schools need to know about fostering school belonging: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 30, 1?34.

*Anderman, E. M. (2002). School effects on psychological outcomes during adolescence. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(4), 795?809.

*Arango, A., Clark, M., & King, C. A. (2022). Predicting the severity of peer victimization and bullying perpetration among youth with interpersonal problems: A 6-month prospective study. Journal of Adolescence, 94(1), 57?68.

*Arango, A., Cole-Lewis, Y., Lindsay, R., Yeguez, C. E., Clark, M., & King, C. (2019). The protective role of connectedness on depression and suicidal ideation among bully victimized youth. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 48(5), 728?739.

Assink, M., & Wibbelink, C. J. (2016). Fitting three-level meta-analytic models in R: A step-by-step tutorial. The Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 12(3), 154?174.

Bakan, D. (1966). The duality of human existence. Chicago, IL: Rand McNally.

Barbee, A. P., Cunningham, M. R., Winstead, B. A., Derlega, V. J., Gulley, M. R., Yankeelov, P. A., & Drue, P. B. (1993). Effects of gender role expectations on the social support process. Journal of Social Issues, 49(3), 175?190.

*Baker, A. C., Wallander, J. L., Elliott, M. N., & Schuster, M. A. (2023). Non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents: A structural model with socioecological connectedness, bullying victimization, and depression. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 54(4), 1190?1208.

*Bakhtiari, F., Boyle, A. E., & Benner, A. D. (2020). Pathways linking school-based ethnic discrimination to Latino/a adolescents marijuana approval and use. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 22, 1273?1280.

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497? 529.

*Bouchard, M., Denault, A. S., & Guay, F. (2022). Extracurricular activities and adjustment among students at disadvantaged high schools: The mediating role of peer relatedness and school belonging. Journal of Adolescence, 95(3), 1?15.

*Burns, J. R., & Rapee, R. M. (2019). School‐based assessment of mental health risk in children: The preliminary development of the Child RADAR. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 24(1), 66?75.

Card, N. A. (Ed). (2012). Applied meta-analysis for social science research. New York: Guilford Press.

Chen, X., Chang, L., & He, Y. (2003). The peer group as a context: Mediating and moderating effects on relations between academic achievement and social functioning in Chinese children. Child Development, 74(3), 710?727.

Cheung, M. W.-L. (2014). Modeling dependent effect sizes with three-level meta-analyses: A structural equation modeling approach. Psychological Methods, 19(2), 211? 229.

*Choi, J. K., Ryu, J. H., & Yang, Z. (2021). Validation of the engagement, perseverance, optimism, connectedness, and happiness measure in adolescents from multistressed families: Using first-and second-order confirmatory factor analysis models. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 39(4), 494?507.

*Choi, M. J., Hong, J. S., Travis Jr, R., & Kim, J. (2023). Effects of school environment on depression among Black and White adolescents. Journal of Community Psychology, 51(3), 1181?1200.

Cohen, J. (1992). Quantitative methods in psychology: A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155?159.

*Cole-Lewis, Y. C., Gipson, P. Y., Opperman, K. J., Arango, A., & King, C. A. (2016). Protective role of religious involvement against depression and suicidal ideation among youth with interpersonal problems. Journal of Religion and Health, 55, 1172?1188.

Cooper, H., Hedges, L. V., & Valentine, J. C. (2019). The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis. Russell Sage Foundation.

*Cupito, A. M., Stein, G. L., & Gonzalez, L. M. (2015). Familial cultural values, depressive symptoms, school belonging and grades in Latino adolescents: Does gender matter? Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 1638? 1649.

*Daley, S. C. (2019). School connectedness and mental health in college students. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Miami University, Oxford.

*Dansby Olufowote, R. A., Soloski, K. L., Gonzalez- Caste?eda, N., & Hayes, N. D. (2020). An accelerated latent class growth curve analysis of adolescent bonds and trajectories of depressive symptoms. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29, 292?306.

*Datu, J. A. D., Mateo, N. J., & Natale, S. (2023). The mental health benefits of kindness-oriented schools: School kindness is associated with increased belongingness and well-being in Filipino high school students. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 54(4), 1075?1084.

*Davis, J. P., Merrin, G. J., Ingram, K. M., Espelage, D. L., Valido, A., & El Sheikh, A. J. (2019). Examining pathways between bully victimization, depression, & school belonging among early adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28, 2365?2378.

Dodell-Feder, D., & Tamir, D. I. (2018). Fiction reading has a small positive impact on social cognition: A meta- analysis. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 147(11), 1713?1727.

Duval, S., & Tweedie, R. (2000). Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot?based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics, 56(2), 455? 463.

*Ernestus, S. M., Prelow, H. M., Ramrattan, M. E., & Wilson, S. A. (2014). Self-system processes as a mediator of school connectedness and depressive symptomatology in African American and European American adolescents. School Mental Health, 6, 175?183.

*Eugene, D. R. (2021). Connectedness to family, school, and neighborhood and adolescents internalizing symptoms. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(23), 12602.

*Eugene, D. R., Crutchfield, J., & Robinson, E. D. (2021). An examination of peer victimization and internalizing problems through a racial equity lens: Does school connectedness matter? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(3), 1085.

*Fernandez, A., Loukas, A., Golaszewski, N. M., Batanova, M., & Pasch, K. E. (2019). Adolescent adjustment problems mediate the association between racial discrimination and school connectedness. Journal of School Health, 89(12), 945?952.

*Forbes, M. K., Fitzpatrick, S., Magson, N. R., & Rapee, R. M. (2019). Depression, anxiety, and peer victimization: Bidirectional relationships and associated outcomes transitioning from childhood to adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48, 692?702.

Fox, J. (2019). Regression diagnostics: An introduction. Sage publications.

Franco, A., Malhotra, N., & Simonovits, G. (2014). Publication bias in the social sciences: Unlocking the file drawer. Science, 345(6203), 1502?1505.

Fried, E. I. (2017). The 52 symptoms of major depression: Lack of content overlap among seven common depression scales. Journal of Affective Disorders, 208, 191?197.

Gao, S., Yu, D., Assink, M., Chan, K. L., Zhang, L., & Meng, X. (2023). The association between child maltreatment and pathological narcissism: A three-level meta-analytic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 25(1). https://doi.org/ 10.1177/15248380221147559

*Gerard, J. M., & Booth, M. Z. (2015). Family and school influences on adolescents' adjustment: The moderating role of youth hopefulness and aspirations for the future. Journal of Adolescence, 44, 1?16.

*Gilman, R., & Anderman, E. M. (2006). The relationship between relative levels of motivation and intrapersonal, interpersonal, and academic functioning among older adolescents. Journal of School Psychology, 44(5), 375? 391.

*Goering, M., & Mrug, S. (2022). The distinct roles of biological and perceived pubertal timing in delinquency and depressive symptoms from adolescence to adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 51(11), 2092?2113.

*Gonzalez, L. M., Stein, G. L., Kiang, L., & Cupito, A. M. (2014). The impact of discrimination and support on developmental competencies in Latino adolescents. Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 2(2), 79?91.

Goodenow, C. (1993). The psychological sense of school membership among adolescents: Scale development and educational correlates. Psychology in the Schools, 30, 79?90.

Goodenow, C., & Grady, K. E. (1993). The relationship of school belonging and friends values to academic motivation among urban adolescent students. The Journal of Experimental Education, 62, 60?71.

*Gummadam, P., Pittman, L. D., & Ioffe, M. (2016). School belonging, ethnic identity, and psychological adjustment among ethnic minority college students. The Journal of Experimental Education, 84(2), 289?306.

Harrer, M., Cuijpers, P., Furukawa, T.A., & Ebert, D.D. (2021). Doing meta-analysis with R: A hands-on guide (1st ed.). Chapman and Hall/CRC.

*Hatchel, T., Espelage, D. L., & Huang, Y. (2018). Sexual harassment victimization, school belonging, and depressive symptoms among LGBTQ adolescents: Temporal insights. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 88(4), 422?430.

*Hayre, R. S., Sierra Hernandez, C., Goulter, N., & Moretti, M. M. (2023, March). Attachment & school connectedness: Associations with substance use, depression, & suicidality among at-risk adolescents. Child & Youth Care Forum, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-023-09743-y

*He, G. H., Strodl, E., Chen, W. Q., Liu, F., Hayixibayi, A., & Hou, X. Y. (2019). Interpersonal conflict, school connectedness and depressive symptoms in Chinese adolescents: Moderation effect of gender and grade level. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(12), 2182.

Hedges, L. V., & Vevea, J. L. (1998). Fixed- and random- effects models in meta-analysis. Psychological Methods, 3, 486?504.

Henrich, C. C., Brookmeyer, K. A., & Shahar, G. (2005). Weapon violence in adolescence: Parent and school connectedness as protective factors. Journal of Adolescent Health, 37(4), 306?312.

Hirschi, T. (1996). Theory without ideas: Reply to Akers. Criminology, 34, 249.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Motivation, leadership, and organization: Do American theories apply abroad? Organizational Dynamics, 9(1), 42?63.

Hofstede, G. (1984). Cultural dimensions in management and planning. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 1, 81?99.

*Hsieh, Y. P., Lu, W. H., & Yen, C. F. (2019). Psychosocial determinants of insomnia in adolescents: Roles of mental health, behavioral health, and social environment. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 13, 848.

*Jacobson, K. C., & Rowe, D. C. (1999). Genetic and environmental influences on the relationships between family connectedness, school connectedness, and adolescent depressed mood: Sex differences. Developmental Psychology, 35(4), 926.

*Jin, L., Hao, Z., Huang, J., Akram, H. R., Saeed, M. F., & Ma, H. (2021). Depression and anxiety symptoms are associated with problematic smartphone use under the COVID-19 epidemic: The mediation models. Children and Youth Services Review, 121, 105875.

*Joyce, H. D., & Early, T. J. (2014). The impact of school connectedness and teacher support on depressive symptoms in adolescents: A multilevel analysis. Children and Youth Services Review, 39, 101?107.

*Kaminski, J. W., Puddy, R. W., Hall, D. M., Cashman, S. Y., Crosby, A. E., & Ortega, L. A. (2010). The relative influence of different domains of social connectedness on self-directed violence in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39, 460?473.

*Kelly, A. B., OFlaherty, M., Toumbourou, J. W., Homel, R., Patton, G. C., White, A., & Williams, J. (2012). The influence of families on early adolescent school connectedness: Evidence that this association varies with adolescent involvement in peer drinking networks. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40, 437?447.

Kepes, S., & Thomas, M. A. (2018). Assessing the robustness of meta-analytic results in information systems: Publication bias and outliers. European Journal of Information Systems, 27(9), 90?123.

*Kia-Keating, M., & Ellis, B. H. (2007). Belonging and connection to school in resettlement: Young refugees, school belonging, and psychosocial adjustment. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 12(1), 29?43.

Kieling, C., Adewuya, A., Fisher, H. L., Karmacharya, R., Kohrt, B. A., Swartz, J. R., & Mondelli, V. (2019). Identifying depression early in adolescence. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 3(4), 211?213.

*Klinck, M., Vannucci, A., & Ohannessian, C. M. (2020). Bidirectional relationships between school connectedness and internalizing symptoms during early adolescence. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 40(9), 1336?1368.

Korpershoek, H., Canrinus, E. T., Fokkens-Bruinsma, M., & de Boer, H. (2020). The relationships between school belonging and students motivational, social-emotional, behavioural, and academic outcomes in secondary education: A meta-analytic review. Research Papers in Education, 35(6), 641?680.

*Kuo, F. W., & Yang, S. C. (2019). In-group comparison is painful but meaningful: The moderator of classroom ethnic composition and the mediators of self-esteem and school belonging for upward comparisons. The Journal of Social Psychology, 159(5), 531?545.

*Lardier, D. T., Opara, I., Bergeson, C., Herrera, A., Garci- Reid, P., & Reid, R. J. (2019). A study of psychological sense of community as a mediator between supportive social systems, school belongingness, and outcome behaviors among urban high school students of color. Journal of Community Psychology, 47(5), 1131?1150.

*LaRusso, M. D., Romer, D., & Selman, R. L. (2008). Teachers as builders of respectful school climates: Implications for adolescent drug use norms and depressive symptoms in high school. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37, 386?398.

*L?tsch, A. (2018). The interplay of emotional instability and socio-environmental aspects of schools during adolescence. European Journal of Educational Research, 7(2), 281?293.

Leary, M. R. (2005). Sociometer theory and the pursuit of relational value: Getting to the root of self-esteem. European Review of Social Psychology, 16(1), 75?111.

Lebow, J. L. (2005). Family therapy at the beginning of the twenty-first century. In J. Lebow (Ed.), Handbook of Clinical Family Therapy (pp. 1?14). Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

*Lee, J., Chun, J., Kim, J., Lee, J., & Lee, S. (2021). A social-ecological approach to understanding the relationship between cyberbullying victimization and suicidal ideation in South Korean adolescents: The moderating effect of school connectedness. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(20), 10623.

Libbey, H. P. (2004). Measuring student relationships to school: Attachment, bonding, connectedness, and engagement. Journal of School Health, 74, 274?283.

Lipsey, M. W., & Wilson, D. B. (2001). Practical meta-analysis. SAGE publications.

Liu, C., & Rahman, M. N. A. (2022). Relationships between parenting style and sibling conflicts: A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 936253.

*Liu, S., Wu, W., Zou, H., Chen, Y., Xu, L., Zhang, W., Yu, C & Zhen, S. (2023). Cyber victimization and non-suicidal self-injury among Chinese adolescents: The effect of depression and school connectedness. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1091959.

*Loukas, A., & Pasch, K. E. (2013). Does school connectedness buffer the impact of peer victimization on early adolescents subsequent adjustment problems? The Journal of Early Adolescence, 33(2), 245?266.

*Loukas, A., Suzuki, R., & Horton, K. D. (2006). Examining school connectedness as a mediator of school climate effects. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 16(3), 491? 502.

*Marksteiner, T., Janke, S., & Dickh?user, O. (2019). Effects of a brief psychological intervention on students' sense of belonging and educational outcomes: The role of students' migration and educational background. Journal of School Psychology, 75, 41?57.

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (2014). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. In college student development and academic life (pp. 264?293). Routledge.

Marraccini, M. E., & Brier, Z. M. (2017). School connectedness and suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A systematic meta-analysis. School Psychology Quarterly, 32(1), 5?21.

*Maurizi, L. K., Ceballo, R., Epstein‐Ngo, Q., & Cortina, K. S. (2013). Does neighborhood belonging matter? Examining school and neighborhood belonging as protective factors for Latino adolescents. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 83(2?3), 323?334.

*Mcgraw, K., Moore, S., Fuller, A., & Bates, G. (2008). Family, peer and school connectedness in final year secondary school students. Australian Psychologist, 43(1), 27?37.

*McLaren, S., Schurmann, J., & Jenkins, M. (2015). The relationships between sense of belonging to a community GLB youth group; school, teacher, and peer connectedness; and depressive symptoms: Testing of a path model. Journal of Homosexuality, 62(12), 1688?1702.

*McMahon, S. D., Parnes, A. L., Keys, C. B., & Viola, J. J. (2008). School belonging among low‐income urban youth with disabilities: Testing a theoretical model. Psychology in the Schools, 45(5), 387?401.

*Midgett, A., & Doumas, D. M. (2019). The impact of a brief bullying bystander intervention on depressive symptoms. Journal of Counseling & Development, 97(3), 270?280.

*Millings, A., Buck, R., Montgomery, A., Spears, M., & Stallard, P. (2012). School connectedness, peer attachment, and self-esteem as predictors of adolescent depression. Journal of Adolescence, 35(4), 1061?1067.

*Mrug, S., King, V., & Windle, M. (2016). Brief report: Explaining differences in depressive symptoms between African American and European American adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 46, 25?29.

National Institutes of Health. (2014). Study quality assessment tools. Retrieved from: https://www.nhlbi.nih. gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools

Oelsner, J., Lippold, M. A., & Greenberg, M. T. (2011). Factors influencing the development of school bonding among middle school students. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 31(3), 463?487.

Oliver, M. B., & Hyde, J. S. (1993). Gender differences in sexuality: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin,?114(1), 29?51.

Orpinas, P. (1993). Modified depression scale. Houston, TX: University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J.E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. International Journal of Surgery, 74(9), 790?799.

*Pang, Y. C. (2015). The relationship between perceived discrimination, economic pressure, depressive symptoms, and educational attainment of ethnic minority emerging adults: The moderating role of school connectedness during adolescence (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Iowa State University, Ames.

Park, J., Kitayama, S., Karasawa, M., Curhan, K., Markus, H. R., Kawakami, N., ...

*Ream, G. L. (2006). Reciprocal effects between the perceived environment and heterosexual intercourse among adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35, 768?782.

Reed, W. R., Florax, R. J. G. M., & Poot, J. (2015). A monte carlo analysis of alternative meta-analysis estimators in the presence of publication bias. Retrieved from http:// www.economics-ejournal.org/economics/discussionpapers/2015-9

Resnick, M. D., Bearman, P. S., Blum, R. W., Bauman, K. E., Harris, K. M., Jones, J., ... Udry, J. R. (1997). Protecting adolescents from harm: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 278(10), 823?832.

Rodgers, M. A., & Pustejovsky, J. E. (2021). Evaluating meta-analytic methods to detect selective reporting in the presence of dependent effect sizes. Psychological Methods, 26(2), 141?160.

Rose, I. D., Lesesne, C. A., Sun, J., Johns, M. M., Zhang, X., & Hertz, M. (2022). The relationship of school connectedness to adolescents engagement in co-occurring health risks: A meta-analytic review. The Journal of School Nursing, 10598405221096802

*Ross, A. G., Shochet, I. M., & Bellair, R. (2010). The role of social skills and school connectedness in preadolescent depressive symptoms. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 39(2), 269?275.

Rueger, S. Y., Malecki, C. K., Pyun, Y., Aycock, C., & Coyle, S. (2016). A meta-analytic review of the association between perceived social support and depression in childhood and adolescence. Psychological Bulletin, 142(10), 1017.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Publications.

Sandler, I. (2001). Quality and ecology of adversity as common mechanisms of risk and resilience. American Journal of Community Psychology, 29(1), 19?61.

Sari, U. K., & Sulistiyaningsih, R. (2023). Parenting style to reduce academic stress in early childhood during the new normal. Indigenous: Jurnal Ilmiah Psikologi, 8(1), 82?93.

Sitarenios, G., & Kovacs, M. (1999). Use of the children's depression inventory. In M. E. Maruish (Ed.), The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcome assessment (pp. 267?298). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

*Shochet, I. M., Dadds, M. R., Ham, D., & Montague, R. (2006). School connectedness is an underemphasized parameter in adolescent mental health: Results of a community prediction study. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 35(2), 170?179.

*Shochet, I. M., Homel, R., Cockshaw, W. D., & Montgomery, D. T. (2008). How do school connectedness and attachment to parents interrelate in predicting adolescent depressive symptoms? Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 37(3), 676?681.

*Shochet, I. M., Smith, C. L., Furlong, M. J., & Homel, R. (2011). A prospective study investigating the impact of school belonging factors on negative affect in adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 40(4), 586?595.

Sterne, J. A., & Harbord, R. M. (2004). Funnel plots in meta-analysis. The Stata Journal, 4(2), 127?141.

*Sun, R. C., & Hui, E. K. (2007). Psychosocial factors contributing to adolescent suicidal ideation. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36, 775?786.

*Tang, T. C., Ko, C. H., Yen, J. Y., Lin, H. C., Liu, S. C., Huang, C. F., & Yen, C. F. (2009). Suicide and its association with individual, family, peer, and school factors in an adolescent population in southern Taiwan. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 39(1), 91?102.

Thapar, A., Collishaw, S., Pine, D. S., & Thapar, A. K. (2012). Depression in adolescence. The Lancet, 379(9820), 1056?1067.

*Thomson, K. C., Schonert-Reichl, K. A., & Oberle, E. (2015). Optimism in early adolescence: Relations to individual characteristics and ecological assets in families, schools, and neighborhoods. Journal of Happiness Studies, 16, 889?913.

*Thornton, B. E. (2020). The impact of internalized, anticipated, and structural stigma on psychological and school outcomes for high school students with learning disabilities: A pilot study. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of California, Los Angeles.

*Truong, N. L., & Zongrone, A. D. (2022). The role of GSA participation, victimization based on sexual orientation, and race on psychosocial well‐being among LGBTQ secondary school students. Psychology in the Schools, 59(1), 181?207.

Vannucci, A., & McCauley Ohannessian, C. (2018). Self- competence and depressive symptom trajectories during adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 46, 1089?1109.

Viechtbauer, W. (2010). Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. Journal of Statistical Software, 36(3), 1?48.

Viechtbauer, W., & Cheung, M. W. L. (2010). Outlier and influence diagnostics for meta‐analysis. Research Synthesis Methods, 1(2), 112?125.

World Health Organization. (2023). Depression. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ depression.

*Wright, M. F., & Wachs, S. (2019). Adolescents psychological consequences and cyber victimization: The moderation of school-belongingness and ethnicity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(14), 2493.

Wright, M. O. D., & Masten, A. S. (2005). Resilience processes in development: Fostering positive adaptation in the context of adversity. In S. Goldstein & R. B. Brooks (Eds.), Handbook of resilience in children (pp. 17?37). Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

*Wright, S. (2017). How does coping impact stress, anxiety, and the academic and psychosocial functioning of homeless students? (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Arizona.

Xu, Z. Z., & Fang, C. C. (2021). The relationship between school bullying and subjective well-being: The mediating effect of school belonging. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 725542.

Yang, L., Zheng, Y., & Chen, R. (2021). Who has a cushion? The interactive effect of social exclusion and gender on fixed savings. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 55(4), 1398? 1415.

*Yang, Y., Ma, X., Kelifa, M. O., Li, X., Chen, Z., & Wang, P. (2022). The relationship between childhood abuse and depression among adolescents: The mediating role of school connectedness and psychological resilience. Child Abuse & Neglect, 131, 105760.

*Zhai, B., Li, D., Li, X., Liu, Y., Zhang, J., Sun, W., & Wang, Y. (2020). Perceived school climate and problematic internet use among adolescents: Mediating roles of school belonging and depressive symptoms. Addictive Behaviors, 110, 106501.

*Zhang, M. X., Mou, N. L., Tong, K. K., & Wu, A. M. (2018). Investigation of the effects of purpose in life, grit, gratitude, and school belonging on mental distress among Chinese emerging adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(10), 2147.

*Zhang, Z., Wang, Y., & Zhao, J. (2022). Longitudinal relationships between interparental conflict and adolescent depression: Moderating effects of school connectedness. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 1?10.

*Zhao, Y., & Zhao, G. (2015). Emotion regulation and depressive symptoms: Examining the mediation effects of school connectedness in Chinese late adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 40, 14?23.

*Zhou, X., Min, C. J., Kim, A. Y., Lee, R. M., & Wang, C. (2022). Do cross-race friendships with majority and minority peers protect against the effects of discrimination on school belonging and depressive symptoms? International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 91, 242?251.

The relationship between school connectedness and depression:A three-level meta-analytic review

MENG Xianxin1, CHEN Yijing1, WANG Xinyi1, YUAN Jiajin2, YU Delin1

(1 School of Psychology, Fujian Normal University, Fuzhou 350117, China)(2 Sichuan Key Laboratory of Psychology and Behavior of Discipline Inspection and Supervision, Institute of Brain and Psychological Sciences, Sichuan Normal University, Chengdu 610066, China)

Abstract: Existing studies on the relationship between school connectedness and depression have produced inconsistent results. To clarify the extent to which school connectedness is associated with depression, and whether these associations differed according to the study or sample characteristics, a three-level meta-analysis of 87 included studies (206 effect sizes) was conducted. The results showed that there was a significant negative correlation between school connectedness and depression but only to a medium extent (r = ?0.39, df = 205, p < 0.001). Additionally, the relationship between school connectedness and depression was found to be moderated by the percentage of female students, mean age of participants, measurement of depression, and data characteristics. No significant moderating effects were found for the measurement of school connectedness, culture, or publication year. School connectedness is a protective factor for depression. Interventions targeting depression should be aware of school connectedness.

Keywords: school connectedness, depression, three-level meta-analysis, social control theory, sociometer theory, self-determination theory

附錄C? 數據分析中使用到的計算公式

使用Hedges和Vevea (1998)提出的公式將相關系數r轉換為Fisher's z。

其中r是皮爾遜積差相關系數, zr是r的Fisher變換后的值。

主效應的標準誤是其方差的平方根。

將zr轉換回r。

其中e是指數函數, r是皮爾遜積差相關系數, zr是r的費舍爾變換。

使用三水平元分析模型估計學校聯結和抑郁之間的關系的主效應大小。

Level 1 model: yij = λij + eij

Level 2 model: λij = κj + u (2)ij

Level 3 model: κj = β0 + u (3)j??? (Eq. 7)

其中, yij代表第j項研究中的一個獨特的效應大小; λij是“真實”的效應大小; eij是第j項研究中第i個效應大小的已知抽樣誤差。κj是第j項研究的平均效應; β0是平均群體效應, Var (u (2)ij) =和Var (u (3)ij) =分別是研究特定的2級和3級異質性。

與兩水平元分析模型類似, 上述等式通常被合并為:

yij = β0 + u (2)ij + u (3)j + eij????? (Eq. 8)

使用混合效應模型來研究(潛在的)調節變量對學校聯結和抑郁之間關系的影響。有一個協變量的混合效應模型如下:

yij = β0 + β1Xij + u (2)ij + u (3)j + eij ????? (Eq. 9)

其中X是協變量, 其他項的解釋與Eq. 8類似, 只是和現在是控制協變量后的二水平和三水平殘留異質性。