加強“將健康融入所有政策”的實施:基于現實主義的解釋性案例研究

Ketan Shankardass Emilie Renahy Carles Muntaner,3,4 Patricia O’Campo,3

1. 威爾弗里德·勞雷爾大學心理學系 加拿大滑鐵盧 N2L 3C5 2. 圣米高醫院都市健康研究中心 加拿大多倫多 M5B 1W8 3. 多倫多大學達拉拉納公共衛生學院 加拿大多倫多 M5S 2J7 4. 多倫多大學布隆伯格護理學院 加拿大多倫多 M5S 2J7

?

·理論探討·

加強“將健康融入所有政策”的實施:基于現實主義的解釋性案例研究

Ketan Shankardass1,2,3Emilie Renahy2Carles Muntaner2,3,4Patricia O’Campo2,3

1. 威爾弗里德·勞雷爾大學心理學系 加拿大滑鐵盧 N2L 3C5 2. 圣米高醫院都市健康研究中心 加拿大多倫多 M5B 1W8 3. 多倫多大學達拉拉納公共衛生學院 加拿大多倫多 M5S 2J7 4. 多倫多大學布隆伯格護理學院 加拿大多倫多 M5S 2J7

目前,世界各國普遍采取跨部門行動解決健康的宏觀社會和經濟決定因素。“將健康融入所有政策(HiAP)”是各國采取跨部門行動的策略之一,它以廣義的健康決定因素而非單純的衛生服務為目標,在決策過程中系統解決健康問題。近幾十年來出現了很多關于HiAP的案例,但這些案例成功或失敗的原因并未得到系統的研究,這就導致以證據為基礎的有關促進或阻礙HiAP策略實施的相關因素的研究較少。本文基于現實主義視角,采用解釋性案例研究,分析了不同地區HiAP策略的實施情況。本研究在提出概念性框架的基礎上,分析了與HiAP可持續實施有關的背景、社會機制及結果,并利用相關文獻以及從關鍵知情人訪談中得到的證據,尋找相關的模式和主題對現象加以解釋。最后,通過對瑞典和加拿大魁北克實施衛生影響力評估的情況進行比較,揭示了HiAP成功實施的經驗。此方法能夠幫助研究者對某一地區內成功實施HiAP的社會機制和背景因素的大量證據信息加以審核并做三角測量,還可用于分析其他形式的部門間行動,以減少不同背景、不同地區之間的衛生不公平性現象。

衛生政策; 執行; 健康促進; 公平性; 決定因素; 社會決定因素; 社會流行病學

1 引言

1.1 “將健康融入所有政策”的定義

為了縮小全球范圍內的衛生不公平現象[1-5],不僅要提高衛生服務的質量和可及性[4, 6-15],而且要解決健康的宏觀社會和經濟決定因素。“將健康融入所有政策”(Health in All Policies,HiAP)要求政府各部門(如社會服務、住房、交通、教育、就業、消費者保護與環境)[4, 16-25]、私人部門和民間團體開展協同合作以解決復雜的衛生問題[4,14,26-34]。

與其他領域的跨部門行動相似,HiAP依靠各機構結構及其相關關系,協助決策者在政策的制定、執行和評估過程中關注健康及其公平性,從而取得更加有益的健康結果。[35]而HiAP與其他政策的區別在于,政府決策的過程是以廣義的健康問題社會決定因素為目標,而不僅僅局限于衛生服務。

與在某一地區實施一種單一的干預策略不同,HiAP通常是在一個更廣范圍的背景下實施一整套廣義的干預策略。例如,瑞典2002年公共衛生目標法案即是一項HiAP策略,其為實現全人群的健康公平性創造必需的社會條件[36],涉及11個健康問題的社會決定因素,涵蓋了國家級、地區級和地方級政府的31個政策領域。

1.2 有必要針對HiAP開展系統化研究以揭示成功的實踐經驗

2013年關于HiAP的赫爾辛基宣言強調,HiAP的實施越來越高效[37],這表明對政策實施本身開展研究的重要性已經超越了對政策結果的研究。考慮到不同地區以及不同政府層級及其參與者所采取的措施不同,HiAP的具體實踐行為也比較復雜。政府需要制定解決跨部門權力不均衡問題的制度化策略,如領導力、指令、激勵機制、預算承諾等,并將其納入政府議程從而找到綜合性的解決措施。[35]事實上,如果政府不能持續開展某一個HiAP模式,而是經常變化,將會打擊HiAP規劃和執行者的積極性。[38]

然而,目前關于政府應該如何制定成功的跨部門行動策略[39-40]和對跨部門行動策略進行分析的文獻很少,而這對于HiAP的實施來說是至關重要的[14]。全球范圍內的HiAP案例已經達數十個[41-43],盡管有研究已經對某些地區的HiAP策略進行了描述和比較,但并未闡述這些HiAP戰略如何以及為何能夠發揮作用[41,44-46]。一個國家的社會機制通常會促進或阻礙不同區域內HiAP的執行,但相關的研究證據卻很少。

1.3 基于現實主義視角,采用解釋性案例研究闡述HiAP的社會機制

本文基于現實主義視角,采用解釋性案例研究以更好的理解HiAP。現實主義認為現象是復雜的,但可以將影響HiAP實施因素理論化,通過案例研究來揭示HiAP如何以及為何能夠發揮作用的相關社會機制,從而對現象加以解釋。

本文的社會機制(以下簡稱“機制”)是指具有交互性但通常會隱藏起來的進程,其在HiAP的實施過程中制造因果鏈,并涉及兩個以上政治、文化或經濟領域的參與者。[47-48]其他有關社會機制的說法則更傾向于廣義的“生成機制(generative mechanisms)”,本文所關注的是植根于社會領域的機制,從而可以為HiAP實施提供強有力的解釋(如種族隔離和種族歧視的社會進程可以為不同社會背景下衛生的種族不平等提供解釋)。[49]

分析HiAP的實施情況充滿挑戰,HiAP的概念還不夠清晰,導致一個區域內可能并不是單一機制發揮作用。此外,一個HiAP可能會生成一個或多個計劃或項目,導致實施的時間很漫長。因此,一個地區內可能會出現多個相關機制,而這些機制的實施時間會達數年之久。最后,機制本身可能還涉及一系列合作伙伴的行動,包括政府部門內部、部門間以及私人部門和民間團體。此外,這些合作者還可能是在不同政府層級上參與機制的運行。

實際上,我們所采用的現實主義方法,是指一系列可以用于多個學科的研究方法,以揭示不易于被感官理解的深層次機制。[50-54]本文將機制概化為一種可以被觸發的裝置,并分析其與HiAP實施情況及結果(如HiAP的可接受性、可行性或可持續性)的關系。Pawson等人將其定義為“背景—機制—結果模式(以下簡稱CMOs)”。[52]通過此方法,我們將更好的理解不同地區內各部門是如何以及為何要開展合作來處理衛生公平效果和問題,了解能使HiAP有效實施的方法、不同背景下的結果及各自的原因。

目前,尚未有充分且嚴謹的研究方法來分析不同政府層級(國家、地區和市)執行宏觀社會衛生干預措施的相關機制—背景證據[55-56],這是HiAP系統化研究的最大障礙。解釋性(或因果性)案例研究通過特定的案例,對事物背后的因果關系進行分析和解釋。[57]案例研究一直被認為缺乏嚴謹性,因此其主要用于觀察性和描述性研究。[44]然而,最近也有研究表明了案例研究的正確性和有效性(包括內部有效性和外部有效性)以及用于解答準實驗研究問題的可靠性。[58]

1.4 解釋性案例研究的作用

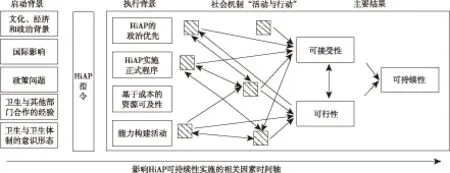

本研究采用解釋性案例研究以檢驗HiAP在全球范圍內的實施情況以及有關成功實踐經驗的理論構建。基于研究團隊在之前所做的現實主義研究,本文提出一個與HiAP的啟動和實施有關的框架[43],為利用CMOs進行分析奠定基礎(圖1)。此框架呈現的是一種中型理論[59],對CMOs系統化,以解釋案例研究中有關HiAP實施的復雜現象。

圖1 HiAP可持續實施的概念框架

2 概念框架

圖1對HiAP的實施進行了概念化,即對各方參與者來說,HiAP實施的可接受性和可行性如何。為了進一步闡明CMOs,此框架還明確了關鍵的背景因素,包括了最初影響HiAP策略的因素、政府正式實施HiAP的政策意見以及更能直接決定其實施可持續性的因素。在案例分析結果基礎上,對此框架進行了反復修改。

HiAP策略包括了多種計劃和項目,促進各層級政府部門都能夠直接或間接與初始政策承諾形成聯系。[60-61]因此每一個項目的實施都需要視為對HiAP的實施。本研究假設HiAP實施是政策變化的增值模式,隨著時間的推移可以使政府命令不斷發生變化。

2.1 指標說明

由于HiAP干預是一個持續的衛生決策過程,因此本研究以“可持續性”指標來測量政策執行的效果,其主要包括兩個方面:一是HiAP策略會被持續執行,而不受政治領導者變化的影響,二是HiAP的策略會在更廣范圍內得到推廣。

最近的研究顯示,HiAP 的“可接受性”(即某些部門是否愿意就衛生問題開展合作?)和“可行性”(即某些部門是否有能力就衛生問題開展高效合作?)是可持續性的先決條件。[62]非衛生部門的認同度會對HiAP的執行產生影響,此外,先前的經驗也表明了議程設定[33]、高效交流和對話等所能發揮的作用。[34,63-64]“可行性”似乎會受到實施過程中制度能力建設的影響,如相關的技術以及人力、財力和基礎設施等。[33-34,63-64,65-66]

但“可接受性”或“可行性”并不意味著“可持續性”的目標就一定能夠實現。例如,提高人們對多部門合作的意識可能會提高“可接受性”,但并不意味著HiAP策略的執行就具有可行性。另一方面,“可接受性”和“可行性”是可以相互促進的兩個因素,因此,HiAP實施的可持續性應該被看作是在提高“可接受性”和“可行性”之后的一種潛在可能性。

2.2 可持續性機制

HiAP的可持續性可以被視為一種分散的具有關聯性的機制功能,進而促進可接受性和可行性。這些機制通過某些特定的行動和活動來說明如何能夠說服利益相關者參與HiAP策略,還包括對其影響的認知和行為性解釋。顯然,機制與一種或多種結果密切相關。然而,機制還可以與正負協同效應互相影響,并受到結果的反作用。

機制還可以在更加廣義的背景下加以理解,這樣才能使某一地區的成功實踐經驗被其他地區的決策者理解和應用,并根據背景因素的不同進行相應的調整。某些機制還可能與某個特定背景因素密切相關。

2.3 與HiAP實施相關的背景因素

本研究對可能影響HiAP可持續性的背景因素進行了總結(圖1)。一是HiAP的政治優先權會促進該策略的實施,并且使政府領導力保持在較高水平。[67]二是HiAP實施的程序會受到一些因素的影響,包括:監督與評估、強制參與的立法以及非衛生領域評估工具的使用。[46]三是足夠的財政資金支持,即進行HiAP管理和操作所需要的可持續性成本。[41,68-69]四是促進HiAP實施所開展的其他能力構建活動,如影響力評估工具的使用培訓等。[33-34,63-66]

與HiAP執行相關的背景因素可以在衛生影響力評估過程中發生變化。[43]值得注意的是,即使在既有行政命令或資源充足的條件下,健康影響力評估的制度化有時是不完整甚至是失敗的。[70]實施的背景因素或許會影響該評估工具的可接受性和可行性,包括監督和評估健康影響是強制的還是自愿的、其使用形式是政府部門內部還是公眾參與、以及財政資金是采取何種方式支持衛生影響力評估的開展。[71]

2.4 與HiAP啟動相關的背景因素

能夠影響HiAP啟動的背景因素也會間接影響HiAP的實施。首先,HiAP策略是在某一地區內基于某一特定的文化、經濟和政治背景產生的,具體包括:如何集中或分散各級政府權力、處于資源匱乏或豐富時期的政治意識形態。[72-75]以政治意識形態舉例來說,盡管實施HiAP策略時需要達成政治上的一致性,但某些部門的政治利益或許會促進或阻礙HiAP的實施,這是因為決策者有自己的 “官僚判斷力”[76-78],而且這一判斷力的使用會隨著時間的推移以及行政管理的變化而發生改變。第二,國際組織或許會支持HiAP策略的推廣和實施。如世界衛生組織促進并支持HiAP的開展。[35,41,79]第三,某一特定的政策問題可能會促使人們接受HiAP,如對疾病負擔、公平性、可持續性或普遍人口衛生狀況的關心和關注。[67,80-81]隨著時間的推移,解決這些特定問題對于政府不同部門的利益相關者來說其利益可能會變大或變小。第四,跨部門行動的先前經驗可能有利于對HiAP產生認同,也會影響到HiAP的實施,以及與其他政府部門協同工作的能力。[14,43,82]第五,“衛生的意識形態和衛生體系”也會影響到HiAP的可接受性和可行性。事實上,盡管HiAP是基于健康社會決定因素的視角關注衛生問題的預防性行動,但某一地區內可能更加關注某一健康問題的主要決定因素的干預和介入(如生活方式),而有些地區則著重解決這些行為的結構性決定因素。[43]這些差異對產生一個更為公平的衛生服務供給方式有一定的價值。[32,46]

3 研究方法:基于現實主義的解釋性案例研究

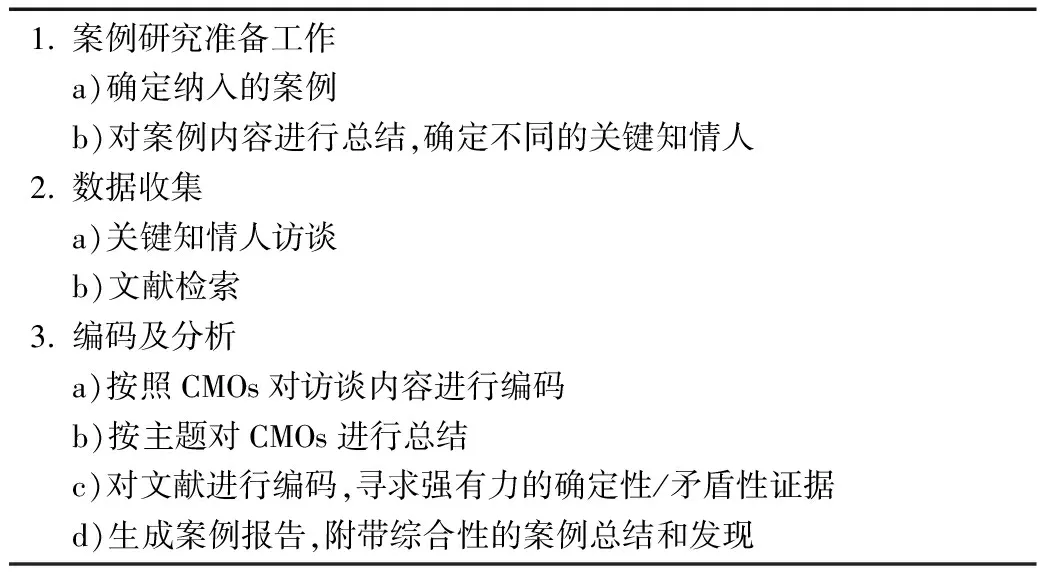

要解釋眾多合作者之間的可接受性和可行性以及不同層級政府部門能夠可持續性實施HiAP的原因,找出促進或阻礙執行的機制。本文采取基于現實主義的解釋性案例研究,對不同區域內HiAP的執行情況進行分析(表1)。

表1 解釋性案例研究的步驟

3.1 案例研究準備工作

3.1.1 確定納入的案例

本研究采用以下定義來確定要納入的HiAP案例:在一項公共衛生政策的制定過程中,需要各部門聯合協作來解決衛生不公平性的問題。此定義假定:(1)這種方法超越了單純的衛生服務,需要跨部門的行動;(2)在國家或州層面,將衛生問題置于多部門中加以考慮;(3)與HiAP相關的政策可以在多層次背景下生成多個計劃或項目。

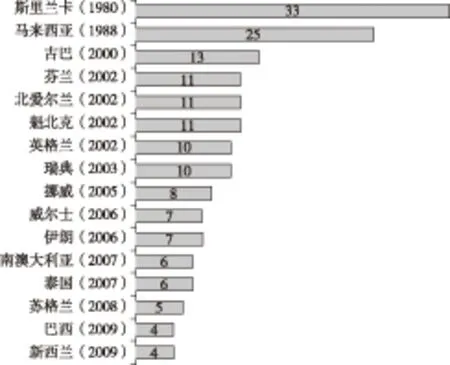

此外,本研究將HiAP案例限制在那些高度依賴國家或州級政府行政命令的案例,并確保每個案例都采用了自上而下或自下而上的機制。這種干預手段還更傾向于解決宏觀社會決定因素,并以實施步驟明確的強力指令(如立法)作為配套措施。以此定義為標準,對2010年的相關文獻進行審查,確定了16個HiAP案例(圖2)。[43]

圖2 16個地區中HiAP策略的持續時間(年)

3.1.2 對案例內容進行總結,確定不同的關鍵知情人

一旦確定某一案例,研究團隊成員會查閱全部相關文獻[14],以更好的理解每個背景下的HiAP。這包括可能對執行產生影響的背景因素,以及有關HiAP案例實施方法的描述。這些案例總結也會與潛在的關鍵知情人進行共享。

關鍵知情人的認定標準源于對文獻的復習。本研究會確保不同案例(不同部門、不同層級政府)是在文獻信息分析的基礎上進行選擇。在選擇過程和文獻復習的最后階段,研究團隊成員將會指定相關HiAP案例的關鍵知情人。所有潛在知情人都會按照其自測與HiAP實施的熟悉度進行嚴格篩選,按照likert表,從最不熟悉到非常熟悉分別賦值為1~5, 3及以上會被認定為合格。平均每個案例會尋找10~15個潛在關鍵知情人,并且會按照不同跨部門活動的綜合研究確定最終的數量。

3.2 數據收集

本研究在與關鍵知情人進行半結構式電話訪談之前,會首先進行訪談須知指導,讓知情人初步了解其在研究發揮的作用,并與其在一定主題范圍內對HiAP執行的促進或阻礙因素進行簡單討論。指導內容包括對每個主題提出相應的問題并試圖做出解釋。訪談指導會指導關鍵知情人構建相應的問題框架,從而有助于他們清晰描述各種機制并做出評估。同時,研究團隊會定期向知情人反饋數據收集的進展,確保數據能夠滿足團隊需要(即能夠明確揭示有關機制),并進一步豐富相關信息,為下一個案例的知情人訪談做好準備。與此同時對有關文獻檢索并歸類。

3.3 編碼及分析

3.3.1 按照CMOs對訪談進行編碼

訪談數據的編碼是指按照背景—機制—結果的結構對訪談內容進行標記。這些編碼有助于研究團隊更好的了解結果,如HiAP方案實施的可持續性如何等。此外,還對與HiAP方案實施可持續存在因果關系的相關因素進行編碼,能夠反映出跨部門合作的一些特點。另外,其他編碼對段落的認定可以幫助將機制置于某種背景下進行分析。對于每一個案例來說,訪談副本都會由兩個研究團隊成員進行仔細且系統的獨立編碼。

3.3.2 按主題對CMOs進行總結

完成某一案例的初始編碼后,將會召開團隊會議對訪談數據進行整合,對所有已編碼的機制進行討論,分析某種機制如何以及為何會引發相關的結果以及哪些內容(背景因素和其他CMOs表達)可能與核心工作機制比較一致。基于不同關鍵知情人形成的CMOs資料,按相同機制模式對其進行分組,按照不同的主題對每個案例進行總結和概括。一個案例的總結工作完成后,通過關鍵知情人訪談對數據進行復審,并對其他資料進行解讀。本研究盡可能多次重復這種數據調查和審查過程,從而提煉出有關此案例有用的觀點和理論。[83]

3.3.3 對文獻進行編碼,尋求強有力的確定性/矛盾性證據

本研究對所有與此案例有關的文獻(包括在關鍵信息人訪談中獲取的相關內容)進行檢索,以尋求能夠支持或否定這一機制的證據。詳細列出各個案例中的相關文獻證據,包括機制的簡要描述、政府層級(國家、州/省、市)以及相關的主題內容。本研究所采納的文獻只包括那些具有說服力的證據,即能夠直接支持或明確反駁之前訪談中提到的某一機制,并將其整合到相關的案例分析中。

3.3.4 生成案例報告,附帶綜合性的案例總結和發現

最后形成的案例總結報告將指出HiAP案例的實施為什么是成功的,明確每個案例的特點及背景因素如何影響HiAP的實施,[84]并指出在一個既定背景下,不同因素和不同戰略如何以及為何會與HiAP方案執行的可持續性產生關聯。報告具體包含以下內容:(1)基于新的訪談證據或其他資料而形成的新修訂的報告摘要;(2)對機制進行詳細闡述,分析了某一地區的HiAP方案如何、為何以及在何種條件下在跨部門之間開展實施工作。此外,該報告還包括大量來自關鍵知情人和文獻的關鍵語錄,以闡明一種特定機制的作用或一種背景因素的影響力。

4 結果

本文運用基于現實主義的解釋性案例研究方法對瑞典、加拿大魁北克和南澳大利亞HiAP方案的執行情況進行了研究。以瑞典為例,闡述了其在HIA執行的能力構建中所積累的成功實踐經驗,包括衛生影響力評估為何能夠得到貫徹實施,以及影響執行可接受性和可行性的某些特定背景因素。此外,本研究還會從魁北克的案例中提取證據,證明跨區域背景下實施HiAP是可行的,并驗證某一區域內的機制所能發揮的作用。

在整個分析過程中涉及兩個假設:一是HIA方案的執行需要政府加強技術和能力建設, 另外一個相對假設是,HiAP的詳細執行戰略本身是高效的,各部門可以調整相應的能力以適應衛生影響力評估的實施。本研究基于關鍵知情人訪談和文獻證據,明確闡述了成功(或不成功)進行衛生影響力評估的政府部門機制是怎樣的,并提供具體證據來說明關鍵知情人在分析過程中是如何看待CMOs數據的。如瑞典的關鍵知情人認為:“使用HIA的部門越來越少了。許多人認為從理論上來說這個想法不錯,但實際執行起來卻太難了,而且如何衡量實際情況以及財政資金如何使用,都很成問題。從法律上來講,使用這些HIA也不是強制法令。”由此可以看出,瑞典HIA并不是基于法律背景下實施的,非衛生部門可能會因為不理解如何使用這一工具以及缺乏執行的財政能力而放棄。另一位瑞典關鍵知情人提到:“一些新概念的引入,需要在已有部門之內的機制和程序中展開,這可能給部門增添了一些干擾和新的工作負擔……,對于一個部門來說,深刻領會這些新東西的積極性。”這表明了當引入的活動對于一個區域來說比較新,很容易被整合到既定的機制中。

這些關于瑞典HIA使用情況的確定性證據對于那些已參與環境影響評估(EIA)的部門來說具有促進作用。自20世紀90年代以來,在環境法典的約束下,EIA一直都是瑞典評估環境對人類健康影響決策的強制性指令。同時,研究也發現,之前不具備EIA經驗的部門則需要更多時間去接受和使用衛生影響力評估。

這表明,在已經熟悉并使用其他評估工具的部門,衛生影響力評估要想成功實施,應將其整合到既有的評估框架或工具中。這一戰略也得到了本研究自行設計的理論框架(上述)以及國家公共衛生政策合作中心提出的執行框架的支持。這意味著由于相似性可能會影響到實施的可行性(參與者利用現有項目的經驗促進其實施)。[62]

但這種特定機制是瑞典獨有的特點。瑞典和魁北克的實施背景是不同的。一是魁北克立法(公共衛生法案)要求在省級強制實施衛生影響力評估,而對于非立法背景下的瑞典,意味著只能通過部門的自律性來完成公共衛生中的某些目標。二是魁北克跨部門合作的程序由各機構協商完成,而瑞典主要由國家公共衛生協會進行協調。因此,盡管兩個地區都實施了衛生影響力評估,但魁北克的相關立法工作及具體明確的使用程序和細節可以促進此項目的開展。

5 討論

5.1 研究方法的優勢

本研究所采用的解釋性案例研究運用三角測量的方法,具有明顯的優勢:多種循證證據支持,包括已出版的灰色文獻和同行評議文獻、對關鍵知情人的訪談以及案例相關文件;不同的研究方法,包括解釋性案例研究和現實主義評估;以及組成研究團隊對證據解讀,構建CMOs并進行總結。多種數據資源的使用能夠產出大量有關HiAP機制的相關數據,能夠為如何以及為何會發生這種特定現象提供證據支持。[15,52,56,85-87]

此方法還可以支持對因果關系的推測和了解,在敘述過程中使相關關系變得更加清晰,從而改善大多數定量研究中對固有因果方向的模糊性認識。[41,50-54,60]

此研究為其他地區和背景下的決策者評估HiAP執行提供普適性的成功經驗。在案例研究過程中,將清晰闡明研究者的行為以及這樣做的原因。采用描述性分析方式,將研究方法描述成一種研究過程。在研究過程中真實記錄了數據中存在的差異,并試圖通過關鍵知情人的訪談來解決這些問題。

此外,案例研究保持了高度一致性,包括對案例的選擇、文獻的系統檢索、案例總結報告的書寫、關鍵知情人訪談以及相關案例文件的分析。

5.2 研究方法的局限性

某些重要機制或許不可能僅僅依靠每個案例中15個知情人的回憶而全部展現出來。首先,雖然本研究試圖納入所有層次的關鍵知情人,但不可能從每一個案例中所有政府層級中抽取所有參與者。第二,在討論實施過程中可能存在的促進或阻礙因素時,相關的信息比較多,但為減輕參與者的負擔,每次訪談時間限制在一小時之內。因此,關鍵知情人提供的信息可能不夠全面。最后,關鍵知情人的認識水平也會受到自身職位(如技師/工程師、經理、研究員、決策者或政治家)的限制。

在HiAP戰略實施的過程中,有關如何以及為何某些行動會產生相應的結果,通過研究方法也許會得到矛盾性證據。在這種情況下,盡管可能無法立即得出一個全然一致的結果,但本研究團隊依然在試圖進一步與關鍵知情人討論那些無法達成一致結果的原因,并重新審閱相關文件,以獲得更加一致的信息。

6 結論

盡管人們越來越認識到加強衛生的宏觀社會決定因素研究的重要性,但政府在協調衛生服務之外的相關行動以拓寬衛生體系的努力還依然不夠。此外,有關鼓勵政府采用跨部門合作以改善人口健康狀況的系統研究也很少。HiAP可謂是未來重要的干預手段之一,其可以通過將廣義衛生決定因素作為目標,從而系統化地解決衛生決策問題。本文采用的研究方法提供了一種新的視角,旨在基于大量證據,描述特定地區內HiAP成功實施所具備的社會機制和突出的背景因素。這種方法還可以應用到其他形式的跨部門研究。解釋性案例研究基于一套嚴格的概念框架,可以審視和檢驗全球所有地區成功實踐經驗所具有的一致性。

致謝

感謝瑞典、魁北克和南澳大利亞關鍵知情人接受我們的訪談,感謝研究團隊的其他成員為本文提供的幫助。

[1] Bernier N F.Quebec’s approach to population health: an overview of policy content and organization[J]. J Public Health Policy, 2006, 27(1): 22-37.

[2] Bierman A S. Project for an Ontario Women’s Health Evidence Based Report[R]. Toronto: Echo: Improving Women’s Health in Ontario, 2009.

[3]Bierman A S. Project for an Ontario Women’s Health Evidence Based Report[R]. Toronto: Echo: Improving Women’s Health in Ontario, 2010.

[4] Commision on the Social Determinants of Health (CSDH). Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health[R]. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2008.

[5] Freiler A, Muntaner C, Shankardass K et al. Glossary for the implementation of health in all policies (HiAP)[J]. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 2013, 67(2): 1068-1072.

[6] Greenhalgh T, Russell J, Ashcroft R E, et al. Why national eHealth programs need dead philosophers: Wittgensteinian reflections on policymakers’ reluctance to learn from history[J]. Milbank Quarterly, 2011, 89(4): 533-63.

[7] Greenhalgh T, Wong G, Westhorp G, et al. Protocol—realist and meta-narrative evidence synthesis: evolving standards (RAMESES)[J]. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 2011, 11: 115.

[8] Jagosh J, Pluye P, Macaulay AC et al. Assessing the outcomes of participatory research: protocol for identifying, selecting, appraising and synthesizing the literature for realist review[J]. Implementation Science, 2011, 6: 24.

[9] Jagosh J, Macaulay A C, Pluye P, et al. Uncovering the benefits of participatory research: implications of a realist review for health research and practice[J]. Milbank Quarterly, 2012, 90(2): 311-46.

[10] Jacobs J A, Jones E,Gabella B A, et al. Tools for implementing an evidence-based approach in public health practice[J]. Preventing Chronic Disease, 2012, 9: E116.

[11] Macaulay A C,Jagosh J, Seller R, et al. Assessing the benefits of participatory research: a rationale for a realist review[J]. Global Health Promotion, 2011, 18(2): 45-48.

[12] Macfarlane F,Greenhalgh T, Humphrey C, et al. A new workforce in the making? A case study of strategic human resource management in a whole-system change effort in healthcare[J]. Journal of Health Organization and Management, 2011, 25(1): 55-72.

[13] Noble D,Mathur R, Dent T, et al. Risk models and scores for type 2 diabetes: systematic review[J]. British Medical Journal, 2011, 343: d7163.

[14] Shankardass K, Solar O, Murphy K, et al. A scoping review of intersectoral action for health equity involving governments[J]. International Journal of Public Health, 2012, 57(1): 25-33.

[15] Wong G,Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G,et al. Realist methods in medical education research: what are they and what can they contribute? [J]. Medical Educaation, 2012, 46(1): 89-96.

[16] Berkman L F. Social epidemiology: social determinants of health in the United States: are we losing ground? [J]. Annual Review Public Health, 2009, 30: 27-41.

[17] Clair S, Singer M.Syndemics and public health: reconceptualizing disease in bio-social context[J]. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 2003, 17: 423-441.

[18] Dahlgren G, Whitehead M. Policies and Strategies to Promote Social Equity in Health[R]. Stockholm: Institute for Future Studies, 1991.

[19] Krieger N. Theories for social epidemiology in the 21st century: anecosocial perspective[J]. International Journal of Epidemiology, 2001, 30(4): 668-677.

[20] Measurement and Evidence Knowledge Network. The Social Determinants of Health: Developing an Evidence Base for Political Action Final Report to World Health Organization Commission on the Social Determinants of Health[R]. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2007.

[21]Muntaner C, Lynch J W, Hillemeier M, et al. Economic inequality, working-class power, social capital, and cause-specific mortality in wealthy countries[J]. International Journal of Health Services, 2002, 32(4): 629-56.

[22] Navarro V. What we mean by social determinants ofhealth[J]. Global Health Promotion, 2009, 39(3): 423-441.

[23] Thomas Y,Sterk C. Social epidemiology and behavioral health: methodologic approaches, problems, and promise[J]. American Journal of Epidemiology, 2008, 167: S42.

[24] Venkatapuram S, Marmot M. Epidemiology and social justice in light of social determinants of health research[J]. Bioethics, 2009, 23(2): 79-89.

[25] Woolf SH. Social policy as healthpolicy[J]. Journal of the American Medical Association, 2009, 301(11): 1166-1169.

[26] Harris E. Working together:intersectoral action for health[R]. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service, 1995.

[27] Milio N. Multisectoral policy and health promotion: where to begin?[J]. Health Promotion International, 1986, 1: 129-132.

[28] Milio N. Making healthy public policy; developing the science by learning the art: an ecological framework for policy studies[J]. Health Promotion International, 1987, 2: 263-274.

[29] O’Campo P, Kirst M, Schaefer-McDaniel N, et al. Community-based services for homeless adults experiencing concurrent mental health and substance use disorders: a realist approach to synthesizing evidence[J]. Journal Urban Health, 2009, 86(6): 965-989.

[30] Public Health Agency of Canada. Crossing Sectors: Experiences in Intersectoral Action, Public Policy and Health[R]. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada, 2007.

[31] Public Health Agency of Canada. Health Equity through Intersectoral Action: An Analysis of 18 Country Case Studies[R]. Ottawa: WHO, Minister of Health, 2008.

[32] Solar O, Valentine N, RiceM,et al. Moving forward to Equity in Health: What kind of Intersectoral Action is needed? An Approach to an Intersectoral Typology[R]. Nairobi, 2009.

[33]Teran F A O, Cole D C. Developing cross sectoral, healthy public policies: a case study of the reduction of highly toxic pesticide use among small farmers in Ecuador[J]. Social Medicine, 2011, 6: 83-94.

[34] Thow A M, Snowdon W, Schultz J T, et al. The role of policy in improving diets: experiences from the Pacific obesity prevention in communities food policy project[J]. Obesity Reviews, 2011, 12(Suppl 2): 68-74.

[35] WHO and Government of South Australia.Adelaide Statement on Health in All Policies[R]. Adelaide: WHO, 2010.

[36] Anonymous.Introduction[J]. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 2004, 32: 4-5.

[37] The Helsinki Statement on Health in All Policies[R].Helsinki, 2013.

[38] Greaves L J, Bialystok L R. Health in All Policies—all talk and little action?[J]. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 2011, 102(6): 407-419.

[39] O’Campo P, Kirst M, Tsamis C, et al. Implementing successful intimate partner violence screening programs in health care settings: evidence generated from a realist informed systematic review[J]. Social Science Medicine, 2011, 72(6): 855-866.

[40] Sanders D, Haines A. Implementation research is needed to achieve international healthgoals[J]. PLoS Medicine, 2006, 3(6): e186.

[41] McQueen D V, Wismar M, Lin V, et al.Intersectoral governance for health in all policies: structures, actions and experiences[R]. Copenhagen: World Health Organization, 2012.

[42] Public Health Agency of Canada. Health Equity through Intersectoral Action: An Analysis of 18 Country Case Studies[R]. Ottawa: WHO, Minister of Health, 2008.

[43]Shankardass K, Solar O, Murphy K, et al. Health in all policies: results of a realist-informed scoping review of the literature. Getting Started With Health in All Policies: A Report to the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care[R]. Toronto: Centre for Research on Inner City Health, 2011.

[44] Leppo K, Ollila E, Pena K, et al. Health in All Policies: Seizing Opportunities, Implementing Policies[R]. Helsinki: Ministry of Social Affairs and Health of Finland, 2013.

[45]Sta°hl T, Wismar M, Ollila E, et al. Health in All Policies: Prospects and Potentials[R]. Finland: Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, 2006.

[46] St. Pierre L. Governance Tools and Framework for Health in All Policies[R]. Quebec: National Collaborating Centre for Healthy Public Policy, International Union for Health Promotion and Education and European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2009.

[47] Connelly J B. Evaluating complex public health interventions: theory, methods and scope of realistenquiry[J]. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 2007, 13(6): 935-941.

[48] Muntaner C, Lynch J. Income inequality, social cohesion, and class relations: a critique of Wilkinson’s neo-Durkheimian research program[J]. International Journal of Health Services, 1999, 29: 59-81.

[49] Muntaner C. Invited commentary: social mechanisms, race, and social epidemiology[J]. American Journal of Epidemiology, 1999, 150: 121-126.

[50] Best A,Greenhalgh T, Lewis S, et al. Large system transformation in health care: a realist review[J]. Milbank Quarterly, 2012, 90(3): 421-456.

[51] Lavin T, Metcalfe O. Policies and Actions Addressing the Socio-Economic Determinants of Health Inequalities: Examples of Activity in Europe[R]. Dublin: Institute of Public Health in Ireland, 2008.

[52]Pawson R, Greenhalgh T, Harvey G,et al. Realist review—a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy, 2005, 10(Suppl1): 21-34.

[53] Taylor C, Gibbs G R. How and What toCode[EB/OL].. onlineqda.hud.ac.uk/Intro_QDA/how_what_to_code.php, accessed 22 March 2014.

[54] Wong G,Greenhalgh T, Pawson R. Internet-based medical education: a realist review of what works, for whom and in what circumstances[J]. BioMed Central Medical Education Medical Education, 2010, 10(12): 12.

[55] Kaufman J S,Hernan M A. Epidemiologic methods are useless: they can only give you answers[J]. Epidemiology, 2012, 23(6): 785-786.

[56] Lemire S T, Nielsen S B, Dybdal L. Making contribution analysis work: a practical framework for handling influencing factors and alternative explanations[J]. Evaluation, 2012, 18: 294-309.

[57] Woiceshyn J. Causal case study: explanatory theories[M]. //Mills A J, Durepos G, Wiebe E. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research. New York: Sage Publications, Inc, 2010.

[58] Yin R K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods[R]. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2009.

[59] Merton R K. Social Theory and SocialStructure[M]. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1968.

[60] Clark A. Critical realism[M].// Given L M. Sage Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods. California: Sage, 2008.

[61] Lawless A, Williams C, Hurley C, et al. Health in all policies: evaluating the south Australian approach tointersectoral action for health[J]. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 2012, 103(Suppl 1):S15-S19.

[62]Morestin F, Gauvin F P, Hogue M C, et al. Method for Synthesizing Knowledge about Public Policies[R]. Montreal: National Collaborating Center for Healthy Public Policy, 2010.

[63] Finer D,Tillgren P, Berensson K, et al. Implementation of a health impact assessment (HIA) tool in a regional health organization in Sweden—a feasibility study[J]. Health Promotion International, 2005, 20(3): 277-284.

[64] O’Neill M, Lemieux V,Groleau G, et al. Coalition theory as a framework for understanding and implementing intersectoral health-related interventions[J]. Health Promotion International, 1997, 12(1): 79-87.

[65]Mannheimer LN, Gulis G, Lehto J, et al. Introducing health impact assessment: an analysis of political and administrative intersectoral working methods[J]. European Journal of Public Health, 2007, 17(5): 526-531.

[66] Mannheimer L N, Lehto J, Ostlin P. Window of opportunity for intersectoral health policy in Sweden—open, half-open or halfshut?[J]. Health Promot Int, 2007, 22(4): 307-315.

[67] Kingdon J W. Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies[M]. Boston: Little, Brown & Co, 1984.

[68] Anonymous.Pooling Resources across Sectors: Summary of a New Report for Local Strategic Partnerships[R]. London: Health Development Agency, 2004.

[69] Drummond M,Stoddart G. Assessment of health producing measures across different sectors[J]. Health Policy, 1995, 33(3): 219-231.

[70] Wismar M,Blau J, Ernst K, et al. The effectiveness of health impact assessment: scope and limitations of supporting decision-making in Europe[R]. Copenhagen: European Observatory on Health Systems, WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2007.

[71]Shankardass K, Solar O, Murphy K, et al. Health in all policies: 16 case descriptions. Getting Started With Health in All Policies: A Report to the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care[R]. Toronto: Centre for Research on Inner City Health, 2011.

[72] Chung H,Muntaner C, Benach J. Employment relations and global health: a typological study of world labor markets[J]. International Journal of Health Services, 2010, 40(2): 229-253.

[73] Saint-Arnaud S, Bernard P. Convergence or resilience? A hierarchical cluster analysis of the welfare regimes in advancedcountries[J]. Current Sociology, 2003, 51: 499-527.

[74] Solar O, Irwin A. A Conceptual Framework for Action on the Social Determinants of Health: Discussion Paper for the Commission on Social Determinants of Health[R]. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2007.

[75] Timpka T, Nordqvist C, Lindqvist K. Infrastructural requirements for local implementation of safety policies: the discordance between top-down and bottom-up systems of action[J]. BMC Health Serv Res, 2009, 9: 45.

[76] Balla S J. Administrative procedures and political control of the bureaucracy[J]. American Political Science Review, 1998, 92(3): 663-673.

[77] Bossert T. Analyzing the decentralization of health systems in developing countries: decision space, innovation and performance[J]. Social Science & Medicine, 1998, 47(10): 1513-1527.

[78] Thompson FJ. Bureaucratic discretion and the National Health ServiceCorps[J]. Political Science Quarterly, 1982, 97: 427-445.

[80] Exworthy M. Policy to tackle the social determinants of health: using conceptual models to understand the policy process[J]. Health Policy Plan, 2008, 23(5): 318-327.

[81] Tervonen-Goncalves L, Lehto J. Transfer of Health for All policy—What, how and in which direction? A two-case study[J]. Health Research Policy System, 2004, 2: 8.

[82] British Medical Association. Health and Environmental Impact Assessment: An IntegratedApproach[M]. London: Earthscan Publications Ltd, 2009.

[83] O’Campo P, Shankardass K, Bayoumi A, et al. A Realist Synthesis of Initiation of Health in All Policies (HiAP): intersectoral perspectives[R]. Toronto: Centre for Research on Inner City Health, 2011.

[84] Stake RE.Multiple Case Study Analysis[M]. New York: The Guilford Press, 2006.

[85] Bhaskar R. A Realist Theory of Science[R]. Leeds, 1975.

[86] Greenhalgh T, Humphrey C, Hughes J, et al. How do you modernize a health service? A realist evaluation of whole-scale transformation in London[J]. Milbank Quarterly, 2009, 87(2): 391-416.

[87] Hummelbrunner R. Systems thinking and evaluation[J]. Evaluation, 2011, 17: 395-403.

(編輯 趙曉娟)

Strengthening the implementation of Health in All Policies: A methodology for realist explanatory case studies

KetanShankardass1,2,3,EmilieRenahy2,CarlesMuntaner2,3,4,PatriciaO’Campo2,3

1.DepartmentofPsychology,WilfridLaurierUniversity,WaterlooN2L3C5,Canada2.CentreforResearchonInnerCityHealth,St.Michael’sHospital,TorontoM5B1W8,Canada3.DallaLanaSchoolofPublicHealth,UniversityofTorontoTorontoM5S2J7Canada4.BloombergFacultyofNursing,UniversityofToronto,TorontoM5S2J7Canada

To address macro-social and economic determinants of health and equity, there has been growing use of intersectoral action by governments around the world. Health in All Policies (HiAP) initiatives are a special case where governments use cross-sectoral structures and relationships to systematically address health in policymaking by targeting broad health determinants rather than health services alone. Although many examples of HiAP have emerged in recent decades, the reasons for their successful implementation—and for implementation failures—have not been systematically studied. Consequently, rigorous evidence based on systematic research of the social mechanisms that have regularly enabled or hindered implementation in different jurisdictions is sparse. We describe a novel methodology for explanatory case studies that use a scientific realist perspective to study the implementation of HiAP. Our methodology begins with the formulation of a conceptual framework to describe contexts, social mechanisms and outcomes of relevance to the sustainable implementation of HiAP. We then describe the process of systematically explaining phenomena of interest using evidence from literature and key informant interviews, and looking for patterns and themes. Finally, we present a comparative example of how Health Impact Assessment tools have been utilized in Sweden and Quebec to illustrate how this methodology uses evidence to first describe successful practices for implementation of HiAP and then refine the initial framework. The methodology that we describe helps researchers to identify and triangulate rich evidence describing social mechanisms and salient contextual factors that characterize successful practices in implementing HiAP in specific jurisdictions. This methodology can be applied to study the implementation of HiAP and other forms of intersectoral action to reduce health inequities involving multiple geographic levels of government in diverse settings.

Health policy; Implementation; Health promotion; Equity; Determinants; Social Determinants; Social epidemiology

加拿大衛生研究協會資助項目(111608);安大略省衛生部資助項目(96566)

Ketan Shankardass,男,博士,助理教授,主要研究方向為流行病學。E-mail: kshankardass@wlu.ca

10.1093/heapol/czu021, 略有刪減。

R197

A doi:10.3969/j.issn.1674-2982.2015.03.014

2015-01-26

2015-03-26

本文英文原文參見Health Policy and Planning, 2014: 1-12,