艾米麗·勃朗特:“我沒有怯懦的靈魂”

By Ron Charles

Even the light of 200 birthday candles couldnt pierce the gloom of Wuthering Heights. But the fire that burned within Emily Bront? roars across the centuries.

How remarkable that on the bicentennial1 of her birth, this reclusive woman should still be crying at our window like Catherine, “Let me in—let me in! Im come home!”

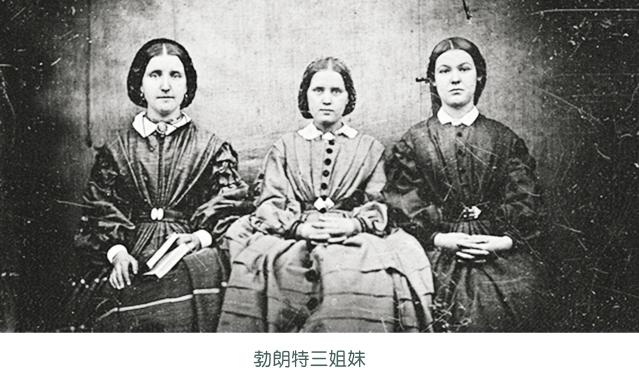

The younger sister of Charlotte, Emily was born on July 30, 1818, in Yorkshire, England, to Maria Branwell, who died just a few years later, and Patrick Bront?, a parish priest. Together with her two sisters, Emily stoked a furnace of creativity unique in the annals of literary history.2 The children wrote fantastical stories together, spinning imaginary worlds of romantic and military adventure.

《呼嘯山莊》堪稱英語(yǔ)文學(xué)史上的一部曠世奇作,冰冷寂寥的漫漫荒野、永無(wú)止境的殘酷黑暗、肆意揮灑的愛恨情仇……盡管這部作品如今被視為難以超越的佳作,在首次出版的年代里卻備受爭(zhēng)議與抨擊,而作者艾米麗·勃朗特那充滿遺憾與寂寥的短暫人生也令后人唏噓不已。一生僅一部小說(shuō),艾米麗似乎將生命中所有熾熱的情感與能量都傾注于這片陰冷的荒野,用超越時(shí)代與世俗的浪漫奇想編織出了一段飛揚(yáng)跋扈的癡狂虐戀。在她二百周年誕辰之際,我們?nèi)匀粦涯钪瑧涯钪谖膶W(xué)史上書寫的那筆優(yōu)美凄絕的永恒。

Only poetic remnants of that juvenilia survive today, but during their brief lives, each of the Bront? sisters managed to publish at least one novel, and none of them generates more cultish devotion than Wuthering Heights.3 Yes, Charlottes Jane Eyre may have more readers, but the tale of young Catherine and Heathcliff, the mysterious bad boy who is really bad, remains the most feverish love story in English literature.

Given that blaze of fury and passion, filmmakers have been drawn to Bront?s bleak moors as inexorably4(and disastrously) as Catherine is attracted to Heathcliff. Everyone from Laurence Olivier to Timothy Dalton to Ralph Fiennes has taken a stab at “that devil.” In 2015, the Lifetime network set Wuthering High School in Malibu, which is not so much an adaptation as a desecration5. Perhaps the plot is simply too static and vast to capture on screen, which may be why Kate Bushs otherworldly single “Wuthering Heights” (1978) remains the best homage.6

The books fame was hardly preordained. Published in 1847 under the masculine pseudonym Ellis Bell, Wuthering Heights struck its first readers as “a perfect misanthropists7 heaven.” Early reviewers called it “strange,” “disagreeable,” “baffling,” “disjointed”and even “inexpressibly painful.” All true, but they made that sound like a bad thing. One reviewer was particularly distressed by the novels dismal gloominess. “Never was there a period in our history,” he concluded, “when we English could so ill afford to dispense with sunshine,” which sounds like he was that guy who walks up to women and says, “Come on, girl: Give us a smile!”

For sure, Emily was not prone to giddiness8. But despite the extraordinary fame of her single novel, she remains obscured by fog, which only makes her more attractive for our own projected fantasies of savage romantic abandon. She was, reportedly, shy and private. A family member claimed she rarely left the house except for church or to walk alone. Our impression of her is further clouded by Charlottes heavy-handed efforts to tidy up her little sisters reputation after she died in 1848. In a perplexing preface to the second edition of Wuthering Heights, Charlotte praised the novel—“We seem at times to breathe lightning”—while also questioning the wisdom of creating a character like Heathcliff. She went on to suggest that Emily was not a talented artist so much as a natural genius, “a native and nursling of the moors” who worked “in a wild workshop, with simple tools, out of homely materials.” Its a surprisingly chauvinistic9 argument, and factually untrue, given Emilys wide reading of Romantic literature—in English and German. At the peak of her sisterly betrayal, Charlotte wrote, “Having formed these beings, she did not know what she had done.”

In fact, we do not know what Emily has done.

Long after Wuthering Heights should look rusted by time and softened by familiarity, it remains an extravagantly turbulent novel.10 As a teenager, I found the story, with its nested narrators and tangled family tree, baffling and dull. Rereading it this month, though, I was dazzled by its preternatural11 modernity. The way the characters resist any moral explanation, the way the style flickers between gothic romanticism and flinty realism, and the way the incestuous plot festers past all endurance on that claustrophobic moor—its shockingly daring.12 Charlotte didnt have the nerve to leave her little Jane Eyre in the red-room for more than a few hours, but Wuthering Heights reads as though Catherine never came out.

The novelist Kate Mosse is one of many luminaries13 celebrating Emilys bicentennial with the Bront? Parsonage Museum in Haworth. She writes via email, “There is no apology within Wuthering Heights, no attempt to make the story palatable14 or the characters likable or domestic, but instead it has an unashamed sense of its own purpose, its own self.”

Emily, after all, is the woman who wrote, “No coward soul is mine/No trembler in the worlds storm-troubled sphere.” And the characters she created are just as fearless, just as audacious15 in their disregard for what is expected, what is reasonable, what makes sense. Their relentless pettiness, their meanness, their physical and emotional abuse, including knife-throwing and dog-hanging—I dont deny the repulsiveness of any of that behavior; the story would make an effective Human Resources PowerPoint presentation on Disruptive Behavior Procedures. But romantic tragedy is cathartic16, not instructive. The wonder of Wuthering Heights is its exponential emotions: “such anguish in the gush of grief!”17

We know Catherine is doomed and Heathcliff is “a fierce, pitiless, wolfish man,” but how subversive, how bewitching such unbridled passion feels in our self-conscious age of transactional hookups and enlightened unions.18 No dating app would ever bring these two lovers together; no marriage algorithm would ever predict a happy future. And yet... “Hes more myself than I am,” Catherine cries. “Whatever our souls are made of, his and mine are the same.”

Such romantic fusion is a catastrophe that irradiates the realm of Wuthering Heights and leaves a blast area that should warn others away, but who can resist approaching that crater of heartache and feeling the heat that comes off these pages?19

In a poem dated 1843, Emily wrote:

Farewell then, all that love

All that deep sympathy;

Sleep on, Heaven laughs above—

Earth never misses thee.

Youre wrong, Emily. Two hundred years later, we still miss you.

盡管二百根生日蠟燭的火光也未能穿透《呼嘯山莊》的幽暗氣息,艾米麗·勃朗特內(nèi)心的熾熱火焰卻蔓延了數(shù)個(gè)世紀(jì),依舊熊熊燃燒。

不同尋常的是,在二百周年誕辰之際,這位避世隱居的女性仍舊如凱瑟琳那般在窗外大聲呼喊:“讓我進(jìn)去——讓我進(jìn)去!我回家了!”

艾米麗是夏洛蒂的妹妹,于1818年7月30日出生在英格蘭約克郡,其母瑪麗亞·布蘭韋爾在幾年后就去世了,父親帕特里克·勃朗特是一名教區(qū)牧師。艾米麗和她的兩位姐妹一同在文學(xué)編年史上留下了獨(dú)特的非凡創(chuàng)造。年少的她們一同寫就充滿奇想的故事,編織著一個(gè)個(gè)想象中的充滿浪漫而大膽的冒險(xiǎn)世界。

盡管勃朗特三姐妹年少時(shí)期的作品中僅有詩(shī)歌得以留存,但在她們短暫的人生中,每個(gè)人都至少有一部小說(shuō)得以出版,而《呼嘯山莊》便是其中受到最多狂熱追捧的佳作。