作為公共空間的交通樞紐

張利/ZHANG Li

當代生活的一個重要部分是移動性。以任何現在的都市居民而言,日常生活的時間有很大比例是在公共交通空間里度過的。哪種形式的公共交通是最好的公共交通?對此每個都會有不同的答案。不過21世紀的城市設計家們似乎在這個問題達成了一定程度的共識:由軌道(重軌或輕軌)連接的超級密度組團是最值得提倡,也是最具可持續性的[1]。類似的,在當今的城市更新項目中,不管是在發達國家的城市還是發展中國家的新興城市,與軌道交通相關的基礎設施更新也是頗受關注的熱點。我們經常體會到的現象是,無論對于城市的居民還是對于城市的造訪者來說,軌道交通空間已經成為了事實上的城市識別性的締造者之一。軌道交通(換乘)樞紐中的聲音、氣味、觸感與背景氛圍共同交織成了一種難以忘懷的經歷,以不可忽視的方式參與了我們生活品質的定義。

軌道交通(換乘)樞紐是城市化的產物,其出現可追溯到工業化的初期。然而就像現代城市本身經歷了很長的歷程才認識要把人放回到一切考慮的中心一樣,交通樞紐在接受自己是普通人的城市公共空間這一角色定位之前,也經歷了漫長的技術至上與形像崇拜過程。過剩的石頭與鑄鐵的紀念性曾一度是帝國式的經濟進步的標志。超尺度的屋蓋與巨型的內部空間讓交通樞紐更像是宮殿而不是站房。令人頗感意外的是,這一源自歐洲帝國主義時代的交通建筑紀念性傳統在歷史上竟獲得了比產生它的那些帝國更長的生命力。從傳統的城市到新興的城市,對交通樞紐紀念性形像的追求似乎令人欲罷不能。在20世紀的莫斯科我們看到宮殿式、博物館式的地鐵站的繁盛。在21世紀我國的新城我們看到高鐵站構筑的宏偉。在最近的紐約,我們再次見到了以夸張的技術表現樞紐形像的高顯現度案例——只不過其實現的材料是透明玻璃和白色金屬,而不是石頭與鑄鐵罷了。

具有諷刺意味的是,作為公共空間的交通樞紐出現于一個與之并不相容的政治氣候中。20世紀第二個10年,以在西方各國影響加劇的經濟危機為背景,莫索里尼政權的主要政策定型并開始主導主要意大利城市的進程。在隨后的一段時間中,作為刺激經濟的主要手段,各大城市紛紛在中心區域進行以公有資金支持的大型交通基礎設施建設。1933年佛羅倫薩的主火車站競賽把以米凱盧奇為首的年輕建筑師團隊推向了前臺,他們設計方案所承載的“對新建筑的宣揚直接引發了一場在(政治允許的)界限內的爭論,而這一爭論針對的是(對公共交通空間屬性的)立場與獨特解決方法”[2]。這一“爭論”的焦點或“獨特解決方法”所指的正是與城市標高取平的大通廊空間(不再被有意架高)集成大量的日常城市服務功能。當然,佛羅倫薩主火車站當年的城市性空間與今天的同類空間在尺度上與豐富程度上都不可同日而語,但它確實是一個典型的早期案例,不僅對火車站、也對所有城市公共交通樞紐給予了一種新的定義,在這種定義下,強功能性的車站與泛功能性的城市公共空間之間的界限開始被跨越。

80余年以后的今天,我們幾乎可以安心地說,交通樞紐已越來越多地被默認是城市公共空間的重要類型。雖然反例還是屢見不鮮,但絕大多數的交通樞紐對待人性化體驗的態度是嚴肅的。我們可以通過4個特性來識別這一交通樞紐向人性化公共空間轉型的進程。

第一個特性是給予慢行交通以空間主導權,設計大面積的連續延展表面以供行人與自行車使用。多數現代交通樞紐或換乘中心會有意弱化傳統車站的通廊與候車室構架,而用室內的公共廣場和街道來對其進行替代。無論在新建交通樞紐還是老舊車站的改造中,這一屬性都有著相當明顯的表達。蘇黎世中心車站的改造索性把老站房的內部全部清空,形成一個完整的室內公共空間,類似一個傳統的城市中心市場。這種類型學的功能柔性與空間活力可謂是任何21世紀國際都市的主要加分項目之一。

第二個特性是在交通樞紐空間內集成豐富的休閑與公共服務功能。不僅是零售、咖啡、餐廳等傳統的交通輔助功能,還包括畫廊、游戲廳、展覽廳甚至電影廳和圖書館等文化休閑功能。這在近期新一輪的歐洲城市火車站建設中非常普遍。代爾夫特新的中心火車站顯然沒有忘記其城市的塑造者——代爾夫特技術大學的存在,因而在火車站的水平向大廳中設置了多個新能源技術汽車的展臺,把大廳變成了展廳。現代的交通樞紐看來對于這種新的公共空間角色是越來越自信了,它們有理由相信,即使是最行色匆匆的過客,也會因空間設計質量與內容的提升而在交通樞紐內多停留一段時間,而正是這種剩余停留時間人次的積累,使得交通樞紐作為公共空間的成色越來越足。

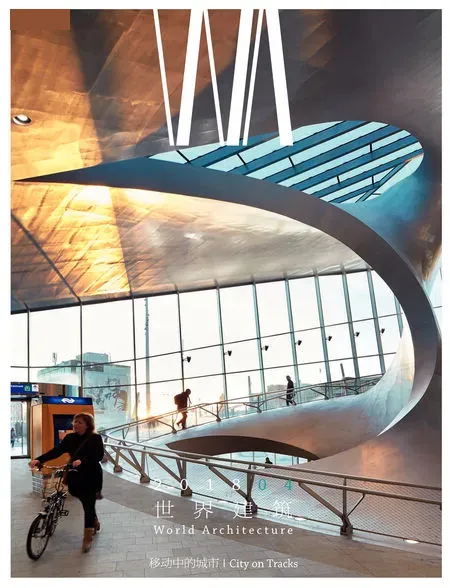

第三個特性是把交通樞紐的空間當成是一種都市景觀進行設計,全然顛覆掉紀念性交通空間的傳統。在紀念性主導的時代,交通樞紐的設計是關于屋頂、柱子、墻體和立面的,而在都市景觀的時代,交通樞紐的設計只有一個優于任何其他表面的關注——我們行走移動的水平面——地面。在阿納姆中心換乘樞紐的設計中,這一關注造就了一個令人興奮的延展與纏繞地面體系,其所能承載的移動與活動類型超乎最初的想像。這可能是源于荷蘭人揮之不去的自行車情結,也可能是源于建筑師對流動延伸空間的鐘情,無論如何,它給予過客以一種類似公園般愜意的移動體驗——在車站里消磨時間,如同在公園里一般?這聽起來真是不壞。

第四個特性要復雜得多,雖然在視覺上它最容易識別,即使在進入樞紐空間前。這個特性就是時下盛行的直接以交通樞紐為基底,在其上進行綜合開發,即TOD,或交通綜合開發。根據不少專業人士的解釋,直接在交通樞紐上進行綜合開發,集結高密度的空間,堆迭復雜的多種功能(包括工作和居住),以及采用垂直發展的類型是最大化利用交通樞紐便利性的靈丹妙藥。東京周邊的高密度區域是這一模式的先行者(多數為東京鐵路公司自行開發),而其顯而易見的固定資產市場吸引力則直接在柏林或深圳的同類建設中得到了發揮。一方面,我們必須承認在最小的城市足跡上建設緊湊的、超高密度的微型城市是一種非常進步的實驗,另一方面,我們也需要認知它的風險。這里的一個重要問題是在某地進行TOD開發的緣起究竟是什么。如果是增長的局域人口的剛性需求,那么這一開發匆庸質疑將是對城市有益的。但如果是僅僅為了獲得最大的市場價值,那么在相應的開發中,軌道交通的進步與革新被過度開發的貪婪所淹沒也不是不可能的。□

參考文獻/References

[1] Chakrabarti, Vishaan. A Country of Cities: A Manifesto for an Urban America. Metropolis Books,2013:14-25.

[2] Tafuri, Manfredo and Dal Co, Francesco. Modern Architecture/2. Electa/Rizzoli, 1976[1986]:258.

Mobility forms a quintessential part of contemporary life. For any modern metropolitan inhabitant, a significant chunk of daily life is spent on some form of public transportation. Everyone may have a different idea on which form of public transportation works the best. But the consensus of twenty-first century urbanists seems to be that the model of hyperdensity connected by rails/light rails is the most desirable and sustainable[1]. It is also common to see the updating of railway and subway infrastructure being the most popular subject of urban renewal projects, both in developed cities and emerging ones. For visitors and inhabitants alike,more often than not, the railway/subway spaces are becoming the de-facto prime identity-giver to metropolises around the world. The sound, smell,touch and vibe of major rail/light rail transit hubs have therefore become definitive experiences and qualities of our urban lives.

Transit hubs are products of urbanisation back to industrialisation times. Just as cities took a long road to eventually put humans in the centre,transit hubs had been for long a realm of technology and efficiency before finally turning into public spaces. 19th Century railway stations were objects of imperial competitions, with excessive pursuit of stone and cast-iron monumentality. Behemoth canopies and gargantuan spaces made the stations more palaces than hubs. Surprisingly, this tradition of monumentality in transit spaces has survived much longer than the imperial states that created them and have extended all the way up to our time. From old world cities to new progressive municipalities,the adoption of monumental transit hubs seemed to be irresistible. In 20th century Moscow, we saw the extravagance of metro stations as underground palaces. In 21st century emerging Chinese cities,we see the grandeur of hi-speed railway stations. In today's New York, we witness yet another manifesto of monumentality in public transportation, albeit in crystal-clear glass and clean white cladding of aluminium alloy, not stone or cast-iron.

Ironically, the making of transportation hubs as public spaces was initiated in a very unlikely political climate. In the 1920s, Mussolini's policies were fixed and started to dominant Italian urban life. In the years that followed, state sponsored projects, mostly in public infrastructure, became the main measure of stimulation to counter economical volatilities. This nevertheless led to major transformation of old urban centres. In the 1933 competition winning, rationalist project for Florence railroad station, the then young architect team led by Michelucci delivered "the advocates of a new architecture promoted a debate that remained well within the limits of discussions as to specific approaches and ways of working"[2]. And the basic quality of this "debate" and "specific approaches"was the integration of the concourse space, no longer elevated from the urban ground, with typical urban services. Though not as big as many of its counterparts today, this did give a new definition to railroad stations (and to all transportation hubs as well), in which the boundary between a station and a public space is crossed-over.

More than eight decades later, we feel reassured to say that currently, transportation hubs are moreand-more taken by default as public spaces. Although there are a few exceptions, most urban transit centres are taking the experience of the people truly seriously. The humanisation of transportation hubs can be identified through four characteristics.

The first the priority given to slow mobility,with expanded surface area serving pedestrians and bicycles. Typologically, most modern stations and transit centres would deliberately weaken the sense of concourses and lounges, while replacing them with indoor plazas, atriums and streets. This strategy is visible in both new stations and renovated old stations, In the central station of Zurich, the entire old station building is emptied to give room to an indoor public open space, not much different from a conventional city market. The fl exibility and vitality of such a typology can only be a plus to the identity of a 21st century international city.

The second is the inclusion of more recreational and public programs. The inclusion of retails, cafes and restaurant is quite conventional. But the inclusion of galleries, gaming parlours, theatres and libraries is rather intriguing, and is more and more common in European stations. The new central station in Delft, definitely inspired by the renown technological university that resides in the town, accommodates serious displays of cutting-edge renewable energy cars. It does seem that modern transportation hubs are getting more and more confident that passengerson-the-move will spend more time inside the station than their normal transit activity requires, and it is exactly this bold assumption and the related designs that makes passengers staying longer in the station,making it a truer public space.

The third is to design the spaces as urban landscapes, overhauling the traditional monumentality idea of stations/transportation hubs. While monumentality would put emphasis on roofs, columns and walls (facades), urban landscape,instead, would pay primary attention to the surface below our feet. In Arnhem Central Transfer Terminal, this attention has resulted in an amazing network of paths and surfaces intertwining more activities than what is imaginable. Partly driven by the Dutch obsession with bicycles, partly driven by the architects' obsession with flux space, this terminal does give a public park-like experience to all its visitors. More time spent in a station equals to more time spent in a park? Not a bad idea at all.

The fourth is a more complicated one, albeit visually rather distinctive. It is the tendency of developing the station or transit centre itself into a mixed-use complex, under the jargon TOD (Transportation Oriented Development).Accommodating higher density, stacking more program (including working and residential),going vertical is said to be the panacea to take full advantage of the easiest mobility access these transportation hubs provided. Pioneered by developments in ultra-dense areas near Tokyo(mostly by railroad companies themselves), this economically attractive option has seen its offspring in cities like Berlin and Shenzhen. While creating a compact, miniaturised, full-f l edged mini city on an extremely small footprint is a very progressive idea,there are caveats though. The first and the foremost one being the question of what drives a TOD. If it is the increasing demand by a growing population,fine. If it is simply the market, then probably all the good about modern rails/light rails would be overshadowed by the greed of overdevelopment.□

——以防城港市為例