Work,Always Work

Rachel Corbett

∷蔣素華 選注

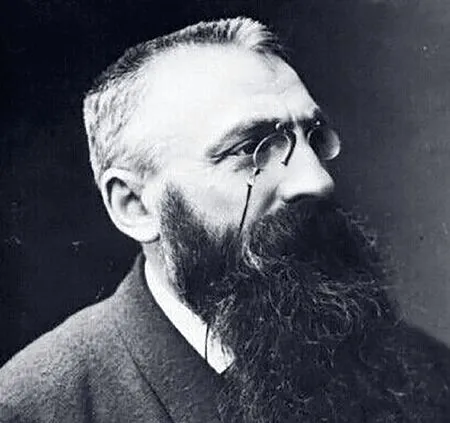

All artists must learn to see,but the imperative(命令,規(guī)則)was literal for young Auguste Rodin.He squinted(瞇眼看)through five years of boarding school before realizing that the obscurities(模糊)on the blackboard were the effects of nearsightness.In stead of gazing blindly ahead,he often turned his attention out the window at a sight too commanding to overlook:the great Cathédral Saint-Pierre in Beauvais1.博韋皮埃爾大教堂,位于法國北部城鎮(zhèn)博韋,建筑始于13世紀(jì),為哥特式風(fēng)格的羅馬天主教堂。,an ancient village in northern France.

To a child,it would have been a monster.Begun in 1225,the Gothic masterpiece was designed to be the tallest cathedral in Europe,with a pyramidal spire(錐體尖塔)teetering(搖搖欲墜 )five hundred feet into the sky.But after two collapses in three centuries,architects finally abandoned the job in 1573.What they left behind was a formidable(令人敬畏的)sight:a house of cards in rock,glass and iron.

Many locals walked by without even noticing the cathedral,or perhaps only half-consciously registering the fact of its enormity(深遠(yuǎn),龐大).But for young Rodin it was an escape from the inscrutable(難以理解的)lessons in front of him and into a vision of endless curiosity.Its religious function did not interest him;it was the stories written on its walls,the mysterious darkness contained within,the lines,arches,shadow and light,all as harmoniously balanced as the human body.It had a long spinal nave(中殿)caged in by a ribbed ceiling,flying buttresses(拱壁)flung out like wings of arms,with a heart-like chamber at the center.The way its stabilizing columns swayed in the gales(大風(fēng))off the English Channel reminded Rodin of the body’s perpetual(不斷的)steadying of itself for equilibrium(平衡).

Although any comprehension of the building’s architectural logic was beyond the boy’s years,by the time he left boarding school in 1853,he understood that the cathedral had been his true education.He would revisit the site again and again over the years“with head raised and thrown back”in awe,studying its surfaces and imagining the secrets within.He joined the faithful in their worship at the cathedral,but not because it was a house of god.It was the form itself,he thought,that ought to drive people to their knees and pray.

羅丹(1840—1917)是舉世公認(rèn)的繼米開朗琪羅之后最偉大的雕塑家。他出生于巴黎,父親是一名警察,為了躲避巴黎的社會動蕩和街頭巷戰(zhàn),父母把他送往法國北部的一個城市上學(xué)。羅丹對學(xué)校的功課沒有多大興趣,卻對窗外那座著名的大教堂產(chǎn)生了極大的興趣。他時常站在風(fēng)中仰望這座建于中世紀(jì)的哥特式教堂,仔細(xì)觀察建筑的結(jié)構(gòu)和細(xì)節(jié),敬畏于它的神圣,驚嘆于它的神奇和完美。這座教堂可謂是羅丹最早的“藝術(shù)啟蒙老師”,對他后來的雕塑藝術(shù)具有決定性的影響。

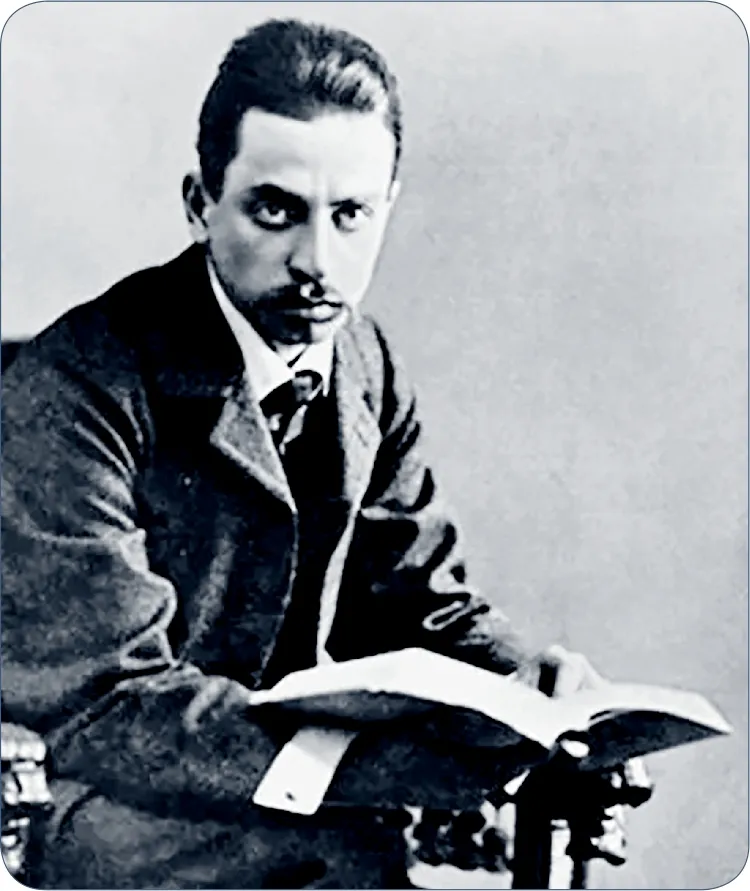

在《你必須改變你的生活:雷納·瑪麗亞·里爾克和奧古斯特·羅丹的故事》(You Must Change Your Life:the Story of Rainer Maria Rilke and Auguste Rodin)一書中,雷切爾·科比特(Rachel Corbett)從當(dāng)時捷克籍著名詩人里爾克與羅丹的結(jié)交和兩人之間曲折的友情這一線索切入,講述了羅丹的藝術(shù)觀和人生觀對里爾克產(chǎn)生的影響,并生動地穿插了他倆以及那一時期活躍在巴黎和歐洲各國的藝術(shù)界、文學(xué)界及學(xué)術(shù)界的一些著名人物之間交往的故事。這期選登的是關(guān)于羅丹的早期藝術(shù)啟蒙。

Fran?ois Auguste René Rodin was born in Paris on November 12,1840.It was a momentous(重要的)year for the future of French art,also marking the births of émile Zola,Odilon Redon and Claude Monet.2.句中提到的依次為埃米爾·左拉(1840—1902),法國小說家,自然主義文學(xué)的代表;奧迪隆·雷東(1840—1916),法國象征主義畫家,超現(xiàn)實主義的先驅(qū);克勞德·莫奈(1840—1926),法國印象派畫家的創(chuàng)始人。But these seeds of theBelle époque(美好年代)would spring from veryarid(荒蕪的),conservative soil.Shaken by both the Industrial and French revolutions,Paris under the monarchy of King Louis-Philippe was the city of depravity(墮落)of poverty depicted inLes Fleurs du MalsandLes Misérables.3.句中提到的作品依次是《惡之花》,法國詩人及作家波德萊爾的著名抒情詩;《悲慘世界》,法國著名作家雨果的長篇小說。New manufacturing jobs attracted thousands of migrant workers,but the city lacked the infrastructure to support them.These newcomers piled into apartments,sharing beds,food and germs.Microbes(細(xì)菌)multiplied in the overflowing sewer system and turned the narrow medieval streets into trenches of disease.As crowds spread cholera(霍亂)and syphilis(梅毒),a wheat shortage sent bread prices soaring and widened the gap between les pauvres(窮人)and the haute bourgeoisie(上層資產(chǎn)階級)to historic proportions.

Auguste was not an impressive student.He skipped classes and received poor grades,particularly in math.When Auguste turned fourteen,his father withdrew him from school.The boy had always enjoyed working with his hands—perhaps trade school would suit him better.

羅丹

Rodin,having just returned to Paris unclear of his interests or ambitions,enrolled at the Petite école in 1854.He did not yet consider himself an artist,and he certainly did not share the exalted(高尚的)views espoused(信奉,贊成)by the Grande école professors,who compared art to religion,language and law.Sculpture was then,and would always be,first and foremost a vocation for Rodin.

Like most of his classmates,Rodin entered with the hopes of studying painting.But because it was cheaper to buy paper and pencils than paint and canvases,he settled on drawing classes instead.It was a hardship that had the fortunate outcome,however,of laying Rodin in the capable hands of Horace Lecoq de Boisbaudran4.霍勒斯·勒科克·布瓦博德朗(1802—1897),法國藝術(shù)家和教師。,the professor who would first correct,and then truly open,Rodin’s eyes.

Lecoq was a squat,soft-faced man,who liked to begin each session with a copying exercise.He believed that keen observation was the indispensable secret all great artists possessed.To master it properly,one had to figure out the essential nature of an object by breaking it down into parts:Copy a straight line from point A to point B,then add in the diagonals(對角線),the arcs(弧線),and so on until the components take form.

One morning,Lecoq placed an object in front of the class,instructing students to copy it onto paper.As he paced the aisles between desks observing their work,he noticed Rodin sketching only its crude outline and then making up the details on his own.Rodin did not strike Lecoq as a lazy student,so he couldn’t understand why he wasn’t completing the task correctly.That’s when it occurred to him that perhaps he boy simply could not see.And so it was in a single exercise that Lecoq identified basic myopia(近視)as the mysterious ailment that had plagued Rodin for more than a decade.

The other transformative revelation from Lecoq’s class took Rodin longer to grasp.The professor often sent students to the Louvre to practice observing the paintings.They were told not to sketch them,but to truly memorize their proportions,patterns and colors.The young Rodin passed his adolescence there on benches seated before works by Titian,Rembrandt and Rubens.5.句中提到的依次為提香(1490—1576),文藝復(fù)興時期的意大利畫家,威尼斯畫派代表人物;倫勃朗(1606—1669),歐洲17世紀(jì)最偉大的畫家之一,也是荷蘭歷史上最偉大的畫家;魯本斯(1577—1640),弗蘭德斯畫家,巴洛克繪畫藝術(shù)的杰出代表,以畫肖像畫和神話題材著稱。They were visions that opened up and expanded inside him like music.He rehearsed every brushstroke in his mind so that he could return home at night,still exalted(欣喜的),and reproduce them from memory.

To some,Lecoq’s emphasis on copying seemed to train students only in the reproduction of other people’s art.It was in many ways a traditional,mathematical approach to form and dimension that was in line with the curriculum at the Grande école.But Lecoq had a different goal in mind.He believed young artists ought to master the fundamentals of form only so that they might one day break them.“Art is essentially individual,”he said.The purpose of the memorization exercises was actually to allow the artists time to acknowledge their reactions to a picture as its properties unfolded to them.Did a gently arched line produce feelings of serenity(平靜)? Did a densely wound shadow evoke(喚起)anxiety? Did certain colors trigger memories? Once artists could name these associations they could then begin to harden their own pooling sensations into external forms of their making.Ultimately,Lecoq’s modern method encouraged artists to draw things not strictly as they appeared,but as they felt and seemed.Emotion and substance became one.

Rodin’s individual style started to emerge at around sixteen.His notebooks from the time reveal an artist already preoccupied with formal continuity and silhouette(側(cè)影,輪廓).In what would become a trademark tendency,he began conjoining the figures in his sketches,linking their bodies together into harmonious groupings that would later evolve into the ring-shaped masterworks ofThe Burghers of Calais6.《加來市民》,羅丹著名雕塑之一。andThe Kiss.

Lecoq’s lessons remained with Rodin long after he graduated and had established his reputation over the years as a sculptor of impressions rather than replications(復(fù)制).He recalled Lecoq’s training decades later,when tasked with modeling a bust(半身像)of Victor Hugo,who refused to pose for an prolonged period of time.Rodin seized glimpses of the man as he passed by in the hall or read in another room,and then sculpted the images later from memory.One looks with the eyes,Lecoq had taught him,but one sees with the heart.

It wasn’t long before Rodin had mastered the curriculum offered at the Petite école.He finished lessons so quickly that the teachers eventually ran out of assignments.He did not care to socialize with his classmates;he wanted only to work.The once exception was his uncommonly supportive friend Léon Fourquet,with whom Rodin shared a love of ponderous(嚴(yán)肅的,沉悶的)debates about the meaning of life and the artist’s role in society.

The teenagers would stroll through the Luxemburg Gardens wondering whether Michelangelo and Raphal ever despaired for recognition as they did.7.句中提到的兩人分別是:米開朗琪羅(1475—1564),意大利文藝復(fù)興時期偉大的繪畫家、雕塑家、建筑師和詩人,文藝復(fù)興時期雕塑藝術(shù)最高峰的代表,與拉斐爾和達(dá)·芬奇并稱為“文藝復(fù)興后三杰”;拉斐爾(1483—1520),意大利文藝復(fù)興時期著名畫家和建筑師。They fantasized about fame,but Fourquet realized early on that this would be Rodin’s fate alone.While Fourquet would go on to master the art of carving marble—a skill Rodin never learned—he always saw an aura(光環(huán))of destiny surrounding Rodin and would later spend several years working for his friend.“You were born for art,while I was born to cut in marble what is germinating(發(fā)芽)in your head—that’s why we shall always be together,”Fourquet once wrote him.

里爾克

By 1857,Rodin had won the school’s top drawing prizes.It seemed he had excelled at every subject except one,and it was the gold standard of artistic achievement:to render(以藝術(shù)形式呈現(xiàn))the human body.To Rodin,the human form was a“walking temple.”To model it in clay would be the closest he would ever come to building a cathedral.The human figure had fascinated Rodin for as long as he could remember.

But since statue commissions went only to the“real”fine artists,trade schools had no reason to offer life drawing classes.If Rodin wanted to study the human form,he would have to transfer to the Grande école.So,in 1857,at the end of his third year at the Petite école,Rodin decided to embark upon the rigorous application.

At the six-day entrance exam,Rodin joined a semicircle of painters and sculptors before a live model each afternoon.According to some accounts,he waved his arms so wildly as he worked that the other students gathered around to watch.Because he was already producing the disproportionate,heavy-limbed figures for which he would become famous,his art proved as unconventional as his gesticulating(打手勢)and it was,in the end,too much for the admissions committee.He passed the drawing exam but failed in sculpture and his application was denied.

Rodin reapplied the following semester,and the semester after that,and was turned away two more times.The rejections sent Rodin into such despair that his father grew worried.He wrote the boy a letter urging him to toughen up.“The day will come when one can say of you as of truly great men—the artist Auguste Rodin is dead,but lives for posterity(子孫,后代),for the future.”Jean-Baptiste(羅丹的父親)knew nothing about art,except that it paid poorly,but he understood the power of perseverance(堅持不懈):“Think about words such as:energy,will,determination.Then you will be victorious.”Rodin eventually coped by turning against the pretentious academy,which he decided was filled with nepotists(任人唯親的人)and guarded by elites who“hold the keys of the Heaven of Arts and close the door to all original talent!”He suspected that his exclusion had to do with his inability to supply letters of recommendation from renowned artists,which other boys had been able to obtain through family connections.

Rodin gave up on art school for good.He continued making his own work,but,denied his“heaven,”he stopped copying the idyllic(田園詩般的)Greek and Roman statues and adopted a kind of aesthetic of survival.From then on,his art was to be grounded in life,in all its unexceptional misery.He began to accentuate(強調(diào))forms that clung desperately to their existence,and those that had been grotesquely(奇異地,荒誕地)defeated by it.