變化的城市景觀、不變的危機與中東新興建筑實踐

科萬茨·科林茨,卡拉·阿拉莫尼/K?van? K?l?n?, Carla Aramouny

龐凌波 譯/Translated by PANG Lingbo

本期專輯從兩個不同而又相互依存的視角概述了從大到小尺度的中東地區當代建筑與城市生活,不僅介紹了杰出建筑項目和城市發展的主要趨勢,還展現了在應對全球挑戰中新興的地方實踐。

與世界其他地區相仿,新自由主義城市政策在塑造中東當代城市景觀方面發揮了重要作用1)[1-2]。在過去的40 年中,公共服務私有化、經濟適用房項目預算縮減、士紳化以及消費主義意識形態的興起占主導地位[3]。由于這個地區的政治沖突、戰爭以及人民的流離失所,我們目睹了難民營和非法聚居地的擴大,以及這些區域基礎設施、清潔水源與衛生設施的不足[4]。同時,標志性高層建筑、濱海旅游投資建設、博物館建筑、豪華別墅區和購物中心已成為中東城市的典型景觀[5]。文化遺產地、濱水區域和公共空間始終承受著巨大的壓力,時而還會致使城市中心的寶貴土地為盈利項目騰退、讓步[6-8]。盡管如迪拜島等大尺度景觀項目創造了新旅游目的地[9],但總體而言,中東城市已躍升為具備全球競爭力的區域中心,以吸引國際資本和投資[10]。正如謝布內姆·于杰爾在她的文章 《繆斯女神的圣殿:論藝術博物館和中東地區》中令人信服地論述的那樣,地標式藝術博物館建筑在塑造文化、城市品牌的雄心勃勃的努力方面起到了重要作用。穆罕默德·加里普爾的文章《重思當代中東的城市景觀》為本刊提供了同樣引人入勝的分析,探討了今天和不久的將來中東地區的規劃師和建筑師所面臨的挑戰。對生態驅動下的、可持續的、注重地方建筑實踐的城市和景觀項目與日俱增的敏感度,預示了這一前景中可能發生的轉變。

好的方面在于,過去20 年同樣見證了自下而上的建筑與城市設計運動的崛起,這些運動是對世界各地新自由主義經濟政策的回應和突破。與大規模的城市規劃干預相比,新興實踐更熱衷于作為空間催化劑,在建筑和社區層面“修復”城市的損傷[11-12]。此外,年輕一代的建筑師和設計專業學生對那些會對地區和整個地球產生負面影響的問題更加敏感,例如環境危機和全球氣候變化。這一點在中東也絕無例外。從人道主義建筑實踐到設計激進主義,青年專家和新銳事務所正在應對我們的城市每天都在面臨的挑戰。卡拉·阿拉莫尼在她的文章《環境、激進主義與設計:黎巴嫩的新興實踐》中雄辯地論述了作為一種基本機制,設計師為應對迫在眉睫的環境與人道主義危機朝激進主義的必要轉向。她總結了黎巴嫩重要的新興實踐,無論這些項目是否有確切的本土或所在地區的委托人,都反映了全球共有的問題;他們批判性的設計方法源于當地環境和場所感。事實上,正如加扎爾·阿巴斯-阿巴格在她那篇引起強烈反響的文章《建筑邊緣的實踐》中總結的那樣,通過對建筑學的批判性反思,新一代設計師實際上正在重新定義實踐本身——正所謂在遠離建筑學的同時更加接近建筑學。

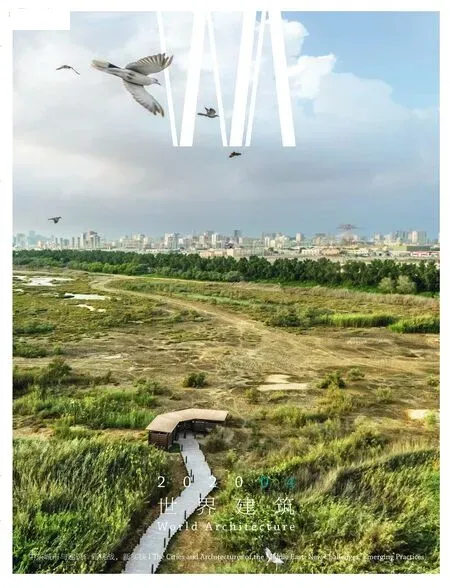

在本期專輯中,項目的選擇除了反映上述積極的轉變,還強調了基于環境和生態敏感對建筑、景觀以及城市干預的理解。一部分項目,如摩洛哥的阿尤恩技術學院、約旦的皇家自然保護學院、土耳其的桑賈克拉爾清真寺,揭示了通過當地材料的運用和精細的形式策略來融入環境的設計方法。另一部分選例,如土耳其的博斯坦利人行橋與日落休息臺、阿聯酋的瓦西特自然保護區游客中心,展現了一種結合自然地形、基礎設施和使用功能的細膩的混合設計方法。

黎巴嫩的尼邁耶旅館改造項目、德黑蘭的埃爾克哈尼住宅樓,以及摩洛哥的瓦盧比利斯博物館同樣反映了利用空間體驗、建筑細部和當地工藝,將建筑與他們的環境置于創造性的對話中的絕妙之處。除了這些體現設計對場所的敏感性的項目之外,其他獲選項目,如黎巴嫩的美國社區學校教學及職工宿舍樓和拱頂住宅,還有科威特的希沙姆·A·阿爾薩格心臟康復中心,則更進一步地將地方性設計置于本土與全球話語之間的交匯點上。

借此,本期專輯試圖闡明中東地區在建筑與城市學領域的多種觀點。通過選例與文章,我們嘗試反思了這一不斷變化的學科領域,特別介紹了建筑與城市設計方面涌現的新方法——這些方法注重本土與生態的敏感性,同時與更宏觀的學科保持聯系,并為其作為全球話語的轉變作出貢獻。□

致謝:在此感謝為本期專輯撰稿的諸位同仁,感謝他們貢獻了精彩的文章和寶貴的評論,同樣感謝受邀刊登作品的建筑事務所,是他們使得本期專輯成為可能。

This special issue offers an overview of contemporary architecture and urbanism in the Middle East from two different yet interdependent angles, moving from the larger to the smaller scale.One deals with prominent architectural projects and dominant trends in urban development and the other with emerging local practices responding to global challenges.

Similar to many other regions around the world, neoliberal urban policies played a major role in shaping the contemporary cityscapes in the Middle East.1)[1-2]The last four decades have been characterised by the privatisation of public services, cuts in the subsidisation of affordable housing programmes, gentrification, and the rise of consumerist ideologies[3].Because of political conflict, wars and displacement in the region, we have witnessed the expansion of refugee camps and informal settlements with insufficient access to infrastructure, clean water and sanitation[4].In the meantime, signature high-rise buildings, coastal tourism investments, museum buildings, fenced-offluxury neighbourhoods, and shopping malls have become a typical sight for Middle Eastern cities[5].Cultural heritage sites, waterfronts and public spaces have been under immense pressure, which at times resulted in the evacuation of valuable areas in city centres to make room for profit generating projects[6-8].While large-scale landscape projects such as the Dubai Islands created new tourism destinations[9], cities in general have been promoted as globally competitive regional centres to attract international capital and investment[10].As ?ebnem Yücel compellingly argues in her essay, "Temples of the Muses: Art Museums and the Middle East",landmark art museum buildings play a significant part in such ambitious cultural, city branding endeavours.Mohammad Gharipour's essay,"Rethinking Urban Landscapes in Contemporary Middle Eastern Cities", contributes to this issue with an equally compelling analysis, deliberating the challenges that face planners and architects in the Middle East today and in the immediate future.Growing sensitivity to ecologically driven,sustainable urban and landscape projects that value vernacular building practices indicate a possible shift in this otherwise bleak picture.

On the brighter side, the last two decades have also witnessed the emergence of bottomup movements in architecture and urban design,formed in response to and through the cracks of neoliberal economic policies in diverse geographies of the world.Emergent practices have been more interested in "healing" the city's broken parts in the architectural and neighbourhood level, as spatial catalysts, than large-scale urban planning interventions[11-12].Moreover, the younger generations of architects and design students are more sensitive to the issues that negatively affect the region and the planet at large, such as the environmental crises and global climate change.And the Middle East is by no means an exception.From humanitarian architectural practices to activism through design, young professionals and new offices are addressing the challenges that our cities experience on a daily basis.Carla Aramouny eloquently discusses in her essay "Environment,Activism, and Design: Emerging Practices in Lebanon", the necessary shift for designers towards activism as a fundamental agency to address dire environmental and humanitarian problems.She reflects on key emergent practices in Lebanon,which, regardless of having a local or regional clientele, are suggestive of a global condition;their critical approach to design is informed by the local environment and sense of place.Indeed,as Ghazal Abbasy-Asbagh concludes in her powerfully evocative essay, "Practice at the Margins of Architecture", by critically reflecting on the architectural discipline, a new wave of designers is in fact redefining the practice itself - moving simultaneously away from and closer to architecture.

Throughout this issue, the selection of projects reflects on the abovementioned positive shifts,and highlights an understanding of architecture,landscape, as well as urban interventions that are contextually grounded and ecologically sensitive.Some projects such as the Technology School of Laayoune in Morocco, the Royal Academy for Nature Conservation in Jordan and the Sancaklar Mosque in Turkey, reveal design approaches that assimilate their environment through local material application and subtle formal methods.Other selected projects,such as the Bostanl? Footbridge & Sunset Lounge in Turkey and the Wasit Nature Reserve Visitor Centre in the UAE, display a sensitive and hybrid approach integrating natural topography, infrastructure, and user programmes.

The Niemeyer Guest House Renovation in Lebanon, the Eilkhaneh Residential Building in Tehran, and the Volubilis Museum in Morocco equally reflect a subtlety in putting buildings and their context in a creative dialogue while capitalising on spatial experiences, architecture details, and local know-how.In addition to projects that reflect on a place driven sensitivity to design, others included in this selection, such as the American Community School Faculty Building and the House of Many Vaults in Lebanon, and the Hisham A.Alsager Cardiac Centre, Kuwait, further position design from the region at an intersection between the local and the global.

This issue thus attempts to shed light on different Middle Eastern perspectives in the architectural and urban spheres.Through the selected work and contributed essays, we seek to reflect on a changing field, and feature emergent approaches to architecture and urban design that focus on local and ecological sensitivities while remaining connected to the larger discipline and contributing to its transformation as a global discourse.□

Acknowledgement: We would like to thank colleagues who have contributed to this issue with their brilliant essays and much valuable comments, as well as the offices who shared their work for publication.

注釋/Note

1)本前言參考了作者科萬茨·科林茨之前發表的文章內容,詳見參考文獻[1]和[2]。/In parts of this editorial preface, K?van? K?l?n?'s earlier work was borrowed.Please see Reference [1] and [2].

參考文獻/References

[1] KILIN? K, GHARIPOUR M.(ed.).Social Housing in the Middle East: Architecture, Urban Development,and Transnational Modernity[M].Bloomington:Indiana University Press, 2019: 1-34.

[2] KILIN? K, KA?AR D.In Pursuit of a European City:Competing Landscapes of Eski?ehir's Riverfront[M]//GHARIPOUR M.Contemporary Urban Landscapes of the Middle East.London, New York: Routledge, 2016:45-66.

[3] KEIL R.Third Way Urbanism: Opportunity or Dead End?[J].Alternatives 25, 2000 (2):247-267.

[4] RADFORD T.Refugee Camps Are the 'Cities of Tomorrow,' Says Humanitarian-Aid Expert[J/OL].dezeen magazine.(2015-11-23).https://www.dezeen.com/2015/11/23/refugee-camps-cities-of-tomorrowkillian-kleinschmidt-interview-humanitarian-aid-expert/

[5] KHAN H-U.A New Paradigm: Global Urbanism and Architecture of Rapidly Developing Countries[J].International Journal of Islamic Architecture 3.1 (March 2014): 5-34.

[6] ABU-HAMDI E.The Jordan Gate Towers of Amman:Surrendering Public Space to Build a Neoliberal Ruin[J].International Journal of Islamic Architecture 5.1 (March 2016): 73-101.

[7] HATICE K.(ed.).?stanbul'da Kentsel Ayr??ma,Mekansal D?nü?ümde Farkl? Boyutlar [Urban Disintegration in Istanbul: Different Dimensions of Spatial Transformation][M].Istanbul: Ba?lam, 2005.

[8] BORA T.(ed.).Milyonluk Manzara: Kentsel D?nü?ümün Resimleri [A View Worthy of a Million Dollars: Images of Urban Transformation][M].Istanbul: Iletisim, 2013.

[9] KHAN H-U.Identity, Globalization and the Contemporary Islamic City[J].International Journal of Islamic Architecture 1.2 (August 2012): 197-216.

[10] KEYDER ? (ed.).Istanbul: Between the Global and the Local[M].Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 1999.

[11] TüRELI I.'Small' Architectures, Walking and Camping in Middle Eastern Cities[J].International Journal of Islamic Architecture 2:1 (2013): 5-38.

[12] AWAN N, SCHNEIDER T, TILL J.Spatial Agency:Other Ways of Doing Architecture[M].London and New York: Routledge, 2011.