建筑學邊緣的實踐

加扎勒·阿巴西-阿斯巴格/Ghazal Abbasy-Asbagh

尚晉 譯/Translated by SHANG Jin

論點

[貝魯特]加扎勒:

“你們實踐的定位是什么?”

[貝魯特]拉法特:

“我工作的一大關注點是將‘虛構’作為一種邏輯體系來運用,而非囿于虛構與非虛構的二元對立。在這個意義上,虛構讓我在以建造(既是文字上的,也是當代藝術中的)世界作為建筑的實踐中,創造出替代文本及‘其他’場景的世界/運動場。”

[ 德黑蘭 ] 納希德:

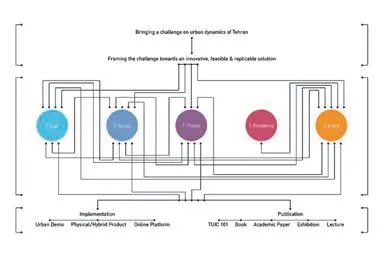

“德黑蘭城市創新中心(TUIC)成立于2016年。其目標是在全球城市創新的整個網絡中,通過在知識生產模式2的框架內知識的生產、交流和施用來創造價值。我們認為教學作為建筑話語、研究和實踐的持續性調節手段,需要在多重性的狀態下去分析,所以并非僅僅局限于官方學術機構框架的構成要素。”

[貝魯特]薩利姆:

“我只是把它稱作建筑,其他的一切都是服務。我提供足以支付房租的服務,并且嘗試去做越來越少的工作,其余的才是建筑。”

[德黑蘭]禮薩:

“美存在于利益相關者的眼中。”

“要通過分析需要得到解答的根本問題,是與建筑項目相關的問題與GDP驅動思維之間的本質關系。因此,所采納的是一種以在空間創造中尋求恰當的建筑解決方案的過程為先、而以這一過程的最終結果或空間產物為后的世界觀。”

推論

建筑先后在康德的先驗和福柯的認知意義上,奠定了使知識、話語和文化的創造成為可能的條件基礎。大致考察一下本期展示的上述建筑師的作品,就會看到一種讓環境超越“建成表達”的愿望。如此一來,這些建筑師首要的挑戰就是,相對于積極地利用環境背景,從“將建筑作為建造的可識別符號的構造愿景”1)[1]角度去設計他們的實踐,并給自身定位。這樣的話,一個難以回答的問題仍十分明顯:什么是建筑?或者說,建筑的實踐需要什么?對于一個數十年來話語都由自主和歷史意識的問題來定義的學科——正是這些問題導致了對現代主義的批判反思——這種轉變(假如我們可以這樣叫它)很可能是健康的,如果不是不可避免的。今天正在興起的各種實踐,包括在中東的那些,都不得不構想出一種全新的實踐模式,并在一個與前幾代人截然不同的領域經營下去。

在一篇1968 年的文章中,漢斯·霍萊因直言道:“一切皆建筑。”2)[2]霍萊因認為傳統的建筑定義是有局限的,而且喪失了效力;環境作為一個整體才是建筑活動的領域。他提出人會從空間上和心理上拓展自身的領域,并由此決定了最廣義的“環境”。這樣,通過身心的拓展,人就“進行了溝通”,而建筑是這種溝通的介質。盡管1968 年的確是全球動蕩的一年,并且那個10 年是“反文化”的10年,霍萊因的論述卻毫無新意可言。它只是擴充一下了雨果的話:“在世界的前6000 年中,建筑一直是人類的偉大手稿。”[3]304在小說《巴黎圣母院》第二章,雨果向他的女性讀者道歉,“若是我們在此停歇片刻,并努力挖掘一下隱藏在領班神父謎一般的話語‘這將把它摧毀’背后的含義,那就是:書將把建筑摧毀。”[3]305在說“紙書”將摧毀“石頭書”時,他確立了建筑作為溝通手段的作用,而它至今一直在為教會和國家效力[3]306。

“眾賢治世接替獨裁統治的歷史刻在了建筑上。因為——在這里我們必須強調——決不能以為建筑只能帶來神廟,只能表達僧侶的神話和象征,只能用象形文字將神秘的《十誡》謄寫到它的石書上。倘若真的如此,那么——鑒于每個人類社會都會迎來一個神圣象征被廢棄的時刻:自由的思想摧枯拉朽,人擺脫了神的仆役,哲學和制度的發展令宗教的面孔瓦解——建筑將無法重現人類思維的這個新階段:它的書頁正面有記載,而背面將一片空白;章節會被刪減;而建筑的巨著也將殘缺不全。然而并非如此……”(《巴黎圣母院》,維克多·雨果,1831)[3]308

如果我們承認建筑是一種溝通的工具,并且在一個大繁榮時期[4]的樂觀及其與環境往往是有害的關系早已過去的時刻,面對全球錯綜復雜的社會經濟和政治挑戰,它能夠創造知識、話語和文化,那么問題就是:在為全球規模的自由市場貿易服務之外,建筑服務的又是什么?而這是否構成了學科范式轉變的基礎?本文將通過在兩座中東城市的新興建筑實踐之間建立對話,嘗試回應這些問題。

雙城記

“我們曾擁有一切,我們卻兩手空空,我們本要直升天堂,我們卻直入地獄——簡而言之,那個時代恰如現在,以至于最喧鬧的權威也堅持認為只能用最高級去描述它,不論這樣是好是壞。”(《雙城記》,查爾斯·狄更斯, 1859)[5]

這兩座城市就是德黑蘭與貝魯特。時間是2019年,全球風云變幻的一年。雖然德黑蘭與貝魯特的大小、人口、地理、政治、經濟和城市形態均不同,卻都是沖突和動亂頻頻。這兩座城市都缺少基本服務設施,污染極其嚴重,交通擁堵;社會經濟分化體現在日常生活的方方面面。

或許今天貝魯特處于一種典型的新自由主義狀態,癱瘓的公共部門完全無法提供基本服務3)[6]。在這個海濱小國的首都,內部宗教和派系對立造成的沖突由于其地緣政治狀況而加劇——它處在一系列相互沖突的區域性和全球性的意識形態、政治和政策潮流的要沖。

在伊朗1979 年革命的40 年后,德黑蘭從山區到沙漠一共住著1200 多萬人。這座城市以天文數字的速度增長,人口從350 萬增長到1200 萬只用了不到20 年,而幾乎沒有任何政府部門的監管。一國之都與世隔絕近40 年。每次政治轉折都使德黑蘭墜入絕望的深淵,并體現在經濟的衰敗上。由這些狀況導致的社會經濟分化表現在兩座城市許許多多不堪言說的離奇的階級差異上。

建筑恰好可以解決這些問題,但同時又受到程序和機制的阻礙,而這長久以來一直限制了它在塑造建成環境中發揮核心作用的能力。今天在這種環境中行進的新興實踐,面對因全球資本流和相互沖突的地緣政治潮流而加劇的愈發嚴酷的社會經濟狀況,不得不在與前幾代人截然不同的領域中構想出一種全新的實踐和經營模式。

成果4)

下面是一個短篇小說、一座建筑、一個建筑教學機構和一條阿拉伯頭巾5)。雖然這些項目之間以及同“建筑作為建造的可識別符號”概念的關聯很弱,但選出的這些項目意在建立一個更寬泛的實踐范圍,使建筑再度成為一種溝通的工具。面對一個完全被自由貿易和市場力量驅動的世界秩序,建筑具有了意識形態的屬性。因此建筑是一種抵抗的手段、一種創造韌性的途徑,能夠在學識的塑造中再度占領它的位置。

拉法特·馬吉祖卜

“對于祖母,每個人都是一個宇宙中的宇宙,其他的每個人和每樣東西都活在那里面。……在她的宇宙中,一切都需要大膽的信仰之躍。現實并沒有真的被分享或表達出來。”

上面的引文出自《灑了香水的花園》。馬吉祖卜將它作為一個短篇小說發表在《前哨》雜志上6)[7]。這段文字成為“他對另類政治的不懈追求、重寫永續小說以及研究新形式社會結構的骨架。”[8]因此這座花園成了一個新的領域,它邀請讀者來到“一個可延展的神秘版的阿拉伯世界,這正在被新一代人的愛和反叛不斷雕琢。”[8]可以說,這種實踐模式相對于“社會圖示”與空間建構的反饋環,能把前一種介質直接轉譯為后者。

Tractate

[Beirut] Ghazal:

"Where do you locate your practice?"

[Beirut] Raafat:

"Major focus of my work is the use of 'fiction'as a logical system, rather than within the fiction vs.non-fiction binary.In that sense, fictions allow me to create worlds / playing fields to text alternative and 'other' scenarios within a process of worldbuilding (both textual and within contemporary art)as architecture."

[Tehran] Nashid:

"Established in 2016 Tehran Urban Innovation Centre (TUIC) aims at creating value across the global network of urban innovation, through producing, exchanging and implementing knowledge within the framework of mode-2 knowledge production.We argue that pedagogy, as a constant moderator of discourse, research and practice, needs to be analysed in a state of multiplicity and thus not just limited to what constitutes the frameworks of official academic institutions."

[Beirut] Salim:

"I just call it architecture, everything else is service.I do enough service to pay the rent and I try to do less and less of it, the rest is architecture."

[Tehran] Reza:

"Beauty is in the eyes of the stakeholder.

The fundamental question to which an analytical response is to be sought, is the substantial relationship between the issues pertaining to an architectural project and a GDP-driven mentality.As such, a world view that prioritises the process of finding a proper architecture solution in spatial production over the end result of the process or the spatial product, is adopted."

Conjecture

Architecture, first in the Kantian apriori and later in the Foucauldian epistemic sense, sets the ground for the condition of possibility of the production of knowledge, discourse, and culture.A brief survey of the work of the architects quoted above and presented herein reveals a desire to engage the environment beyond the "built statement".In doing so, the first and foremost challenge of these architects is designing their practice and positioning themselves in respect to the "tectonic vision of architecture as the legible sign of construction"1)[1]vis-à-vis actively engaging their context.As such, the difficult question remains the obvious one: What is architecture? Or rather,what does the practice of architecture entail? For a discipline whose discourse has for decades been defined by the questions of autonomy and historical consciousness - amounting to critical reflections on modernism - this shift, if we may call it that, is quite possibly healthy, if not inevitable.The emerging practices of today, including those in the Middle East, are forced to envision an entirely new mode of practice and operate in an entirely different domain than the generations that came before them.

In a 1968 essay, Hans Hollein claimed simply:"Everything is Architecture."2)[2]Hollein suggests that traditional definitions of architecture are limited and have lost their validity and that the environment as a whole is the domain of the activity of architecture.He posits that one physically and psychically expands his or her sphere and in doing so determines "environment"in its widest sense.As such, through the expansion of body and mind s/he "communicates", and architecture is the medium of this communication.While 1968 was indeed the year of global revolts and the decade was that of "counterculture,"Hollein's statement was hardly a new one.It was a mere expansion of Hugo's claim that "during the first six thousand years of the world, architecture has been the great manuscript of the human race."[3]304In the second chapter of the novel Hunchback of Notre dame Hugo apologises to his "lady readers … if we halt a moment here and endeavor to unearth the idea hidden under the Archdeacon's enigmatical words: This will destroy That.The Book will destroy the Edifice."[3]305In stating that the "book of paper"will destroy the "book of stone," he establishes the agency of architecture as a tool of communication,one that had thus far been in the service of the church and state[3]306.

"The reign of many masters succeeding the reign of one is written in architecture.For - and this point we must emphasise - it must not be supposed that it is only capable of building temples, of expressing only the sacerdotal myth and symbolism,of transcribing in hieroglyphics on its stone pages the mysterious Tables of the Law.Were this the case, then - seeing that in every human society there comes a moment when the sacred symbol is worn out, and is obliterated by the free thought,when the man breaks away from the priest, when the growth of philosophies and systems eats away the face of religion - architecture would be unable to reproduce this new phase of the human mind: its leaves, written upon the right side, would be blank on the reverse; its work would be cut short; its book incomplete.But that is not the case…"(Victor Hugo,Hunchback of Notredame, 1831)[3]308

If we accept architecture as a tool of communication and its capacity in production of knowledge, discourse,and culture, at a moment well beyond the optimism of the boom era[4]and its often toxic relationship with the environment, facing a plethora of socio-economic and political challenges across the globe, the question is: what is architecture in service of but that of the fee market trade at a global scale? And does this constitute the grounds for a paradigm shift in the discipline? In this paper I seek to respond to these questions by creating a dialogue between emergent architectural practices in two Middle Eastern cities.

The Tale of Two Cities

"We had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way— in short, the period was so far like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only." (Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities, 1859)[5]

The two cities are Tehran and Beirut.The year is 2019, the year of global revolt.While Tehran and Beirut have their differences in size, population,geography, politics, economy, and urban form, they both have had their fair share of conflict and upheaval.Both cities suffer from a lack of basic services, extreme pollution, congestion, and a socio-economic divide that manifests itself in all aspects of daily life.

可汗:阿拉伯文化實踐原型協會

馬吉祖卜寫道,“在寫《灑了香水的花園》的整個過程中逐漸發現,這‘另一個’構建出來的世界需要一個支配的力量、一個組織的實體。因此,可汗協會誕生了。”[9]隨后他將可汗協會注冊為黎巴嫩的非政府組織,正式名稱為“可汗:阿拉伯文化實踐原型協會”。可汗協會在本質上是要將小說激活,使之成為建筑延伸活動的場所;城市規模的項目及政策研究等都植根于作為建筑的寫作活動,從而建立起文字與其他活動之間的反饋環:

“可汗協會在麻省理工學院和拉文施泰因大廈的酒店房間都出自《灑了香水的花園》小說中的房間,它還被臨時嫁接到其他小說中。布魯塞爾的可汗協會是可汗空間的第二次重現,成為一次奢華入侵的時段性表演。它漂浮在以一種特殊的地位存于當世的戲謔、嚴肅和攻擊性的調子之間——去目睹清醒的死亡、移民、排外性立法、聯盟的崩潰和對現下假象的幻滅。”

1《灑了香水的花園》中圖/Image from The Perfumed Garden(圖片提供/Courtesy of The Khan)

德黑蘭城市創新中心(納希德·納比安)

納比安成立德黑蘭城市創新中心的決定在本質上是一個草根運動。它源于一種認識——學術體系是有缺陷的,無法應對極其復雜的城市狀況,并且繁雜的社會經濟因素又使之雪上加霜。它通過尋找工業區或低收入街區等被忽視的城市區來實現這一點。城市生活的數字化層面被作為空間設計的一個新領域[10]。另一個同樣啟迪思想的例子是“探頭座”。據設計師說,“探頭座的關注點是將各種材料、技術和制造技術融合起來去實現一種混合效果,從而拓寬了軟機器人技術的可能性。”[10]

薩利姆·阿勒卡迪

或許最能代表阿勒卡迪作品特點的是一種出奇的清晰,這體現在對極端復雜條件的簡單而巧妙的回應上。阿勒卡迪冷淡的態度和對作品低調的表現是一系列本來很復雜的運行模式的癥狀。這些運行模式體現在一個強有力而又平凡的物體上,它擁有沖破文化界限和顛覆社會準則的潛能。

“K29阿拉伯頭巾002號

時間:2017年

材料/介質:對位芳綸合成纖維(K29芳綸?);配棉線十字繡。

尺寸:1200mm×1200mm

這個項目探索了將芳綸?作為一種防彈和類似飛彈的強力材料的潛力。這段芳綸?從美國偷偷運到黎巴嫩后,被送到位于賽達的艾因赫勒韋難民營的一位婦女家中。隨后她在指導下把這種傳統圖案繡在織物上,并選擇了十字繡來保護芳綸纖維的結構完整性。

這種阿拉伯頭巾裹在頭上后,它的性能由于材料的層疊和編織的多向性得到了提高。在實現這一點的同時,它又在戰場和/或公共空間中延續了一種普遍的象征意義。從形象上看,戴著這個頭巾的人猶如我們都渴望成為的神奇的超級英雄。”[11]

“貝魯特001號

時間:2019年

材料/介質:貝魯特的犀牛5.0軟件制作的3dm格式3D模型

大小:697 MB

在環境、經濟和政治的大災難中,我的貝魯特理發師抱怨說:

“(他們)不讓你活(他們)也不讓你死……”

在這個永不得超脫的煉獄里,當建筑成為一種令人作嘔的暴行時,建筑師要做什么?

當需求——并非渴望——遭到貶抑時,我們還能冒險去相信建筑會成為一劑解藥嗎?我們還能在自己創造出來的亮麗光鮮中安居嗎?我們還能天真地幻想沒有叛逆的變革嗎?還是說叛逆足以催生變革?

貝魯特001號是第一個直接可用的貝魯特3D數字模型。

模型標示出了建筑、道路、橋梁和隧道,并利用建筑師及其團隊可用的簡單方法耗時3年建成。它為今天的公眾提供了一同重新想象我們城市的基本手段。

我們將用它做什么呢?

環保主義者會用它來模擬城市中的微風場類型,并提出新的電力配給方案,以降低非正規電網造成的空氣污染嗎?

激進分子會標示出城市中為發現潛在的抗議場所而非法安裝的2000個閉路電視攝像頭嗎?

或者,制圖人員會把長期禁止公開的城市信息嵌入圖層嗎?

它足夠精確嗎?還是說測繪員應該把它做得更準確,然后再次分享?

……

你會拿它做什么呢?”

2可汗酒店,波士頓/The Khan Hotel, Boston(圖片提供/Courtesy of The Khan)

3可汗酒店,布魯塞爾/The Khan Hotel, Brussels(圖片提供/Courtesy of The Khan)

4德黑蘭城市創新中心組織圖/Tehran Urban Innovation Center Organisation Chart(圖片提供/Courtesy of TUIC)

5探頭座/Poking Seat(圖片提供/Courtesy of TUIC)

Perhaps what characterises Beirut today is an intensely neoliberal condition, in which a paralysed public sector is completely ineffective in providing basic services3)[6].The capital of a small coastal country, the strife created by its internal religious and sectarian divide is exacerbated by its geopolitical condition at the crossroads of a range of regional and global streams of conflicting ideologies,politics, and policies.

Four decades after Iran's 1979 Revolution, Tehran houses over twelve million people stretching from the mountains to the desert.The city has grown at an astronomical rate that took the population from 3.5 million to twelve in less than two decades with minimal oversight from any governing bodies.The capital of a country closed off to the world for nearly four decades,Tehran plummets to despair with every political turn,which finds its manifestation in a failing economy.The socio-economic divide created by these conditions is manifested in a range of uncanny class disparities in both cities that are simply unspeakable.

Architecture finds itself distinctly equipped to address these issues and simultaneously obstructed by procedures and mechanisms that have long limited its capacity to play a central role in shaping the built environment.Operating within these environments, in increasingly grim socio-economic conditions, exacerbated by global flows of capital and conflicting geo-political streams, the emerging practices of today are forced to envision an entirely new mode of practice and operate in an entirely different domain than the generations before them.

Yield4)

Included herein are a novella, a building, an institute for teaching architecture, and a Keffiyeh5).While the connection between these projects and to the notion of "architecture as a legible sign of construction" is tenuous, the range of the projects selected is intended to establish a broadened domain of practice, in which architecture becomes once more a tool for communication.Facing a world order entirely driven by free trade and market forces architecture becomes ideological.Architecture is thus a tool for resistance, for developing resilience, capable of occupying its place once more in shaping the episteme.

Raafat Majzoub

6K29阿拉伯頭巾002號/K29 Keffiyeh 002(攝影/Photo:Marwa Younis)

"To my grandmother, every man is a universe within a universe where every other man and thing lives.[…] In her universe, everything required a bold leap of faith.Reality was not factually shared or communicated."

The quotation above is from "The Perfumed Garden".Majzoub published it in The Outpost Magazine6)[7]as a novella.The text became a"skeleton for an ongoing pursuit of alternative politics, rewriting sustainable fictions, and researching new forms of social architecture."[8]The Garden thus became a new territory; one that invites the reader to "a malleable and mysterious version of the Arab World that is being sculpted by the loves and revolts of a new generation."[8]This mode of practice arguably allows a direct translation of "social diagrams" into spatial constructs vis-à-vis a feedback loop that engages both mediums.

The Khan: The Arab Association for Prototyping Cultural Practices

Majzoub writes that "throughout the process of writing The Perfumed Garden, it became clear that this 'other' constructed world would need a governing force, an entity of organisation.For that reason, The Khan was born."[9]He then proceeded to register the Khan as an NGO in Lebanon by the official name "The Khan: The Arab Association for Prototyping Cultural Practices".The Khan in essence is the activation of fiction as a venue for further acts of architecture; urban scale projects, policy research,etc.all rooted in the act of writing as architecture,thus creating a feedback loop between the text and other activities:

"The Khan's hotel rooms at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Galerie Ravenstein are rooms from The Perfumed Garden's fiction that are temporarily grafted in other fictions.The Khan in Brussels is the second iteration of The Khan spaces,which functioned as a durational performance of luxurious intrusion, floating between the playful,serious and offensive tonalities of being present in the world today as an observer of lucid death,migration, xenophobic legislation, the crumbling of unions and disillusionment with present fictions."

Tehran Urban Innovation Centre (Nashid Nabian)

Nabian's decision to establish the Tehran Urban Innovation Centre is in essence a grass-roots movement that hinges on recognising the deficiencies of an academic system that is unable to respond to an extremely complex urban condition, exacerbated by a multitude of socio-economic factors.It does so by identifying neglected urban zones such as industrial zones or low-income neighbourhoods.The digital layer of urban life is utilised as a new realm for spatial design[10].Another, equally thought-provoking example is the Poking Seat.According to the designers, "The Poking seat expands of possibilities of soft robotics with a focus on merging various material, technical, and fabrication technologies to achieve a hybrid effect."[10]

Salim Al Kadi

Perhaps what most represents Al Kadi's work is the uncanny clarity of a simple yet cunning response to an extremely complex condition.Al Kadi's nonchalant attitude and understated representation of the work is a symptom of an otherwise sophisticated series of operations that manifest themselves in an object so potent, yet so mundane that has the potential to trespass cultural boundaries and subvert social norms.

"K29 Keffiyeh 002

Date: 2017

Materials/Medium: Para-aramid synthetic fiber(K29 Kevlar?); with cotton-thread embroidery in cross-stitch.

Dimensions: 1200mm × 1200mm

This project explores the potential of Kevlar?as a powerful material used to resist bullets and similar flying projectiles.Having been smuggled into Lebanon from the US, the length of Kevlar?was then delivered into the home of a woman in the Ain al-Hilweh Refugee Camp in Saida, who was instructed to embroider this traditional pattern upon the textile, a cross-stitch chosen to preserve the structural integrity of the Kevlar fibres.

Wrapping it around one's head, the Keffiyeh's performance is increased through the layering of material and the multi-directionality of the weave.It does so while maintaining an omnipresent symbolism upon the battlefield and/or in public space.In images,those who wear the Keffiyeh appear as fantastic superheroes we all aspire to be."[11]

"Beirut 001

Date: 2019

Materials/Medium: 3D model of Beirut in 3dm Rhinoceros 5.0 format.

Size: 697 MB

In the midst of an environmental, economic, and political catastrophe, my barber in Beirut complains:

"(They) don't let you live and (they) don't let you die…"

In this state of eternal purgatory what will architects do, when building is a nauseatingly violent act?

When need - not desire - is trivialised, can we still risk believing architecture to be part of the solution?Can we continue to obediently inhabit the pristine renders we produce? Can we still naively imagine change without disobedience? Or that disobedience is enough to bring about change?

ZAV(穆罕默德·禮薩·戈杜西)

德黑蘭擁擠的城市中心的一家工作室被分成許多工作間,一個個項目在其中穿梭——從一步到另一步——這個過程就像工廠里的生產線。戈杜西直言不諱的那句“美存在于利益相關者的眼中”無異于一個口號。對于一家力圖直面嚴峻社會經濟狀況的建筑工作室,這就是其宣言書的綱領。

下面這些文字被打印出來,貼在每個“工作間”的門口:

“ZAV是一個由類型驅動的事務所

現有的類型能夠滿足我們所有的空間需求和渴望嗎?還是說應該去創造新的類型?新創造的類型應當在面對多種多樣的需求和未來不可預見的情況時表現出韌性。

ZAV是應變的(也是靈活的)

審美是追求創造增加值的心理狀態的產物,因此沒有先天的定義。美要由觀察者來判斷,要么是殘缺、不一致的格調,要么是表示莊嚴和完美的。

ZAV是腳踏實地的

建筑可以通過價值的創造,甚至是在實現國家利益這樣的共同利益時滿足個體利益的方式變得豐滿……我們關于促進共同利益實現的標準是:用建筑作為一種動力來提高國內生產總值(GDP)。

ZAV支持手工藝

施工技術和手工藝是至關重要的,因為國內擁有充足的人力資源,而且能從這種對工作優先級的重新評估中獲益。這樣GDP提高了,而靈活、經濟的施工技術以及地方的企業家都會集中在與建筑和創造空間有關的事上。”[12]

亮相霍爾木茲[13]:沖突、色彩與可持續

項目位于霍爾木茲南部,通過為島上本地居民賦能的自下而上的過程,完成了構思、設計和制造。這個原型的設計和建造是以建筑師納迪爾·哈利利的超級土坯房試驗為基礎的。這種施工材料/過程幾乎無需獲取知識,并且使用的是島上清淤出來的資源。

法爾希電影工作室和艾塔姆織毯廠

這兩個項目——一個是原有住宅的翻新,另一個是新建項目——相互之間有一種直接的對話。因為二者都從材料的邏輯中找到了美學線索,而這在意識上是由推動本地經濟的愿望驅動的。

后記

索莫爾認為,在我們使建筑的作用超越“建造的可識別符號”之時,建筑的任務就成為對社會圖示的轉譯。本文介紹的新興實踐的意義在于以建筑實踐作為社會政治和文化問題的直接回應。他們賦予自己的使命不只是闡釋和轉譯社會圖示,還要定義這些圖示。這樣,他們賦予建筑的責任遠遠超越了之前的先鋒派,并在建成環境的塑造中占據了大得多的空間,盡管他們并不一定要積極參與建筑的構造性活動。□

7 貝魯特001號/Beirut 001(圖片提供/Courtesy of Salim Al Kadi)

8.9 亮相霍爾木茲/Presence in Hormoz(圖片提供/Courtesy of Majara Accommodations)

10 法爾希電影工作室/Farsh Film(攝影/Photo: Soroush Majidi)

11 艾塔姆織毯廠/Aytam Carpet Weavers(攝影/Photo:Soroush Majidi)

Beirut 001 is the first readily available digital 3D model of Beirut.

Mapping buildings, roads, bridges, and tunnels,and constructed with the humble means available to the architect and his team over the span of three years,it is offered to the public today as a preliminary tool to collectively re-imagine our city.

What will we do with it?

Will environmentalists use it to simulate micro wind patterns in the city and suggest new electricity rationing schedules to reduce air pollution from the informal power grid?

Will activists map the 2000 CCTV cameras illegally installed in the city to find a potent space of protest?

Or will cartographers inscribe into layers longforbidden urban information?

Is it precise enough? Or should surveyors make it more accurate and share it again?

…

What will you do with it?"

ZAV (Mohammad Reza Ghodoussi)

In a studio located in Tehran's overcrowded city centre compartmentalised into several operation rooms, projects move from room to room - operation to operation - in a process akin to a fabrication line in a factory.Ghodoussi's unapologetic statement"beauty is in the eyes of the stakeholder," is nothing short of a slogan that crystalises a manifesto for an architectural practice that is intent on assertively engaging a dire socio-economic condition.

The following statements are printed and installed at the entry to each "operation room":

"ZAV is a Typologically Driven Practice

Are the existing typologies capable of meeting all our spatial needs and desires, or, should new typologies be invented? The invented types should be the ones that can act resilient in confronting variegated needs and unpredictable future circumstances.

ZAV is Adoptive [and Agile]

Aesthetics are the result of a mentality that is oriented towards production of added value and as such does not have a priori definition.Beauty is to be identified by the beholder, either as incomplete,incoherent decors, or that which signals sublimity and perfection.

ZAV is Practical

Architecture can be informed by creating value and even how individual interests can be satisfied along with achieving common good, i.e.national interest(s)…Our criteria for further deliverance of common good, is improvement of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) with architecture as an actant in this dynamism.

ZAV Embraces Craftsmanship

Construction technology and craftsmanship is of utmost importance, given the abundance of available human resources in the country that can benefit from such re-evaluation of priorities.As such, GDP is improved and agile, economical technologies of construction, as well as local entrepreneurship gain a central focus in matters pertaining to architecture and production of space."[12]

Presence in Hormoz[13]: The Conflictual, the Colourful, and the Sustainable

Located in the Southern province of Hormoz,this project is conceived, designed, and fabricated through bottom-up processes that empower the island's local population.The prototype is designed and constructed based on Architect Nader Khalili's experiment with Super-adobe, a construction material/process that requires very little acquired knowledge and uses resources of the Island grabbed from dredging.

Farsh Film Studio and Aytam Carpet Weavers

The two projects - one the restoration of an existing house, the other a ground-up project - are in direct dialogue with one another, as they both take their aesthetic clues from their material logic,which is ideologically driven by a desire to advance local economy.

Post Script

Somol argues that in a moment that we allow the role of architecture to be expanded beyond "the legible sign of construction", the task of architecture becomes that of translating social diagrams.The significance of the emerging practices featured in this paper is that by engaging in practice of architecture as a direct response to socio-political and cultural issues.They task themselves with more than only interpreting and translating social diagram, but rather defining these diagrams.As such, they expand the task of architecture far beyond that of the avant-gardes that came before them and occupy a much greater space in shaping the built environment, despite the fact that they do not necessarily always actively partake in the tectonic act of architecture.□

注釋/Notes

1)索莫爾將建筑師的作用從維特魯威的“莊嚴”概念拓展到“轉譯社會圖示”上——對比福柯關于機器的社會屬性先于技術屬性的概念。見參考文獻[1]。/Somol expands the role of the architect beyond the Vitruvian notion of "gravitas", to that of"translating social diagrams" vis-à-vis the Foucauldian notion of machines being social before being technical.See Reference [1].

2)這篇文章以《一切皆建筑》為題,用英文發表于參考文獻[2]。/The essay is published in English as"Everything is Architecture." in Reference [2].

3)關于新自由主義城市政策對當代中東城市的塑造,請見參考文獻[6]。/For the neoliberal urban policies shaping contemporary Middle Eastern cities,see Reference [6].

4)換言之,本文闡述的過程的產物。/In other words, the product of the process elaborated on herein.

5)阿拉伯世界里男子戴的圍巾,已經成為巴勒斯坦抵抗組織的代表物。/A scarf worn by men in the Arab world that has become representative of the Palestinian resistance.

6)《前哨》是一部潛力無限的黎巴嫩雜志,一年兩期,見參考文獻[7]。/The Outpost is a magazine of possibilities published twice a year in Lebanon.See Reference [7].

參考文獻/References

[1] SOMOL R E.The Diagrams of Matter[J]//Diagram Works: Data Mechanics for a Topological Age.Architecture New York, 1998 (23): 23-26.

[2] OCKMAN J, EDWARD E.Architecture Culture,1943-1968: A Documentary Anthology[C].New York:Columbia University, Graduate School of Architecture,Planning, and Preservation, 1993.

[3] HUGO V.Volume 1, Book five, Chapter 2[M]//The Hunchback of Notre Dame, 1831.

[4] STIGLITZ J.The Roaring Nineties[J/OL].The Atlantic, 2002.https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2002/10/the-roaringnineties/302604/.

[5] DICKENS C.A Tale of Two Cities[M].1859.

[6] DAHER R F.Uneven Geographies and Neoliberal Urban Transformation in Arab Cities Today[J].International Journal of Islamic Architecture, 2008, 7(1): 29-35.

[7] Folch Studio.The Outpost[J/OL].https://www.folchstudio.com/the-outpost/.

[8] MAJZOUB R.The Perfumed Garden[M/OL].https://www.raafatmajzoub.com/the-perfumedgarden.

[9] MAJZOUB R.Writing as Architecture: Performing Reality until Reality Complies[J].Anti Atlas Journal,2017 (2).

[10] Tehran Urban Innovation Center[EB/OL].http://www.tuic.ir/en/.

[11] AL-KADI S."K29 Keffiyeh 002" [EB/OL].http://www.salimalkadi.com/keffiyeh002.

[12] ZAV Architects [EB/OL].http://www.zavarchitect.com/.

[13] ZAV Architects.Presence in Hormoz | Rong Cultural Center[EB/OL].http://www.zavarchitect.com/?work=presence-in-hormoz-rong-cultural-center.

[14] AL-KADI S."Ghost Building" [EB/OL].http://www.salimalkadi.com/06_ghost-building.