別求新聲于異邦

焦雨菲

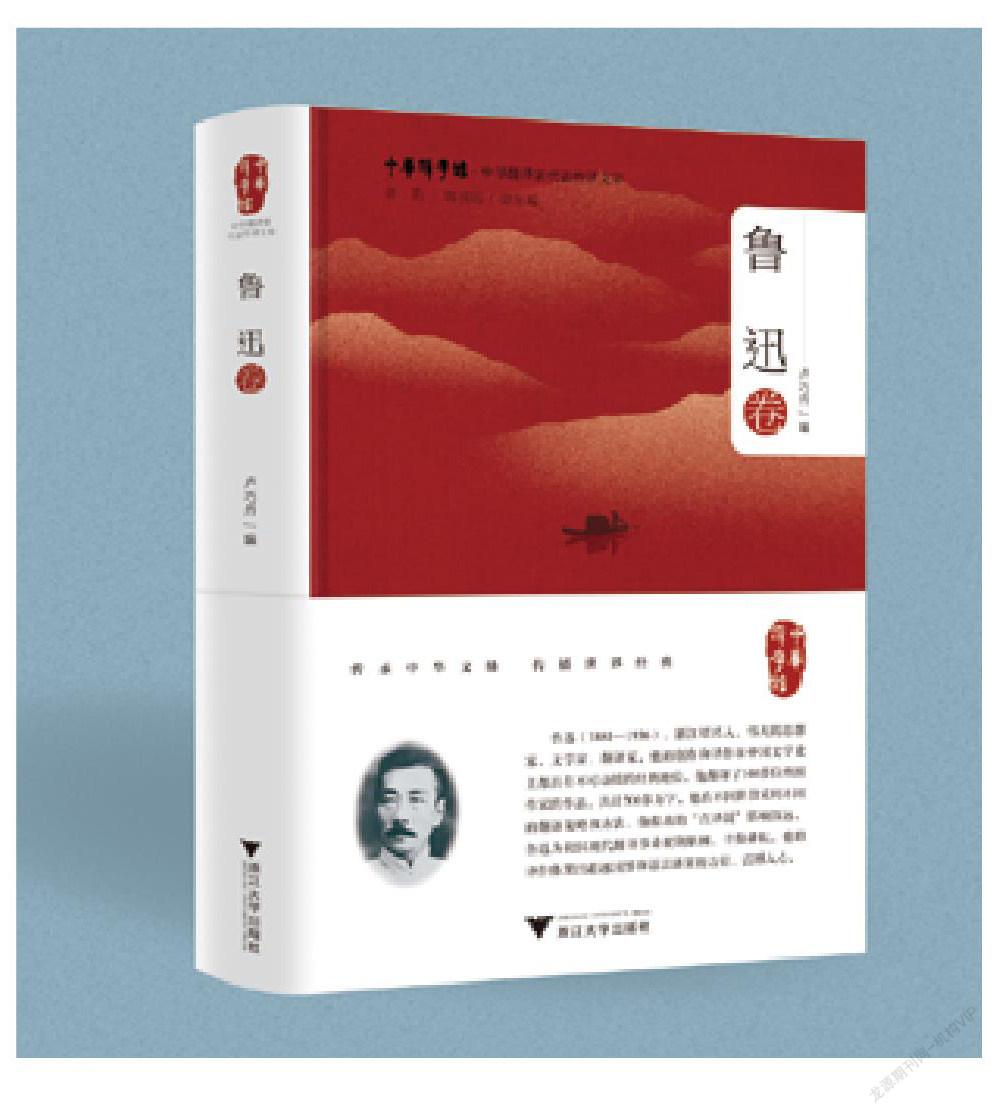

魯迅的文學生涯離不開翻譯。甚至可以說,如果沒有魯迅的翻譯,也就沒有他的創作。《中華翻譯家代表性譯文庫 · 魯迅卷》從福建教育出版社出版的八卷本《魯迅譯文全集》這一目前收錄最全面、校訂最精良的魯迅翻譯著作全集中編選出最具代表性的譯作,全面多樣地展現魯迅翻譯的發展軌跡,供廣大文學愛好者一窺魯迅譯著的風采。

全書共分為四編,從小說、兒童文學、劇本與詩歌、文藝隨筆與文藝理論四個方面詳略得當地介紹了魯迅的代表性譯作,除譯作外還收錄了部分序跋以展示魯迅本人對翻譯的見解。相較于《魯迅譯文全集》這樣的大部頭,《中華翻譯家代表性譯文庫 · 魯迅卷》更適合普通的文學愛好者閱讀。讀罷全書,讀者不僅可以在譯作中感受到魯迅的翻譯思想,還可以借助魯迅本人的翻譯見解更加深入地了解魯迅的翻譯策略、翻譯目的,體悟魯迅譯作經久不衰的原因并重視魯迅翻譯的時代價值。

小說編是全書占篇幅最大的一編,也是放在首要位置的第一編。本編收錄了魯迅自1903年翻譯《月界旅行》至1935年10月翻譯出版《死魂靈》期間具有代表性的小說譯作,基本涵蓋了魯迅翻譯思想演變三個時期的代表性作品。在全書中,本編對魯迅翻譯思想的變化體現得較鮮明,內容也較豐富。

《月界旅行》為魯迅早期翻譯作品,彼時他推崇科幻小說對民風民智的開化啟新作用。這一翻譯傾向主要來源于晚清梁啟超等維新派人士的觀點與想法,即引進西方先進的文明與文化以開闊國民的眼界。與此同時,魯迅此時的翻譯方式延續了晚清林紓等人所倡導的意譯風格,《月界旅行》原書與魯迅所參考的井上勤譯本均為二十八章,魯迅將其編譯為十四回,參用文言,采取了章回體的傳統敘述方式。

及至《域外小說集》,魯迅的翻譯思想發生了很大的轉變。首先,魯迅翻譯早期的選題主要是科幻文學,選材目的是“導中國人群以進行”,后逐漸將目光關注于弱小民族文學,取材目的是“要傳播苦痛的呼聲和激發國人”,取材對象的重心發生了變化。其次,翻譯對象由中長篇小說轉變為在創作手法以及審美趣味上都與中國傳統小說大相徑庭的現代短篇小說,推動了中國小說的現代化發展,使之結合外國文學走向了文藝創新。第三,在翻譯方式上,魯迅拋棄了意譯的方式,轉而采用“硬譯”進行幾乎是鏡像化的對照翻譯,追求極致的“信”來達到對文本的忠實翻譯,甚至可以說是“寧信而不順”。如魯迅譯《羅生門》的最后一句為“家將的蹤跡,并沒有知道的人”就是對日語原文的“硬譯”,它在語序上不符合中文語序,用詞也更貼近日語,難免顯得有些佶屈聱牙。然而魯迅“硬譯”的目的不僅在于輸入新的內容,即引入外國文學中新的內容和思想,更在于輸入新的表現手法、構建新的現代漢語語法體系。在此期間,他的翻譯語言也發生了很大的轉變,從文言文變為白話文,并增加了大量的舶來詞。

在翻譯取材上的不斷變化以及翻譯方式、翻譯語言上的不斷改進使得魯迅譯作先是由近乎是創造的意譯變為鏡像般的硬譯,由“歸化”變為“異化”,而后再逐漸發展為在首先強調信的前提下信、順兼顧。這不僅引領了翻譯理論的發展,也推動了現代漢語、現代文學的進步。

此外本書的編排也十分巧妙——先從魯迅的長篇小說譯作中選取不同時期的知名譯作,然后再將魯迅的經典短篇小說譯作逐一按照出版年代排列。從早期譯作《月界旅行》和晚期譯作《死魂靈》的編選來看。兩者產生了跳躍般的反差感,給人以強烈的沖擊力,表現出魯迅翻譯著作前后風格的大變化,而隨后短篇譯作的編選恰好是對魯迅翻譯思想發展軌跡的補充闡釋。同時,本書輔以細致的題注為普通文學愛好者提供了充足的背景資料,在保證譯文全面、多樣、經典的同時,盡可能多地輔助讀者理解,使讀者讀罷整編后再自行細細思考,更能把握魯迅翻譯思想變化的脈絡,重視魯迅經典譯作經久不衰、歷久彌新的啟示價值。

翻譯與創作是魯迅文學中不可分割的一體兩翼,它們互相影響、共同發展。在中學語文的魯迅專題學習中,我們更多接觸到的是魯迅小說與雜文,對魯迅的譯作知之甚少。其實,魯迅在小說創作中所采取的很多寫作手法都有他譯作的影子,可以說,翻譯是魯迅文學的起點之一。“沒有拿來的,人不能自成為新人,沒有拿來的,文藝不能自成為新文藝”,藉此,魯迅于異邦中求得新聲,由譯介推動創作,放眼世界文學,關注弱小文學,并從中開拓出中國文學和社會發展新的道路。我們因此不僅有機會閱讀《豎琴》《連翹》《復仇的話》等外國文學開闊視野,還可以從更新迭代的本國文藝中汲取振奮人心的力量。翻譯家好比是文化間的橋梁,而魯迅的特殊之處在于他不僅有作為翻譯家的忠實與廣博,更有作為作家的不斷創造與不斷開拓。翻譯求得的異域“新聲”日積月累,帶來了中國文藝的“新生”,也帶來了中國思想的“新生”。

Seeking New Inspirations in Foreign Cultures

By Jiao Yufei

Popularly known as one of the greatest contemporary writers, Lu Xun is also an extraordinary translator. One might say that his literary writings cannot exist without his translations. By reading The Representative Translation Library of Chinese Translators: Lu Xun Volume, not only can readers have a glimpse into Lu Xuns translations, they can also gain a deeper understanding of his translation strategies and purposes.

The book is divided into four parts, including novels, childrens literature, and plays and poems that Lu Xun translated, as well as literary essays and literary theories, and introduces Lu Xuns representative translations and his translation “theories”. In addition, a number of prefaces and epilogues he wrote were also selected to show Lu Xuns views on translation.

Take the “novels” of the book for example, the first and arguably the most important part of the book. Its selections range from Lu Xuns first translated book From the Earth to the Moon (by Jules Verne) to Dead Souls (by Nikolai Gogol). One might find that some of these were translated in classical Chinese (wenyan), while others were done in vernacular Chinese (baihua), a fact that is revealing when it comes to the changes of Lu Xuns translation aims.

Indeed, examining his translated works, we can clearly see several turns during Lu Xuns “career” as a translator. When he first introduced From the Earth to the Moon to the Chinese readers, it was a time when science was held in high regard, as it was believed “science can save the country”, and Lu Xun hoped the introduction of science fiction could help achieve that purpose. This translation trend was mainly derived from the ideas of Liang Qichao (1873-1929) and other reformists of the late Qing dynasty (1616-1911), as they eagerly brought in Western ideas and culture to broaden peoples horizons. Gradually, Lu Xuns focus changed to Japanese and Russian literature, for instance Rashōmon and Dead Souls. Apart from that, his translated works changed from novels and novellas to modern short novels, which were very different from traditional Chinese novels in terms of writing techniques and aesthetic tastes. This encouraged the modernization of Chinese literature and its integration with foreign literature towards more literary innovation.

Besides, Lu Xuns translation style had undergone quite some changes during the process. In the early years, he followed the fashion of free translation advocated by Lin Shu (1852-1924), who made available nearly 200 works of Western literature to a whole generation of Chinese readers, despite not knowing any foreign language. Later, he abandoned this approach, and instead practiced the literal approach, to the extent that the translated works read like a Chinese mirror of the original. Although these works might not flow as smoothly as readers would have preferred, Lu Xun had his intended purposes. By translating these foreign literary works, he was trying to introduce into China not only new ideas and new thoughts from abroad, but also new words, new expressions and new grammar, so as to build a modern Chinese language system. It was during this period that his linguistic choice took a turn, changing from classic Chinese to vernacular Chinese, and his works were filled with loanwords. The emphasis on faithfulness to the source texts promoted the development of translation theories and methods, as well as the progress of modern Chinese language.

The Representative Translation Library of Chinese Translators: Lu Xun Volume provides sufficient background information for the general literature lovers with detailed footnotes, ensuring that the translations are comprehensive, varied and classic while aiding the readers understanding as much as possible. After reading the whole book, the readers will be aware of the sublime value of Lu Xuns translations, rethinking the enduring power of his works in the meantime.

To appreciate Lu Xuns literary career in full, one must look at both his original and translated works, as they influenced and helped develop each other. In fact, Lu Xun learned many a writing skill in his translations and tried to apply them in his literary creations, so it is necessary to attach great importance to his translated works. Now, this volume presents the readers with an opportunity to re-read Lu Xuns representative translations, including the linguistic choices, the translation styles and the translation trends in that historical period.

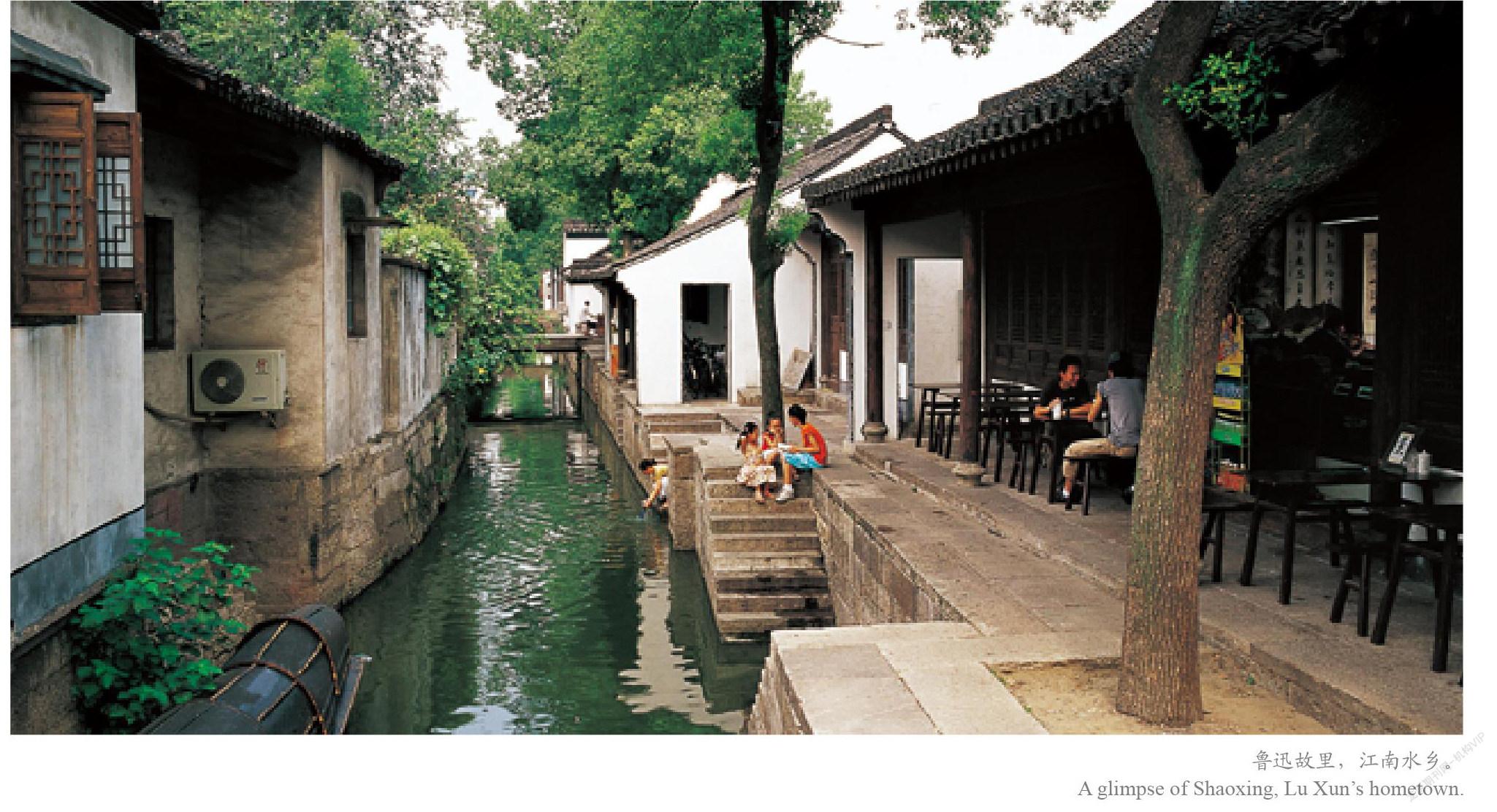

More important, perhaps, were Lu Xuns efforts to build a bridge between translating foreign literature and creating new Chinese literary works. As his coinage of “Grabbism”, or Nalai Zhuyi, showed, it was intended to seek new inspirations from foreign cultures, appropriating anything that works from overseas to create something that fits the local context and blazing a new path for Chinese literature. As an outstanding translator, Lu Xuns uniqueness lies in his broad horizons, as well as his continuous creation and exploration as a writer. The accumulation of foreign “new voices” (xinsheng) by translation has brought about the “new birth” (xinsheng) of the Chinese literature.

Jiao Yufei is an undergraduate student from the Institute of Japanese Language and Culture at School of International Studies, Zhejiang University.