兩親性多糖基膠束改善疏水性功能物質性能的研究進展

李雙紅,葉發銀,雷琳,趙國華,2*

1(西南大學 食品科學學院,重慶, 400715) 2(重慶市特色食品工程技術研究中心, 重慶,400175)

兩親性多糖基膠束改善疏水性功能物質性能的研究進展

李雙紅1,葉發銀1,雷琳1,趙國華1,2*

1(西南大學 食品科學學院,重慶, 400715) 2(重慶市特色食品工程技術研究中心, 重慶,400175)

兩親性多糖往往是親水性多糖適度疏水化改性而獲得的一類低毒、生物相容性和可降解性良好的半合成聚合物,其在水相中能自發聚集組裝成為具有疏水核-親水殼結構的膠束。最近,這類膠束受到食品科學、藥學、生物醫學工程乃至材料學相關科學家的廣泛重視,其研究急劇升溫,且主要集中在利用其改善疏水性物質生物活性方面。論文主要以近5年文獻為基礎,全面綜述了兩親性多糖基膠束在疏水物質分散增溶、靶向遞送、延緩釋放、生物利用度提升及穩定性增強等方面的應用,并在此基礎上對該領域存在的問題及今后的發展方向進行了探討。

兩親性;多糖;自聚集;膠束;疏水活性物質

一些生物活性物質(β-胡蘿卜素、番茄紅素、維生素D3、姜黃素、槲皮素、紫杉醇、喜樹堿和α-生育酚等)或藥物(左旋溶肉瘤素和兩性霉素B等)由于不溶或微溶于水,致使其在生物體內出現分散性差和生物利用率低等缺點,這極大降低了疏水活性物質的臨床應用效能[1-3]。最近發現兩親性分子(表面活性劑)在水相中集聚形成的膠束是解決這一問題的有效工具。兩親性分子在水中達到一定濃度后在疏水相互作用的推動下,分子疏水基團相互締合形成內核并被親水鏈形成的外殼所包圍,進而形成的有序分子集聚體結構稱為膠束。通常將兩親性分子能夠形成膠束的最低濃度稱為其臨界膠束濃度。高于該濃度時聚合物可自發聚集形成膠束,將天然親水性多糖分子經過適度疏水化修飾后可賦予其兩親性,即形成兩親性多糖。該類多糖在水相中能自發集聚形成具有核-殼結構的膠束,其內核由疏水性基團組成而外殼則由親水性糖鏈構成[4]。這一結構特征使該類膠束具有在內核裝載疏水小分子物質的特殊能力,而通過外殼實現其水相分散、生物相容等優點[5]。截至目前,約有上百種兩親性多糖聚合物被合成,對應膠束的理化特性及應用特性,已成為近期食品科學、藥學、生物醫學工程乃至材料學等的重要研究熱點之一。盡管如此,筆者在查閱文獻資料的過程中發現,絕大部分的研究側重于新型多糖聚合物膠束載體的開發研究,而對于其應用特性方面進行系統性梳理的報道少之又少,為了給國內從事該領域的學者提供參考,本文在重點查閱近5年文獻的基礎上,結合國內外研究現狀,對兩親性多糖基膠束在疏水物質分散增溶、靶向遞送、控制釋放、生物利用度提升及穩態化等方面的應用進行綜述。

1 兩親性多糖基膠束對疏水性物質的增溶作用

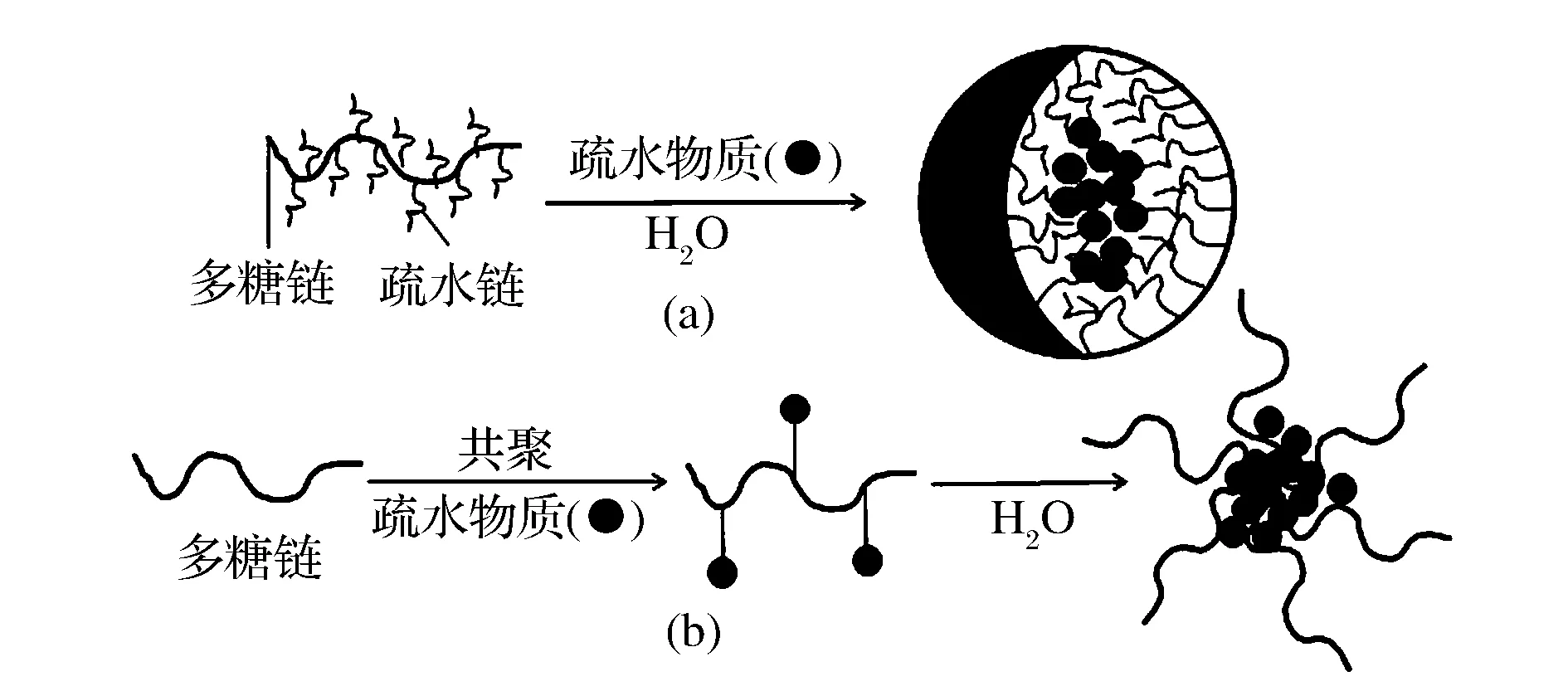

兩親性多糖基膠束對疏水性物質的增溶方式主要分為2種,一種是多糖基膠束通過其內核與目標物質之間的疏水相互作用實現對難溶或不溶性物質增溶[6],其本質仍遵循相似相溶的基本原理。兩親性多糖基膠束對疏水活性物質的增溶過程與常見的反膠束萃取過程十分相似,是被增溶物質從固相(不溶)到液相(極低濃度)再到膠束內相(高濃度富集)的定向傳質過程(圖1-a)。第二種方式是通過共聚[7-8](如酯化反應等)將待增溶的目標物質直接連接到多糖鏈上形成兩親性多糖聚合物,該聚合物在水溶液中自聚集將目標物質以內核形式載入膠束中,由此達到難溶物質在水相中的分散(圖1-b)。增溶過程中常用的方法有薄膜水化法[2]、微相分離法[6]、透析法[9]、水包油法[10]以及乳液溶劑蒸發法[11]等。對增溶效果的評價常以特定濃度的兩親性多糖膠束溶液,荷載目標物質的含量來表示。除增溶方法之外,多糖聚合物的臨界膠束濃度、疏水基團的取代度和疏水性能以及環境參數(時間、溫度、攪拌強度)等都是影響增溶效果的重要因素。表1給出了兩親性多糖基膠束增溶疏水性物質的一些案例。

圖1 兩親性多糖基膠束增溶疏水性物質的主要方式Fig.1 The main ways of amphiphilic polysaccharide-based micelles in solubilizing hydrophobic compounds

2 兩親性多糖基膠束對疏水性物質的靶向遞送作用

生物活性物質只有能抵達特定的器官或細胞才能發揮其特定的生物活性。但對大多數生物活性物質來說,被吸收進入機體后隨著血液循環分布到全身。這不僅影響其生物活性發揮,且易造成正常組織細胞損傷,引發系統毒性[5]。因此,生物活性物質的靶向遞送具有十分重要的意義。根據靶向機制,可分為組織特異性靶向與環境響應性靶向。

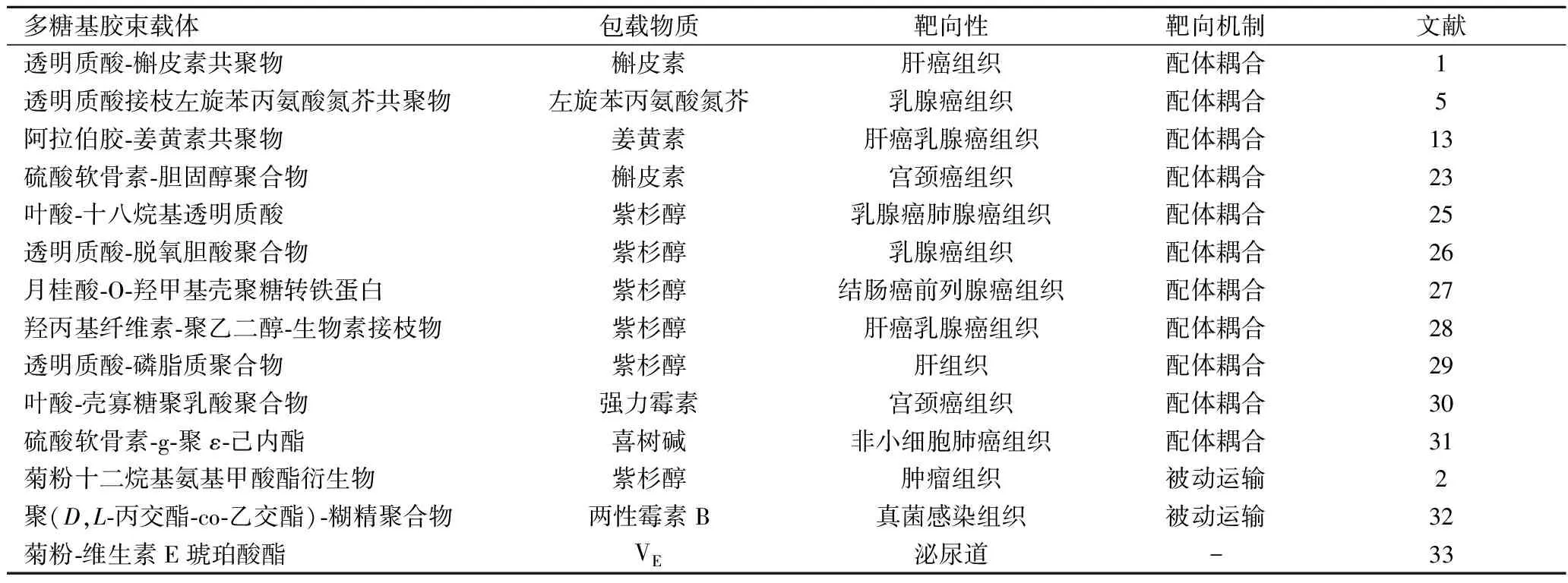

組織特異性靶向又可分為被動靶向和配體耦合靶向。被動靶向主要依賴于靶向組織的高通透性和滯留效應以及兩親性多糖基膠束的尺寸[17]。腫瘤組織血管壁的孔徑一般為幾百納米到幾微米,明顯大于正常組織血管壁孔徑(2~6 nm),這為腫瘤組織吸收和滯留大分子物質或顆粒提供了通道[18],從而生物活性物質被動實現靶向遞送。配體耦合靶向是指在膠束載體上連接能特異性識別腫瘤表面過表達抗原物質的配體,這些配體與目標位點特異性結合,從而使藥物載體在腫瘤組織中選擇性積累。常用的配體包括透明質酸、硫酸軟骨素、葉酸、β-D-半乳糖殘基、生長激素抑制素、轉鐵蛋白、生物素、α2-糖蛋白及表皮生長因子等[19]。顯而易見,不同配體具有不同的靶向性,應根據具體靶向組織選擇使用配體。表2給出了一些多糖基膠束載體靶向運輸的應用案例。

注:增溶效果以水中溶解度→膠束中溶解度表示。

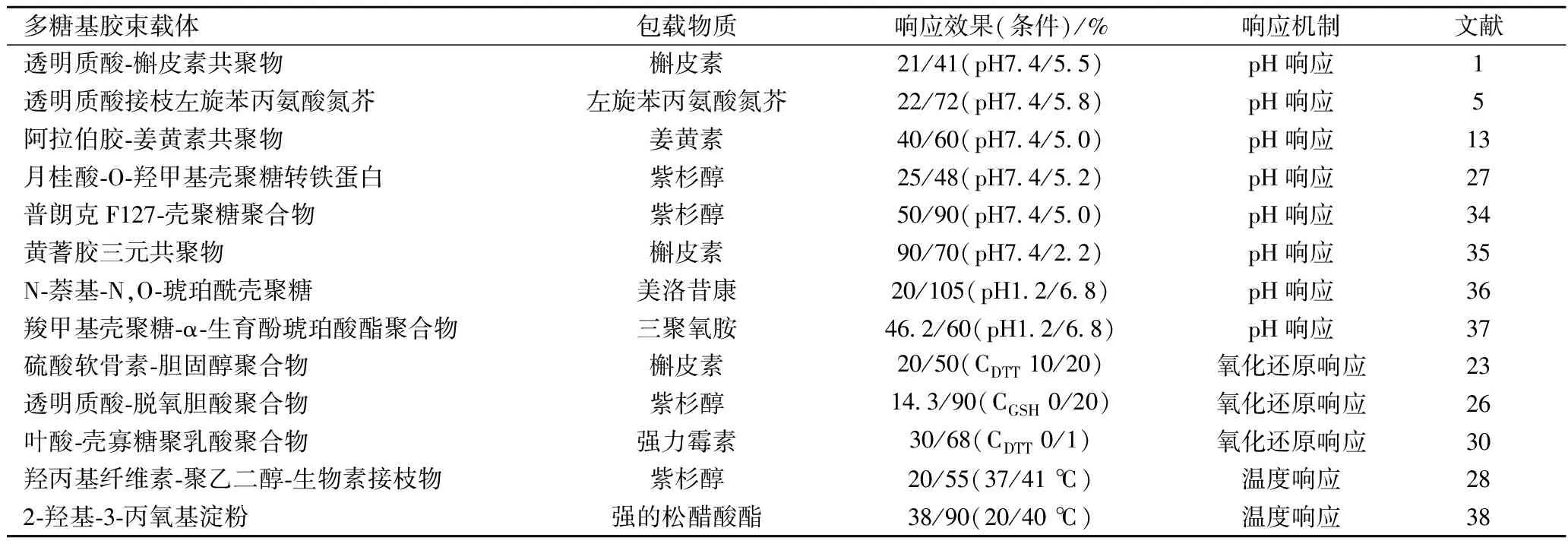

環境響應性靶向主要是根據靶向部位特定的生理環境條件設計的,如常見的pH響應性靶向、氧化還原響應性靶向和溫度響應性靶向。pH響應性靶向的基本原理是人體正常組織環境的pH值(7.4)明顯高于病變部位(如腫瘤細胞外pH值為6.8左右,細胞核內體則為5.5~6.5)[20]。當含有酸可降解基團的多糖基膠束接觸腫瘤組織時,其酸可降解基團發生質子化或解離,導致膠束結構松散甚至解體并釋放活性物質[21-22]。氧化還原響應性靶向常常在多糖基膠束中引入二硫鍵而得以實現。其基本原理為人體正常細胞內谷胱甘肽的含量(2~10 mmol/L)要顯著低于病變組織(如腫瘤細胞中谷胱甘肽的含量約為正常組織中的4倍)。當含有二硫鍵的多糖基膠束接觸腫瘤組織時,在高濃度谷胱甘肽的還原作用下,二硫鍵被打開,導致膠束結構松散甚至解體并釋放活性物質[23]。溫度響應性靶向依據病變部位的溫度高于正常生理溫度(>37 ℃),一旦環境溫度高于熱敏性膠束載體的低臨界溶解溫度,載體發生相變迫使聚合物鏈崩解,加速內容物釋放[24]。表3給出了一些多糖基膠束載體環境響應性靶向的應用案例。

表2 兩親性多糖基膠束載體對疏水性物質的組織特異性靶向應用案例

表3 兩親性多糖基膠束載體對疏水性物質環境響應性靶向應用案列

注:1. 響應效果:載體膠束對不同響應環境的敏感程度以包載物質釋放量的百分數表示;2.CGSH:谷胱甘肽濃度;CDTT:二硫蘇糖醇濃度。

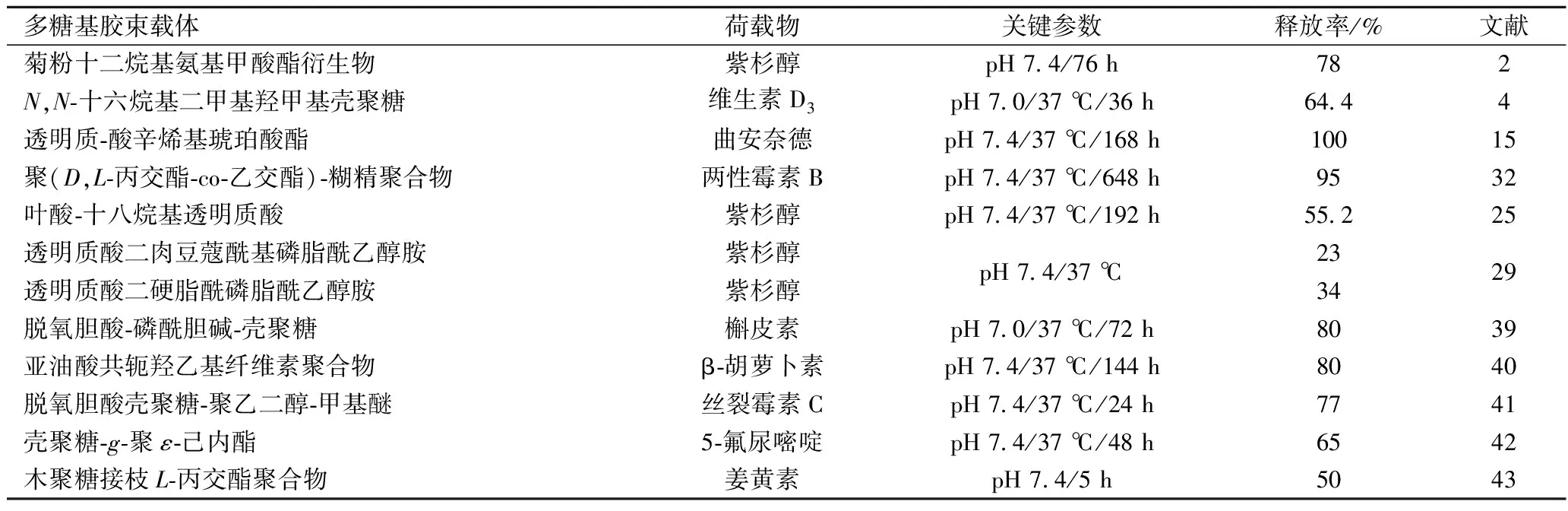

3 兩親性多糖基膠束對疏水性物質的緩釋作用

活性制劑以口服或者靜脈注射的方式進入人體,在組織或血液中富集短時間內濃度達到高峰并被機體快速清除,這直接導致活性物質在組織或血液中維持有效濃度的時間過短,造成浪費[29]。多糖基聚合物膠束的疏水基團與活性成分之間存在相互作用,可延長制劑釋放時間并改善治療效果。活性成分釋放率通常以膠束在特定體系(緩沖溶液、模擬胃液、模擬腸液等)中保溫后,漏出的疏水物質質量百分比表示[23]。疏水內核材料的種類、膠束的降解能力、活性制劑的含量及膠束疏水區域與包載物質之間的親和力的強弱等因素影響活性制劑釋放率[19],具體作用結果見表4。

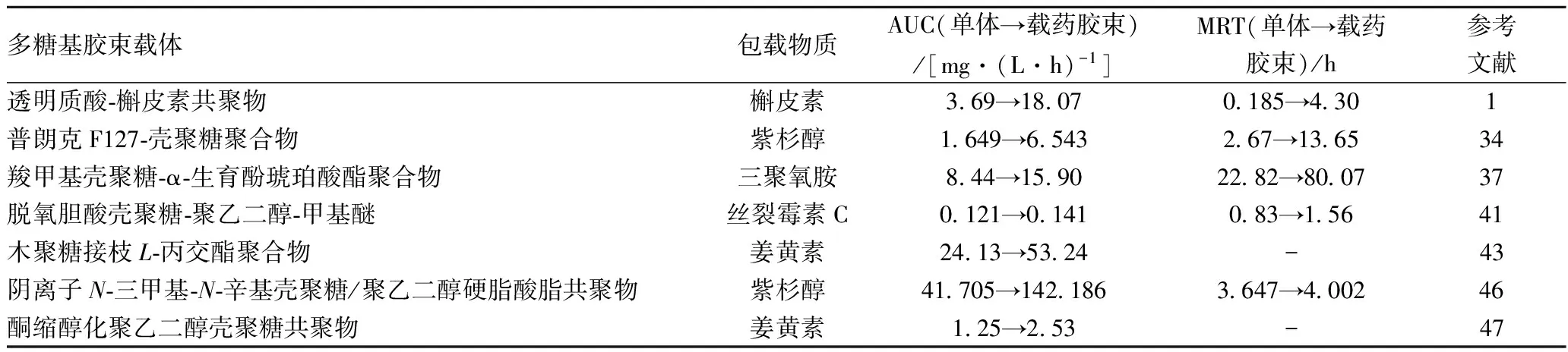

4 兩親性多糖基膠束提高疏水性物質的生物利用度

活性物質自身的強電荷、高分子質量也是限制其臨床應用的重要因素之一[44]。正如前所述,兩親性多糖基膠束特殊的結構將該類物質包裹其中,能大幅度提升其生物利用價值。 常用于衡量活性物質生物利用度的參數包括藥-時量曲線下面積(AUC)、平均滯留時間(MRT)等,AUC也代表生物活性成分進入全身血液循環的相對量,MRT是活性物質在血漿中總保留時間的平均值,AUC和MRT的值越大表示生物活性物質的生理有效性越高[45],具體案例見表5。研究發現[1],利用槲皮素單體及透明質酸-槲皮素共聚物載藥膠束分別對大鼠進行體內藥物動力學試驗,得到了兩者的AUC(3.69→18.07 mg/(L·h))和MRT(0.185→4.30 h)值,表明聚合物膠束可以提高單體藥物的生物利用率。此外,半數抑制濃度(IC50)指用藥后活細胞數量減少一半時所需的藥物濃度,能間接反應活性物質的利用程度,該值越小表示活性物質的效能越大。表6給出了兩親性多糖基膠束載體降低疏水物質IC50值的案例。

表4 兩親性多糖基膠束載體對疏水性物質緩釋作用案例

表5 兩親性多糖基膠束載體對疏水物質AUC和MRT的影響案例

表6 兩親性多糖基膠束載體降低疏水物質半數抑制濃度(IC50)的應用案例

5 兩親性多糖基膠束增強疏水物質的穩定性

某些活性成分的穩定性差,容易隨著生理環境pH值的改變而發生降解反應,嚴重影響其臨床療效。列如:姜黃素在中性或偏堿性環境中快速水解成阿魏酰甲烷、香草酸和阿魏酸等小分子片段物[48]。兩親性多糖基聚合物膠束的核-殼結構有效的避免了活性成分直接與外界環境接觸,顯著提高其穩定性。SARIKA[13]等發現在中性環境中(pH 7.4),37 ℃培育5 h后姜黃素-阿拉伯膠共聚物膠束(GA-Cur)的吸光度值變化不明顯而游離姜黃素25 min時就全部降解。而在酸性條件下(pH 4.0~6.0),游離姜黃素穩定性明顯提升,但仍顯著低于GA-Cur。同樣,與海藻酸或透明質酸共聚形成膠束后也能大幅度提升姜黃素在生理環境中的穩定性[7,14]。β-胡蘿卜素結構中含有共軛多烯鏈和不飽和鍵,對光、熱、氧氣敏感,易發生降解。將β-胡蘿卜素(β-C)包埋于幾丁質-聚乳酸接枝共聚物膠束中分別在4 ℃和25 ℃下保存15 d后,檢測發現其保留率分別達到95.45%和91.85%,表明該聚合物膠束載體能明顯提高β-C的穩定性[6]。此外,利用多糖基膠束作為載體提高紫杉醇在運載過程中理化穩定性的研究也有報道[36]。

6 小結與展望

兩親性多糖基膠束具有生物可降解性和良好的生物相容性,被廣泛應用于活性物質運載體系,但其應用過程中仍存在諸多問題:(1) 多糖基外殼與包載的藥物活性成分之間是否會發生相互作用并改變了活性成分的化學性質尚不清楚;(2) 多糖本身具有特殊的功能作用如:透明質酸、菊粉、殼聚糖等,作為運載體系與活性成分之間是否存在協同作用或抑制作用尚不明確;(3) 多糖基膠束仍存在裝載量低、包封率差等問題,為了提高膠束載體的穩定性,疏水內核與親水外殼之間的交聯過于緊密造成膠束內的物質釋放受到束縛,探究膠束疏水-親水片段之間的交聯形式仍需深入;(4)口服利用率也是多糖基膠束難于克服的問題之一,極端的胃腸環境對膠束載體的穩定性提出了較高要求,有必要繼續尋找無毒、可降解且穩定性好的載體材料。此外,多糖基膠束的應用主要集中在藥物運載體系方面,尤其是抗癌藥物的傳輸研究諸多,而其他方面的研究相對較少。所以未來結合醫藥、食品、化工等多領域的需求設計、開發多功能型多糖基膠束必將擁有廣闊的發展前景和巨大的經濟效益。

[1] PANG Xin, LU Zhen, DU Hong-Liang, et al. Hyaluronic acid-quercetin conjugate micelles: Synthesis, characterization, in vitro and in vivo evaluation[J]. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces, 2014, 123: 778-786.

[2] MULEY P, KUMAR S, KOURATI F E, et al. Hydrophobically modified inulin as an amphiphilic carbohydrate polymer for micellar delivery of paclitaxel for intravenous route[J]. International Journal of Pharmaceutics, 2016, 500(1-2): 32-41.

[3] YU Hai-long, HUANG Qing-rong. Enhanced in vitro anti-cancer activity of curcumin encapsulated in hydrophobically modified starch[J]. Food Chemistry, 2010, 119(2): 669-674.

[4] LI Wen-jian, PENG Hai-long, NING Fang-jian, et al. Amphiphilic chitosan derivative-based core-shell micelles: synthesis, characterisation and properties for sustained release of vitamin D3[J]. Food Chemistry, 2014, 152(2): 307-315.

[5] XU Hai-xing, HE Jing-bo, ZHANG Yu, et al. Synthesis and in vitro evaluation of a hyaluronic acid-quantum dots-melphalan conjugate[J]. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2015, 121: 132-139.

[6] GE Wen-jiao, LI Dong, CHEN Mei-wan, et al. Characterization and antioxidant activity of β-carotene loaded chitosan-graft-poly(lactide) nanomicelles[J]. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2015, 117: 169-176.

[7] MANJU S, SREENIVASAN K. Conjugation of curcumin onto hyaluronic acid enhances its aqueous solubility and stability[J]. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, 2011, 359(1): 318-325.

[8] LI Jing-lei, SHIN G H, CHEN Xi-guang, et al. Modified curcumin with hyaluronic acid: combination of pro-drug and nano-micelle strategy to address the curcumin challenge[J]. Food Research International, 2015, 69: 202-208.

[9] YAO Zhong, ZHANG Can, PING Qin-eng, et al. A series of novel chitosan derivatives: Synthesis, characterization and micellar solubilization of paclitaxel[J]. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2007, 68(4): 781-792.

[10] YU Jing-mou, XIE Xin, ZHENG Mei-rong, et al. Fabrication and characterization of nuclear localization signal-conjugated glycol chitosan micelles for improving the nuclear delivery of doxorubicin[J]. International Journal of Nanomedicine. 2012, 7: 5 079-5 090.

[11] PRIYADARSINI R V, MURUGAN R S, MAITREYI S, et al. The flavonoid quercetin induces cell cycle arrest and mitochondria-mediated apoptosis in human cervical cancer (HeLa) cells through p53 induction and NF-κB inhibition[J]. European Journal of Pharmacology, 2010, 649(1-3): 84-91.

[12] LIU Jia, LI Jing, MA Ya-qing, et al. Synthesis, characterization, and aqueous self-assembly of octenylsuccinate oat β-glucan.[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2013, 61(51): 12 683-12 691.

[13] SARIKA P R, JAMES N R, KUMAR A P R, et al. Gum arabic-curcumin conjugate micelles with enhanced loading for curcumin delivery to hepatocarcinoma cells[J]. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2015, 134: 167-174.

[14] DEY S, SREENIVASAN K. Conjugation of curcumin onto alginate enhances aqueous solubility and stability of curcumin[J]. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2014, 99(1): 499-507.

[15] MAYOL L, BIONDI M, RUSSO L, et al. Amphiphilic hyaluronic acid derivatives toward the design of micelles for the sustained delivery of hydrophobic drugs[J]. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2014, 102: 110-116.

[16] MA Ya-qin, LIU Ja, YE Fa-yin, et al. Solubilization of β-carotene with oat β-glucan octenylsuccinate micelles and their freeze-thaw, thermal and storage stability[J]. LWT-Food Science and Technology, 2015, 65: 845-851.

[17] LEBOUILLE J G, LEERMAKERS F A, COHNESTUART M A, et al. Design of block-copolymer-based micelles for active and passive targeting.[J]. Physical.Review E, 2016, 94(4):1-15.

[18] MATSUMURA Y, MAEDA H. A new concept for macromolecular therapeutics in cancer chemotherapy: mechanism of tumoritropic accumulation of proteins and the antitumor agent smancs[J]. Cancer Research, 1986, 46(1): 6 387-6 392.

[19] KEDAR U, PHUTANE P, SHIDHAVE S, et al. Advances in polymeric micelles for drug delivery and tumor targeting[J]. Nanomedicine Nanotechnology Biology & Medicine, 2010, 6(6):714-729.

[20] GUO Xing, SHI Chun-li, WANG Jie, et al. pH-triggered intracellular release from actively targeting polymer micelles[J]. Biomaterials, 2013, 34(18): 4 544-4 554.

[21] SUDIMACK J, LEE R J. Targeted drug delivery via the folate receptor[J]. Advanced drug delivery reviews, 2000, 41(2): 147-162.

[22] FRECHET J M J, GILLIES E R. Development of acid-sensitive copolymer micelles for drug delivery[J]. Pure and Applied Chemistry, 2004, 76(7-8): 1 295-1 307.

[23] YU Chuan-ming, GAO Chun-mei, Lü Shao-yu, et al. Redox-responsive shell-sheddable micelles self-assembled from amphiphilic chondroitin sulfate-cholesterol conjugates for triggered intracellular drug release[J]. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2013, 228: 290-299.

[24] SHAO Peng-yu, WANG Bo-chu, WANG Ya-zhou, et al. The application of thermosensitive nanocarriers in controlled drug delivery[J]. Journal of Nanomaterials, 2011, 2011(1687-4110): 99-110.

[25] LIU Yan-hua, SUN Jin, GAO Wen, et al. Dual targeting folate-conjugated hyaluronic acid polymeric micelles for paclitaxel delivery[J]. International Journal of Pharmaceutics, 2011, 421(1): 160-169.

[26] LI Jing, HUO Mei-rong, WANG Jing, et al. Redox-sensitive micelles self-assembled from amphiphilic hyaluronic acid-deoxycholic acid conjugates for targeted intracellular delivery of paclitaxel[J]. Biomaterials, 2012, 33(7): 2 310-2 320.

[27] JOUNG N, SEONG P, TAE H K, et al. Encapsulation of paclitaxel into lauric acid-o-carboxymethyl chitosan-transferrin micelles for hydrophobic drug delivery and site-specific targeted delivery[J]. International Journal of Pharmaceutics, 2013, 457(1): 124-135.

[28] BAGHERI M, SHATERI S, NIKNEJAD H, et al. Thermosensitive biotinylated hydroxypropyl cellulose-based polymer micelles as a nano-carrier for cancer-targeted drug delivery[J]. Journal of Polymer Research, 2014, 21(10): 1-15.

[29] SAADAT E, AMINI M, KHOSHAYAND M R, et al. Synthesis and optimization of a novel polymeric micelle based on hyaluronic acid and phospholipids for delivery of paclitaxel, in vitro and in-vivo evaluation[J]. International Journal of Pharmaceutics, 2014, 475(1-2): 163-173.

[30] YANG Qing-lai, HE Chang-yu, XU Yu-hong, et al. Chitosan oligosaccharide copolymer micelles with double disulphide linkage in the backbone associated by H-bonding duplexes for targeted intracellular drug delivery[J]. Polymer Chemistry, 2015, 6(9): 1 454-1 464.

[31] LIU Yu-sheng, CHIU Chien-chih, CHEN Hsuan-ying, et al. Preparation of chondroitin sulfate-g-poly(ε-caprolactone) copolymers as acd44-targeted vehicle for enhanced intracellular uptake[J]. Molecular Pharmaceutics, 2014, 11(4): 1 164-1 175.

[32] CHOI K C, BANG J Y, KIM P I, et al. Amphotericin B-incorporated polymeric micelles composed of poly(d,l-lactide-co-glycolide)/dextran graft copolymer[J]. International Journal of Pharmaceutics, 2008, 355(1-2): 224-229.

[33] MANDRACCHIA D, TRIPODO G, LATROFA A, et al. Amphiphilic inulin-d-α-tocopherol succinate (INVITE) bioconjugates for biomedical applications[J]. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2014, 103: 46-54.

[34] MA Ya-kun, FAN Xiao-hui, LI Ling-bing. pH-sensitive polymeric micelles formed by doxorubicin conjugated prodrugs for co-delivery of doxorubicin and paclitaxel[J]. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2016, 137: 19-29.

[35] HEMMATI K, GHAEMY M. Synthesis of new thermo/pH sensitive drug delivery systems based on tragacanth gum polysaccharide[J]. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2016, 87: 415-425.

[36] WORAPHATPHADUNG T, SAIOMSANG W, GONIL P, et al. Synthesis and characterization of pH-responsive n-naphthyl-n,o-succinyl chitosan micelles for oral meloxicam delivery[J]. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2015, 121: 99-106.

[37] JENA S K, SANGAMWAR A T. Polymeric micelles of amphiphilic graft copolymer of α-tocopherol succinate-g-carboxymethyl chitosan for tamoxifen delivery: synthesis, characterization and in vivo pharmacokinetic study[J]. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2016, 151: 1 162-1 174.

[38] JU Ben-zhi, YAN Dong-mao, ZHANG Shu-fen. Micelles self-assembled from thermoresponsive 2-hydroxy-3-butoxypropyl starches for drug delivery[J]. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2012, 87(2): 1 404-1 409.

[39] WU Min-ming, GUO Kai, DONG Hong-wei, et al. In vitro drug release and biological evaluation of biomimetic polymeric micelles self-assembled from amphiphilic deoxycholic acid-phosphorylcholine-chitosan conjugate[J]. Materials Science and Engineering C, 2014, 45: 162-169.

[40] YANG Yang, GUO Yan-zhu, SUN Run-cang, et al. Self-assembly and β-carotene loading capacity of hydroxyethyl cellulose-graft-linoleic acid nanomicelles[J]. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2016, 145: 56-63.

[41] ZHAO Xiu-rong, SHI Nian-qiu, ZHAO Yang, et al. Deoxycholic acid-grafted PEGylated chitosan micelles for the delivery of mitomycin C[J]. Drug Development and Industrial Pharmacy, 2015, 41(6): 916-926.

[42] GU Chuan-hua, LE V, LANG Mei-dong, et al. Preparation of polysaccharide derivates chitosan-graft-poly(?-caprolactone) amphiphilic copolymer micelles for 5-fluorouracil drug delivery[J]. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces, 2014, 116: 745-750.

[43] MAHAJAN H S, MAHAJAN P R. Development of grafted xyloglucan micelles for pulmonary delivery of curcumin: In vitro and in vivo studies[J]. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2015, 82: 621-627.

[44] XIAO Yu-liang, LI Ping-li, CHENG Yan-na, et al. Enhancing the intestinal absorption of low molecular weight chondroitin sulfate by conjugation with α-linolenic acid and the transport mechanism of the conjugates.[J]. International Journal of Pharmaceutics, 2014, 465(1-2):143-158.

[45] ATKINSON A J, LALONDE R L. Introduction of quantitative methods in pharmacology and clinical pharmacology: a historical overview[J]. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 2007, 82(1): 3-6.

[46] ZHANG Fei-ran, FEI Jia, SUN Min-jie, et al. Heparin modification enhances the delivery and tumor targeting of paclitaxel-loaded N-octyl-N-trimethyl chitosan micelles[J]. International Journal of Pharmaceutics, 2016, 511(1): 390-402.

[47] CHEN Da-quan, SUN Jing-fang. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of PEG-conjugated ketal-based chitosan micelles as pH-sensitive carriers[J]. Polymer Chemistry, 2014, 6(6): 998-1 004.

[48] AGGARWAL B B, SHISHODIA S. Molecular targets of dietary agents for prevention and therapy of cancer[J]. Biochemical Pharmacology, 2006, 71(10): 1 397-1 421.

Researchdevelopmentofhydrophobicfunctionimprovementbyamphiphilicpolysaccharide-basedmicelles

LI Shuang-hong1,YE Fa-yin1,LEI Lin1,ZHAO Guo-hua1,2*

1(College of Food Science, Southwest University, Chongqing 400715, China) 2(Chongqing Engineering Research Centre of Regional Foods, Chongqing 400715,China)

Amphiphilic polysaccharides is a class of semisynthetic polymer with low toxicity, good biocompatibility and degradable. It can form self- assembled hydrophobic- hydrophilic core-shell structure in aqueous. Recently, this kind of micelles got more attention in the field of food science, medicine, biomedical engineering and even material science. The polysaccharide-based micelles research is mainly focused on improving the bioactivity of hydrophobic compounds. Based on the literatures review of the last five years, this paper reviews the applications of amphiphilic polysaccharide-based micelles on targeted delivery, scattered solubilization, delayed release, as well as bioavailability of hydrophobic substances. Finally, the existing problems and future development in this field are also discussed.

amphiphilicity; polysaccharide; self-aggregation; micelles; hydrophobic bioactive compounds

10.13995/j.cnki.11-1802/ts.013448

碩士研究生(趙國華教授為通訊作者,E-mail:zhaoguohua1971@163.com)。

國家自然科學基金面上項目(31371737);重慶市特色食品工程技術研究中心能力提升項目(cstc2014pt-gc8001)

2016-11-21,改回日期:2017-01-18