“熱帶雜交體”

——為亞洲熱帶地區無法控制的城市化進程設計的適應性赤道地區建筑

查蓬·楚恩魯迪莫爾/Chatpong Chuenrudeemol

徐知蘭 譯/Translated by XU Zhilan

2019年的曼谷正面臨社會、政治和環境的危機。城市、郊區和農村地區的發展正在快速增長,主要由私人企業、房地產投機和國際旅游業推動。所有層級的政府機構都尚未跟上步調,并且在很多情況下,在這場肆無忌憚的開發進程中與上述商業機構沆瀣一氣。這種呈指數級的增長也同時深刻地改變了我們所謂的熱帶城市的外部環境和內在基因。在外部環境方面,全球市場的力量和隨之而來的全球建筑語匯使亞洲的大城市變得均質化。

曼谷是吉隆坡是雅加達是萬象是仰光是胡志明市。

審視內部因素,我們充分意識到了城市化進程帶來的社會、經濟和環境問題——污染、擁擠、犯罪、貧困、基礎設施匱乏、幾無所剩的經濟住宅、以及自然災害期間的災難擴大效應等,卻仍比不上我們在21世紀前25年內所見證的程度。盡管這些現象遍及全球,但考慮到東南亞熱帶地區特殊的環境、氣候條件和文化背景,我們所受的影響獨一無二。

在過去幾十年間,新一代的東南亞地區建筑師已經從現代熱帶地區建筑的歷史人物中獲得了寶貴的經驗,如杰弗里·巴瓦和科瑞·希爾。他們的作品是無價之寶,為我們奠定了當代熱帶地區建筑的基礎知識框架。然而,盡管這些大師的杰作具有啟蒙意義,他們仍受限于自身程式化和語境主義的要求。大部分著名的熱帶建筑代表作都是坐落在自然環境中、空間寬敞的高端住宅和奢華度假村,不受城市復雜環境的任何影響。當地設計師對這些大師作品的盲目欣賞經常導致熱帶地區建筑設計的策略錯誤,尤其是那些位于極端城市環境中的建筑。我們對過于外部化的熱帶地區建筑已經司空見慣,它們有宏偉的沿街空間、面向室外開敞的門廳沙發,卻令人懷疑地引入所有的外部城市空間要素——塵埃、煙霧,以及震耳欲聾的交通噪音。另一個同樣危險的極端可能來自于一種人為設定的“熱帶風格”建筑外觀樣式——木檁條、綠植墻、鋁制散熱片——實際上卻是密不透風的封閉式空調箱。

因此我們能很確信地說,許多東南亞的建筑師仍在迷信著“熱帶的神話”,采用著過時的熱帶建筑設計策略。其結果就是,我們仍在為失落的熱帶天堂設計虛假的建筑。

事實上,位于極端城市環境——即四處蔓延的郊區(城市化的郊區環境)和被侵蝕的鄉村地區中的綜合功能建筑設計任務正在大量增加。陳舊的熱帶建筑設計錦囊無法幫助我們接受這些挑戰。作為回應,我們必須把熱帶建筑設計的理念和策略從過去自然浪漫主義的原型推向適應性更良好、空間流暢的熱帶地區建筑雜交體,讓它能有效地關聯新的熱帶地區城市空間。

1 新的熱帶地區城市

如果亞洲的熱帶地區意味著高度全球化和高密度的城市尺度,我們作為建筑師就必須重新考慮熱帶建筑的場所、意義和設計策略。

對我來說,像曼谷之類熱帶地區城市的當代設計狀況表現出難以置信的復雜挑戰。相比曼谷在僅僅10年或15年前的情況,這座城市現在的開發強度更高、污染更嚴重、交通更擁堵且正陷于日益復雜的全球經濟和政治體系中。東南亞熱帶地區的其他大部分主要城市也大多同樣如此。因此,傳統的熱帶建筑設計策略不再完全適用于新的赤道地區大城市環境。

過去,熱帶環境建設致力于遮蔽強烈的陽光和阻隔季節性降水,但也盡可能加強室內的通風。從樹木瑟瑟的搖曳聲到啾啾鳥鳴,大自然的聲響總是很受歡迎。在今天亞洲熱帶地區的大城市中,“大自然母親”的聲音早已被城市摩托計程車和推土機刺耳的喧囂聲吞沒。空氣中開始充斥著由那些噪音制造者的活動所產生的致命微小顆粒。室外空氣不再受人歡迎,其中的CO含量與日俱增。每當城市中微風拂過,僅需要幾小時,所有室內表面都會堆積起層層灰土。被封閉在你那密不透風的大樓里不僅是為了維持室溫,也是為了把自然界的空氣阻隔在外面!

在像孟買、雅加達和曼谷這樣的熱帶地區大城市,空氣質量都只能徘徊在幾乎致命的水平。“曼谷空氣質量指數”顯示可吸入肺顆粒濃度——也就是某些直徑小于10μm的致癌污染物質微粒的濃度——日均數值高達190(推薦的全球安全均值是25)。于是現在的曼谷人只能在街上戴起口罩,讓這座過去曾屬于“熱帶地區”的城市顯現出一幅末日后的景象(不幸的是,對許多中國和印度大城市的居民來說,這番景象已在過去10年間成為新的日常習慣。)。城市空氣質量的問題是我們對亞洲城市熱帶建筑設計原則的探討中的核心問題。

Bangkok of 2019 is in a state of social, political,and environmental crises. Urban, suburban, and rural development is accelerating at increasing speed,spurned on mainly by private industry, real estate speculation, and global tourism. Governmental institutions, at all levels, are not equipped to keep pace, and many times, are complicit in this rampant,uncontrolled development. This exponential growth has had a profound effect on changing both the external pro fi le and internal DNA of what we call the tropical city. On the outside, global market forces and the accompanying Global Architectural language have homogenised the Asian metropolis…

Bangkok is Kuala Lumpur is Jakarta is Vientien is Yongoon is Ho Chi Min City.

Internally, we are well aware of the social,economic, and environmental sickness that come with urbanisation - pollution, congestion, crime,poverty, inadequate infrastructure, depleted affordable housing, and amplified catastrophic effects during natural disasters… but never at the levels we have witnessed in the first quarter of the 21st century. Although these phenomena are occurring in every part of the world, their effects on the Southeast Asian Tropics are unique, due to our specific environment, climate, and culture.

Over recent decades, the new crop of Southeast Asian architects has learned valuable lessons from historical figures of modern tropical architecture,like Geoffrey Bawa and Kerry Hill. Their bodies of work were invaluable in helping us form the foundational knowledge of contemporary tropical architecture. However, as enlightening as these master works are, they are still limited in their programmatic and contextual demands. Most celebrated tropical canons are comprised mostly of high-end residences and luxurious resorts, situated largely in natural settings unencumbered by urban complexities. The unchecked adoration of local designers for these masterworks has frequently resulted in the misappropriation of tropical strategies, particularly in contexts of extreme urbanism. How often have we seen the overly externalised tropical building, with wonderful street-side, open-air lobby lounge that dubiously invite in all the external urban elements - dust,fumes, and the rumble of the street traffic. The other extreme, ever just as dangerous, may come in the form of a building that assumes a "tropical"appearance - wood slats, green wall, aluminum fins - but are essentially hermetically sealed airconditioned boxes.

We can therefor safely say that many architects in Southeast Asia still hold onto the myth of the tropics and employ outmoded strategies of tropical architecture. As a result, we are still designing a false architecture for a lost tropical paradise.

In reality, commissions for buildings with hybrid programs, located in sites of extreme urbanity… sprawling sub-urbanity (an urbanised suburban condition)… and encroached rurality are on the rise. Our old tropical bag-of-tricks do not equip us to meet these challenges. In response we must push tropical design ideologies and strategies past natural romantic archetypes to more adaptive and fl uid tropical hybrids that effectively engage the new tropical urbanism.

1 A New urbanised tropicality

As the Asian Tropics assume a hyper globalised and intensely urban dimension, we as architects must rethink the context, meaning, and strategies of tropical architecture.

For me, the reality of designing in the contemporary Asian tropical metropolis like Bangkok presents an incredibly complex challenge.The city is more developed, more polluted, more congested, and entangled in increasingly complex economic and political glocal systems, compared to the Bangkok of only ten or fifteen years past.This much can be said of most major tropical metropolises in Southeast Asian region. As such,traditional tropical design strategies are not so readily applicable to the new equatorial metropolis.

In the past, tropical environments aimed to filter the harsh sun and monsoon rains, but endeavored to move as much air through its interiors as possible. Sounds of nature from the rustling of trees to chirping of birds were welcome guests. In today's Asian tropical metropolis, the sounds of Mother Nature have long been engulfed by the urban cacophony of motorcycle taxis and bulldozers. The air has become saturated with deadly micro particles from the activity of those very noisemakers. Outside air is no longer a welcome guest with heavier doses of CO. City breezes sweeps in urban dust that accumulate in layers on all interior surfaces in a matter of hours. Being hermetically sealed in your building is not just about keeping conditioned air in,but tainted natural air OUT!

Air quality in tropical metropolis like Mumbai,Jakarta, and Bangkok is on the verge of being deadly. Air Quality Index Bangkok shows PM 2.5 level reading, or particulate pollution of cancercausing micro-particles smaller than 10um, are up to 190 on a daily basis (the recommended global safety average is 25). Bangkokians are now forced to don the PM 2.5 mask while walking the streets, painting a post-apocalyptic picture of this once "tropical"city (Unfortunately, to many living in metropolitan China and India, this had been the new norm for the past decade.). The issue of urban air quality is very a core issue in our discussion of tropical design principles in the Asian city.

If we are to assume that one of the main directives of tropical design principles is "to maximise natural air flow and ventilation to achieve thermal comfort", then we have reached a serious dilemma:

How do we naturally ventilate our buildings when the very air we are inviting in is, in fact, toxic?

The new tropical architecture must now confront the many demands of this new untamed Tropical Asian city, bursting at the seams. Equatorial architecture must flex its muscles by moving beyond the romantic honeymoon phase to become the tropical sentry that effectively negotiates the contaminated nature and untamed urbanism of the new Tropical Metropolis.

如果我們假設熱帶建筑設計的主要指導原則之一是“最大程度促進自然通風和換氣,以實現熱舒適功能”,那么就會面臨嚴重的矛盾:

我們應該如何以自然的方式實現建筑通風?如果我們引入的空氣恰恰實際上……是有毒物質呢?

新的熱帶地區建筑設計現在必須面對新的、失控的亞洲熱帶地區城市這一暴增的需求。赤道地區的建筑必須超越浪漫蜜月的階段,成為赤道地區的哨兵,使其肌肉得到放松,才能在受到污染的自然和新興熱帶地區大城市不受控制的城市化進程之間進行有效地平衡。

2 具有社會包容性的熱帶地區項目

亞洲熱帶地區建筑的功能設計必須更具包容性。在住宅和度假設施建筑之外,熱帶建筑的設計原則必須重新審視如何為亞洲城市中的低收入階層提供住宅、供給和必要的生存條件。

在曼谷,我們正在經歷整個東南亞地區低收入階層在熱帶地區城市空間形態方面的大幅度削弱。當地的菜市場(talad sod)、戶外跳蚤市場 (talad naht)、傳統棚屋社區(chum chon)都逐漸從曼谷的街景中消失。這在很大程度上與人們對這些較低階層的熱帶城市空間類型的誤解報以回避、忽視和毫不顧忌的態度有關,從而把它們當做貧民窟建筑和城市的眼中釘來對待。但它們是為曼谷底層勞動階層提供住宅、供給和維持生計的重要載體,卻正從曼谷的景觀和泰國的文化意識中迅速消失,令人悲嘆。

除了它們的文化和社會價值,我們還需要從經濟學的角度考慮這些正在消失的本土建筑類型對城市經濟等級制度具有的重要意義。我們不禁要問:“如果這些空間形態被高端住宅和購物商場所替代,那么勞動階層將在哪里生活、飲食、消費和住宿?”照此推理,會由誰來擦洗桌面、整理貨架、打掃街道和為占據了這些全球城市開發空間的中上階層人士提供高級公寓的清潔服務?當前對現有熱帶城市建筑類型的搬遷/拆毀已經導致城市較低階層居民的遷徙,反過來也導致災難性的經濟不平衡狀況。考慮到這一現實狀況,我們必須提問,即熱帶地區建筑的經驗將如何延伸,為亞洲大城市中更底層的勞動階層提供新的熱帶地區城市空間類型?

3 傳統泰式住宅:熱帶地區生存的雜交體模型

回顧歷史,泰國的農業景觀及其附近的森林地區在很大程度一直被其所有者同時視為令人歡迎的資源提供者和兇殘的敵人。河流為水稻種植提供人們需要的充沛水源,卻也同時在雨季造成頻繁的洪災,輕易摧毀他們一整年的收成。人們從森林砍伐木料用于建造住宅和雕刻器物,同時森林也是野生哺乳動物和爬行動物的棲息地,它們常常是農莊的野蠻侵襲者。由農民和當地寺廟僧侶共同構成的社區鄰里在任何一天都能快速地共享幸運的收獲,從稻米到蔬菜、織布以及偶爾由水牛來耕作田地的機會。但在社區內部,總有意圖可疑的人。尤其是在遭遇戰爭、干旱、洪水和其他自然或人為災害的時候,乞丐、騙子和小偷紛紛出動。

傳統的泰式高蹺房屋,或稱泰式“巴恩魯恩”,也因此被理解為是一種用來抵御既豐饒、又令人無法釋懷的泰國自然環境的建筑類型。這一類型在我們的鄰國也有類似的體現——老撾的“胡恩勞”、緬甸的湖中浮屋、馬來西亞的“昆蓬”民居,以及印度尼西亞的巴塔克式建筑 。

泰式“巴恩魯恩”房屋在許多方面非常適合熱帶的自然環境。

由木構件建造的輕質預制結構、木板和壓條的嵌板、藤制、竹制或木制的板條填充構件,以及茅草屋頂等構造,讓建筑物能在泰國的熱帶氣候中進行呼吸順暢。高聳的坡屋頂能讓雨季降水迅速蒸發,在山墻面上大面積開洞并覆蓋百葉窗能在潮濕的環境中加速屋頂通風。在“代敦”處——也就是傳統架空房屋中部下方有樹蔭遮蔽的空間,室內外空間有非常明顯的相互重疊。白天,未在水稻田間勞作的家庭成員就在此處躲避強烈的日照或熱帶的降雨。這處奇妙的空間條件由3個最簡潔的元素構成——下方骯臟的泥地、上方的木質地板、以及自由分布的木柱。老年人和孩子們在這一多功能的開敞式平面空間里度過一天中的大部分時間,他們在這里玩耍、閑聊、休息、做飯、完成雜務、也在織布機上制作日常穿戴的衣物。

然而,盡管傳統泰式住宅的類型設計能讓建筑結構在和平、繁榮且溫和的氣候條件下與熱帶環境充分融合,其類型的基因則同樣能夠用來抵御野外農業景觀環境帶來的危險。把建筑架高在木樁上是一種幫助居住者躲避熱帶地區自然天敵——季節性洪水的方式。在雨季,長期浸沒在靜止水體中的環境會帶來霉菌、有毒的爬行動物、攜帶瘧疾致病源的蚊蟲,以及通過水源傳播的疾病。在這些頗有挑戰的情況下,高蹺房屋讓居住者能夠長久地保持在安全地帶生活。極端的洪災和過于漫長的干旱也可能讓農民決定遷徙到其他地區。作為一種響應性措施,建筑的柱體、梁、椽、地板等都能夠拆除并裝在水牛車上運往別處,甚至標志性的“法巴恭”——也就是泰式住宅交錯拼接的木板和壓條嵌板——也是一種把易于運輸的小規模構件以藝術的方式進行拼接的獨特構件體系。構件組裝式的傳統泰式房屋讓人能在面臨熱帶地區自然災害之時通過拆除和重新組裝實現自由遷徙。

居住在自然環境中的家庭每天都面臨著各種威脅,日落之后尤其危險。在夜間,野生動物離開了附近森林的保護,到農莊捕食無助的牲畜。有毒的爬行動物則在更涼爽的夜間出來覓食。行蹤可疑的人也覺得在鄉村的夜晚四處游蕩更為自由。為了保護家人免遭夜間環境的危險,泰式“巴恩魯恩”把自己變成了一座熱帶森林。所有家庭成員在夜間休憩的主要室內空間都在高處,遠離地面四處遍布的危險。這些架高的人字形屋頂空間設有窄小的門窗,從內部很容易上鎖,并在室內覆以厚重而無法看透的實木百葉窗。但頂部連續嵌板通風百葉窗仍可在炎熱潮濕的夜晚進行空氣流通。

因此,我們認為傳統的泰式房屋既是對熱帶生活積極因素的回應,也能夠抵御泰國熱帶雨林景觀到處充滿野外危險的狀況,它并不是當代熱帶建筑所表現出的永遠只有室外化設計的、單調的浪漫場景。建筑在白天限定出一處“開敞式的平面”作為室外的起居室——即“代敦”,以共享的理念向周圍美妙的農業社區自由開放。到了夜晚和面臨社會與環境災難時,它則化身為一座防御工事;出于對竊賊、入侵者和四處游蕩的野生動物的恐懼,它切斷了和外部世界的所有聯系。

4 新型熱帶地區城市空間原型

通過對這些“曼谷雜交體”進行研究、和與其中的居住者進行訪談所得的綜合經驗,我們形成了熱帶地區雜交體的建筑學,試圖適應新興熱帶地區城市化的挑戰。室外空氣對建筑通風和園林景觀來說必不可少,卻同時又具有致命的粉塵污染;新的類型對如何解決這一熱帶地區城市空氣的矛盾問題提出了可能的解決方案。新的熱帶城市空間類型利用受保護的空間作為曼谷的“濾肺”,從而在曼谷形成一種新的空間條件類型,面對多樣的熱帶地區環境。

4.1 圍墻住宅雜交體

出于對乞丐、粉塵和噪音的恐懼,泰國的許多城市都出現了類似曼谷郊區住宅區用空白的實墻把每座住宅都包圍起來的做法。它們讓許多住宅區街道的人行道變得面無表情,也阻隔了原本可以在街巷和私人庭院內形成的空氣流通。曼谷目前的圍墻住宅類型正在迅速毀滅熱帶地區城市生活的潛質。

2 A socially inclusive tropical programme

The focus of programmatic content of tropical Asian design must be more inclusive. Outside of residential and resort architecture, tropical design principles must be re-thought to house, feed, and sustain the Asian city's lower class.

In Bangkok, we are now witnessing the decimation of entire urban tropical morphologies of the Southeast Asian lower class. The local "talad sod" (fresh markets), "talad naht" (open-air flea market), and "chum chon" (traditional urban shanty neighbourhoods) are slowly disappearing from Bangkok streetscapes. That is due in large part to the misunderstanding that these urban tropical typologies for the lower class, are frequently shunned, overlooked, and swept aside as slum architecture and urban eyesores. Yet, they are critical vessels for housing, feeding, and sustaining the lower working class of Bangkok, but sadly are quickly disappearing from the Bangkok landscape and Thai consciousness.

Aside from their cultural and social value,we should consider the economic importance of these disappearing local building types in the urban economic hierarchies. We are forced to ask,"When these morphologies are replaced by highend condominiums and megamalls, where will the working class live, eat, shop, and sleep?" Logistically then, who will then buss the tables, fi ll the shelves,sweep the streets, and clean the apartments of the upper-middle class that occupy these global urban developments. The current removal/destruction of existing tropical urban typologies have led to the displacement of the lower class inhabitants in the city, which in turn, will result in a devastating economic imbalance. With this reality, we must then ask how the lessons of tropical architecture can be learned to create new urban tropical typologies for the lower, working class in the Asian metropolis.

3 The traditional Thai House: a hybrid model for tropical survival

Historically, Thailand's agricultural landscape and its adjacent forests have largely been perceived as both benevolent provider and malevolent foe to those who occupied them. The rivers that provide the abundance of water needed for the cultivation of rice also send frequent fl ash floods during monsoon season that can easily decimate the year's bounty.The forest from which timber is cut and utilised to build houses and carve wares, are habitats for wild animals and reptiles that are frequent savage invaders of the farmstead. Community neighbours consisting of farming and local temple monks are quick to share any good fortune on any given day,from rice, to vegetables, textiles, and occasional buffalo labour to plow the fields. But within that community are always characters of dubious intent. Burglars, swindlers, and thieves come out of the woodwork, especially in times of war,drought, flooding, and other naturalor manmade catastrophes.

The traditional Thai house on stilts, or baan ruen Thai, was therefore envisioned as an architectural typology of defence against the bountiful, yet unforgiving Thai landscape.(This typology has similar manifestations in our neighbouring countries - the huen Lao in Laos, the floating house in Myanmar, the kumpung house in Malaysia, the Batak house in Indonesia).

In many aspects, the baan ruen Thai welcomes in the tropical environment.

Its light componential construction of timber,board and batten paneling, rattan/bamboo/wood slat infill, and thatched roof allow the structure to breath in Thailand's tropical climate. It high pitched roof, allowing quick drainage of water during monsoon rains, contain large slatted openings at the gabled ends to allow for roof ventilation in the humid conditions. The overlap between indoor and outdoor is most apparent in the tai tun, or the underbelly of the elevated house. During the day,family members who are not working the paddy fields could be found in the underbelly of the house,shaded from the harsh sun or tropical rains. The spatial limits of this wonderful space is comprised of 3 minimal elements: the dirt ground below,the wooden floor plate above, and free flowing wooden columns. The elderly and children spend the majority of their days in this multipurpose openplan space, playing, chatting, lounging, preparing food, doing chores, and weaving garments for daily use on the loom.

However, as the traditional Thai house's typological design allows the structure to embrace the tropical environment in times of peace,prosperity, and temperate climate, its typological DNA was also developed to defend against the hazards that accompany the untamed agricultural landscape. Lifting of the house up on stilts was one way to help inhabitants escape one of the tropical landscape's natural enemies… the seasonal floodwaters. During monsoon season, a landscape continually submerged in stagnant water can bring with it mold, poisonous reptiles, malaria-carrying mosquitoes, and water-borne disease. During these challenging times, the elevated house lifted the occupants to safety for sustained periods. Extreme flooding and prolonged droughts may also forces the farmers to migrate to different locations. As a response, columns, beams, rafters, floorboards of the house can be disassembled and loaded onto buffalo cart for transport. Even the iconic fah pakon,or iconic staggered board and batten paneling of theThai house, is an ingenious system of stitching small pieces of easy-to-transport panels in an artful way.The componential construction of the traditionalThai house makes this possible as disassembly and re-assembly of the residence allowed freedom of movement in times of tropical natural disasters.

The landscape posed a threat to the family on a daily basis and was most dangerous after sunset.At night, wild animals left the protection of the nearby forests to feed on the helpless livestock of each farmsteads. Poisonous reptiles emerge in the cooler nighttime temperatures for feeding. Shady characters with questionable intentions felt freer to roam the countryside at night. To protect the family against the nighttime threats, the baan ruen Thai transformed itself into a tropical wooden fortress.The main interior spaces to which all members retired at night are elevated, removed from hazards roaming on the ground level. These raised gabled pavilions contained small, narrow window and door openings, easily locked and braced from the inside by thick impenetrable solid wood panel shutters.However, continuous bands of slatted ventilation panels above still allowed air to flow inside on hot steamy nights.

2 愛卡麥住宅保護性且充滿活力的圍墻/Ekamai Residence,protective and pourous perimeter wall(攝影/Photo:Spaceshift Studio)

3 愛卡麥住宅受保護且通風良好的庭院/Ekamai Residence,protected and ventilated court(攝影/Photo: Masano Kawana)

4 薩拉阿麗雅瑜伽學校與住宅保護性且充滿活力的圍墻/SalaAreeya, protective and pourous perimeter wall (攝影/Photo: Prueksakun Kornudom)

5 薩拉阿麗雅瑜伽學校與住宅受保護且通風良好的夾道SalaAreeya, protected and ventilated alley (攝影/Photo: Karn Chuensriswang)

Thus we see that the traditional Thai house as a response to both the positive elements of tropical living as well as the untamed hazards of a tropical landscape in Thailand was hardly the singular romantic picture of eternally exteriorised of a contemporary tropical building. A structure that in the day, defined an "open-plan" outdoor living room, the tai tun, that opened itself freely to the wonderful agricultural community based on sharing.At night and during social and environmental trauma, it became a defensive fortress, closing all ties to the outside world in fear of thieves, invaders,and roaming wild animals.

4 New tropical urban prototypes

Incorporating lessons learned from the research of these Bangkok Bastards and from interviews with their inhabitants, we have developed hybrid tropical architectures that attempt to adapt to the challenges of the new tropical urbanism. The new types suggest potential solutions for the dilemma of negotiating the urban tropical air that is both necessary for ventilating buildings and gardens, but at the same time, hazardous in their dust and pollution levels.The new tropical urban typologies utilise protected voids that become the " filtering lungs" for Bangkok,allowing for a new types of spatial conditions of hybrid tropicality in Bangkok…

4.1 The perimetre wall residential bastards

Fear of burglars, dust and noise in Thailand's cities have brought about blank, solid, impenetrable street walls that cocoon every house in Bangkok's sub-urban neighbourhoods. They render most residential streets without a pedestrian face and block air flow that could circulate in the alleys as well as the private yards. Bangkok's current perimetre wall house typologies are quietly killing the potential for urban tropical living.

The Ekamai Residence aims to bring life back to the residential streets of Bangkok by considering the house and the perimetre wall as one entity. By reconsidering the perimetre wall as a vital residential component rather than an infrastructural afterthought, the house allows us to envision new tropical typology in Bangkok's complex urbanism. The operable louvered perimetre wall re-establishes the lost connections between the private and public realms (that once existed in the city's shop house neighbourhoods), without sacrificing safety and security. The panels can be opened for owners to connect to the city... whether chatting with neighbours, buying snacks from street vendors, or engaging in water fights with neighbourhood kids during Thai Songran Season.When open, the openings allow full breezes to enter the garden and interiors. Once closed for occasions that warrant privacy, filtered air can still pass through the wooden slats, allowing the yard to breath. Boundaries between house, garden, and street become blurred, and city life flows freely. At night, the panels can be closed and securely locked,to protect the inhabitants from the perils of the city.

SalaAreeya is a private residence that doubles as a yoga school for the neighbourhood. The house is conceived not so much as a building,but as a soi ("alley" in Thai). And like in many Bangkok alleyways, where the path is both public thoroughfare and community living room, the programmed soi in SalaAreeya also has a double function. When the operable street wallof the house is closed, the garden alley acts as a private open-air living room for the owner. When the street walls are thrown open, the private house turns into a public school, and the alley transforms becomes an extension of the street, inviting neighbours in to practice yoga, chat, eat, drink, and play.

4.2 The tunneled courtyard hybrids

The Nanda Heritage Hotel sits on a unique urban threshold of old and new… between a highspeed motorway on one side, and a peaceful 100-year old historic community on the other. It is conceptualised as a building within a building.The dark billboard-like concrete outer mass (guest rooms) serves as a protective outer shell that encases a wood and steel inner courtyard. Like the curtain sex motel Bangkok Bastard, an entry tunnel from the street becomes a sieve that regulates polluted air and city noise for the void at the central court (the "lung" of the building).

The tunneled court typology is a negotiator of the urban tropical city. It allows for the building to have open space that is naturally ventilated, but properly regulated for the safety and comfort of the occupants in terms of air and noise pollutants.As such the building can then entertain outdoor activities despite the hazards of the environment.

The Samsen Street Hotel is the renovation of a curtain sex motel, one of the city's existing Bangkok Bastards. True to its typology, it has an inner courtyard accessed by a tunnel through the street elevation. The tunnel regulates both visitors and natural air into the protected courtyard. The central void, once a auto-arrival court has been transformed into a "nahng glahng plang" (outdoor movie theatre commonly found in Thai rural festivals) with community lounge pool.

The scaffolding elements of the Street Hotel are derived from scaffolding elements found in another Bangkok Bastard - the construction worker house. The sidewalk scaffolding accommodates open air street terrace that have mobile furniture that can colonise the street (much like how public paths in local waterside shanties are appropriated as extensions of the houses along them). The "soi" is a maze-like vertical alley used to serve MEP utilities doubled as a vertical stage for street concerts.

5 Tropicality for a new dense rurality

However, innovation and hybridisation in tropical architecture need to be applied to areas still neglected, particularly in the rural countryside. As Thailand's population increases each year, there is an epidemic of urbanising farmland in the name of progress and development. The stigma commonly persists that rice farming, historically one of the main industry that has sustained Southeast Asia,is an outdated as a way of life and unproductive as a national industry. Adding to this dilemma is the government's biased allotment of funds, favourable policies, and trade benefits toward industry and tourism. Compounded with global warming and local deforestation (both contributing sustained droughts and uncontrolled flashfloods) the rice paddy, Thailand's historically dominant cultural landscape typology, is slowly disappearing.

With so many challenges working against farming as a viable and sustainable way of life, young people in rural areas are flocking to cities in search for higher paying factory/office jobs and positions in the service industry, both legal and underground. This leaves the countryside depleted with a growing elderly population that cannot physically and economically sustain the rural landscape on their own.

Architecture cannot solve every problem in the social, political, and economic realm, but it does have to power to suggest new architectural and infrastructural alternatives for a more productive, sustainable, and happy way of life. We can propose new tropical,affordable, culturally-infused models of high-density low-income housing, markets, and retail that will sustain a larger rural population… without sacrificing the tropical, natural, agricultural way of life. Instead of the go-to solution of farmland "development" through urbanisation, can we find a new tropical solution in creating a high-density rurality?

6 織布機膠囊/Loom Condon

愛卡麥住宅的設計目的就是通過把住宅和圍墻作為整體進行考慮,來重現曼谷的住宅區街道。通過把圍墻當作重要的住宅構成要素來考慮,而不是住宅建成后的配套基礎設施,這些建筑讓我們可以預見,在曼谷復雜的城市化條件下可以產生新的熱帶建筑類型。可開合的百葉窗圍墻重新建立了私人和公共領域之間的關聯(這種聯系過去一度出現在城市的社區商店),而無需犧牲安全保障。面板可以由業主打開,和城市空間聯系在一起——無論是和鄰居閑聊、從過街商販處購買小吃、還是在泰國宋干節(潑水節)期間和鄰居的孩子們一起加入潑水大戰。門洞打開時,可以把微風引入花園和室內。需要確保私密性時,門洞可以關閉,經過濾的空氣仍能通過木板進入庭院。住宅、花園和街道之間的界限變得模糊,城市生活得以自由流動。在夜晚,面板可以鎖閉,保護居住者免遭城市的危險。

薩拉阿莉雅是一座私人住宅,同時也是社區瑜伽學校的所在地。這座住宅不是作為建筑而是作為“綏”(泰語“街巷”)來設計的。就像曼谷的許多街巷一樣,巷道既是公共通道,也是社區的起居空間,薩拉阿莉雅經過設計的街巷也有雙重的功能。在可調節的住宅沿街圍墻關閉時,花園通道僅作為業主私人的室外起居空間使用,而在圍墻打開后,私人住宅又會變為向公眾開放的學校,這條小巷則成為街道的延伸,邀請周圍的鄰居來此做瑜伽、聊天、飲食和玩耍。

4.2 通過隧道銜接的庭院雜交體

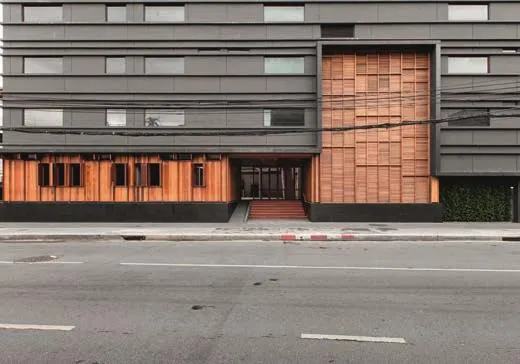

南達遺產酒店的位置十分特殊,處于城市的新舊區交界處——一側是高速公路,另一側則是寧靜的歷史街區,已建成百年之久。其設計理念是在建筑中再設計一座建筑。大片的深色混凝土外立面 (客房)看似廣告牌,實則是一層保護性的外殼,內部是一個庭院,由木材和鋼建成。和“曼谷雜種”(見102頁)的某座汽車旅館改造項目類似,從街道延伸進來的整條通道共同形成一個建筑的濾網,把外部被污染的空氣和城市噪音引導到中央庭院(也就是建筑的“肺部”)進行處理。

通過隧道銜接的庭院類型是熱帶城市的溝通者,它能讓建筑在擁有自然通風的開敞空間的同時,對空氣污染和噪音污染進行處理,為居住者提供安全和舒適的條件。建筑物能由此提供室外活動場所,而無需考慮環境的危險。

薩姆森街酒店是某座汽車旅館的翻新項目,也是城市中現有的“曼谷雜種”之一。這座建筑遵循其類型,有一個內部庭院,能從街道立面上通過隧道進入。這條隧道同時把訪客和自然的空氣引入內部受保護的庭院。其中庭曾是一處泊車空間,如今被改為帶有可休憩游泳池的室外電影院(在泰國鄉村地區的節日期間很常見)。

街道酒店的腳手架元素取材于另一處“曼谷雜種”——建筑工人住宅處找到的要素。人行道上的腳手架形成了開敞的街道平臺,其中布置可移動家具,可以占據街道空間(很像當地水邊棚屋的公共通道作為沿街住宅空間延伸的做法)。項目把“綏”設計為一種迷宮般的垂直街巷,用來容納工程設備,同時也是街道音樂會的垂直舞臺。

5 新的熱帶地區高密度鄉村

熱帶地區建筑的創新和混雜還需要運用在目前仍被忽視的地區,尤其是偏遠的鄉村地區。由于泰國人口每年持續增長,目前流行以進步和開發的名義對鄉村土地進行城市化的做法。對農村進行污名化的理由通常是,認為水稻的種植——過去曾是東南亞地區最主要的產業之一——作為一種生活方式已經過時,而作為全國性產業則生產力低下。加劇矛盾的因素還體現在政府資金分配的傾向、優惠政策和貿易利潤,都更有利于工業和旅游業,加之全球變暖和當地森林砍伐(兩者都造成了持續的干旱和失控的山洪爆發),曾在泰國歷史上占主導地位的水稻田文化景觀正在緩慢消逝。

由于農業耕種作為維持生計的可持續的生活方式面臨如此之多的挑戰,農村地區的年輕人正向大城市蜂擁而至,尋求收入更高的工廠、辦公室的工作和服務業的崗位,無論它們是合法的還是非法的留下一個資源消耗殆盡、人口老齡化日趨嚴重的農村,無法依靠自身力量在物質空間和經濟方面維持田園景觀。

雖然建筑無法解決社會、政治和經濟領域的所有問題,卻仍有力量為一種更具生產力、更可持續發展和能令人幸福的生活方式提供新的建筑和基礎設施設計的建議。我們能提出一種新型高密度的低收入住宅及其市場和銷售方式,這種住宅能適應熱帶環境、經濟適用,并在文化上具有融合性,能為更廣泛的鄉村人口提供生存條件,同時也無需犧牲熱帶地區的自然、農業的生活方式。除了通過城市化對農田進行“開發”的轉換方式,我們可否找到一種新的熱帶地區解決方案,形成高密度的鄉村空間?

織布機膠囊是為新的高密度熱帶地區建筑設計的概念原型,以幫助我們重新審視一種生產力更為發達的泰國農業景觀。考慮到沙功那空府的老年紡織品編織者需求,這個新的“農村雜交體”包含多個家庭和跨代際的聚落形式,將有助于激勵城市移民回歸生產力發達和可持續發展的農村生活。這座建筑是由從廢棄的傳統泰式房屋回收的木料建成的混合雜交體,也是一系列泰式“非建筑學”的農業原型,具體包括:

(1)“達額”,即傳統泰式房屋“代敦”中能見到的低矮而寬大的桌子,或是傳統泰式高蹺房屋中部有遮蔽的空間。當地人,尤其是老年人,在這個傳統的全功能平臺上坐臥休憩、用餐和做飯。

(2)“蒙”,即一種防蚊帳,像帳篷一樣的懸掛結構。

(3)“格希”,即紡織機,是水稻景觀的重要設備,男性成員在水稻田勞作的同時,老年婦女和10~20歲之間的女孩用它為全家紡織衣物。

這種建筑與“非建筑”要素之間的融合來源于“曼谷雜種”的設計策略,旨在通過使用便于獲得的、可持續的日常設備形成非正式的熱帶地區空間。

我們有可能創造出多種新型熱帶地區建筑模式,來實現這項新的高密度農村的景象。當地的青年人現在被薪資普通的工廠或辦公室崗位吸引,向大城市移民,這一景象會吸引他們回歸具有生產力的農業生活。它將鼓勵農村的老年人重拾逐漸被人遺忘的農業傳統和本土的手工藝,它們具有高度的價值。而把年輕一代留在農村和年長一代共同生活,能實現文化知識的傳承,從而讓鄉村生活變得具有可持續性和生產力,成為城市生活之外的另一種選擇。□

The loom condo is a conceptual prototype for a new high-density tropical architecture to help us re-envision a more productive Thai agricultural landscape. Designed with the elderly textile weavers of Sakon Nakorn Province in mind, this new Rural Bastard accommodates multi-family and intergenerational dwellings that will help stimulate a return to productive and sustainable rural life for city migrants. Its structure is hybrid mix of reclaimed timber from abandoned traditional Thai homes... and Thai agricultural "non-architecture"archetypes including:

(1) The tahng, or large, low-lying hybrid table,is found in the tai tun, or shaded underbelly of the traditional Thai stilt house. Locals, especially the elderly, sit, nap, relax, eat, and prepare meals on this traditional all-purpose platform.

(2) The moong, or mosquito net, that becomes a hanging tent-like structure.

(3) The ghee, or textile loom, a key ricelandscape apparatus that allow women, elderly, and teens to weave clothes for family while men are working the rice paddies.

This fusing of architectural and "nonarchitectural" components is derived from Bangkok Bastard strategies that aim to create informal tropical spaces using easy-to-find, sustainable,everyday devices.

It is possible to create new models of tropical architecture to fulfill this vision of a new dense rurality, one that will attract young locals, now seduced to migrate to cities for regular wage factory or office jobs, to productive agricultural living. It will encourage the elderly in the countryside to rehabilitate the valuable traditions in agriculture and indigenous craft that are slowly being forgotten.Keeping the younger generation with the older generation in the countryside will allow a transfer of cultural knowledge that will make rurality a sustainable, productive alternative to city life.□

7 南達遺產酒店隧道入口/Nanda Heritage Hotel, tunnel entry

8 南達遺產酒店受保護的庭院/Nanda Heritage Hotel, protected court(7.8攝影/Photos: Ketsiree Wongwan)

9 薩姆森街酒店街邊小攤立面及入口隧道/Samsen Street Hotel, street food fa?ade with entry tunnel

10 薩姆森街酒店受保護的戶外電影庭院/Samsen Street Hotel,protected outdoor movie court(6.9.10繪圖/Drawings: CHAT Lab)