雙相障礙患者的風險決策偏好:來自三水平元分析的證據

摘 "要""本研究采用三水平元分析定量估計雙相患者與健康個體的風險決策偏好差異, 并檢驗該差異是否受到樣本特征和測量特征的調節。基于71篇文獻和176個效應量的元分析發現, 雙相患者比健康個體更偏好風險尋求(Hedges' g"= 0.301), 且這一偏好在風險態度量表(Hedges' g"= 0.624)、行為實驗任務(Hedges' g"= 0.252)和日常風險行為(Hedges' g"= 0.312)中都穩定存在。同時, 該差異還受到年齡(β"= 0.009)和心境階段的調節, 其中不論心境階段如何, 雙相患者均比健康個體更偏好風險尋求(緩解期: Hedges' g"= 0.245; lt;輕gt;躁狂期: Hedges' g"= 0.604; 重性抑郁期: Hedges' g"= 0.417)。此外, 在行為實驗任務中, 該差異受到年齡(β"= 0.012)和地區的調節。特別是歐洲(Hedges' g"= 0.419)和南美洲(Hedges' g"= 0.420)的患者, 以及在愛荷華賭博任務(Hedges' g = 0.396)和劍橋賭博任務(Hedges' g = 0.220)中的患者, 均比健康個體更偏好風險尋求; 而在日常態度和行為中, 該差異僅受到心境階段的調節, lt;輕gt;躁狂期患者(Hedges' g"= 0.747)比健康個體更偏好風險尋求。本研究首次通過多種風險決策偏好測量類型探討雙相障礙與風險決策的關系, 得出了較穩定的結果, 并提出未來研究應充分考慮心境階段、任務類型等因素的影響, 深入挖掘雙相障礙影響風險決策的心理機制, 為雙相障礙的臨床管理和心理教育提供參考。

關鍵詞""雙相障礙, 風險決策, 元分析, 決策范式, 跨心境特異性

分類號""B849: C91; R395

1 "引言

雙相障礙(Bipolar Disorder)是一種以躁狂、輕躁狂、重性抑郁交替反復發作為特征的心境障礙, 影響著全世界約4000萬人(WHO, 2022), 也是我國六大重性精神障礙之一。雙相障礙的全球終生患病率約為2.4%, 部分地區高達4.4% (Merikangas et al.,"2011), 而在我國約為0.6% (Huang et al., 2019)。雙相患者認知、社會和職業功能受損, 有極高的自殺傾向, 容易做出有災難性后果的行為。據調查, 雙相患者自殺率是精神障礙中最高的, 約為一般人群的20~30倍(Plans et al., 2019), 其中15%~20%的自殺企圖是致命的(Schaffer et al., 2015)。受其影響最大的是社會主要勞動人口(Plana-Ripoll et al., 2023), 因此該疾病會造成嚴重的經濟和社會成本。然而, 雙相障礙心境交替乃至混合發作的復雜特征, 使其易誤診、難治療。鑒于雙相障礙的普遍性、嚴重性和復雜性, 學界一直重視探索其認知和行為特征, 以助于有效識別、評估和干預。

決策(Decision-making)作為高級認知功能, 又關乎個體日常行為, 其如何受雙相障礙的影響備受關注。有研究發現雙相患者的決策功能受損, 容易做出非理性、不適宜的決策(如Amlung et al., 2019; Ramírez-Martín et al., 2020), 進而影響其行為。雙相患者的風險決策尤為重要, 它可能產生潛在的嚴重后果, 不僅關乎患者的社會、職業功能, 甚至可能危及其身體健康和生命安全, 如自殺行為等(Miller amp; Black, 2020)。因此, 有必要深入了解患者的風險偏好, 及時識別并干預其風險行為。

風險決策(Risky Decision-making)是指個體在不確定情境中的決策, 其風險決策偏好(簡稱風險偏好)常分為風險尋求和風險規避。風險尋求(risk-seeking)是指個體在面對多個風險選項時選擇高風險選項的傾向(Lejuez et al., 2002; Meertens amp; Lion, 2008)。與之相反的是風險規避(risk-aversion)。雙相障礙的診斷標準指出, 患者在躁狂或輕躁狂發作時容易過度參與那些很可能產生痛苦后果的高風險活動(APA, 2013), 這意味著雙相患者常伴有風險決策異常。對患者的臨床觀察(Krantz et al., 2018; Williams et al., 2017)、行為實證研究(Edge et"al., 2013; Richard-Devantoy et al., 2016)和神經影像學研究(Blankenstein et al., 2017; Miklowitz amp; Johnson, 2006)也表明雙相障礙會影響患者的風險偏好。

以往研究主要通過比較雙相患者與健康個體在風險偏好上的差異來探討雙相障礙對風險決策的影響, 但所得結論并不一致。早期研究者根據躁狂或輕躁狂診斷中“過度地參與那些很可能產生痛苦后果的高風險活動” 的標準, 結合雙相障礙常與風險行為相關的精神障礙共病(如, 物質使用障礙和破壞性、沖動控制與品行障礙) (APA, 2013), 推測雙相患者比健康個體更偏好風險尋求(如Ernst et"al., 2004; Holmes et al., 2009), 且這一推測也得到了行為實證研究和神經影像學研究的證據支持。一方面, 以往研究通過比較雙相患者與健康個體在自陳量表和行為實驗任務中的風險偏好, 發現雙相患者比健康個體更偏好風險尋求。如, 在自陳量表上, 雙相患者在特定領域風險態度量表(Domain-"Specific Risk-Taking Scale, DOSPERT)和反應風格量表(Response Styles Questionnaire, RSQ)的冒險維度上的得分均比健康個體更高, 更偏好風險尋求(Pavlickova et al., 2014; Thomas et al., 2007); 在行為實驗任務中, 雙相患者比健康個體在愛荷華賭博任務(Iowa Gambling Task, IGT)中更偏好選擇不利卡牌, 即風險選項(Edge et al., 2013); 在劍橋賭博任務(Cambridge Gambling Task, CGT)中下的賭注更高, 即更偏好風險尋求(Linke et al., 2013)。另一方面, 神經影像學證據也表明, 雙相患者的大腦結構較健康個體有所變化, 且這一變化與風險決策有關, 使其可能更偏好風險尋求。如, 患者的額葉白質束完整性下降, 研究表明這種完整性破壞使其更偏好風險尋求(Scholz et al., 2016); 又如, 患者的頂?枕?小腦網絡灰質減少, 使其沖動性增加, 更容易做出風險行為(Lapomarda et al., 2021)。因此, 越來越多研究者認為, 風險尋求增加是雙相患者常見的認知和行為特征, 并可能成為雙相障礙潛在的核心癥狀之一(H?d?ro?lu et al., 2013; Ramírez-Martín et"al., 2020)。

然而, 近期有一些研究卻發現雙相患者的風險偏好并非始終不同于健康個體(如Martino et al., 2011; Reddy et al., 2014), 甚至有些研究表明雙相患者比健康個體更偏好風險規避。如, Wong等人(2021)采用氣球模擬風險任務(Balloon Analogue Risk Task, BART)發現, 雙相患者在未爆炸氣球中的平均按壓次數和氣球爆破率都顯著小于健康個體, 即更偏好風險規避。Hart等人(2019)則采用概率折扣任務(Probability Discounting, PD)發現, 雙相患者的折扣率顯著大于健康個體, 即更偏好保守選項。本研究在深入分析上述相互矛盾的研究結果后, 推測雙相患者與健康個體風險偏好差異的方向以及程度可能受到三個方面的影響。

1.1""心境階段的調節作用

雙相患者的風險偏好可能隨心境階段變化而變化。根據美國精神疾病診斷與統計手冊第五版(Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder Fifth Edition, DSM-V; APA, 2013), 雙相患者有時會表現出心境膨脹、極度自信, 目標活動增多, 易過度參與高風險活動, 即lt;輕gt;躁狂期, 包括躁狂發作和輕躁狂發作; 而有時則會表現出情緒低落、自我貶低, 思考能力下降或猶豫不決, 幾乎對所有活動的興趣或愉悅感都明顯減少, 即重性抑郁期(簡稱抑郁期), 對應重性抑郁發作。兩者常統稱為發病期。而發病間隙患者的癥狀得到緩解, 情緒趨于穩定, 即緩解期。因此, 患者存在3種不同的心境階段, 且在不同心境階段下他們的認知、動機和行為表現都有明顯差異。

健康個體的風險決策研究表明, 正負情緒對風險偏好的影響各異。盡管相關理論和實證研究(Isen amp; Patrick, 1983; Johnson amp; Tversky, 1983; Prietzel et al., 2020)對此影響尚未達成共識, 但情緒效價的作用不容忽視。鑒于雙相障礙的心境階段與情緒效價緊密相關, 心境階段在風險決策研究中顯得尤為重要。然而, 當前研究常忽視心境階段的影響, 將不同心境階段患者混合成組與健康個體比較, 這可能導致因心境階段分布不同而導致結果產生偏差。如, Bauer等人(2017)選取30個緩解期患者、44個抑郁期患者和11個lt;輕gt;躁狂期患者形成患者組, 發現患者與健康個體在IGT任務中的風險偏好無差異; Malloy-Diniz等人(2009)則選取20個緩解期患者、10個抑郁期患者和9個lt;輕gt;躁狂期患者形成患者組, 同樣選用IGT任務, 卻發現患者比健康個體更偏好風險尋求。

盡管有研究區分雙相患者的心境階段, 但大多選取緩解期患者, 對發病期患者的探究相對較少。而且, 鮮有同一個研究直接比較不同心境階段患者的風險偏好差異(僅4篇該類文獻納入后續元分析; Adida et al., 2011; Thomas et al., 2007; 魏格欣 等, 2018; Yechiam et al., 2008), 且研究結果也不一致。例如, Adida等人(2011)比較躁狂期、抑郁期和緩解期患者與健康個體的IGT任務表現, 結果發現, 不同心境階段患者均比健康個體顯著更多選擇不利卡牌即更偏好風險尋求, 但是各個心境階段間的差異并不顯著(躁狂期:Cohen’s d"= 0.68; 抑郁期:Cohen’s d"= 0.59; 緩解期:Cohen’s d"= 0.35)。同樣是比較3個心境階段患者和健康個體的差異, Thomas等人(2007)發現不同心境階段患者比健康個體在RSQ量表冒險維度上的得分都顯著更高, 即更偏好風險尋求, 其中躁狂期患者的偏好程度顯著大于抑郁期和緩解期患者。而同樣采用IGT任務的Yechiam等人(2008)和魏格欣等人(2018)卻沒有發現發病期、緩解期和健康個體的差異。據此, 不同心境患者的風險偏好可能并不一致, 但由于研究量少、樣本小, 其結論可靠性仍需檢驗。故此, 本研究采用元分析的方式, 選擇心境階段為潛在調節變量, 以探究不同心境階段患者的風險偏好方向和程度是否有所差異。

1.2""測量特征的調節作用

雙相患者的風險偏好可能在不同測量特征下存在差異。以往研究主要采用3種測量類型來評估個體的風險偏好(Frey et al., 2017)。首先, 早期被廣泛使用的測量類型是借助自陳量表中的態度題目來評估即風險態度量表。這類題目既涵蓋抽象層面(如“我經常做冒險的決定”, Zhang et al., 2019), 也涉及特定情境(如“你有多大可能性用一天的收入來賭某一項體育賽事”, Blais amp; Weber, 2006)。然而, 這種測量類型雖簡便, 卻易受社會贊許性、記憶偏差的影響, 且難以進行動態評估。基于此, 研究者開發出了一系列行為實驗任務。常見的有風險選擇任務(Risky Choice Task, RC tasks), 即個體在低風險低收益選項和高風險高收益選項間選擇的決策對任務; 決策對相關變式, 如幸運輪盤任務(Wheel of Forture, WOF; Mellers et al., 1999)和PD任務(Richards et al., 1999); 動態賭博任務, 如IGT任務、CGT任務等; 以及更具現實模擬性的任務, 如BART任務、釣魚風險任務(Angling Risk Tasks, ART; Pleskac, 2008)等。這些任務雖規避了量表的局限, 但多聚焦經濟結果, 生態性有限, 與真實風險決策有一定差距(Fischhoff amp; Broomell, 2020)。第三種測量類型常見于臨床和流行病學研究, 直接觀察和記錄個體真實發生的日常風險行為(如, “你一天抽多少支煙”)。目前研究多關注健康領域的風險行為。如, 美國疾控中心的青年風險行為檢測系統(Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System, YRBSS)涵蓋了非故意傷害行為、煙草使用、酒精和其他物質使用、與意外懷孕和性傳播感染有關的性行為、不健康飲食和缺乏鍛煉等6種風險行為(Brener et al., 2004)。我國疾控中心也有類似調查, 其保留了YRBSS的后3種行為, 并將前3種行為調整為4種行為, 即導致非故意傷害的行為、導致故意傷害的行為、物質成癮行為和精神成癮行為(含網絡成癮、賭博成癮等) (季成葉, 2007)。此外, 過往對風險行為的元分析也多關注物質使用、性風險行為、危險駕駛、賭博等行為(如Roberts et al., 2021; Tinner et"al., 2018)。據此, 本研究將重點關注上述研究涉及的典型日常風險行為, 包括物質使用、性風險行為、不健康飲食、缺乏鍛煉以及非故意傷害行為中的危險駕駛行為等。

然而, 當研究者采用不同的風險偏好測量類型時, 其結果可能存在差異。Frey等人(2017)采用3種測量類型39個測量指標評估1507名個體的風險偏好。結果發現, 風險態度量表與日常風險行為的關聯性較強, 而行為實驗任務與這兩者的關聯性較弱。這提示我們, 采用單一測量類型判斷雙相患者的風險偏好可能會導致研究結論因測量工具的局限而產生偏差。如, Hart等人(2019)發現雙相患者在PD任務中的折扣率顯著大于健康個體即更偏好風險規避, 但在抽煙行為上卻明顯高于健康個體。這也凸顯了不同測量類型下雙相患者風險偏好的復雜性。事實上, 不僅跨測量類型的結果有差異, 即便采用同一種測量類型, 不同風險態度量表、行為實驗任務或日常風險行為間的結果也可能不同。如, Edge等人(2013)采用IGT任務發現緩解期患者比健康個體更偏好風險尋求, 而Wong等人(2021)在BART任務中卻發現緩解期患者比健康個體更偏好風險規避。即便是同一研究, 選用不同任務或行為也會造成結果差異。如, Ibanez等人(2012)同時采用IGT任務和理性風險決策任務(Rational Decision-"Making Under Risk, RDMUR)比較雙相患者與健康個體的風險偏好, 但僅在IGT任務中發現患者比健康個體更偏好風險尋求; Di Nicola等人(2010)發現, 同樣測量日常風險行為, 雙相患者比健康個體在病態賭博、過度消費、工作成癮和性成癮方面的行為頻率顯著更高, 在網絡成癮方面顯著更低, 而在運動成癮方面無差異。可見, 不同測量類型甚至同種測量類型中不同量表、任務或風險行為都可能造成結果矛盾, 這可能和測量內容有關(如選取不同領域、不同性質的行為)。因此, 我們有理由認為, 采用單個測量類型來比較雙相患者與健康個體風險偏好的研究結論可能難以全面反映個體的風險偏好。也因此, 本研究擬將測量特征(如測量類型、任務類型等)作為潛在調節變量, 檢驗不同測量特征下雙相患者與健康個體的風險偏好差異有無變化。

1.3""人口學特征的調節作用

值得關注的是, 樣本的人口學特征差異也可能導致雙相患者風險偏好的研究結果不一致。Byrnes等人(1999)的元分析揭示, 在14種風險決策測量(共16種)中, 男性均比女性更偏好風險尋求。日常觀察亦發現, 相較男性, 女性對風險事件更敏感(Paluckait? amp; ?ardeckait?-Matulaitien?, 2017), 更厭惡風險(Croson amp; Gneezy, 2009), 更少做出風險行為(Charness amp; Gneezy, 2012; Dir et al., 2014)。雙相患者中, 性別與風險偏好的關系同樣值得探討。研究表明, 男女雙相患者在臨床癥狀上存在差異(Benazzi, 2003)。如, 女性更易抑郁, 自殺意圖高, 容易出現進食、焦慮等問題; 而男性更易躁狂, 伴隨酗酒和其他物質濫用問題(Azorin et al., 2013)。然而, 這些癥狀差異是否意味著風險偏好的不同尚不清晰, 因此不同性別的患者與健康個體的風險偏好差異是否不同仍需探究。本研究旨在探討女性占比對雙相患者與健康個體風險偏好差異的影響, 以檢驗性別的調節作用。若雙相患者存在與健康個體相似的性別差異, 那么女性占比的增加可能會減少兩者的風險偏好差異; 反之, 若這一性別差異消失或逆轉, 則兩者的風險偏好差異可能會隨女性占比增加而擴大。

年齡對風險偏好的影響也值得關注。研究表明, 相較青少年, 成年人常表現出更低的風險尋求(Defoe et al., 2015; Josef et al., 2016)。然而, 這一趨勢在雙相患者中是否存在值得探究。雙相患者常伴有認知功能損害(Bora et al., 2009), 且隨著年齡增長, 這種損害可能加劇(John et al., 2019; Lewandowski et al., 2014), 因而可能導致老年患者做出更多非理性的風險決策。另一方面, 雙相障礙的發病年齡較早(Bolton et al., 2021), 超過六成患者在21歲前發病(Duffy, 2009)。青少年和成年早期患者常面臨混合癥狀、病程長和共病障礙多等問題, 這可能對其正常發育和社會心理功能造成較大影響, 繼而增加了他們自殺、物質濫用、學業問題等風險(Birmaher, 2013)。據此推測, 年輕患者也可能更偏好風險尋求。可見, 目前研究對雙相患者的年齡如何影響其風險偏好尚存爭議, 因而雙相患者與健康個體的風險偏好差異如何受年齡影響不得而知。若年齡對雙相患者和健康個體的風險偏好的影響趨勢相似, 那么兩者的風險偏好差異就可能隨年齡增大而減小; 反之, 若該影響趨勢減弱甚至方向相反, 那么兩者的風險偏好差異則可能隨年齡增大而擴大。因此, 我們將年齡作為潛在調節變量, 探究其是否影響雙相患者與健康個體的風險偏好差異。此外, 根據元分析需要, 本研究還將納入樣本受教育程度和所屬地區作為潛在調節變量。

綜上所述, 雙相患者的風險偏好與健康個體是否存在差異以及差異的方向和程度需要進行系統性梳理。雖然有研究者對2019年前發表的雙相障礙和風險決策關系的研究開展過元分析(Edge et al., 2013; Ramírez-Martín et al., 2020; Richard-Devantoy et al., 2016), 但Edge等人(2013)和Richard-"Devantoy等人(2016)的元分析僅納入了采用IGT任務的研究結果, 不足以全面反映雙相患者的風險決策特征。因此, 本研究將納入多種風險偏好測量類型的研究(即風險態度量表、行為實驗任務和日常風險行為等)。再者, 此前元分析納入的研究樣本幾乎全部來自西方國家(Ramírez-Martín et al., 2020), 且主要關注緩解期患者(Edge et al., 2013)或有無自殺行為的患者(Richard-Devantoy et al., 2016), 因而結果的泛化性和可靠性都待檢驗。因此, 本研究將基于更全面的最新文獻檢索結果(6個數據庫中截至2024年4月的文獻), 將風險決策測量特征(測量類型、任務類型、任務明確性和領域類型)、患者心境階段(緩解期、抑郁期和lt;輕gt;躁狂期)、樣本人口學特征(性別、年齡等)等納入元分析, 再次探索雙相障礙和風險決策的關系, 并檢驗測量特征、心境階段、人口學特征等的調節。

2 "方法

本研究已在PROSPERO平臺進行預注冊, 預注冊編號為CRD42022346204。

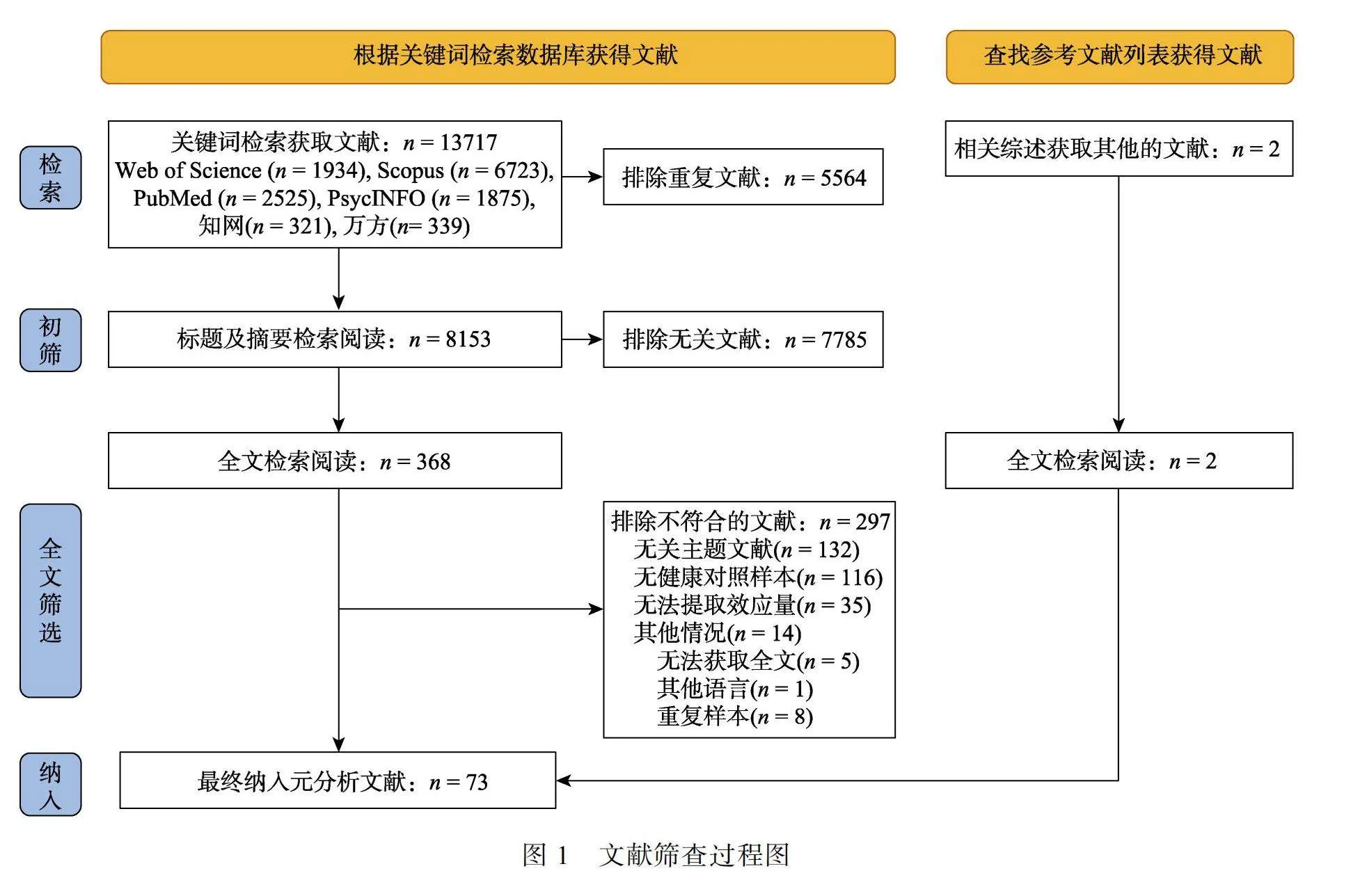

2.1 "文獻檢索

文獻檢索涵蓋中英文獻, 檢索時間自數據庫建立至2024年4月15日。中文文獻檢索使用中國知網和萬方兩個數據庫, 而英文文獻檢索使用Web of Science、PubMed、Scopus和PsycINFO四個數據庫。同時本研究還采用文獻回溯法, 從相關元分析和綜述的參考文獻中篩選論文以查漏補缺。基于研究主題, 文獻檢索選擇與“雙相”和“風險決策”相近或相關的中英文詞匯為檢索關鍵詞。中英文檢索詞都由4類詞匯組成:(1)雙相障礙相關詞匯; (2)風險決策相關詞匯; (3)常見風險決策范式名稱; (4)常見日常風險行為名稱(具體檢索詞見網絡版附表1)。

2.2""文獻納入與排除標準

文獻納入標準同時包括:(1)包含以雙相障礙為主要診斷的患者組; (2)包含未有任何精神病學診斷的健康對照組; (3)包含風險決策的測量(風險態度量表、行為實驗任務或者日常風險行為)。在全文篩選階段實施的其他標準包括:(4)有明確的診斷標準(如, DSM-V); (5)研究提供足夠數據計算效應量(如平均數、標準差和樣本量等)。如果發現未報告可轉換指標的研究, 我們嘗試通過在已發表的雙相

障礙與風險決策的元分析(Edge et al., 2013; Ramírez-Martín et al., 2020; Richard-Devantoy et al., 2016)中查找獲得相關數據, 若仍無法獲得則排除該研究。最終Yechiam等人(2008)的效應量數據從Edge等人(2013)的元分析中獲取; (6)數據重復僅保留其中一篇, 如會議摘要以論文形式發表在學術期刊并且報告相關數據, 則以正式發表的學術論文為準, 反之采用會議摘要里的數據。

如圖1所示, 文獻篩查包括了檢索、初篩、標題/摘要篩選和全文篩選4個階段。兩名評價者(本文的第1和第2作者)依據納入標準進行篩查, 確定最終納入元分析的文獻。本研究按上述標準檢索出8153篇文獻, 其中7785篇在標題和摘要篩選時被排除。對剩余368篇文獻進行全文篩選, 最終納入71篇文獻。同時, 我們從相關綜述和元分析的參考文獻列表中又發現并納入了2篇文獻。因此, 本研究最終納入73篇文獻。其中, 符合要求的中文文獻有4篇, 英文文獻有69篇。

2.3""數據提取與質量評價

本研究的兩位作者對納入元分析的文獻獨立提取所需數據, 在提取過程中主要遵循以下原則:(1)如果一篇文獻同時報告多個獨立樣本, 則需提取各個樣本的數據; (2)如果文獻在不同被試特征(如有無自殺行為或不同心境階段)中均報告對應均

值和標準差, 則需提取各個特征樣本的數據; (3)如果對風險偏好有多個測量指標, 則需提取每個測量指標對應的數據。若出現兩名作者提取的數據不一致時, 則需經過討論并查閱原始文獻確定最終提取方案。本研究需提取的數據變量如下:

(1)基本信息

文獻信息(第一作者和發表年份)和效應量數量。

(2)樣本特征

a)樣本量

b)年齡:提取文獻中各個組別的平均年齡(標準差)。

c)性別比:提取文獻中各個組別的男女人數或性別比, 最終都轉換成女性占比。

d)受教育程度:考慮到納入文獻大多采用受教育年限來反映受教育程度, 所以本研究提取文獻中各個組別的受教育年限。若文獻未報告該指標, 本研究將其標為缺失值。

e)所屬國家及地區:提取文獻中樣本所屬國家, 并根據國家所在地區進行標注(如, 歐洲、北美洲、亞洲等)。

f)心境階段:提取文獻中樣本當時所處的心境階段(緩解期、lt;輕gt;躁狂期和抑郁期)。若文獻未報告心境階段或將不同心境的患者混為一組比較, 本研究將其標為缺失值。

g)診斷標準:提取文獻中用于判斷樣本患病與否的診斷標準。

h)抑郁/躁狂程度:提取文獻中樣本的抑郁/躁狂程度(均值和標準差)及其量表名稱。

(3)測量特征

a)測量類型:提取文獻中所涉及的風險偏好測量類型名稱(風險態度量表、日常風險行為、行為實驗任務)和所有反映風險偏好的指標名稱。

b)風險決策:提取文獻中樣本在所有風險決策指標上的表現(均值和標準差)。

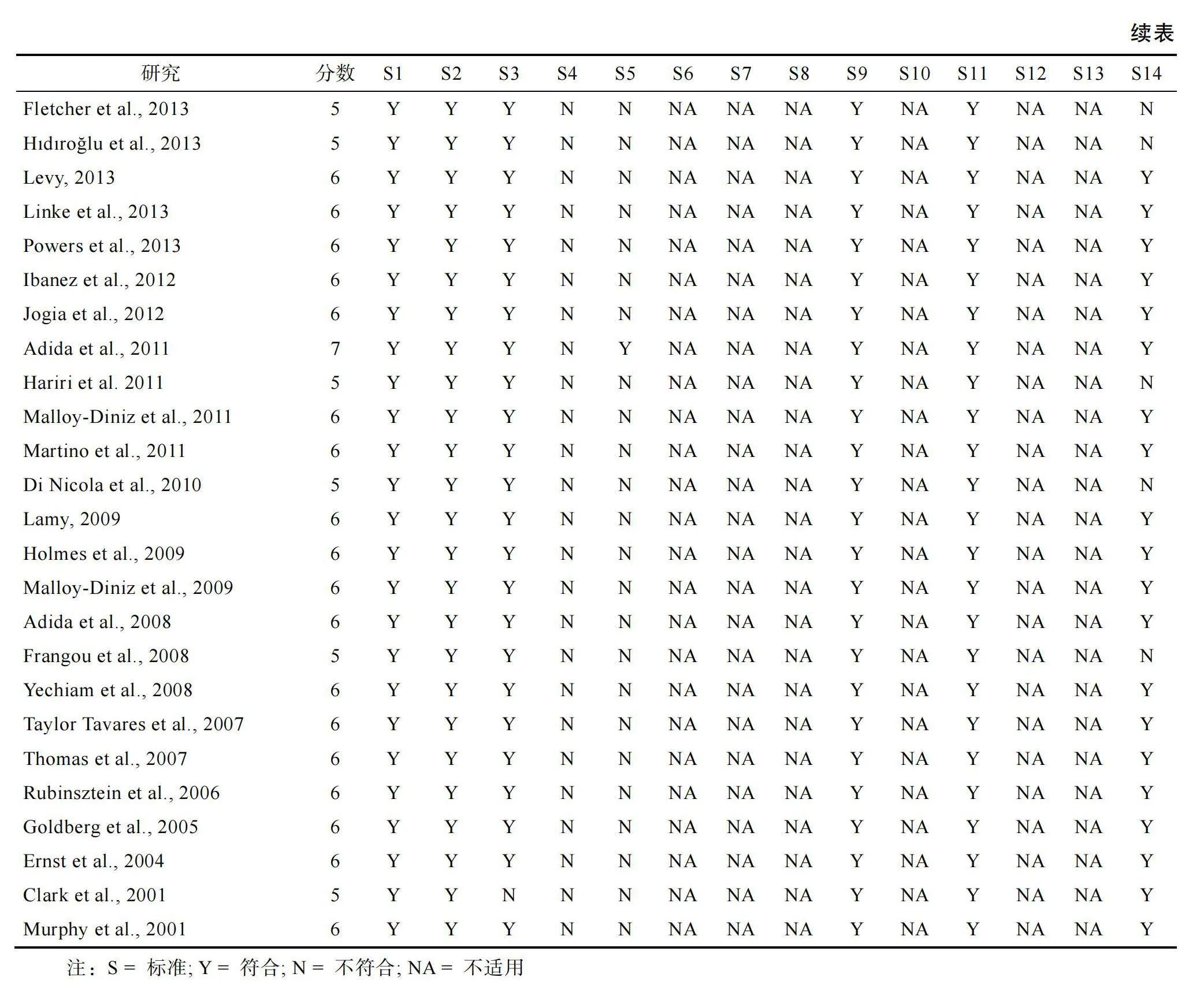

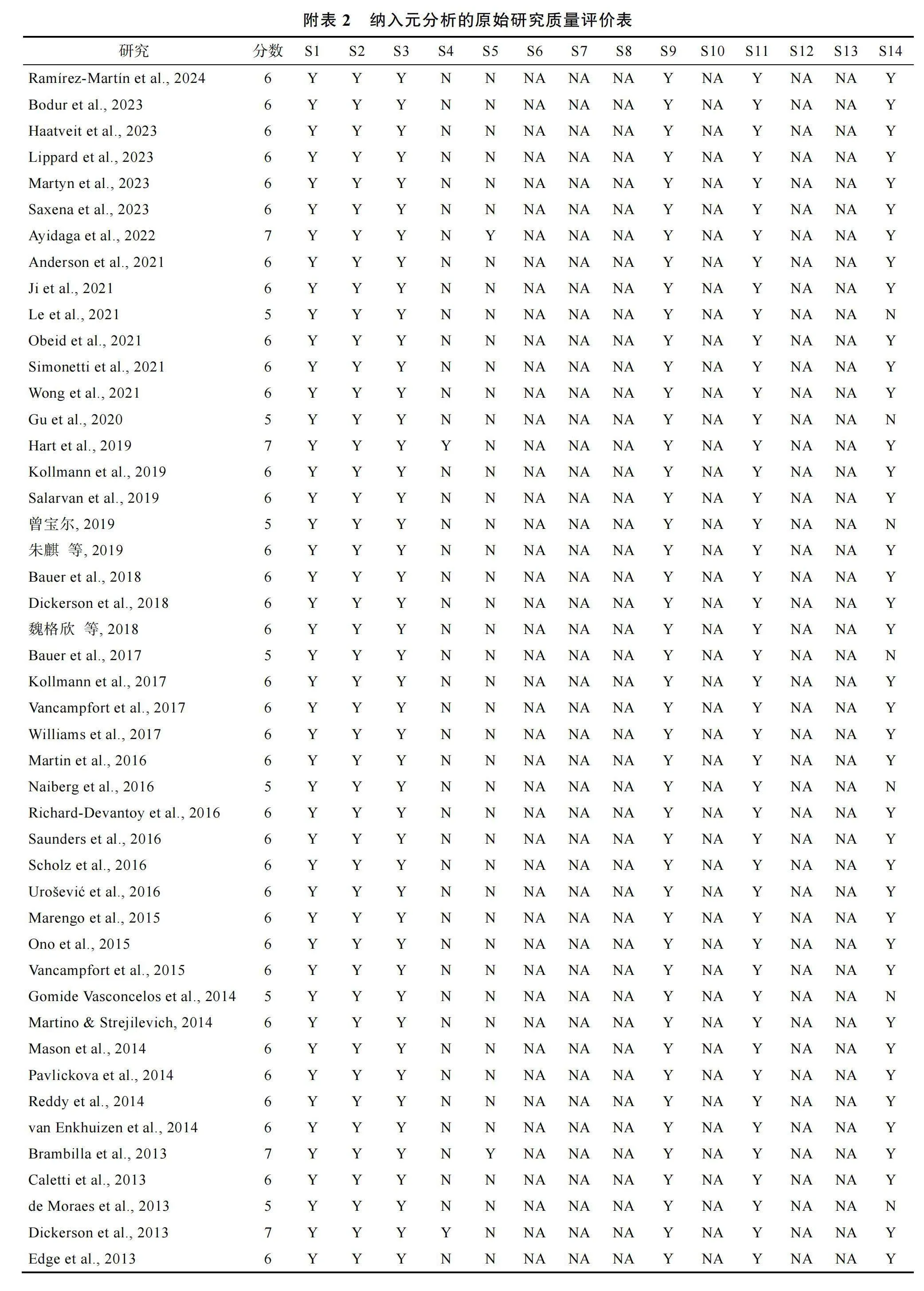

本研究還將對納入的每篇文獻進行質量評分。研究者根據美國國立衛生研究院(National Institutes of Health, NIH)的縱向和橫斷研究質量評估工具(Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies)的標準進行評估, 其中符合標準計1分, 不符合標準則計0分(National Institutes of Health, 2014)。橫斷研究的質量評分介于0~8之間, 縱向研究的質量評分則介于0~14之間。研究質量評分結果見網絡版附表2, 評分越高說明文獻質量越高。

2.4""統計分析

本研究使用R 4.3.2的metafor程序包(Viechtbauer, 2010)統計分析, 計算雙相患者與健康個體間的風險偏好差異, 并以Hedges' g作為效應量指標。g值采用雙相患者在風險決策測量指標中的表現減去健康個體的表現, 但在某些風險決策測量類型中不同指標的大小對應的風險偏好不同。例如, IGT任務的測量指標為凈分數, 個體凈分數越大表明其越偏好風險規避, 此時g值為正表明雙相患者比健康個體更偏好風險規避; 而BART任務的測量指標為調整后平均充氣次數, 個體充氣次數越多則表明其越偏好風險尋求, 此時g值為正表明雙相患者比健康個體更偏好風險尋求。因此, 不同測量類型中g值為正有2種截然相反的含義, 所以本研究對效應量進行統一編碼, 使g值為正表示雙相患者比健康個體更偏好風險尋求, g值為負則表示更偏好風險規避。如果文獻報告了其他可轉換為效應量的數據(如, t值), 將通過R軟件的esc程序包將其轉換為Hedges' g"(Lüdecke, 2019)。

目前納入文獻報告的雙相患者與健康個體風險偏好差異的Hedges' g從?2.82至2.98, 結果差異較大。為了避免極端值對研究結論的影響(Kepes amp; Thomas, 2018), 本研究參考過往的元分析研究(如Fernandes amp; Garcia-Marques, 2020; Kathawalla amp; Syed, 2021), 選擇剔除大于和小于所有效應量的均值或中位數3個標準差的單個效應量。研究共剔除4個效應量(Rai et al., 2018; Richard-Devantoy et al., 2016 lt;第2個效應量gt;; Saxena et al., 2023 lt;第2個效應量gt;; 朱承剛, 2020), 最終有71篇文獻納入后續元分析。

在本研究中, 部分被納入的文獻報告了多個可能存在相關的效應量。其中, 出現多個效應量的主要原因包括以下三方面:(1)文獻使用多種測量工具評估風險決策; (2)文獻報告了多個風險決策評價指標; (3)文獻選取多個臨床樣本(如, 緩解期患者和lt;輕gt;躁狂期患者)。此時如若使用嵌套效應量分析, 則違反傳統元分析效應量間相互獨立的假設。但若不考慮效應量間的關聯性, 則會使結果產生偏差(Assink amp; Wibbelink, 2016)。因此, 我們采用三水平隨機效應模型并選擇了限制性最大似然方法來估計模型結果。相比傳統的元分析方法, 該模型考慮了效應量間的相關性, 既最大化地保留了信息, 又具有更高的統計檢驗力(Cheung, 2014)。

2.4.1""異質性分析

本研究采用Cochran’ Q檢驗和I2統計量來檢驗和評價研究間的異質性。Q檢驗判斷觀測到的效應量間的變異性是否大于研究的抽樣誤差。若Q檢驗的結果顯著, 則數據呈現異質, 反之則同質。而I2統計量衡量的是可歸因于異質性而非抽樣誤差造成的研究間效應量變異在總變異中所占百分比, I2越大, 異質性越明顯。25%、50%和75% 分別表示異質性的低、中、高。此外, 三水平隨機模型涉及三種不同的方差來源, 包括觀察到的效應量的抽樣方差(水平1), 同一研究中不同效應量間的方差(水平2)以及不同研究間的方差(水平3)。本研究將進一步估計抽樣方差、研究內方差和研究間方差, 并對研究內和研究間方差進行對數似然比檢驗, 以確定其是否顯著。當研究異質性較高且研究內和研究間方差顯著時, 則需檢驗調節效應以確定異質性的來源(Gao et al., 2017)。

2.4.2""發表偏差檢驗

發表偏差是指已發表文獻不能全面代表該主題已完成的研究總體的現象, 它往往與有統計學意義的研究結果更易發表而不顯著或效應量較小的研究結果較難發表有關。為了控制發表偏差, 本研究不僅納入已出版的期刊論文, 還納入了暫未出版的學位論文和會議論文。同時, 本研究采用漏斗圖和Egger-MLMA回歸檢驗發表偏差。當效應量間并非相互獨立時, 相較于傳統Egger檢驗, Egger-"MLMA回歸更能有效控制I類錯誤(Rodgers amp; Pustejovsky, 2020)。如若存在顯著的發表偏差, 漏斗圖將呈現不對稱的現象, 同時Egger-MLMA檢驗結果也會顯著。如果存在顯著的發表偏差時, 則需要采用剪補法(Trim and fill method)進一步檢驗和校正(Duval amp; Tweedie, 2000)。

2.4.3""調節效應分析

本研究預期效應量間可能存在較高的異質性, 為具體分析變異的來源, 將對隨機效應模型進行調節效應分析。為了避免相互關聯的調節變量造成的多重共線性問題, 本研究將進一步納入所有顯著的調節變量進行多調節變量分析(Multiple-moderator Model) (Hox et al., 2010)。

(1)樣本特征

大多數研究匹配了雙相患者與健康個體的人口學特征, 因此本研究選取雙相患者的人口學特征為調節變量, 包括年齡、性別、受教育程度, 地區(1 = 歐洲, 2 = 北美洲, 3 = 南美洲, 4 = 亞洲)和患者所處心境階段(1 = 緩解期; 2 = lt;輕gt;躁狂期; 3 = 抑郁期)。

(2)測量特征

基于過往研究對風險決策測量類型的分類(Frey et al., 2017), 本研究在納入的文獻中區分了3種測量類型, 以考察雙相障礙對風險決策的影響是否因測量類型的不同而不同。具體編碼為:1 = 風險態度量表; 2 = 行為實驗任務; 3 = 日常風險行為。值得注意的是, 風險態度量表聚焦個體的一般性風險態度或在特定領域的風險態度, 而日常風險行為則聚焦個體真實發生的風險行為。

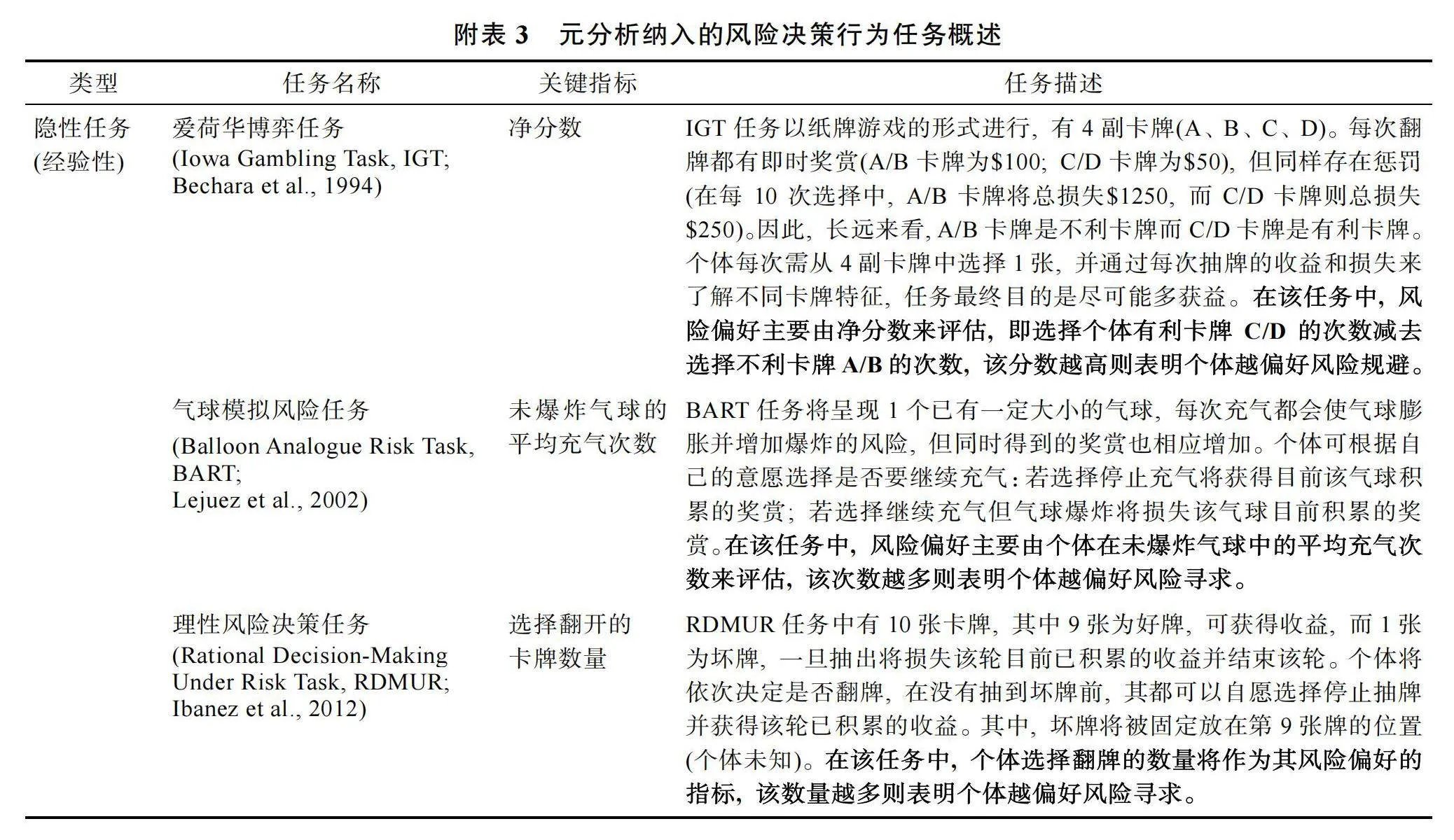

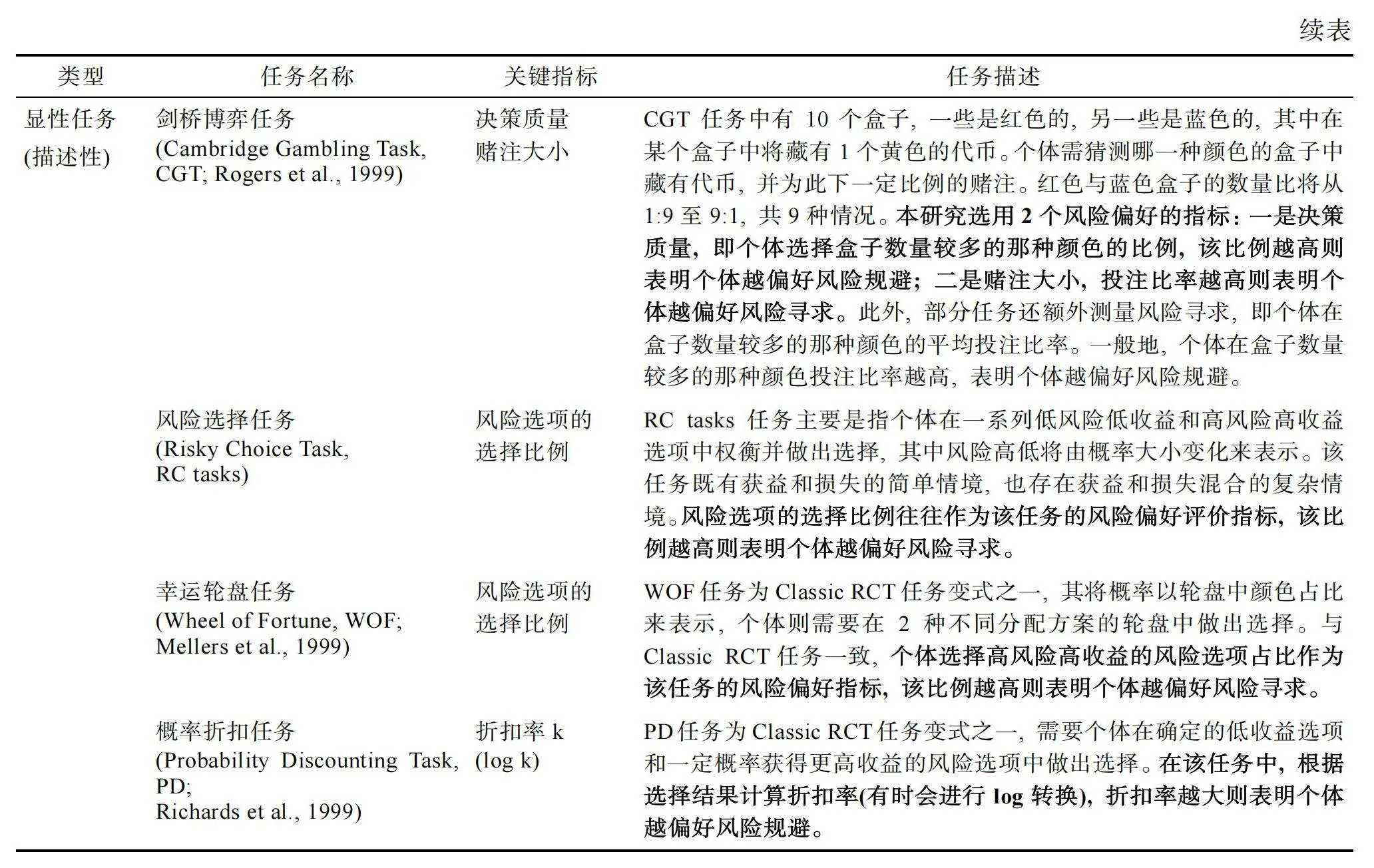

行為實驗任務特征:研究選取任務類型為調節變量。在行為實驗任務的文獻中, 除了IGT任務、BART任務和CGT任務外, 剩余任務均為風險選擇任務(RC tasks)及其變式(具體介紹見網絡版附表3)。據此, 將任務類型編碼為1 = IGT; 2 = BART; 3"= CGT; 4 = RC tasks。此外, 研究者還根據事件概率和結果是否已知將風險決策任務分為描述性和經驗性兩類(Hertwig et al., 2004), 前者指個體獲知所有選項的信息, 包括獎賞大小和概率高低, 如CGT任務, 而后者指個體未被告知具體概率等信息而需通過任務反饋進行學習, 如IGT任務。本研究參考Dekkers等(2016)采用任務明確性來區分這2種任務, 1 = 顯性任務(對應描述性決策任務), 2 = 隱性任務(對應經驗性決策任務)。

日常風險態度和行為特征:基于前人對風險決策領域的劃分(Blais amp; Weber, 2006; Butler et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2016)以及本研究納入文獻所涉風險行為的領域歸屬情況, 本研究將風險行為所屬領域分為1 = 健康; 2 = 經濟; 3 = 總體態度, 并將領域類型作為調節變量。其中, 部分態度和行為反映了個體的總體風險偏好并未聚焦于單一領域(如, “我在生活的很多方面都喜歡尋求風險。”), 因此本研究將該類態度和行為歸屬于“總體態度”。

3 "結果

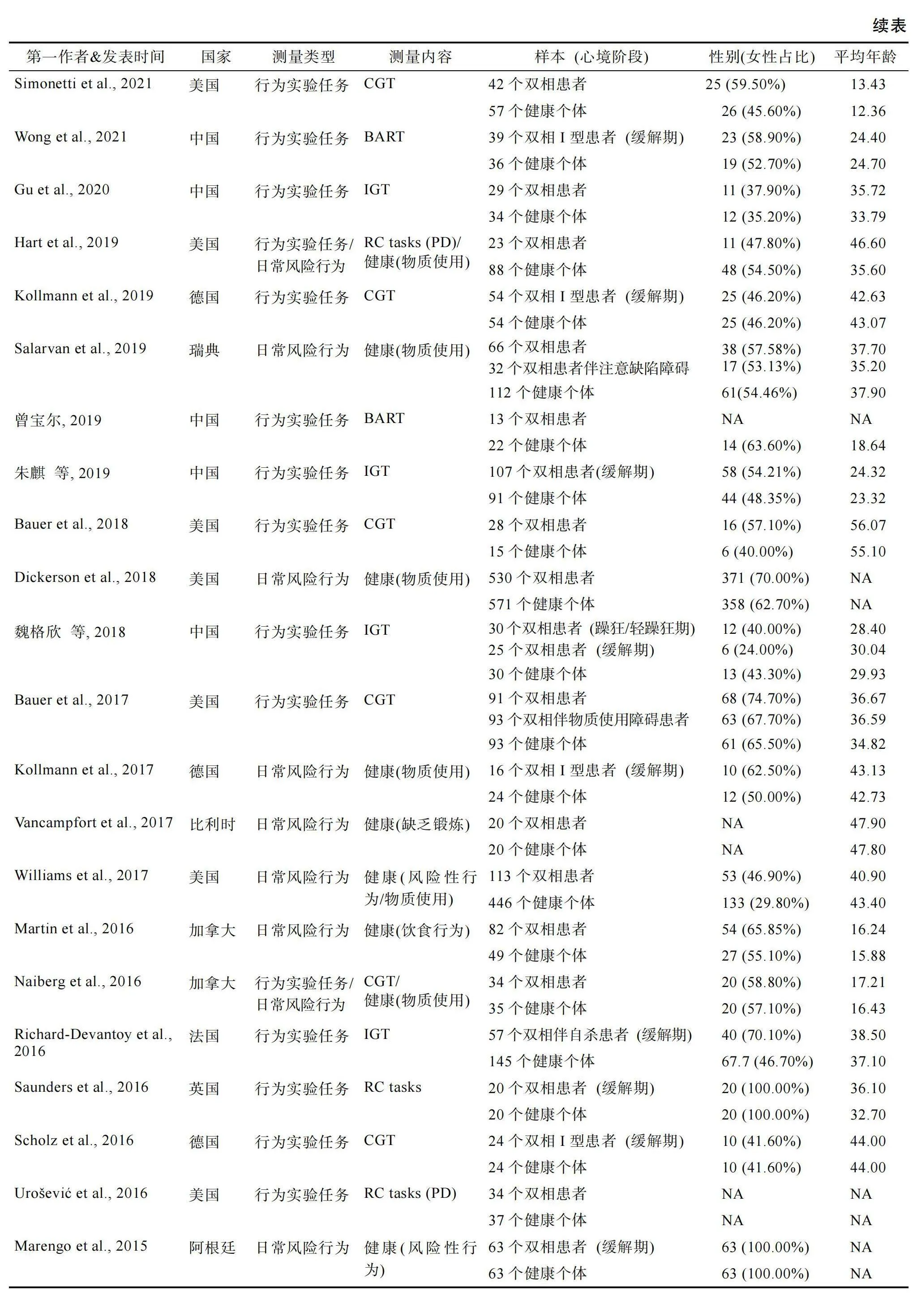

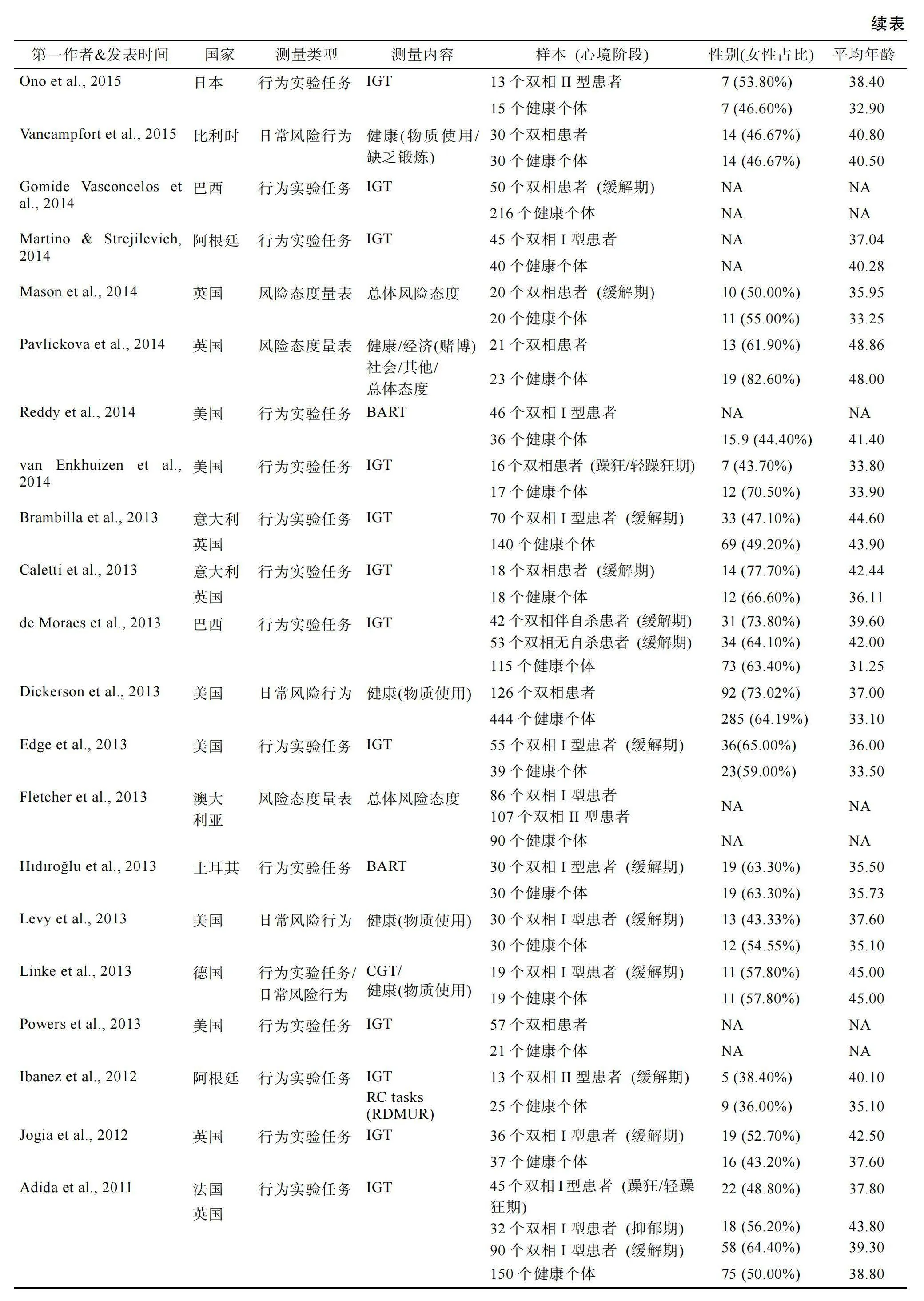

3.1""文獻特征

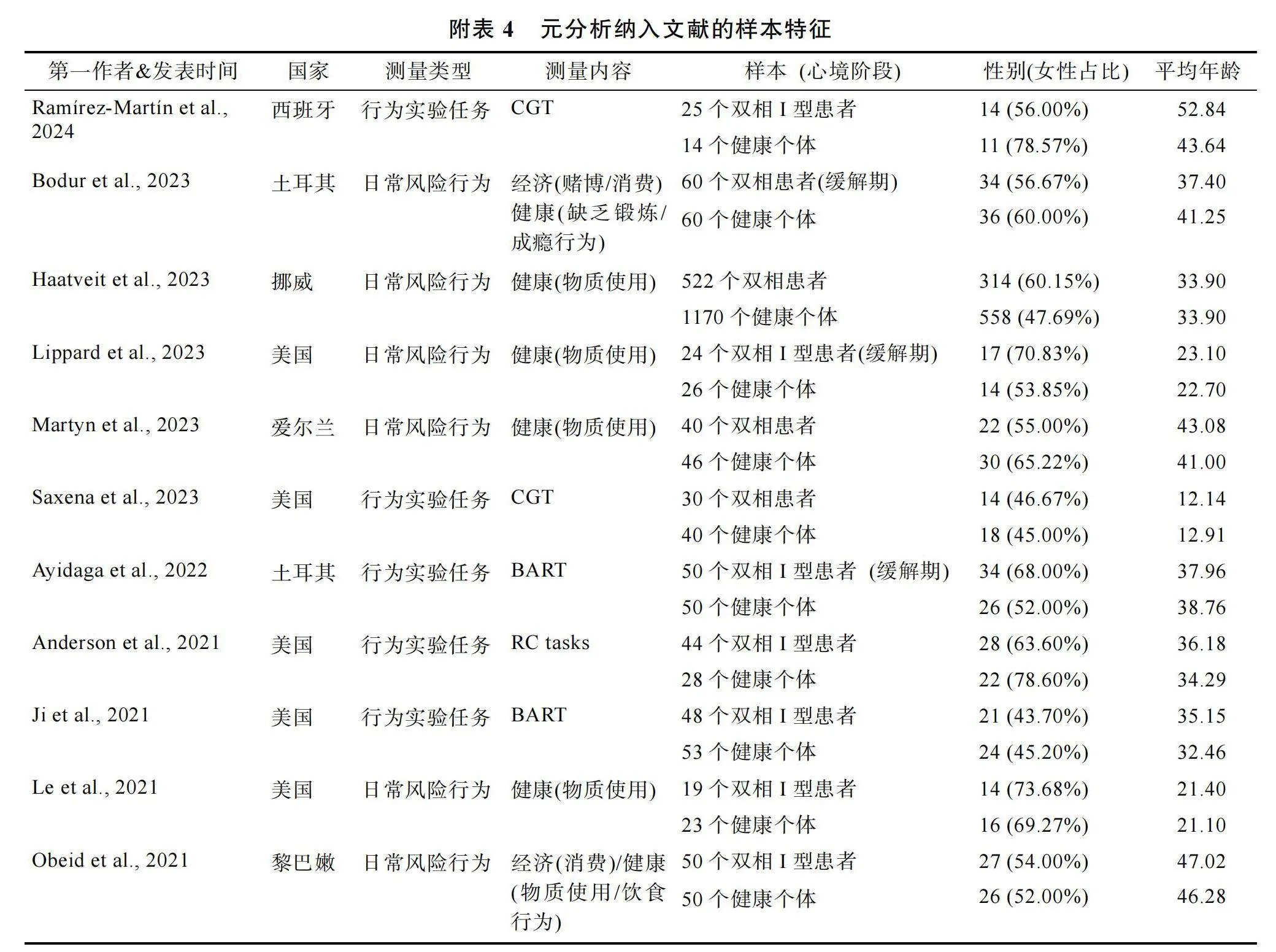

本元分析最終納入71篇符合標準的文獻, 中文文獻3篇, 英文文獻68篇。這71篇文獻包含176個效應量, 其中同一篇文獻中效應量數最多有9個, 最少的有1個。在納入的文獻中(見網絡版附表4), 有12篇發表于2001~2009年(16.90%), 45篇發表于2010~2019年(63.38%), 剩余14篇發表于2020~"2024年(19.72%)。文獻中被試來自歐洲(42.25%, n = 30)、北美洲(33.80%, n"= 24)、南美洲(11.27%, n"= 8)、亞洲(11.27%, n = 8)和大洋洲(1.41%, n"= 1)。所有納入的文獻均為橫斷研究。36篇文獻納入不同心境階段的患者并予以區分, 其中30篇納入緩解期患者, 8篇納入lt;輕gt;患者, 3篇納入抑郁期患者。在風險決策測量類型上, 有48篇文獻采用行為實驗任務, 其中23篇采用IGT任務, 8篇采用BART任務, 12篇采用CGT任務, 其余采用RC tasks任務。有5篇文獻采用風險態度量表, 報告被試對各個決策領域或總體的風險態度, 以及有22篇文獻報告被試真實的日常風險行為狀況, 包括物質使用、缺乏鍛煉、風險性行為等方面。

3.2 "總體模型

3.2.1 "主效應檢驗

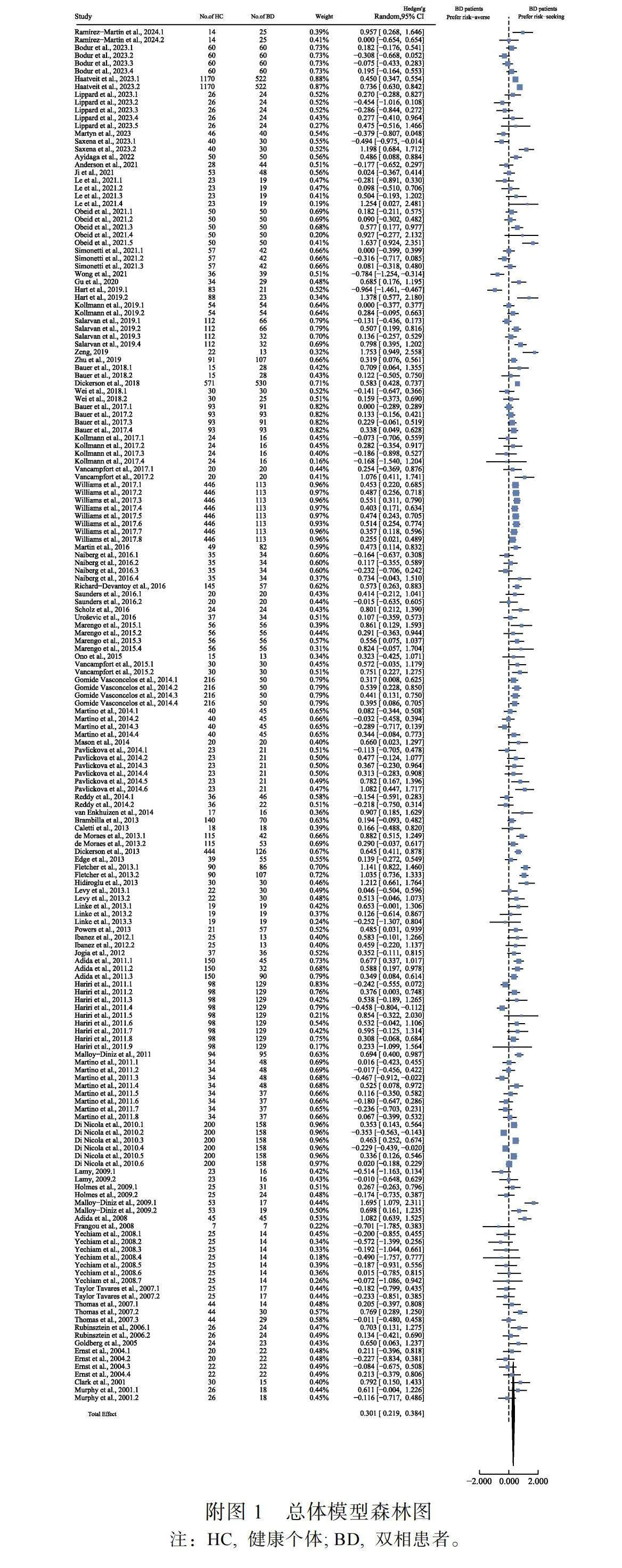

三水平隨機模型比較了雙相患者與健康個體在所有風險決策測量類型中的風險偏好是否存在顯著差異。結果發現(見網絡版附圖1), 總體效應量顯著(k = 176, Hedges' g"= 0.301, 95% CI [0.219, 0.384], t"= 7.21, p"lt; 0.001), 表明雙相患者(N"= 4574, Mage"= 36.43歲, 60.85%女性)比健康個體(N"= 5965, Mage"= 35.63歲; 53.47%女性)更偏好風險尋求。

3.2.2""異質性檢驗

對所有風險決策指標進行異質性檢驗。結果表明, 總體模型均存在高異質性(QE"(175) = 684.33, p"lt; 0.001, I2"= 77.25%)。進一步分析發現, 研究內方差(LRT = 75.98, p"lt; 0.001)和研究間方差(LRT = 9.20, p"= 0.002) 均顯著。在其總方差來源中, 抽樣方差、研究內方差和研究間方差分別為22.75%, 44.65%和32.60%。因此, 非常必要進一步分析調節變量以探究雙相障礙與風險決策的關系。

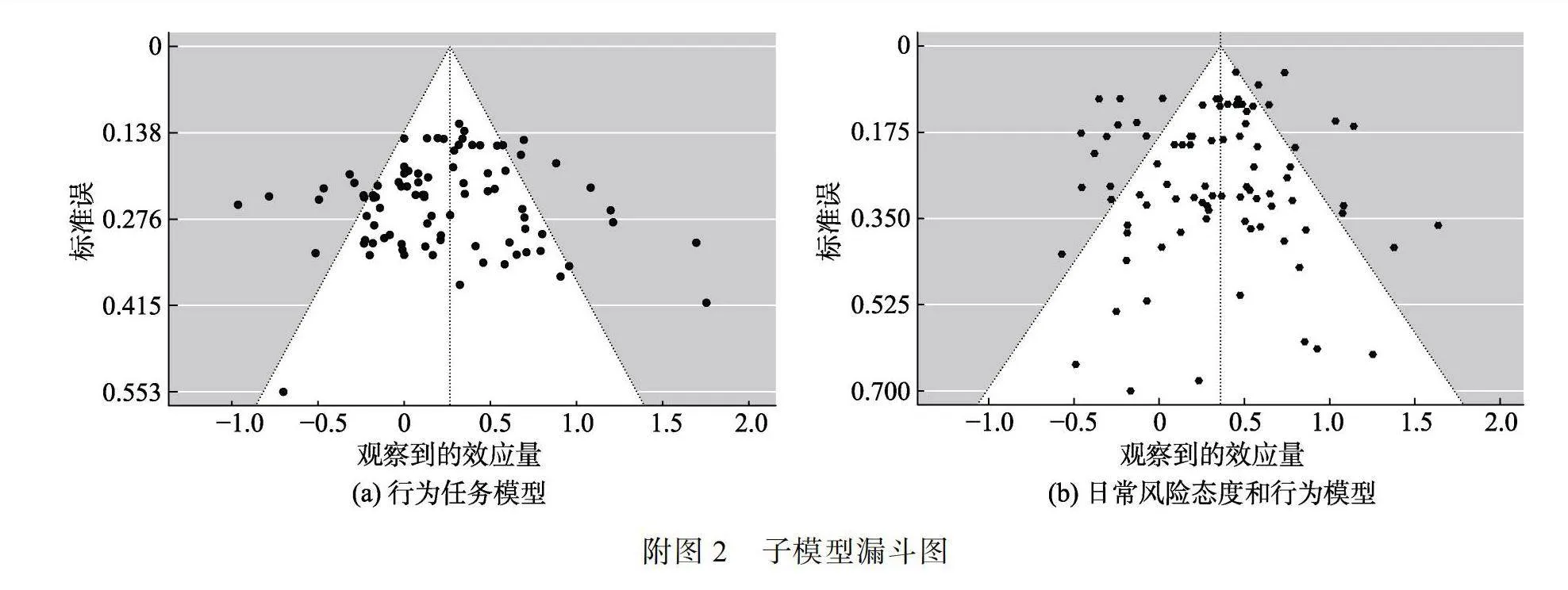

3.2.3 "發表偏差檢驗

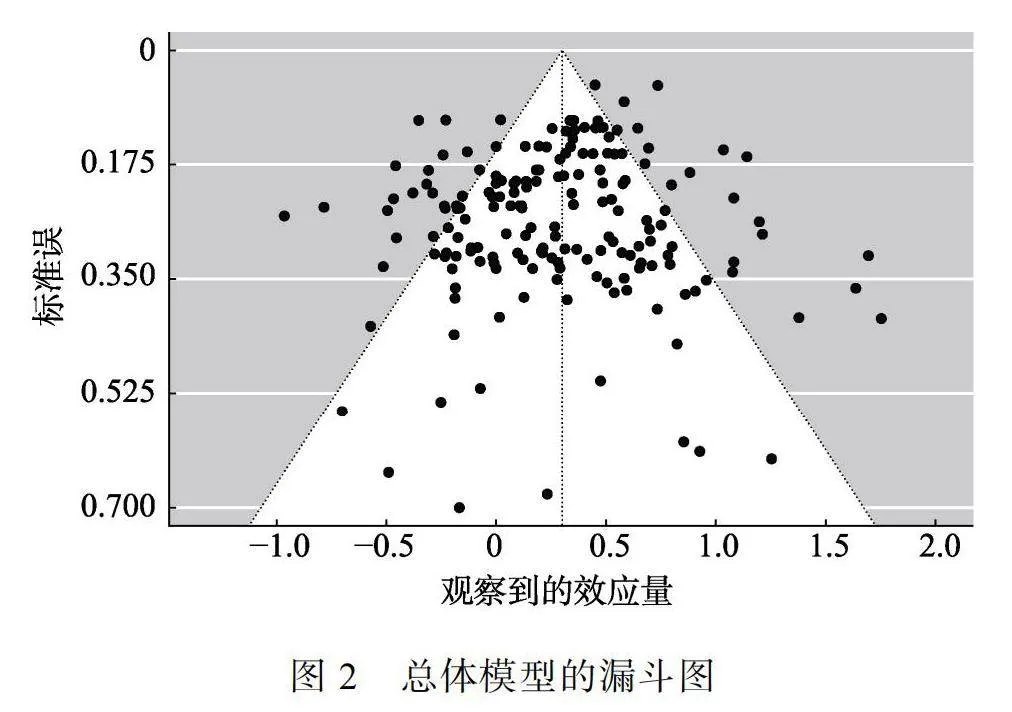

本研究采用漏斗圖和Egger-MLMA回歸以檢驗發表偏差。結果發現, 在漏斗圖上的每個效應量基本均勻分布在總體效應量兩側(見圖2), 且Egger-"MLMA回歸結果也不顯著(t"= 1.64, p"= 0.102)。由此說明當前模型沒有顯著的發表偏差, 繼而本研究無需采用剪補法進行校正。

3.2.4""調節效應檢驗

考慮到樣本具有高異質性, 本研究從樣本特征和測量特征兩方面選擇潛在的調節變量。樣本特征包含年齡、性別比、受教育程度、所屬地區和患者所處心境階段, 而測量特征則包含風險偏好測量類型、領域類型、行為實驗任務類型和任務明確性。同時, 研究還將進一步進行亞組分析得到各分類調節變量中各組的主效應和組間差異。

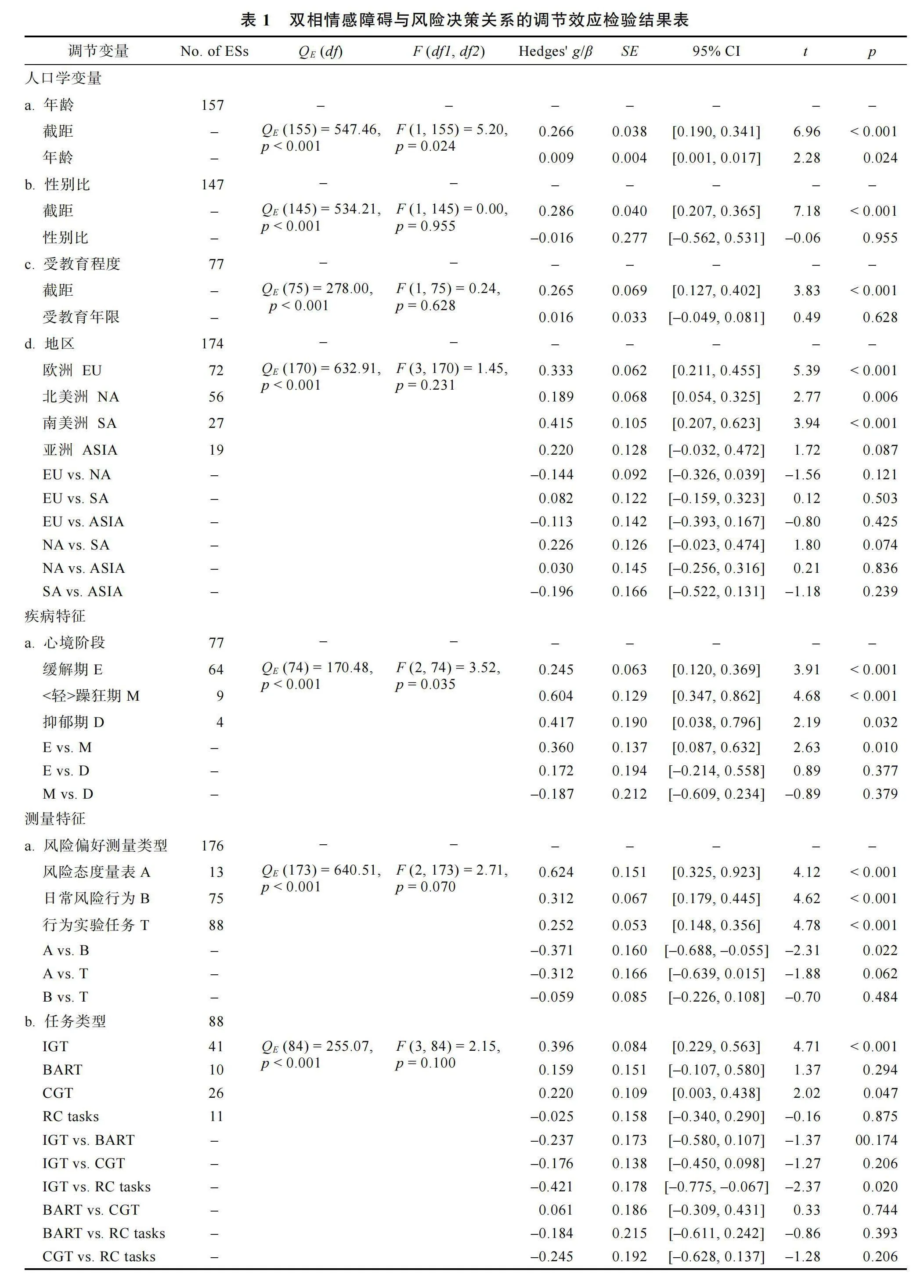

調節效應檢驗結果見表1。就樣本特征而言, 年齡的調節作用顯著(β"= 0.009, p"= 0.024), 即隨年齡增大, 雙相患者比健康個體偏好風險尋求的程度增加。心境階段的調節作用顯著(p"= 0.035), 以緩解期(Hedges' g = 0.245, p lt; 0.001)、lt;輕gt;躁狂期(Hedges' g = 0.604, p lt; 0.001)和抑郁期患者(Hedges' g = 0.417, p lt; 0.001)為樣本的效應量均顯著, 即不論心境階段如何, 患者均比健康個體更偏好風險尋求。其中, lt;輕gt;躁狂期的效應量顯著大于緩解期(β"= 0.360, p = 0.010)。雖然其他樣本特征的調節作用不顯著, 但在地區中部分亞組的效應量顯著。除了亞洲的效應量不顯著外(Hedges' g = 0.220, p = 0.087), 其余地區效應量均顯著(歐洲: Hedges' g"= 0.333, p lt; 0.001; 北美洲: Hedges' g = 0.189, p = 0.006; 南美洲: Hedges' g = 0.415, p lt; 0.001)。

就測量特征而言, 本研究未發現風險偏好測量類型顯著的調節作用(p"= 0.070)。不論采用風險態度量表(Hedges' g = 0.624, p lt;"0.001)、日常風險行為(Hedges' g = 0.312, p lt; 0.001)還是行為實驗任務(Hedges' g = 0.252, p lt; 0.001)的效應量都顯著。其中, 行為實驗任務與風險態度量表的效應量間存在顯著差異(β"= 0.371, p = 0.022), 其余效應量間差異不顯著。因此, 采用不同風險偏好測量類型探究雙相障礙與風險決策的關系時, 研究結果方向一致, 都表現為雙相患者比健康個體更偏好風險尋求, 但具體差異程度有所不同。風險態度量表效應量最大, 而行為實驗任務效應量最小。

在行為實驗任務中, 雖然研究未發現任務類型顯著的調節作用(p"= 0.100), 但采用IGT (Hedges' g"= 0.396, p lt; 0.001)和CGT任務(Hedges' g = 0.220, p = 0.047)的效應量顯著, 即患者在這2個任務中均比健康個體更偏好風險尋求, 且IGT任務的效應量顯著大于RC 任務(β"= 0.421, p = 0.020)。此外, 本研究還發現在隱性任務時, 患者也比健康個體更偏

好風險尋求(Hedges' g = 0.343, p lt; 0.001)。

在日常態度和行為中, 本研究包含健康和經濟領域的態度和行為以及總體態度。結果發現, 領域類型的調節作用不顯著(p"= 0.062), 但在健康領域(Hedges' g = 0.308, p"lt; 0.001)、經濟領域(Hedges' g"= 0.331, p = 0.036)和總體態度(Hedges' g = 0.733, p"lt; 0.001)中, 雙相患者的風險尋求程度均顯著高于健康個體。其中, 總體態度和健康領域間的效應量差異顯著(β"= 0.424, p = 0.019)。

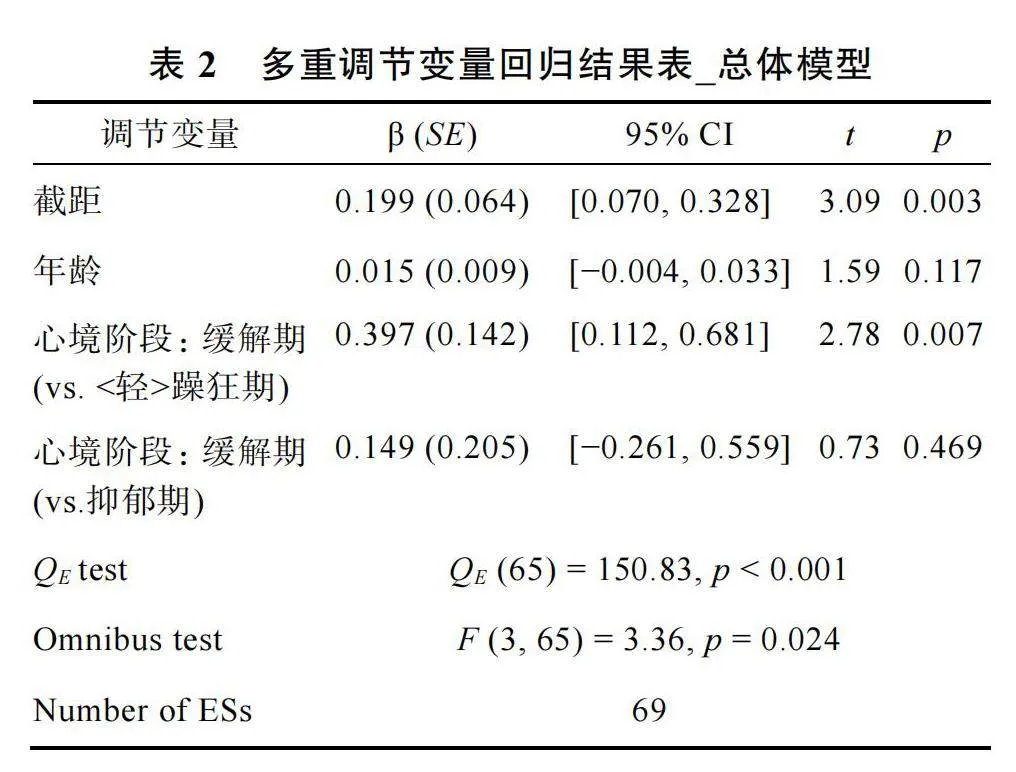

為了排除調節變量間的共線性, 根據Assink和Wibbelink (2016)的方法, 本研究納入所有顯著的調節變量(年齡和心境階段lt;緩解期為參照gt;)進行回歸分析。結果表明, 至少一個調節變量的回歸系數與0有顯著差異(見表2), 年齡的效應變得不顯著(β"= 0.015, p = 0.117), 緩解期患者與lt;輕gt;躁狂期患者的效應量差異依然顯著(β"= 0.397, p ="0.0007)。

3.3""子模型

盡管本研究發現患者在所有風險偏好測量類型上均比健康個體更偏好風險尋求, 但每種測量類型的效應量大小不同, 尤其是行為實驗任務和風險態度量表的差異顯著(β"= 0.371, p = 0.022)。因此, 本研究區分測量類型形成2個子模型再次檢驗, 包括行為實驗任務模型和日常態度和行為模型, 其中后者包括風險態度量表和日常風險行為的研究。本研究將這兩種類型進行合并的原因, 一是這2種測量主要以量表或問卷形式進行, 測量形式上較接近, 兩者效應量在本研究中也無顯著差異, 且以往研究表明這兩種測量類型的相關較高(Frey et al., 2017); 二是本研究中納入風險態度量表的文獻僅5篇, 將其單獨分為一個子模型, 可能會影響結論的穩健性。

3.3.1""行為實驗任務模型

首先, 三水平隨機模型比較雙相患者與健康個體在行為實驗任務中的風險偏好有無顯著差異。結果發現, 總體效應量顯著(k"= 88, Hedges' g"= 0.266, 95% CI [0.145, 0.387], t"= 4.36, p"lt; 0.001), 表明雙相患者(N"= 2161, Mage"= 36.33歲, 58.75%女性)比健康個體(N"= 2312; Mage"= 34.22歲, 53.84%女性)在行為實驗任務中也更偏好風險尋求。

其次, 對行為實驗任務測得的風險決策這一結果變量進行異質性檢驗。結果表明該模型同樣存在高異質性(QE"(87) = 284.79, p"lt; 0.001, I2"= 74.94%)。后續分析發現, 行為實驗任務模型的研究內方差(LRT = 8.82, p"= 0.003)和研究間方差(LRT = 6.45, p"= 0.011)顯著。在其總方差來源中, 抽樣方差、研究內方差和研究間方差分別為25.06%, 25.56%和49.38%。

然后, 本研究采用漏斗圖和Egger-MLMA回歸檢驗發表偏差。結果發現, 采用行為實驗任務的研究每個效應量在漏斗圖上基本均勻分布在總體效應量的兩側(見網絡版附圖2a), 且Egger-MLMA回歸結果也并不顯著(t"= 0.63, p"= 0.531), 表明該模型不存在顯著的發表偏差。

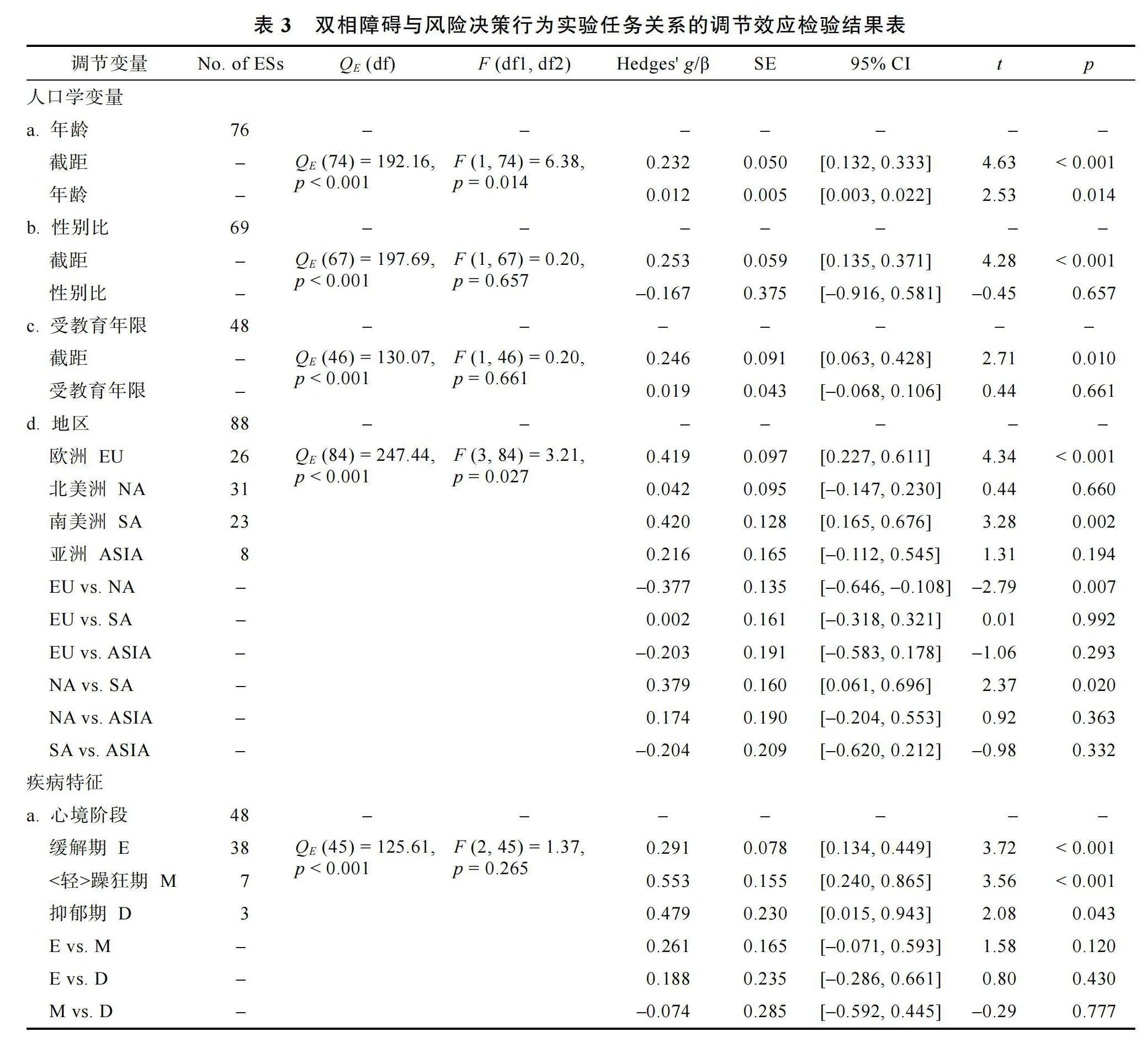

最后, 除了上文檢驗的任務類型和任務明確性, 本研究在行為實驗任務中再次檢驗樣本特征的調節作用(見表3)。結果發現, 年齡的調節作用顯著(β"= 0.012, p"= 0.014), 即隨著年齡增大, 雙相患者比健康個體在行為實驗任務中的風險尋求程度有所增加。地區的調節作用顯著, 歐洲(Hedges' g = 0.419, p lt; 0.001)和南美洲(Hedges' g = 0.420, p = 0.002)的效應量顯著, 且都顯著大于北美洲的效應量(歐洲: β"= 0.377, p = 0.007; 南美洲: β"= 0.379, p"= 0.020)。雖然未有其他樣本特征的顯著作用, 但不同心境階段的主效應均顯著, 即緩解期(Hedges' g = 0.291, p lt; 0.001)、lt;輕gt;躁狂期(Hedges' g"= 0.553, p lt; 0.001)和抑郁期患者(Hedges' g"= 0.479, p = 0.043)均比健康個體更偏好風險尋求。

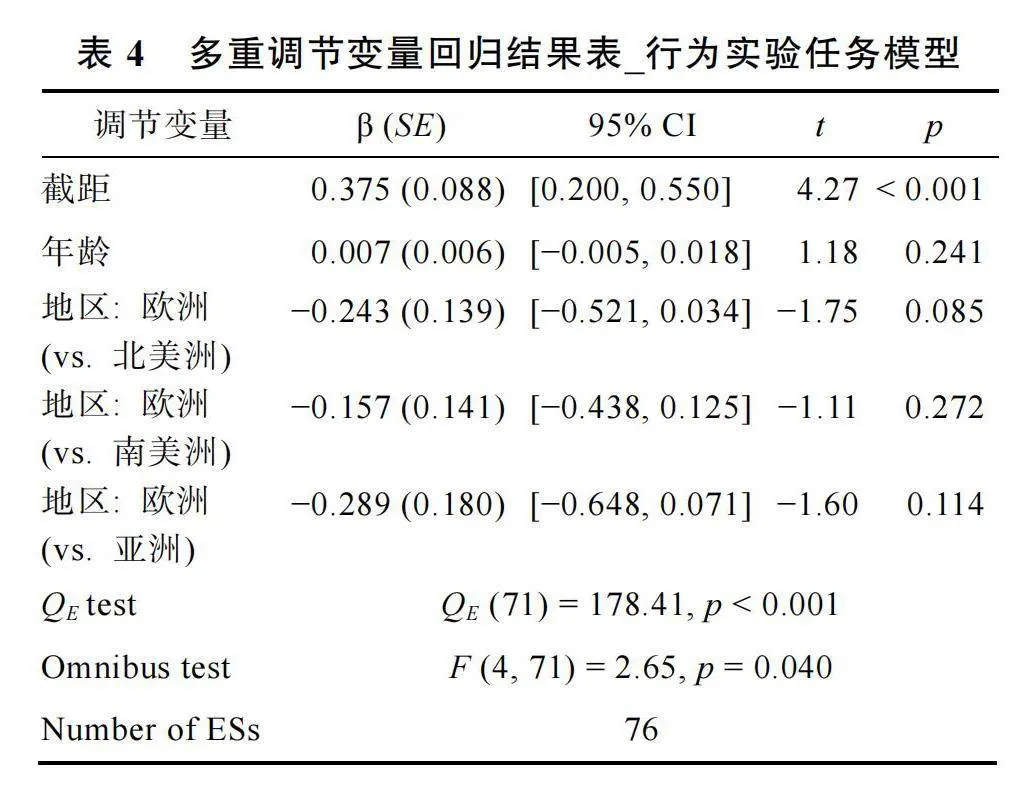

為了排除調節變量間的共線性, 根據Assink和Wibbelink (2016)的方法, 本研究納入所有顯著的調節變量(年齡和地區lt;歐洲為參照gt;)進行回歸分析。雖然Omnibus檢驗結果顯著, 但除了截距外并未有其他回歸系數顯著(見表4), 僅歐洲和北美洲的效應量有差異趨勢(β"= ?0.243, p = 0.085)。

3.3.2""日常風險態度和行為模型

首先, 三水平隨機模型比較雙相患者與健康個體在日常態度和行為中的風險偏好有無顯著差異。結果發現, 總體效應量同樣顯著(k"= 88, Hedges' g"= 0.360, 95% CI [0.232, 0.487], t"= 5.60, p"lt; 0.001), 表明雙相患者(N"= 2537, Mage"= 36.82歲, 62.41%女性)比健康個體(N"= 3815; Mage"= 36.39歲, 53.44%女性)在日常態度和行為中也同樣更偏好風險尋求。

其次, 對日常態度和行為測得的風險決策這一結果變量進行異質性檢驗。結果表明該模型同樣存在高異質性(QE"(87) = 378.16, p"lt; 0.001, I2"= 80.00%)。后續發現, 日常態度和行為模型的研究內方差(LRT = 57.32, p"lt; 0.001)和研究間方差(LRT = 6.77, p"= 0.009)顯著。在其總方差來源中, 抽樣方差、研究內方差和研究間方差分別為20.00%, 41.71 %和38.29%。

然后, 本研究采用漏斗圖和Egger-MLMA回歸檢驗發表偏差。結果發現, 采用日常態度和行為的研究每個效應量在漏斗圖上基本均勻分布在總體效應量的兩側(見網絡版附圖2b), 且Egger-MLMA回歸結果也不顯著(t"= 1.54, p"= 0.126), 表明該模型不存在顯著的發表偏差。

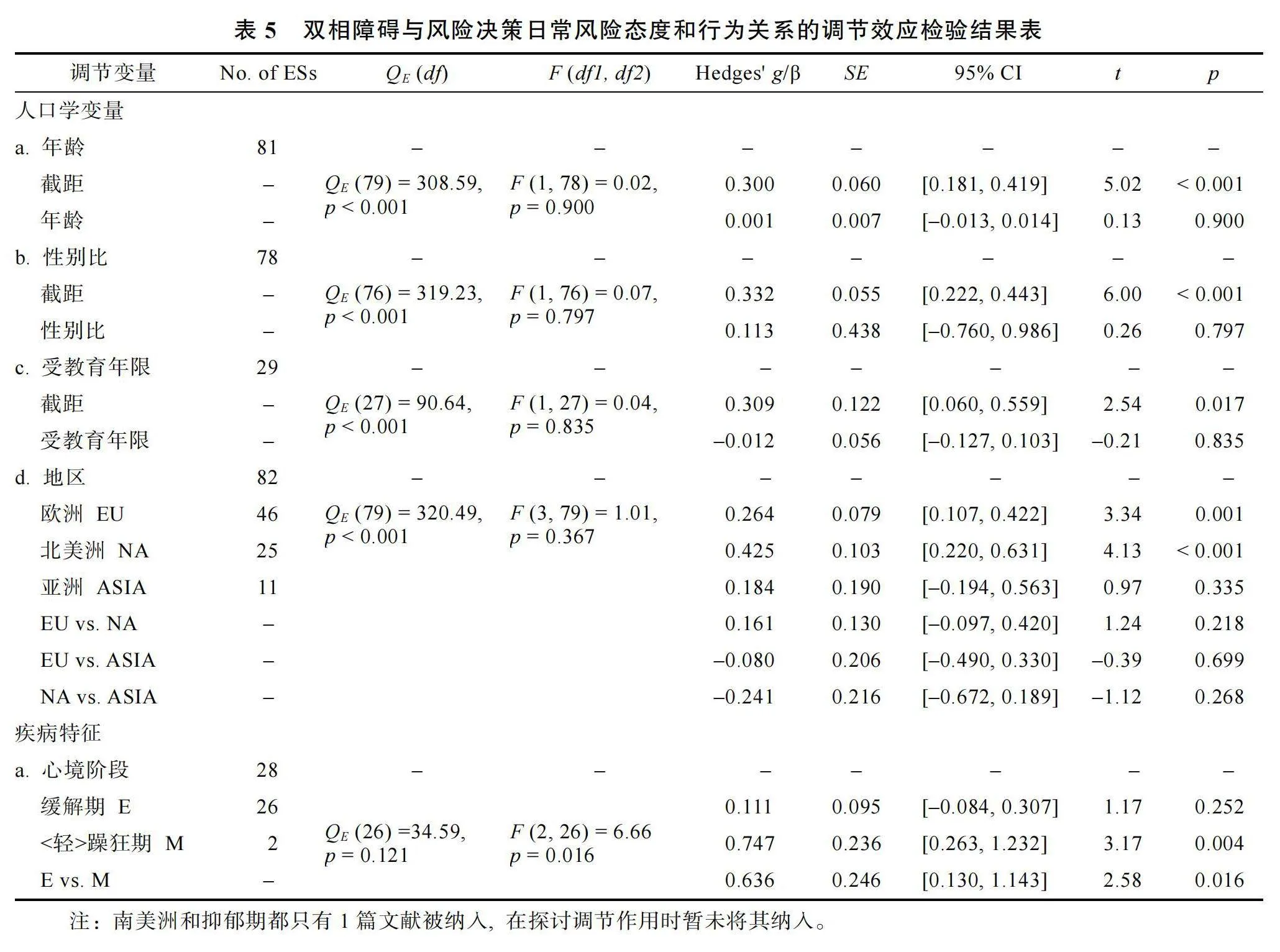

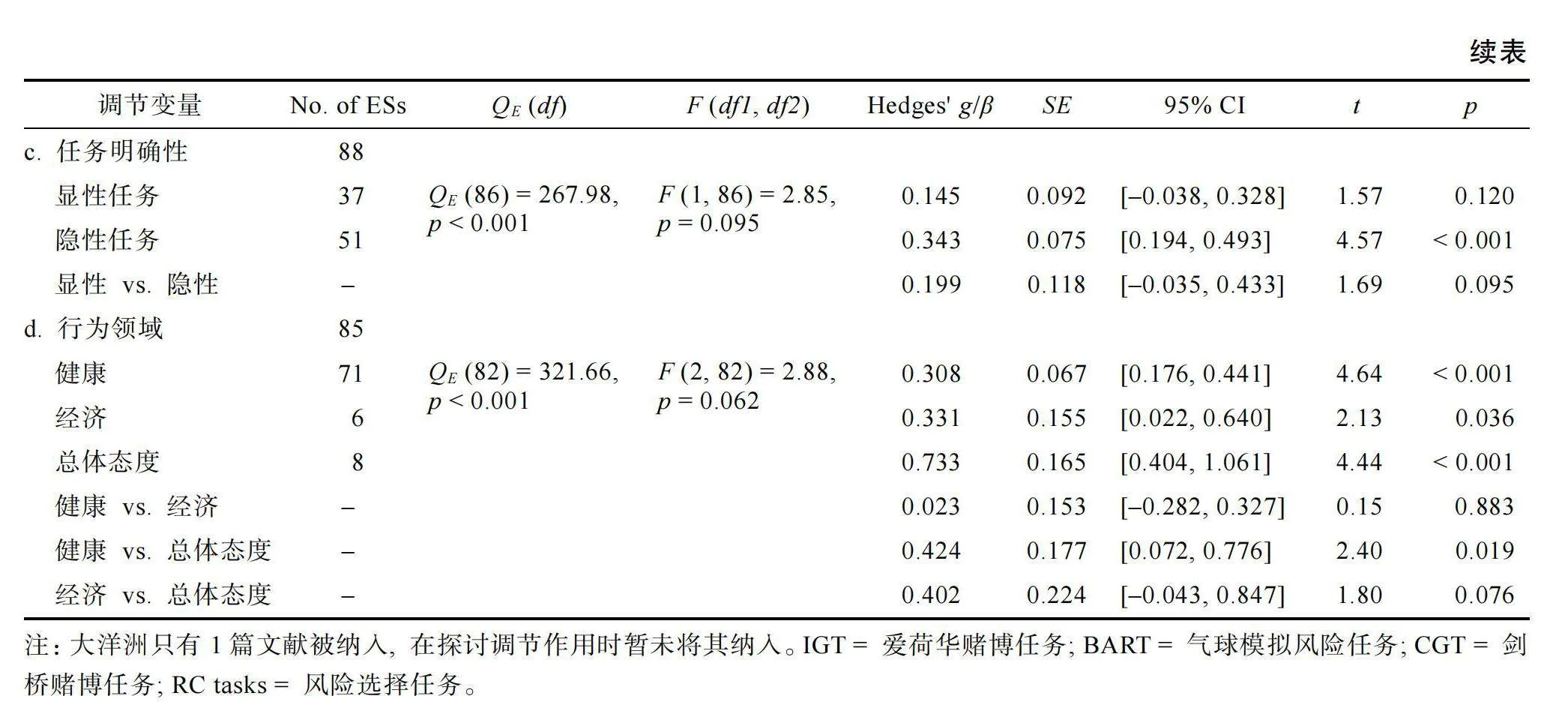

最后, 除了上文已檢驗的領域類型, 本研究在日常態度和行為中再次檢驗樣本特征的調節作用(見表5)。結果僅心境階段的調節作用顯著(p"= 0.016), lt;輕gt;躁狂期患者(Hedges' g = 0.747, p = 0.004)在日常態度和行為中比健康個體更偏好風險尋求, 且其效應量顯著大于緩解期患者(β"= 0.636,p = 0.016)。雖然其他樣本特征的作用不顯著, 但在地區中部分亞組的主效應顯著, 即以歐洲個體(Hedges' g = 0.264, p = 0.001)和北美洲個體(Hedges' g = 0.425, p lt; 0.001)為樣本的效應量顯著。由于日常態度和行為模型中僅心境階段的調節作用顯著, 繼而無需進行多調節變量回歸分析。

4 "討論

雙相患者在生活中確實容易做出許多風險行為, 如風險性行為、過度消費等(如Bodur et al., 2023; Di Nicola et al., 2010)。DSM-V也將“參與有災難性后果的高風險活動”納入lt;輕gt;躁狂期的診斷標準中。大量實證研究發現, 雙相障礙和風險決策有關(如Adida et al., 2008; Fletcher et al., 2013; Gu et al., 2020; Ramírez-Martín et al., 2024)。但因研究設計的不同(如, 采用不同風險偏好測量類型, 選取不同心境階段患者等), 研究結果有所差異。那么, 雙相障礙如何影響風險決策偏好(風險尋求還是風險規避)尚不明確。因此, 本研究采用三水平元分析, 囊括風險態度量表、行為實驗任務、日常風險行為等研究類型, 對雙相障礙與風險決策的關系進行系統梳理, 并發現一些有價值的結果。

4.1""雙相障礙與風險決策偏好的關系

研究發現, 雙相患者比健康個體更偏好風險尋求(Hedges' g"= 0.301), 該結果與Edge等人(2013)、Richard-Devantoy等人(2016)以及Ramírez-Martín等人(2020)中IGT任務的元分析結果一致, 也與大多實證研究結果相同(如Malloy-Diniz et al., 2011; Mason et al., 2014), 這回答了本研究第一個問題, 即“雙相患者與健康個體的風險偏好有無差異”。研究者基于模糊痕跡理論(Fuzzy-Trace Theory, FTT; Brainerd amp; Reyna, 1990)推測雙相患者風險尋求增加可能有2種途徑(Lukacs et al., 2021):一是患者在強烈情緒影響下可能改變其對信息的加工方式(Rivers et al., 2008), 變得不再像健康個體那樣傾向于要義加工(Gist processing), 而是過度依賴字面加工(Verbatim processing)。這可能使得他們對風險和價值的感知發生變化, 最終改變其風險偏好(Reyna et al., 2015); 二是患者依然依賴要義加工但可能賦予事件不恰當的要義, 潛在創造一個“預加載反應” (Pre-load response), 使其未來面對同一決策時再次做出不恰當反應(如, 躁狂期患者易賦予風險行為積極要義和“風險尋求”反應)。然而, 目前僅Sicilia等(2020)發現雙相患者的要義加工偏好下降, 但尚無研究直接驗證上述推論是否成立, 因此仍需未來進一步研究來檢驗。

4.2""雙相障礙與風險決策關系的調節因素

本研究考察了樣本特征和測量特征對雙相障礙與風險決策關系的調節作用, 嘗試回答了本研究第二個問題, 即潛在因素如何調節雙相障礙與風險決策偏好的關系。

4.2.1 "人口學特征的調節作用

本研究發現年齡的調節作用顯著, 即隨著年齡增長, 雙相患者與健康個體的風險尋求差異隨之增加。然而, 這一正向作用僅在行為實驗任務中顯著, 在日常態度和行為中不顯著。我們推測這可能與行為實驗任務除了反映風險偏好外還涉及認知能力有關。例如, IGT任務與個體的工作記憶、策略學習等認知能力有關(蔡厚德 等, 2012; 徐四華 等, 2013)。當個體隨年齡增長, 他們的認知能力往往緩慢下降(Hartshorne amp; Germine, 2015), 變得更難以正確感知風險和獎賞, 也更難以識別和優化決策策略, 因而呈現出風險尋求增加的趨勢。有研究表明, 雙相障礙會損傷雙相患者的認知能力(Sparding et"al., 2015), 甚至會加劇認知能力的衰退(Cullen et"al., 2016; da Silva et al., 2013; Diniz et al., 2017), 尤其是老年人群(John et al., 2019)。那么, 雙相患者與健康個體的認知能力差異便可能隨著年齡增大, 導致兩者在行為實驗任務中的風險偏好差異也隨之增大。

本研究在總體模型中并未發現地區的調節作用, 但無論地區如何, 患者都表現出比健康個體更高風險尋求的趨勢(歐洲: Hedges' g"= 0.333; 北美洲: Hedges' g"= 0.189; 南美洲: Hedges' g"= 0.415; 亞洲: Hedges' g"= 0.220, p"=.087)。然而, 細分測量類型后結果有所差異。在行為實驗任務中, 地區的調節作用顯著, 歐洲和南美洲的效應量顯著且顯著大于北美洲, 而北美洲和亞洲的效應量不顯著; 在日常態度和行為中, 地區的調節作用不顯著, 但歐美的效應量顯著而亞洲的效應量不顯著。對于亞洲研究, 或許因研究數量不足(48篇行為任務研究中7篇亞洲研究, 27篇日常態度和行為研究中2篇亞洲研究)削弱了統計檢驗力(42.70%和10.90%), 掩蓋了亞洲患者與亞洲健康個體的風險偏好差異。隨著未來亞洲研究的積累, 其統計檢驗力有望提升, 結果可能有所變化。對于北美洲在行為實驗任務研究中的效應量不顯著, 盡管其統計檢驗力也較低(8.18%), 但現有趨勢表明, 增加研究可能不足以改變結果, 因此我們推測這可能與行為實驗任務選用有關。不同地區選用任務類型不同(χ2(9, N"= 48) = 25.40, p"= 0.003)。相較歐洲研究多采用IGT和CGT任務、南美洲研究都采用IGT任務, 北美洲研究選用任務更平衡。加之, 不同任務的效應量不同。據此, 北美洲效應量不顯著或許與不同任務融合有關, 這表明未來需積累不同地區的研究并均衡選用任務, 才能更準確分析地區的作用。

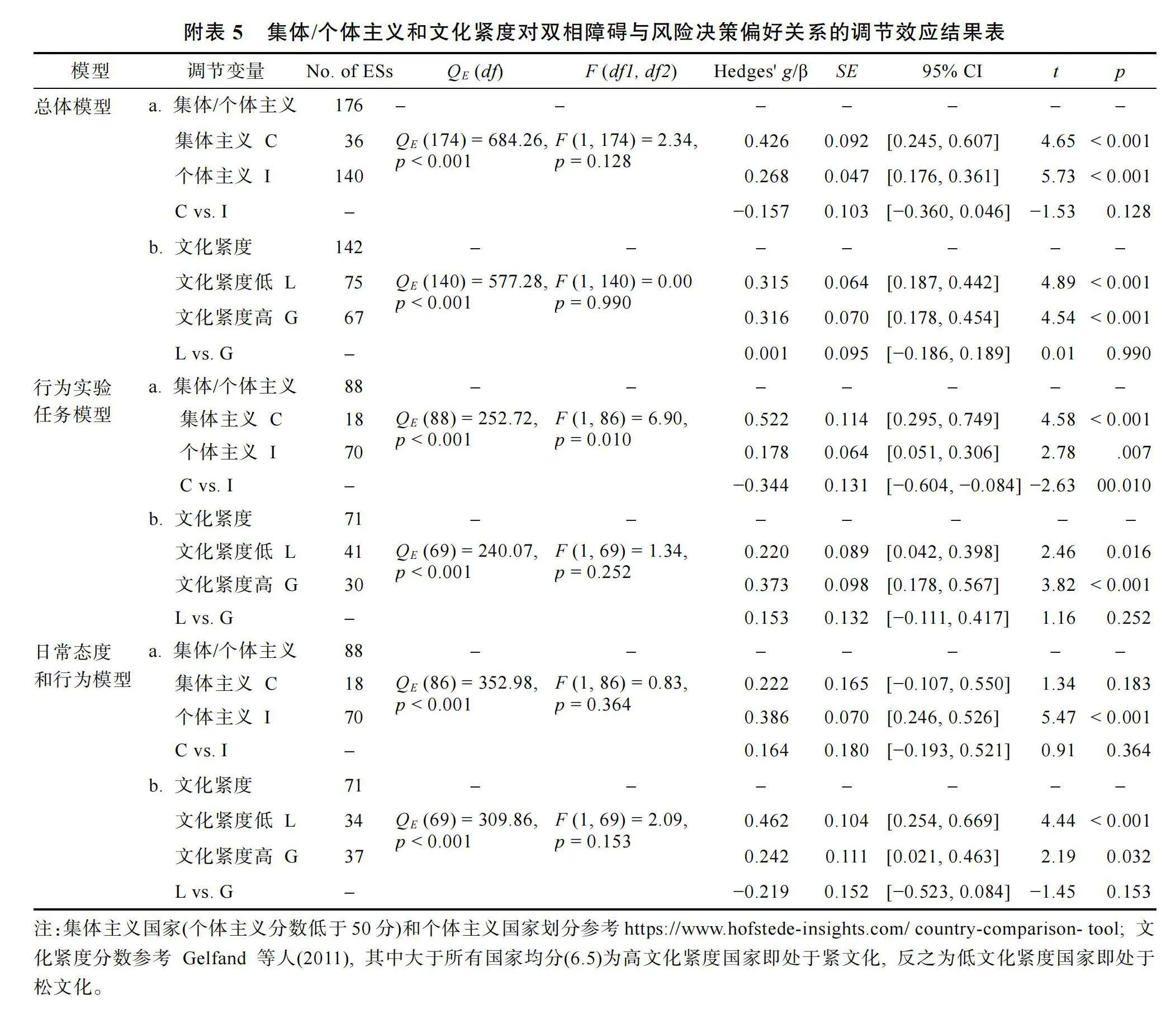

上述地區差異深層次上可能與文化差異有關。一方面, 當前研究主要涉及風險性行為、物質濫用等行為。基于文化松緊度(Gelfand et al., 2011), 相較歐美國家, 亞洲國家往往處于“緊”文化, 通常有較嚴格的社會規范, 對越軌行為的容忍度低、懲罰度高。因此歐美文化對風險性行為、物質濫用(尤其是大麻等毒品)等行為的接受度和常見度比亞洲文化更高(Arria et al., 2017; Bragazzi et al., 2021; Jia et al., 2018; Kandel et al., 1981)。即便是雙相患者也可能存在這一文化差異。我們嘗試根據文化緊度將研究所涉國家分為“高”和“低”2種類型, 然后比較2種文化下患者與健康個體的風險偏好差異是否不同。結果表明(見網絡版附表5), 不論處于“緊”文化還是“松”文化的患者均比健康個體更偏好風險尋求, 但我們發現在日常態度和行為測量中, “松”文化的效應量(Hedges' g"= 0.462)確實大于“緊”文化的效應量(Hedges' g"= 0.242), 這初步驗證了我們的推測, 但仍需更多研究檢驗。另一方面, 亞洲與歐美個體在風險偏好上可能存在固有差異。亞洲個體通常比歐美個體更偏好風險尋求(Chen et al., 2020; Du et al., 2002), 這可能與集體主義文化有關。因為集體主義文化能給個體提供強大的社會支持, 即使冒險失敗也可能因他人的幫助而得到“緩沖” (Hsee amp; Weber, 1999)。因此, 不同地區健康個體的基線差異可能導致亞洲患者與亞洲健康個體間的差異變得不明顯。我們將現有研究所涉國家分為“集體主義國家”和“個體主義國家”進行比較。結果發現(見網絡版附表5), 在日常態度和行為中, 僅個體主義國家的效應量顯著(Hedges' g"= 0.386), 這與前述研究結果相符。但在行為實驗任務中卻發現集體主義(Hedges' g"= 0.522)和個體主義國家(Hedges' g"= 0.178)的效應量均顯著, 且集體主義國家的效應量顯著更大, 這與前述研究結果不符, 值得未來進一步探索。總之, 未來需積累更多關于雙相患者風險決策的地區和文化差異的研究, 更深入探究文化差異與地區效應的關系。

4.2.2""心境階段的調節作用

本研究發現心境階段的調節作用顯著, 不論心境階段如何, 雙相患者均比健康個體更偏好風險尋求(緩解期: Hedges' g"= 0.245; lt;輕gt;躁狂期: Hedges' g"= 0.604; 抑郁期: Hedges' g"= 0.417)。區分測量類型后, 這一作用在日常態度和行為模型中顯著, 而在行為實驗模型中不顯著。然而, lt;輕gt;躁狂期患者與緩解期患者的風險偏好差異穩定存在, 這為雙相患者風險偏好變化與心境階段有關提供證據。

值得注意的是, 不論在總體模型、行為實驗任務模型還是日常態度和行為模型中, lt;輕gt;躁狂期患者均比健康個體更偏好風險尋求(總體模型: Hedges' g"= 0.604; 行為實驗任務: Hedges' g"= 0.553; 日常態度和行為: Hedges' g"= 0.747)。這一發現與躁狂/輕躁狂發作的診斷標準“過度地參與那些很可能產生痛苦后果的高風險活動”相符(APA, 2013)。研究表明, 行為趨近系統會調節個體對獎勵和目標的趨近行為, 往往與風險尋求有關(Braddock et al., 2011)。而lt;輕gt;躁狂期患者恰巧對這一系統異常敏感, 對趨近線索會有過度反應, 進而易表現出比健康個體更高的風險尋求程度(Katz et al., 2021)。

有趣的是, 緩解期患者雖然總體與健康個體有顯著差異, 但存在于行為實驗任務中(Hedges' g"= 0.291, p"lt; 0.001)而非日常態度和行為中(Hedges' g"= 0.111, p"= 0.252)。由此推測或許緩解期患者可能在生活中不再偏好風險尋求, 但其難以恢復原有水平的認知能力使其在依靠認知能力的行為實驗任務中依然有與常人的差異(Mann-Wrobel et al., 2011)。這一推測也間接證明了測量類型的差異可能引發結果偏差。應指出的是, 由于對發病期患者的研究難度大, 目前研究數量還較匱乏, 基于現有研究樣本得出心境階段調節作用的結論還需審慎, 未來需積累研究以檢驗風險偏好跨心境變化的結論。

4.2.3""測量特征的調節作用

本研究還考察了雙相障礙與風險決策偏好關系是否因測量特征不同而有所差異。首先確實發現不同風險偏好測量類型間的結果不同, 主要是風險態度量表和行為實驗任務間的結果有顯著差異。但穩定的是, 不論在哪種測量類型中, 雙相患者均比健康個體更偏好風險尋求(風險態度量表: Hedges' g"= 0.624; 行為實驗任務: Hedges' g"= 0.252; 日常風險行為: Hedges' g"= 0.312), 僅僅在程度上有所差異。這種程度差異或許不僅源于測量形式不同, 還和測量內容有關。風險態度量表將風險偏好定義為一般性風險態度或對特定領域的風險態度, 行為實驗任務將風險偏好抽象為選擇高風險高收益選項的傾向, 而日常風險行為則將風險偏好具象為具體風險行為的頻率。這些操作定義的差異及其具體選取的指標差異都可能使得個體對備擇選項或風險行為的感知發生變化(如, 風險大小、后果性質等), 最終影響其風險偏好。因此, 探索雙相患者在不同測量類型上表現出差異背后的原因, 即探究雙相患者風險尋求增加的潛在心理機制是未來研究的重要方向之一。

本研究在日常態度和行為上未發現領域類型的調節作用, 僅揭示總體態度(Hedges' g"= 0.733)、健康領域(Hedges' g"= 0.308)和經濟領域(Hedges' g"= 0.331)的主效應顯著。盡管這些效應量方向一致,"但大小差異明顯, 尤其是總體態度的效應遠大于其他兩者。這表明雙相患者可能在一般風險偏好上變化顯著, 但在特定領域內的變化程度各異。這與Frey等人(2017)提出的雙因子模型相符, 包括一般風險偏好的總因子和健康、經濟等7個不同方面的子因子。此外, 鑒于風險決策有領域特異性(岳靈紫 等, 2018), 雙相障礙對風險決策的影響可能會因領域而異。然而, 目前研究集中于健康和經濟領域, 因此, 未來需積累更多雙相患者在不同領域的風險決策研究進一步檢驗領域特異性的存在。

本研究在行為實驗任務上未發現任務類型的調節作用, 僅觀察到IGT和CGT任務效應量顯著。這可能是由于BART和RC任務的研究數量有限(48篇行為實驗任務研究中, 8篇采用BART任務, 7篇采用RC任務), 削弱了它們的統計檢驗力(BART: 27.80%; RC: 5.51%), 使得雙相患者與健康個體的差異難以被探測。隨著這些任務研究增加, 統計檢驗力有望提升, 研究結果可能隨之改變。因此, 未來需進一步積累相關行為實驗任務的研究, 以重新檢驗這一調節作用。

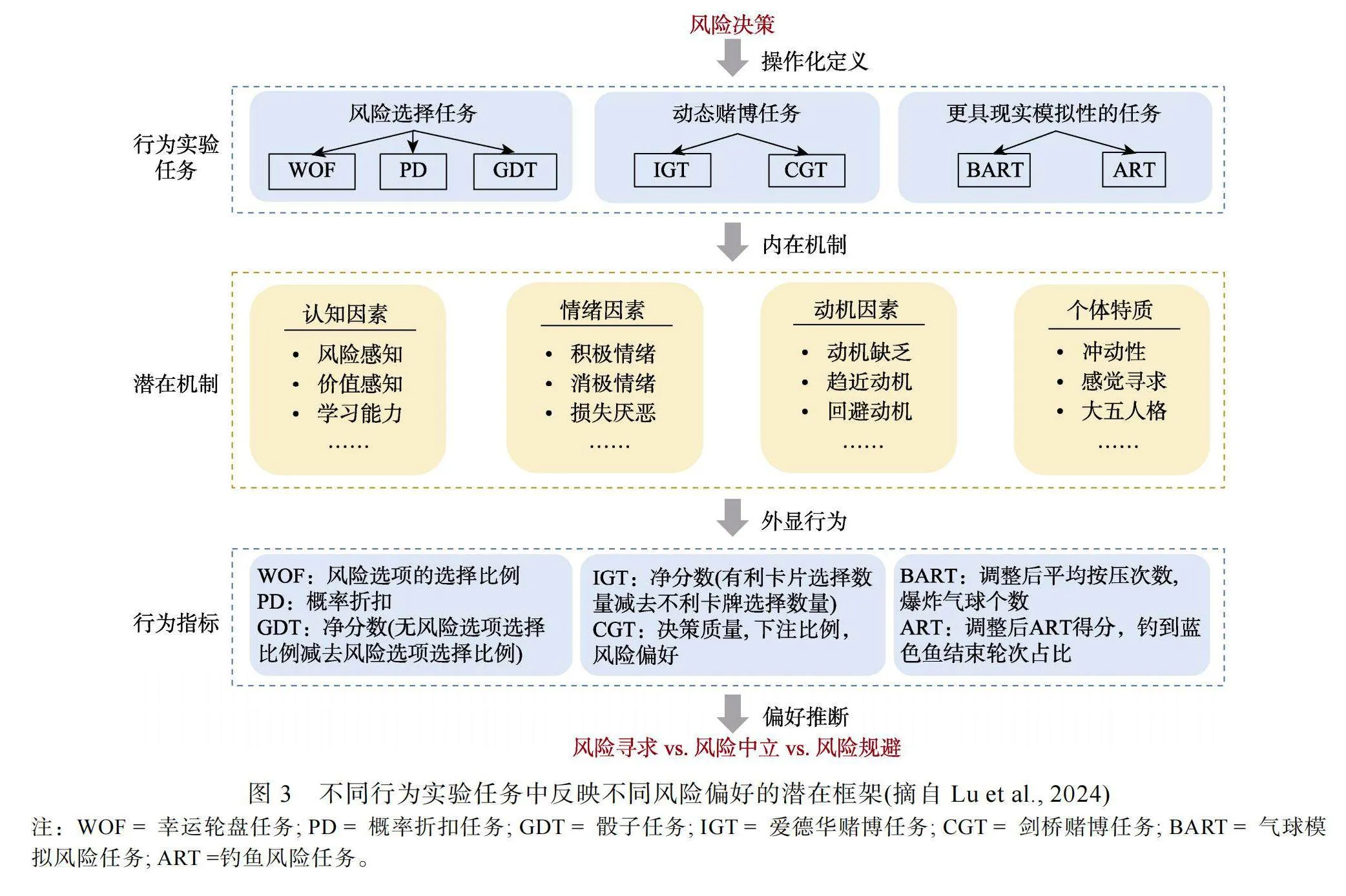

盡管本研究未直接揭示任務類型對結果的影響, 但基于對重性抑郁障礙患者風險決策的元分析, 我們對任務效應提出“操作化–機制–測量”特異性(Operationalization-Mechanism-Measure Specificity)的理論框架(見圖3, Lu et al., 2024)。在此框架下, 本研究結果可能受兩方面因素影響:首先是操作化特異性, 即不同行為實驗任務的操作化定義涉及到風險決策構念的不同成分, 其中的獨特成分可能導致任務間風險偏好的差異(Buelow amp; Blaine, 2015)。本研究中, IGT和CGT任務主效應顯著, 而BART和RC任務不顯著。這可能反映了這些任務涉及的風險決策構念成分有所區別, 也強調了任務選擇在全面評估雙相患者風險決策中的重要性。二是機制特異性, 即不同任務可能反映了雙相患者受損的不同心理機制。如, RC任務可能與風險感知和價值感知有關(Chan amp; Saqib, 2021; Hosker–Field et al., 2016; Kahneman amp; Tversky, 1979); 而IGT任務除了反映風險偏好, 還涉及工作記憶、抑制控制、策略學習等認知能力(蔡厚德 等, 2012)。因此, 本研究中IGT任務的效應量顯著大于RC任務, 可能預示著患者在與IGT相關的認知能力上受損, 而非風險感知和價值感知。此外, 即便任務間損傷機制相同也可能造成不同的外顯行為。如, IGT任務需要個體學會識別并更多選擇有利卡牌(最優策略), 若其無法識別可能更多選擇不利卡牌而表現出風險尋求(徐四華 等, 2013); BART任務的最優策略要求個體在權衡風險和收益的同時適當冒險, 否則會按壓次數較少即表現出風險規避(Lejuez et al., 2002)。那么, 若患者因病無法習得策略將在IGT和BART任務中表現出不同的外顯行為, 繼而被判定為不同的風險偏好。目前結果支持了IGT任務的推測但在BART任務中未發現顯著效應。因此, 未來研究不能只關注個體的外顯行為, 而要結合其背后的心理機制, 不斷積累有關雙相障礙影響風險決策心理機制的研究, 以厘清風險決策乃至行為實驗任務和雙相障礙受損機制間的關系。上述推測, 不僅值得雙相患者風險偏好研究的重視, 也是所有決策研究應注意的。它提醒我們僅憑單一行為任務的結果得出風險偏好的普遍性結論并不嚴謹, 而應該關注跨任務范式的一致性。這也是有必要采用元分析梳理以往研究結果的重要原因之一。未來需基于多種不同行為實驗任務乃至不同測量類型的結果綜合判斷雙相患者的風險偏好, 并挖掘這背后的心理機制。

4.3""不足與展望

本研究還存在以下幾點不足:(1)不同亞組的樣本分布不夠均衡, 本研究的部分結果可能會受一定影響。例如, 關于心境階段的調節作用, 大多以往研究并未區分患者所處的心境階段, 而區分的研究則多集中于緩解期患者, 躁狂和抑郁等發病期患者的研究相對匱乏。盡管這與研究難度有關, 但也不可避免地造成個別心境階段的主效應以及各心境階段間的效應量差異難以被探查。(2)本研究考察了人口學特征、心境階段和測量特征的調節作用, 但受文獻限制, 可能會忽略其他潛在的調節變量。例如, 服用藥物情況可能是潛在調節變量。有研究發現, 服用抗精神病藥物的雙相患者比未服用的患者認知能力更弱(Arts et al., 2011; Torrent et al., 2011), 進而其風險偏好可能不同(P?lsson et al., 2013)。(3)鑒于目前雙相障礙影響風險決策的研究側重于揭示現象, 鮮有探究現象背后的心理機制, 因此本元分析著重梳理了主效應而未能探究其心理機制。(4)本研究盡可能全面搜索和篩選了相關文獻, 但是一些數據不全的文獻較難被納入。

基于本研究發現, 我們認為未來研究可關注以下方面:

第一, 未來研究應關注雙相患者風險偏好的跨心境差異。以往研究多集中緩解期患者, 缺乏對發病期患者的研究, 尤其是抑郁期。更應指出的是, 部分研究直接將雙相患者與健康個體比較, 而忽略患者中混雜著不同心境, 這可能造成研究結果的偏差。如, 本研究發現lt;輕gt;躁狂期患者的風險尋求程度顯著大于緩解期患者, 但若將兩類患者混合與健康個體比較, 就無法明確各心境階段的主效應, 還會產生有偏結果。而且, 即便都是緩解期患者, 其前一個心境階段的不同(即抑郁期、lt;輕gt;躁狂期或緩解期)也可能影響當下的風險偏好。因此, 未來研究應盡可能區分患者的心境階段, 尤其應重視對發病期患者的研究, 以進一步探索雙相障礙和風險決策的跨心境差異。

第二, 未來應重視跨測量類型的研究和一致性分析。本研究雖然在不同風險偏好測量類型中都得到雙相患者更偏好風險尋求的結論, 但是行為實驗任務與風險態度量表的效應量差異顯著, 而且不同行為實驗任務下也有所差異。據此, 未來探究雙相患者乃至健康個體的風險偏好時, 應重視跨任務范式和跨測量類型的差異。行為實驗任務范式因能將風險決策抽象化, 并可動態測量個體風險偏好, 成為當下風險決策研究的主流方式。但是, 一些相對復雜的行為實驗任務也易引入其他干擾因素。如, IGT任務中表現出的風險偏好可能涉及記憶和策略學習能力, 而BART任務中表現出的風險偏好可能涉及動機水平, 因此兩者雖都自稱是對風險偏好的測量, 但測得的心理本質并不完全相同, 都難以完全刻畫個體的風險偏好, 與真實生活中的風險行為也有所出入。這啟示了未來研究應采用多樣化的測量類型, 并重視考察跨測量類型的一致性, 以得出關于雙相障礙與風險決策關系更純粹的結論, 這也有利于對潛在的心理機制挖掘。除了關注測量類型的多樣性, 未來研究還要注重測量內容的廣泛性。目前多數行為實驗任務聚焦于經濟領域的賭博任務, 而對安全、社交等決策領域的風險態度和行為鮮有關注。即便在真實風險行為的測量中, 也主要局限于健康領域的抽煙、喝酒等, 以及經濟領域的賭博和消費行為等。這一局限使得現有數據難以全面揭示雙相患者真實的風險決策狀況。因此, 未來采用多樣化測量類型時應拓展測量內容的范圍, 延伸至更多決策領域。

第三, 未來研究應重視多地域樣本的均衡和比較。目前雙相障礙和風險決策研究多集中于歐美樣本, 而雙相患者的風險決策也可能存在一定地域和文化差異。如, 本研究發現歐美患者均比健康個體更偏好風險尋求, 但亞洲患者的風險偏好與健康個體卻并無差異。我們還發現, 在行為實驗任務的選擇上, 歐洲國家多選擇IGT和CGT任務, 南美洲國家全部選擇IGT任務, 北美洲國家選擇任務較平衡, 而亞洲國家則多選擇IGT和BART任務。因此, 未來研究一方面需多積累亞洲、非洲等地區的樣本, 同時也需要考慮測量類型上的多樣性和均衡性。

第四, 未來研究應重視探究雙相障礙影響風險決策的心理機制。目前雙相障礙與風險決策間關系的研究多停留在現象揭示, 直接探究現象背后心理機制的研究相對匱乏。有研究者基于FTT理論提出, 雙相患者在強烈情緒狀態下既可能過度依賴字面加工, 改變其風險感知或價值感知, 進而影響其風險偏好; 也可能賦予事件不恰當要義, 使其未來面對同一決策時仍做出不恰當行為(Lukacs et al., 2021)。也有研究者認為, lt;輕gt;躁狂期患者因對行為趨近系統超敏繼而比健康個體更偏好風險尋求(Katz et al., 2021)。還有研究者從動機強度(Hershenberg et al., 2016)、損失厭惡(Lasagna et al., 2022)等角度提出原因推測。但目前只有一些間接證據(如Collett, 2016; Sicilia et al., 2020)支持上述推測。因此, 未來研究有必要檢驗這些推測以揭示雙相障礙影響風險決策的心理機制。這不僅有助于描繪患者風險決策的心理過程, 還能為干預其風險決策提供理論依據和實踐指導。

最后, 未來應重視縱向追蹤研究, 以彌補當前雙相障礙與風險決策關系研究中依賴橫斷研究在因果推斷上的局限。橫斷研究雖能揭示雙相患者與健康個體在風險偏好上的差異, 但受限于個體間差異, 當樣本量較小時尤其如此。而縱向追蹤研究不僅能消除部分個體間差異的影響, 追蹤患者風險決策隨時間的變化, 構建患者風險決策的動態發展模型, 還能從被試內角度比較同一患者隨心境階段轉換的風險偏好變化, 更深入地理解心境階段的作用。因此, 未來研究應重視對雙相患者隊列的長期隨訪。

5 "結論

本研究采用三水平元分析的方法, 系統梳理以往雙相障礙和風險決策研究, 得出以下主要結論:

(1)相較于健康個體, 雙相患者總體上更偏好風險尋求。

(2)在樣本特征上, 年齡(總體及行為實驗任務模型)、地區(行為實驗任務模型)和心境階段(總體及日常態度和行為模型)起調節作用。具體而言, 雙相患者隨年齡增長與健康個體的風險尋求差異也隨之增加; 歐洲和南美洲患者在行為實驗任務中的效應量顯著且顯著大于北美洲患者; 所有心境階段患者均比健康個體更偏好風險尋求, 其中lt;輕gt;躁狂期患者的效應最為穩定, 且顯著大于緩解期患者。

(3)在測量特征上, 無論采用何種風險偏好測量類型, 雙相患者均比健康個體更偏好風險尋求。特別是風險態度量表與行為實驗任務中的差異顯著。在行為實驗任務中, 雙相患者在IGT和CGT任務中比健康個體更偏好風險尋求, 且IGT任務效應量顯著大于RC任務; 而在日常態度和行為中, 患者在健康、經濟領域及總體態度上均比健康個體更偏好風險尋求, 且總體態度的效應量顯著大于健康領域。

參""考""文""獻

*標記為納入元分析的文獻

*Adida, M., Clark, L., Pomietto, P., Kaladjian, A., Besnier, N., Azorin, J. M., Jeanningros, R., amp; Goodwin, G. M. (2008). Lack of insight may predict impaired decision making in manic patients. Bipolar Disorders, 10(7), 829?837. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-5618.2008.00618.x

*Adida, M., Jollant, F., Clark, L., Besnier, N., Guillaume, S., Kaladjian, A., ... Courtet, P. (2011). Trait-related decision-making impairment in the three phases of bipolar disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 70(4), 357–365. https://doi."org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.01.018

American Psychiatric Association. (2013)."Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders"(5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. https://doi.org/10."1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Amlung, M., Marsden, E., Holshausen, K., Morris, V., Patel, H., Vedelago, L., ... McCabe, R. E. (2019). Delay discounting as a transdiagnostic process in psychiatric disorders: A meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 76(11), 1176–1186. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.2102

*Anderson, Z., Fairley, K., Villanueva, C. M., Carter, R. M., amp; Gruber, J. (2021). No group differences in traditional economics measures of loss aversion and framing effects in bipolar i disorder. Plos One, 16(11), e0258360. https://"doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258360

Arria, A. M., Caldeira, K. M., Allen, H. K., Bugbee, B. A., Vincent, K. B., amp; O'Grady, K. E. (2017). Prevalence and incidence of drug use among college students: An 8-year longitudinal analysis. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 43(6), 711?718. https://doi.org/10.1080/"00952990.2017.1310219

Arts, B., Jabben, N. E. J. G., Krabbendam, L., amp; van Os, J. (2011). A 2-year naturalistic study on cognitive functioning in bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 123(3), 190?205. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01601.x

Assink, M., amp; Wibbelink, C. J. M. (2016). Fitting three-level meta-analytic models in R: A step-by-step tutorial. The Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 12(3), 154–174. https://doi.org/10.20982/tqmp.12.3.p154

*Ayidaga, T., Ozel-Kizil, E.T., ?olak, B., amp; Akman-Ayidaga, E. (2022). Detailed analysis of risk-taking in association with impulsivity and aggression in euthymic patients with bipolar disorder type I. Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 34(7), 917?929. https://doi.org/10.1080/20445911.2022."2098303

Azorin, J. M., Belzeaux, R., Kaladjian, A., Adida, M., Hantouche, E., Lancrenon, S., amp; Fakra, E. (2013). Risks associated with gender differences in bipolar I disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 151(3), 1033–1040. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.08.031

*Bauer, I. E., Diniz, B. S., Meyer, T. D., Teixeira, A. L., Sanches, M., Spiker, D., Zunta-Soares, G., amp; Soares, J. C. (2018). Increased reward-oriented impulsivity in older bipolar patients: A preliminary study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 225, 585–592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017."08.067

*Bauer, I. E., Meyer, T. D., Sanches, M., Spiker, D., Zunta-Soares, G., amp; Soares, J. C. (2017). Are self-rated and behavioural measures of impulsivity in bipolar disorder mainly related to comorbid substance use problems? Cognitive Neuropsychiatry, 22(4), 298–314. https://doi.org/"10.1080/13546805.2017.1324951

Benazzi, F. (2003). The role of gender in depressive mixed state. Psychopathology, 36(4), 213–217. https://doi.org/"10.1159/000072792

Birmaher, B. (2013). Bipolar disorder in children and adolescents. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 18(3), 140–148. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12021

Blais, A. -R., amp; Weber, E. U. (2006). A Domain-Specific Risk-Taking (DOSPERT) scale for adult populations. Judgment and Decision Making, 1(1), 33–47. https://doi."org/10.1017/s1930297500000334

Blankenstein, N. E., Peper, J. S., Crone, E. A., amp; van Duijvenvoorde, A. C. K. (2017). Neural mechanisms underlying risk and ambiguity attitudes. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 29(11), 1845–1859. https://doi."org/10.1162/jocn_a_01162

*Bodur, B., Do?anav?argil Baysal, G. ?., amp; Erdo?an, A. (2023). Comparison of behavioral addictions between euthymic bipolar disorder patients and healthy volunteers. Neuropsychiatric Investigation, 6(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/"10.5152/NeuropsychiatricInvest.2023.22028

Bolton, S., Warner, J., Harriss, E., Geddes, J., amp; Saunders, K. E. A. (2021). Bipolar disorder: Trimodal age-at-onset distribution. Bipolar Disorders, 23(4), 341–356. https://doi."org/10.1111/bdi.13016

Bora, E., Yucel, M., amp; Pantelis, C. (2009). Cognitive endophenotypes of bipolar disorder: A meta-analysis of neuropsychological deficits in euthymic patients and their first-degree relatives. Journal of Affective Disorders, 113(1-2), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.009

Braddock, K. H., Dillard, J. P., Voigt, D. C., Stephenson, M. T., Sopory, P., amp; Anderson, J. W. (2011). Impulsivity partially mediates the relationship between BIS/BAS and risky health behaviors. Journal of Personality, 79(4), 793–810. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2011.00699.x

Bragazzi, N. L., Beamish, D., Kong, J. D., amp; Wu, J. (2021). Illicit drug use in Canada and implications for suicidal behaviors, and household food insecurity: Findings from a large, nationally representative survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(12), 6425. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126425

Brainerd, C. J., amp; Reyna, V. F. (1990). Gist is the grist: Fuzzy-trace theory and the new intuitionism. Developmental Review, 10(1), 3–47. https://doi.org/10."1016/0273–2297(90)90003–M

*Brambilla, P., Perlini, C., Bellani, M., Tomelleri, L., Ferro, A., Cerruti, S., ... Frangou, S. (2013). Increased salience of gains versus decreased associative learning differentiate bipolar disorder from schizophrenia during incentive decision making. Psychological Medicine, 43(3), 571–580. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291712001304

Brener, N. D., Kann, L., Kinchen, S. A., Grunbaum, J. A., Whalen, L., Eaton, D., Hawkins, J., amp; Ross, J. G. (2004). Methodology of the youth risk behavior surveillance system. MMWR. Recommendations and reports: Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Recommendations and Reports, 53(RR-12), 1–13.

Buelow, M. T., amp; Blaine, A. L. (2015). The assessment of risky decision making: A factor analysis of performance on the Iowa Gambling Task, Balloon Analogue Risk Task, and Columbia Card Task. Psychological Assessment, 27(3), 777?785. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038622

Butler, S., Rosman, A., Seleski, S., Garcia, M., Lee, S., Barnes, J., amp; Schwartz, A. (2012). A medical risk attitude subscale for DOSPERT. Judgment and Decision Making, 7(2), 189?195. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1930297500003028

Byrnes, J. P., Miller, D. C., amp; Schafer, W. D. (1999). Gender differences in risk taking: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 125(3), 367–383. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033–"2909.125.3.367

Cai, H. D., Zhang, Q., Cai, Q., amp; Chen, Q. R. (2012). Iowa Game Task and cognitive neural mechanisms on decision-making. Advances in Psychological Science, 20(9), 1401?1410. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1042.2012.0140

[蔡厚德, 張權, 蔡琦, 陳慶榮. (2012). 愛荷華博弈任務(IGT)與決策的認知神經機制. 心理科學進展, 20(9), 1401?1410. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1042.2012.0140]

*Caletti, E., Paoli, R. A., Fiorentini, A., Cigliobianco, M., Zugno, E., Serati, M., ... Altamura, A. C. (2013). Neuropsychology, social cognition and global functioning among bipolar, schizophrenic patients and healthy controls: Preliminary data. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, 661. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2013.00661

Chan, E. Y., amp; Saqib, N. U. (2021). The moderating role of processing style in risk perceptions and risky decision making. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 34(2), 290–299. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.2210

Charness, G., amp; Gneezy, U. (2012). Strong evidence for gender differences in risk taking. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 83(1), 50–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/"j.jebo.2011.06.007

Chen, X. J., Ba, L., amp; Kwak, Y. (2020). Neurocognitive underpinnings of cross-cultural differences in risky decision"making. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 15(6),"671–680. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsaa078

Cheung, M. W. L. (2014). Modeling dependent effect sizes with three-level meta-analyses: A structural equation modeling approach. Psychological Methods, 19(2), 211–229. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032968

*Clark, L., Iversen, S. D., amp; Goodwin, G. M. (2001). A neuropsychological investigation of prefrontal cortex involvement in acute mania. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158(10), 1605?1611. https://doi.org/10.1176/"appi.ajp.158.10.1605

Collett, J. (2016). It's not all about that bas: Trait bipolar disorder vulnerability weakly correlated with trait bas and not predictive of risky decision–making"[Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Swinburne University of Technology.

Croson, R., amp; Gneezy, U. (2009). Gender differences in preferences. Journal of Economic Literature, 47(2), 448–"474. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.47.2.448

Cullen, B., Ward, J., Graham, N. A., Deary, I. J., Pell, J. P., Smith, D. J., amp; Evans, J. J. (2016). Prevalence and correlates of cognitive impairment in euthymic adults with bipolar disorder: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 205, 165?181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad."2016.06.063

da Silva, J., Gon?alves-Pereira, M., Xavier, M., amp; Mukaetova-Ladinska, E. B. (2013). Affective disorders and risk of developing dementia: Systematic review. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 202(3), 177?186. https://doi.org/10."1192/bjp.bp.111.101931

Defoe, I. N., Dubas, J. S., Figner, B., amp; van Aken, M. A. (2015). A meta–analysis on age differences in risky decision making: Adolescents versus children and adults. Psychological Bulletin, 141(1), 48–84. https://doi.org/10."1037/a0038088

Dekkers, T. J., Popma, A., van Rentergem, J. A. A., Bexkens, A., amp; Huizenga, H. M. (2016). Risky decision making in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A meta-regression"analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 45, 1–16. https://"doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.03.001

*de Moraes, P. H. P., Neves, F. S., Vasconcelos, A. G., Lima, I. M. M., Brancaglion, M., Sedyiama, C. Y., ..."Malloy-Diniz, L. F. (2013). Relationship between neuropsychological and clinical aspects and suicide attempts in euthymic bipolar patients. Psicologia: Reflexao e Critica, 26(1), 160–167. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-79722013000100017

*Dickerson, F., Schroeder, J., Katsafanas, E., Khushalani, S., Origoni, A. E., Savage, C., ... Yolken, R. H. (2018). Cigarette smoking by patients with serious mental illness, 1999-2016: An increasing disparity. Psychiatric Services, 69(2), 147–153. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201700118

*Dickerson, F., Stallings, C. R., Origoni, A. E., Vaughan, C., Khushalani, S., Schroeder, J., amp; Yolken, R. H. (2013). Cigarette smoking among persons with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder in routine clinical settings, 1999-2011. Psychiatric Services, 64(1), 44–50. https://doi.org/10.1176/"appi.ps.201200143

*Di Nicola, M., Tedeschi, D., Mazza, M., Martinotti, G., Harnic, D., Catalano, V., ... Janiri, L. (2010). Behavioural addictions in bipolar disorder patients: Role of impulsivity and personality dimensions. Journal of Affective Disorders, 125(1-3), 82–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2009.12.016

Diniz, B. S., Teixeira, A. L., Cao, F., Gildengers, A., Soares, J. C., Butters, M. A., amp; Reynolds III, C. F. (2017). History of bipolar disorder and the risk of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 25(4), 357?362. https://doi.org/10."1016/j.jagp.2016.11.014

Dir, A. L., Coskunpinar, A., amp; Cyders, M. A. (2014). A meta-analytic review of the relationship between adolescent risky sexual behavior and impulsivity across gender, age, and race. Clinical Psychology Review, 34(7), 551–562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2014.08.004

Du, W., Green, L., amp; Myerson, J. (2002). Cross-cultural comparisons of discounting delayed and probabilistic rewards. Psychological Record, 52(4), 479–492. https://doi."org/10.1007/BF03395199

Duffy, A. (2009). The early course of bipolar disorder in youth at familial risk. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 18(3), 200–205.

Duval, S., amp; Tweedie, R. (2000). Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics, 56(2), 455–"463. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00455.x

*Edge, M. D., Johnson, S. L., Ng, T., amp; Carver, C. S. (2013). Iowa gambling task performance in euthymic bipolar I disorder: A meta-analysis and empirical study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 150(1), 115–122. https://doi.org/10."1016/j.jad.2012.11.027

*Ernst, M., Dickstein, D. P., Munson, S., Eshel, N., Pradella, A., Jazbec, S., Pine, D. S., amp; Leibenluft, E. (2004). Reward-related processes in pediatric bipolar disorder: A pilot study."Journal of Affective Disorders, 82, S89?S101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2004.05.022

Fernandes, A. C., amp; Garcia-Marques, T. (2020). A meta-"analytical review of the familiarity temporal effect: Testing assumptions of the attentional and the fluency-attributional accounts. Psychological Bulletin, 146(3), 187–217. https://"doi.org/10.1037/bul0000222

Fischhoff, B., amp; Broomell, S. B. (2020). Judgment and decision making. Annual Review of Psychology, 71(1), 331?355. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010419-"050747

*Fletcher, K., Parker, G. B., amp; Manicavasagar, V. (2013). Coping profiles in bipolar disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 54(8), 1177?1184. https://doi.org/10.1016/"j.comppsych.2013.05.011

*Frangou, S., Kington, J., Raymont, V., amp; Shergill, S. S. (2008). Examining ventral and dorsal prefrontal function in bipolar disorder: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study."European Psychiatry, 23(4), 300?308. https://doi."org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2007.05.002

Frey, R., Pedroni, A., Mata, R., Rieskamp, J., amp; Hertwig, R. (2017). Risk preference shares the psychometric structure of major psychological traits. Science Advances, 3(10), e1701381. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1701381

Gao, S., Assink, M., Cipriani, A., amp; Lin, K. (2017). Associations between rejection sensitivity and mental health outcomes: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 57, 59–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/"j.cpr.2017.08.007

Gelfand, M. J., Raver, J. L., Nishii, L., Leslie, L. M., Lun, J., Lim, B. C., … Yamaguchi, S. (2011). Differences between tight and loose cultures: A 33-nation study. Science, 332(6033), 1100–1104. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1197754

*Goldberg, J. F., Wenze, S. J., Welker, T. M., Steer, R. A., amp; Beck, A. T. (2005). Content‐specificity of dysfunctional cognitions for patients with bipolar mania versus unipolar depression: A preliminary study. Bipolar Disorders, 7(1), 49?56. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-5618.2004.00165.x

*Gomide Vasconcelos, A., Sergeant, J., Corrêa, H., Mattos, P., amp; Malloy-Diniz, L. (2014). When self-report diverges from performance: The usage of BIS-11 along with neuropsychological tests. Psychiatry Research, 218(1–2), 236–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2014.03.002

*Gu, Y. T., Zhou, C., Yang, J., Zhang, Q., Zhu, G. H., Sun, L., Ge, M. H., amp; Wang, Y. Y. (2020). A transdiagnostic comparison of affective decision‐making in patients with schizophrenia, major depressive disorder, or bipolar disorder. PsyCh Journal, 9(2), 199?209. https://doi.org/10."1002/pchj.351

*Haatveit, B., Westlye, L. T., Vaskinn, A., Flaaten, C. B., Mohn, C., Bjella, T., ... Ueland, T. (2023). Intra- and inter-individual cognitive variability in schizophrenia and bipolar spectrum disorder: An investigation across multiple cognitive domains."Schizophrenia, 9(1), 89. https://doi.org/"10.1038/s41537-023-00414-4

*Hariri, A. G., Karadag, F., Gokalp, P., amp; Essizoglu, A. (2011). Risky sexual behavior among patients in Turkey with bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and heroin addiction. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 8(8), 2284?2291. https://doi."org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02282.x

*Hart, K. L., Brown, H. E., Roffman, J. L., amp; Perlis, R. H. (2019). Risk tolerance measured by probability discounting among individuals with primary mood and psychotic disorders. Neuropsychology, 33(3), 417–424. https://doi."org/10.1037/neu0000506

Hartshorne, J. K., amp; Germine, L. T. (2015). When does cognitive functioning peak? The asynchronous rise and fall of different cognitive abilities across the life span. Psychological Science, 26(4), 433–443. https://doi.org/10."1177/0956797614567339

Hershenberg, R., Satterthwaite, T. D., Daldal, A., Katchmar, N., Moore, T. M., Kable, J. W., amp; Wolf, D. H. (2016). Diminished effort on a progressive ratio task in both unipolar and bipolar depression."Journal of Affective Disorders, 196, 97–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016."02.003

Hertwig, R., Barron, G., Weber, E. U., amp; Erev, I. (2004). Decisions from experience and the effect of rare events in risky choice. Psychological Science, 15(8), 534–539. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00715.x

*H?d?ro?lu, C., Esen, ?. D., Tunca, Z., Yal?ìn, ?. N. G., Lombardo, L., Glahn, D. C., amp; ?zerdem, A. (2013). Can risk-taking be an endophenotype for bipolar disorder? A study on patients with bipolar disorder type I and their first-degree relatives. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 19(4), 474?482. https://doi."org/10.1017/S1355617713000015

*Holmes, M. K., Bearden, C. E., Barguil, M., Fonseca, M., Monkul, E. S., Nery, F. G., … Glahn, D. C. (2009). Conceptualizing impulsivity and risk taking in bipolar disorder: Importance of history of alcohol abuse. Bipolar Disorders, 11(1), 33–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-5618."2008.00657.x

Hosker–Field, A. M., Molnar, D. S., amp; Book, A. S. (2016). Psychopathy and risk taking: Examining the role of risk perception. Personality and Individual Differences, 91, 123–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.11.059

Hox, J. J., Moerbeek, M., amp; van de Schoot, R. (2010). Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications."Routledge.

Hsee, C., amp; Weber, E. U. (1999). Cross-national differences in risk preference and lay predictions. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 12(2), 165–179. https://doi.org/10.1002/"(SICI)1099-0771(199906)12:2lt;165::AID-BDM316gt;3.0.CO;2-N

Huang, Y., Wang, Y., Wang, H., Liu, Z., Yu, X., Yan, J., … Wu, Y. (2019). Prevalence of mental disorders in China: A cross-sectional epidemiological study. The Lancet Psychiatry,"6(3), 211–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30511-X

*Ibanez, A., Cetkovich, M., Petroni, A., Urquina, H., Baez, S., Gonzalez-Gadea, M. L., ... Manes, F. (2012). The neural basis of decision-making and reward processing in adults with euthymic bipolar disorder or attention-deficit/"hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). PloS One, 7(5), e37306. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0037306

Isen, A. M., amp; Patrick, R. (1983). The effect of positive feelings on risk taking: When the chips are down. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 31(2), 194–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/0030–5073(83)90120–4

Ji, C. Y. (2007). Adolescent health risk behavior. Chinese Journal of School Health, 28(4), 289–291.

[季成葉. (2007). 青少年健康危險行為. 中國學校衛生, 28(4), 289–291.]

*Ji, S., Ma, H., Yao, M., Guo, M., Li, S., Chen, N., ... Hu, B. (2021). Aberrant temporal variability in brain regions during risk decision making in patients with bipolar I disorder: A dynamic effective connectivity study. Neuroscience, 469, 68?78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j."neuroscience.2021.06.024

Jia, Z., Jin, Y., Zhang, L., Wang, Z., amp; Lu, Z. (2018). Prevalence of drug use among students in mainland China: A systematic review and meta-analysis for 2003-2013. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 186, 201–206. https://doi."org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.12.047

*Jogia, J., Dima, D., Kumari, V., amp; Frangou, S. (2012). Frontopolar cortical inefficiency may underpin reward and working memory dysfunction in bipolar disorder. The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry, 13(8), 605?615. https://doi.org/10.3109/15622975.2011.585662

John, A., Patel, U., Rusted, J., Richards, M., amp; Gaysina, D. (2019). Affective problems and decline in cognitive state in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 49(3), 353–365. https://doi.org/10."1017/S0033291718001137

Johnson, E. J., amp; Tversky, A. (1983). Affect, generalization, and the perception of risk. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45(1), 20–31. https://doi.org/10.1037/"0022–3514.45.1.20

Josef, A. K., Richter, D., Samanez-Larkin, G. R., Wagner, G. G., Hertwig, R., amp; Mata, R. (2016). Stability and change in risk-taking propensity across the adult life span. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 111(3), 430–450. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000090

Kahneman, D., amp; Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–292. https://doi.org/10.2307/1914185

Kandel, D. B., Adler, I., amp; Sudit, M. (1981). The epidemiology of adolescent drug use in France and Israel. American Journal of Public Health, 71(3), 256–265. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.71.3.256

Kathawalla, U., amp; Syed, M. (2021). Discrimination, life stress, and mental health among Muslims: A preregistered systematic review and meta-analysis. Collabra: Psychology, 7(1), 28248. https://doi.org/10.1525/collabra.28248

Katz, B. A., Naftalovich, H., Matanky, K., amp; Yovel, I. (2021). The dual-system theory of bipolar spectrum disorders: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 83, 101945. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101945

Kepes, S., amp; Thomas, M. A. (2018). Assessing the robustness of meta-analytic results in information systems: Publication bias and outliers. European Journal of Information Systems, 27(1), 90?123. https://doi.org/10.1080/0960085X.2017."1390188

*Kollmann, B., Scholz, V., Linke, J., Kirsch, P., amp; Wessa, M. (2017). Reward anticipation revisited- evidence from an fMRI study in euthymic bipolar I patients and healthy first-degree relatives. Journal of Affective Disorders, 219, 178–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.04.044

*Kollmann, B., Yuen, K., Scholz, V., amp; Wessa, M. (2019). Cognitive variability in bipolar I disorder: A cluster-"analytic approach informed by resting-state data. Neuropharmacology, 156, 107585. https://doi.org/10.1016/"j.neuropharm.2019.03.028

Krantz, M., Goldstein, T., Rooks, B., Merranko, J., Liao, F., Gill, M. K., ... Birmaher, B. (2018). Sexual risk behavior among youth with bipolar disorder: Identifying demographic and clinical risk factors. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 57(2), 118–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2017.11.015

*Lamy, M. (2009)."Neural correlates of impulsivity and risk taking in bipolar disorder"[Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Cincinnati.

Lapomarda, G., Pappaianni, E., Siugzdaite, R., Sanfey, A. G., Rumiati, R. I., amp; Grecucci, A. (2021). Out of control: An altered parieto-occipital-cerebellar network for impulsivity in bipolar disorder. Behavioural Brain Research, 406, 113228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2021.113228

Lasagna, C. A., Pleskac, T. J., Burton, C. Z., McInnis, M. G., Taylor, S. F., amp; Tso, I. F. (2022). Mathematical modeling of risk-taking in bipolar disorder: Evidence of reduced behavioral consistency, with altered loss aversion specific to those with history of substance use disorder. Computational Psychiatry, 6(1), 96–116. https://doi.org/10."5334/cpsy.61

*Le, V., Kirsch, D. E., Tretyak, V., Weber, W., Strakowski, S. M., amp; Lippard, E. T. C. (2021). Recent perceived stress, amygdala reactivity to acute psychosocial stress, and alcohol and cannabis use in adolescents and young adults with bipolar disorder. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 767309. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.767309

Lejuez, C. W., Read, J. P., Kahler, C. W., Richards, J. B., Ramsey, S. E., Stuart, G. L., Strong, D. R., amp; Brown, R. A. (2002). Evaluation of a behavioral measure of risk taking: The Balloon Analogue Risk Task (BART). Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 8(2), 75–84. https://doi."org/10.1037//1076-898x.8.2.75

*Levy, B. (2013). Autonomic nervous system arousal and cognitive functioning in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders, 15(1), 70–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/bdi.12028

Lewandowski, K. E., Sperry, S. H., Malloy, M. C., amp; Forester, B. P. (2014). Age as a predictor of cognitive decline in bipolar disorder. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 22(12), 1462–1468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j."jagp.2013.10.002

*Linke, J., King, A. V., Poupon, C., Hennerici, M. G., Gass, A., amp; Wessa, M. (2013). Impaired anatomical connectivity and related executive functions: Differentiating vulnerability and disease marker in bipolar disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 74(12), 908–916. https://doi.org/10.1016/j."biopsych.2013.04.010

*Lippard, E. T. C., Kirsch, D. E., Kosted, R., Le, V., Almeida, J. R. C., Fromme, K., amp; Strakowski, S. M. (2023). Subjective response to alcohol in young adults with bipolar disorder and recent alcohol use: A within-subject randomized placebo-controlled alcohol administration study. Psychopharmacology, 240(4), 739–753. https://doi.org/10."1007/s00213-023-06315-9

Lu, J., Zhao, X., Wei, X., amp; He, G. (2024). Risky decision-"making in major depressive disorder: A three-level meta-"analysis. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 24(1), 100417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijchp."2023.100417

Lukacs, J. N., Sicilia, A. C., Jones, S., amp; Algorta, G. P. (2021). Interactions and implications of Fuzzy-trace theory for risk taking behaviors in bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 293, 305–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021."06.035

Lüdecke, D. (2019). ESC: Effect size computation for meta analysis"(Version 0.5.1). https://CRAN.R-project.org/"package=esc.

*Malloy-Diniz, L. F., Neves, F. S., Abrantes, S. S. C., Fuentes, D., amp; Corrêa, H. (2009). Suicide behavior and neuropsychological assessment of type I bipolar patients. Journal of Affective Disorders, 112(1-3), 231?236."https://"doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2008.03.019

*Malloy-Diniz, L. F., Neves, F. S., de Moraes, P. H. P., De Marco, L. A., Romano-Silva, M. A., Krebs, M. O., amp; Corrêa, H. (2011). The 5-HTTLPR polymorphism, impulsivity and suicide behavior in euthymic bipolar patients. Journal of Affective Disorders, 133(1-2), 221?226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2011.03.051

Mann-Wrobel, M. C., Carreno, J. T., amp; Dickinson, D. (2011). Meta-analysis of neuropsychological functioning in euthymic bipolar disorder: An update and investigation of moderator variables. Bipolar Disorders, 13(4), 334–342. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-5618.2011.00935.x

*Marengo, E., Martino, D. J., Igoa, A., Fassi, G., Scápola, M., Baamonde, M. U., amp; Strejilevich, S. A. (2015). Sexual risk behaviors among women with bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Research, 230(3), 835?838."https://doi.org/10.1016/j."psychres.2015.10.021

*Martin, K., Woo, J., Timmins, V., Collins, J., Islam, A., Newton, D., amp; Goldstein, B. I. (2016). Binge eating and emotional eating behaviors among adolescents and young adults with bipolar disorder."Journal of Affective Disorders, 195, 88–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.02.030

*Martino, D. J., amp; Strejilevich, S. A. (2014). A comparison of decision making in patients with bipolar i disorder and schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research, 156(1), 135?136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2014.03.019

*Martino, D. J., Strejilevich, S. A., Torralva, T., amp; Manes, F. (2011). Decision making in euthymic bipolar I and bipolar II disorders. Psychological Medicine, 41(6), 1319–1327. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291710001832

*Martyn, F. M., McPhilemy, G., Nabulsi, L., Quirke, J., Hallahan, B., McDonald, C., amp; Cannon, D. M. (2023). Alcohol use is associated with affective and interoceptive network alterations in bipolar disorder. Brain and Behavior, 13(1), e2832. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.2832

*Mason, L., O'Sullivan, N., Montaldi, D., Bentall, R. P., amp; El-Deredy, W. (2014). Decision-making and trait impulsivity in bipolar disorder are associated with reduced prefrontal regulation of striatal reward valuation. Brain, 137(8), 2346?2355. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awu152

Meertens, R. M., amp; Lion, R. (2008). Measuring an individual's tendency to take risks: The risk propensity scale. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 38(6), 1506–1520. https://doi."org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2008.00357.x

Mellers, B., Schwartz, A., amp; Ritov, I. (1999). Emotion-based choice. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 128(3), 332–345. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.128.3."332

Merikangas, K. R., Jin, R., He, J. P., Kessler, R. C., Lee, S., Sampson, N. A., ... Zarkov, Z. (2011). Prevalence and correlates of bipolar spectrum disorder in the world mental health survey initiative. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68(3), 241–251. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry."2011.12

Miklowitz, D. J., amp; Johnson, S. L. (2006). The psychopathology and treatment of bipolar disorder. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 2, 199–235. https://doi.org/"10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095332

Miller, J. N., amp; Black, D. W. (2020). Bipolar disorder and suicide: A review. Current Psychiatry Reports, 22(2), 6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-020-1130-0

*Murphy, F. C., Rubinsztein, J. S., Michael, A., Rogers, R. D., Robbins, T. W., Paykel, E. S., amp; Sahakian, B. J. (2001). Decision-making cognition in mania and depression. Psychological Medicine, 31(4), 679?693."https://doi.org/"10.1017/s0033291701003804

*Naiberg, M. R., Newton, D. F., Collins, J. E., Bowie, C. R., amp; Goldstein, B. I. (2016). Impulsivity is associated with blood pressure and waist circumference among adolescents with bipolar disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 83, 230–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.08.019

National Institutes of Health. (2014). Study quality assessment tools."Retrieved from: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-"topics/study-quality-assessment-tools

*Obeid, S., Chok, A., Sacre, H., Haddad, C., Tahan, F., Ghanem, L., Azar, J., amp; Hallit, S. (2021). Are eating disorders associated with bipolar disorder type I? Results of a Lebanese case-control study. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 57(1), 326–334. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12567

*Ono, Y., Kikuchi, M., Hirosawa, T., Hino, S., Nagasawa, T., Hashimoto, T., Munesue, T., amp; Minabe, Y. (2015). Reduced prefrontal activation during performance of the Iowa Gambling Task in patients with bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, 233(1), 1?8. https://doi.org/10."1016/j.pscychresns.2015.04.003

P?lsson, E., Figueras, C., Johansson, A. G., Ekman, C. J., Hultman, B., ?stlind, J., amp; Landén, M. (2013). Neurocognitive function in bipolar disorder: A comparison between bipolar I and II disorder and matched controls. BMC Psychiatry, 13(1), 1?9."https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-"244X-13-165

Paluckait?, U., amp; ?ardeckait?-Matulaitien?, K. (2017). Adolescents' perception of risky behaviour on the Internet. In Z. Bekirogullari, M. Y. Minas, amp; R. X. Thambusamy (Eds.), Health and Health Psychology - icHamp;Hpsy 2017, Vol 30. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences"(pp. 284–292). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10."15405/epsbs.2017.09.27

*Pavlickova, H., Turnbull, O., amp; Bentall, R. P. (2014). Cognitive vulnerability to bipolar disorder in offspring of parents with bipolar disorder. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 53(4), 386–401. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc."12051

Plana-Ripoll, O., Weye, N., Knudsen, A. K., Hakulinen, C., Madsen, K. B., Christensen, M. K., ... McGrath, J. J. (2023). The association between mental disorders and subsequent years of working life: A Danish population-based cohort study. The Lancet Psychiatry, 10(1), 30–39. https://doi.org/"10.1016/S2215-0366(22)00376-5

Plans, L., Barrot, C., Nieto, E., Rios, J., Schulze, T. G., Papiol, S., ... Benabarre, A. (2019). Association between completed suicide and bipolar disorder: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Affective Disorders, 242, 111–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.08.054

Pleskac, T. J. (2008). Decision making and learning while taking sequential risks. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 34(1), 167–185. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.34.1.167

*Powers, R. L., Russo, M., Mahon, K., Brand, J., Braga, R. J., Malhotra, A. K., amp; Burdick, K. E. (2013). Impulsivity in bipolar disorder: Relationships with neurocognitive dysfunction and substance use history. Bipolar Disorders, 15(8), 876?884. https://doi.org/10.1111/bdi.12124

Prietzel, T. T. (2020). The effect of emotion on risky decision making in the context of prospect theory: A comprehensive literature review. Management Review Quarterly, 70, 313–353. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301–019–00169–2

Rai, S., Mishra, B. R., Sarkar, S., Praharaj, S. K., Das, S., Maiti, R., Agrawal, N., amp; Nizami, S. H. (2018). Higher impulsivity and HIV-risk taking behaviour in males with alcohol dependence compared to bipolar mania: A pilot study. Community Mental Health Journal, 54(2), 218–223. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-017-0139-2

Ramírez-Martín, A., Ramos-Martín, J., Mayoral-Cleries, F., Moreno-Küstner, B., amp; Guzman-Parra, J. (2020). Impulsivity, decision-making and risk-taking behaviour in bipolar disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 50(13), 2141–2153. https://doi."org/10.1017/S0033291720003086

*Ramírez-Martín, A., Sirignano, L., Streit, F., Foo, J. C., Forstner, A. J., Frank, J., ... Guzmán-Parra, J. (2024). Impulsivity, decision-making, and risk behavior in bipolar disorder and major depression from bipolar multiplex families. Brain and Behavior, 14(2), e3337. https://doi.org/"10.1002/brb3.3337

*Reddy, L. F., Lee, J., Davis, M. C., Altshuler, L., Glahn, D. C., Miklowitz, D. J., amp; Green, M. F. (2014). Impulsivity and risk taking in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology, 39(2), 456–463. https://doi.org/"10.1038/npp.2013.218

Reyna, V. F., Weldon, R. B., amp; McCormick, M. (2015). Educating intuition: Reducing risky decisions using Fuzzy-"trace theory. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 24(5), 392–398. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721415588081

*Richard-Devantoy, S., Olié, E., Guillaume, S., amp; Courtet, P. (2016). Decision-making in unipolar or bipolar suicide attempters. Journal of Affective Disorders, 190, 128–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.10.001

Richards, J. B., Zhang, L., Mitchell, S. H., amp; de Wit, H. (1999). Delay or probability discounting in a model of impulsive behavior: Effect of alcohol. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 71(2), 121–143. https://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.1999.71-121

Rivers, S. E., Reyna, V. F., amp; Mills, B. (2008). Risk taking under the influence: A Fuzzy-trace theory of emotion in adolescence. Developmental Review, 28(1), 107–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2007.11.002

Roberts, D. K., Alderson, R. M., Betancourt, J. L., amp; Bullard, C. C. (2021). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and risk-taking: A three-level meta-analytic review of behavioral, self-report, and virtual reality metrics. Clinical Psychology Review, 87, 102039. https://doi.org/10.1016/"j.cpr.2021.102039

Rodgers, M. A., amp; Pustejovsky, J. E. (2020). Evaluating meta-analytic methods to detect selective reporting in the presence of dependent effect sizes. Psychological Methods, 26(2), 141?160. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000300

*Rubinsztein, J. S., Michael, A., Underwood, B. R., Tempest, M., amp; Sahakian, B. J. (2006). Impaired cognition and decision-making in bipolar depression but no 'affective bias' evident. Psychological Medicine, 36(5), 629?639. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291705006689

*Salarvan, S., Sparding, T., Clements, C., Rydén, E., amp; Landén, M. (2019). Neuropsychological profiles of adult bipolar disorder patients with and without comorbid attention-"deficit hyperactivity disorder. International Journal of Bipolar Disorders, 7(1), 1?8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40345-"019-0149-9

*Saunders, K. E., Goodwin, G. M., amp; Rogers, R. D. (2016). Insensitivity to the magnitude of potential gains or losses when making risky choices: Women with borderline personality disorder compared with bipolar disorder and controls. Journal of Personality Disorders, 30(4), 530?544."https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi_2015_29_216

*Saxena, K., Simonetti, A., Verrico, C. D., Janiri, D., Nicola, M. D., Catinari, A., ... Soares, J. C. (2023). Neurocognitive correlates of cerebellar volumetric alterations in youth with pediatric bipolar spectrum disorders and bipolar offspring. Current Neuropharmacology, 21(6), 1367–1378. https://doi."org/10.2174/1570159X21666221014120332

Schaffer, A., Isomets?, E. T., Tondo, L., Moreno, D. H., Turecki, G., Reis, C., ... Yatham, L. N. (2015). International society for bipolar disorders task force on suicide: Meta-analyses and meta-regression of correlates of suicide attempts and suicide deaths in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders, 17(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/bdi.12271

*Scholz, V., Houenou, J., Kollmann, B., Duclap, D., Poupon, C., amp; Wessa, M. (2016). Dysfunctional decision-making related to white matter alterations in bipolar i disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 194, 72–79. https://doi.org/"10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.019

Sicilia, A. C., Lukacs, J. N., Jones, S., amp; Perez Algorta, G. (2020). Decision-making and risk in bipolar disorder: A quantitative study using fuzzy trace theory. Psychology and Psychotherapy, 93(1), 105–121. https://doi.org/10.1111/"papt.12215

*Simonetti, A., Kurian, S., Saxena, J., Verrico, C. D., Soares, J. C., Sani, G., amp; Saxena, K. (2021). Cognitive correlates of impulsive aggression in youth with pediatric bipolar disorder and bipolar offspring. Journal of Affective Disorders,"287, 387–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.03.044

Sparding, T., Silander, K., P?lsson, E., ?stlind, J., Sellgren, C., Ekman, C. J., ... Landén, M. (2015). Cognitive functioning in clinically stable patients with bipolar disorder I and II. PloS One, 10(1), e0115562. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal."pone.0115562

*Taylor Tavares, J. V., Clark, L., Cannon, D. M., Erickson, K., Drevets, W. C., amp; Sahakian, B. J. (2007). Distinct profiles of neurocognitive function in unmedicated unipolar depression and bipolar II depression. Biological Psychiatry, 62(8), 917–924. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.05."034

*Thomas, J., Knowles, R., Tai, S., amp; Bentall, R. P. (2007). Response styles to depressed mood in bipolar affective disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 100(1–3), 249–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2006.10.017

Tinner, L., Caldwell, D., Hickman, M., MacArthur, G. J., Gottfredson, D., Lana Perez, A., ... Campbell, R. (2018). Examining subgroup effects by socioeconomic status of public health interventions targeting multiple risk behaviour in adolescence. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 1180. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6042-0

Torrent, C., Martinez-Arán, A., Daban, C., Amann, B., Balanzá-Martínez, V., del Mar Bonnín, C., ... Vieta, E. (2011). Effects of atypical antipsychotics on neurocognition"in euthymic bipolar patients. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 52(6), 613?622."https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2010."12.009

*Uro?evi?, S., Youngstrom, E. A., Collins, P., Jensen, J. B., amp; Luciana, M. (2016). Associations of age with reward delay discounting and response inhibition in adolescents with bipolar disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders, 190, 649?656."https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.11.005

*Vancampfort, D., Hagemann, N., Wyckaert, S., Rosenbaum, S., Stubbs, B., Firth, J., ... Sienaert, P. (2017). Higher cardio-respiratory fitness is associated with increased mental and physical quality of life in people with bipolar disorder: A controlled pilot study."Psychiatry Research, 256, 219–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.06.066

*Vancampfort, D., Sienaert, P., Wyckaert, S., De Hert, M., Stubbs, B., Soundy, A., De Smet, J., amp; Probst, M. (2015). Health-related physical fitness in patients with bipolar disorder vs. healthy controls: An exploratory study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 177, 22–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/"j.jad.2014.12.058

*van Enkhuizen, J., Henry, B. L., Minassian, A., Perry, W., Milienne-Petiot, M., Higa, K. K., Geyer, M. A., amp; Young, J. W. (2014). Reduced dopamine transporter functioning induces high-reward risk-preference consistent with bipolar disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology, 39(13), 3112–3122. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2014.170

Viechtbauer, W. (2010). Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. Journal of Statistical Software, 36(3), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v036.i03

Wang, X. T., Zheng, R., Xuan, Y. H., Chen, J., amp; Li, S. (2016). Not all risks are created equal: A twin study and meta-analyses of risk taking across seven domains. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 145(11), 1548–1560. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000225

*Wei, G. X., Kan, B., Wu, J., amp; Wang, K. (2018). Decision-"making behavior in manic and euthymic bipolar disorder under uncertain risk conditions. Journal of Chifeng University (Natural Science Edition), 34(8), 97–101. https://doi.org/10.13398/j.cnki.issn1673-260x.2018.08.035

[魏格欣, 闞博, 吳娟, 汪凱. (2018). 躁狂期和緩解期雙相情感障礙患者在風險不明確情境下決策行為的研究與探討. 赤峰學院學報(自然科學版), 34(8), 97–101. https://doi.org/10.13398/j.cnki.issn1673-260x.2018.08.035]

*Williams, S. C., Davey-Rothwell, M. A., Tobin, K. E., amp; Latkin, C. (2017). People who inject drugs and have mood disorders—A brief assessment of health risk behaviors. Substance Use and Misuse, 52(9), 1181–1190. https://"doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2017.1302954

*Wong, S. C. Y., Ng, M. C. M., Chan, J. K. N., Luk, M. S. K., Lui, S. S. Y., Chen, E. Y. H., amp; Chang, W. C. (2021). Altered risk-taking behavior in early-stage bipolar disorder with a history of psychosis. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.763545

World Health Organization (WHO). (2022). Mental disorders."Retrieved Feb 12, 2023, from https://vizhub.healthdata."org/gbd-compare/

Xu, S. H., Fang, Z., amp; Rao, H. Y. (2013). Real or hypothetical monetary rewards modulates risk taking behavior. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 45(8), 874?886. https://doi.org/10."3724/SP.J.1041.2013.00874

[徐四華, 方卓, 饒恒毅. (2013). 真實和虛擬金錢獎賞影響風險決策行為. 心理學報, 45(8), 874?886. https://doi."org/10.3724/SP.J.1041.2013.00874]

*Yechiam, E., Hayden, E. P., Bodkins, M., O'Donnell, B. F., amp; Hetrick, W. P. (2008). Decision making in bipolar disorder: A cognitive modeling approach. Psychiatry Research, 161(2), 142–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2007."07.001

Yue, L. Z., Li, S., amp; Liang, Z. Y. (2018). New avenues for the development of domain-specific nature of risky decision making. Advances in Psychological Science, 26(5), 928?"938. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1042.2018.00928

[岳靈紫, 李紓, 梁竹苑. (2018). 風險決策中的領域特異性. 心理科學進展, 26(5), 928?938. https://doi.org/10.3724/"SP.J.1042.2018.00928]

*Zeng, B. E. (2019). The relationship between college students'"suicide behavior and risk decision-making"[Unpublished master's thesis]. Southern Medical University, Guangzhou.

[曾寶爾. (2019). 大學生自殺行為與風險決策的關系研究"(碩士學位論文). 南方醫科大學, 廣州.]

Zhang, D. C., Highhouse, S., amp; Nye, C. D. (2019). Development and validation of the general risk propensity scale (GRiPS). Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 32(2), 152–167. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.2102

Zhu. C. G. (2020). Analysis of the investment risk preference of bipolar disorder-mania patients in remission and healthy first-degree relatives (siblings) [Unpublished master's thesis]. Anhui Medical University, China.

[朱承剛. (2020). 緩解期雙相躁狂患者及其健康一級親屬(同胞)投資風險偏好的研究 (碩士學位論文). 安徽醫科大學.]

*Zhu, Q., Liang, W. J., Zhang, G. C., Wu, X. H., amp; Guan, N. H. (2019). Social cognition and its impact on social functioning in patients with euthymic bipolar disorder. Guangdong Medical Journal, 40(18), 2671?2677. https://"doi.org/10.13820/j.cnki.gdyx.20190901

[朱麒, 梁文靖, 張桂燦, 吳秀華, 關念紅. (2019). 緩解期雙相障礙患者社會認知及對社會功能的影響. 廣東醫學, 40(18), 2671?2677. https://doi.org/10.13820/j.cnki.gdyx."20190901]

Risky decision-making in bipolar disorder: Evidence from a three-level meta-analysis

LU Jiaqi1,2, LI Yusi1, HE Guibing1

(1"Department of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310058,"China)(2"Jing Hengyi School of Education, Hangzhou Normal University, Hangzhou 311121, China)

Abstract

Bipolar disorder (BD), one of six major mental disorders in China, manifests as recurrent episodes of (hypo)mania and major depression. Recently, researchers have increasingly focused on the cognitive and behavioral characteristics of BD patients. Notably, increased risk-taking might emerge as a typical symptom of BD, supported by evidence from BD patients' daily behaviors, empirical research, and neuroimaging studies. However, contradictory findings have been reported, with some studies failing to find differences in risk preferences between BD patients and healthy controls (HCs) and a few studies even indicating increased risk aversion among BD patients. Consequently, whether and to what extent BD is associated with alterations in risk preference remain unclear. Thus, this study involved a three-level meta-analysis to examine the relationship between BD and risky decision-making, encompassing studies utilizing various measures of risky decision-making (i.e., risk attitude scales, behavioral tasks, and daily risk behaviors). Moreover, we aimed to uncover potential moderators, including sample and measurement characteristics, to better address inconsistent findings.

A systematic literature search"was conducted with the Web of Science, PubMed, Scopus, PsycINFO, CNKI (China National Knowledge Infrastructure), and WFD (Wan Fang Data) databases up to April 15, 2024, to identify studies investigating risky decision-making in BD patients and HCs. We calculated the standard mean differences (Hedges' g) in risky decision-making between BD patients and HCs. We conducted a three-level random-effects meta-analysis, including heterogeneity analysis, moderation analyses for sample and measurement characteristics, and assessments of publication bias.

Across 176 effect sizes in 71 cross-sectional studies, BD patients exhibited greater risk-seeking than HCs (Hedges' g"= 0.301), regardless of whether it was measured via risk attitude scales (Hedges' g"= 0.624), behavioral tasks (Hedges' g"= 0.252) or daily risk behaviors (Hedges' g"= 0.312). Moreover, this difference was also moderated by age (β"= 0.009) and mood phase, where BD patients in any mood phase preferred more risk-seeking than HCs (euthymic: Hedges' g"= 0.245; (hypo)mania: Hedges' g"= 0.604; major depression: Hedges' g"= 0.417). For behavioral tasks, age (β = 0.012) and region were found to have significant moderating effects. Specifically, significant effect sizes were observed for samples originating from Europe (Hedges' g"= 0.419) and South America (Hedges' g"= 0.420). Moreover, effect sizes were significant in studies using the Iowa Gambling Task (IGT; Hedges' g"= 0.396) and Cambridge Gambling Task (Hedges' g = 0.220), and effect sizes in IGT studies were larger than in those employing the Classic Risky Choice Tasks. Regarding. With respect to daily attitudes/behaviors, mood phase was identified as a significant moderator. Notably, effect sizes for (hypo)manic patients (Hedges' g"= 0.747) were significantly larger than those for euthymic patients. Moreover, compared with HCs, BD patients exhibited increased risk-seeking across the health (Hedges' g"= 0.308), financial (Hedges' g"= 0.331), and overall attitude (Hedges' g"= 0.733) domains.

This study comprehensively explored the relationship between BD and risky decision-making via various measures, revealing a consistent pattern of increased risk-seeking among BD patients. These findings suggest that increased risk-taking might be a noteworthy symptom of BD and propose potential utility for its application in clinical management and psychoeducation. Furthermore, future studies should consider factors such as mood phase and task type and try to uncover the underlying psychological mechanisms through which BD affects risky decision-making.

Keywords "Bipolar disorder, risky decision-making, meta-analysis, decision task, cross-mood specificity

附錄新增參考文獻

Bechara, A., Damasio, A. R., Damasio, H., amp; Anderson, S. W. (1994). Insensitivity to future consequences following damage to human prefrontal cortex. Cognition, 50(1-3), 7–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0277(94)90018-3

Rogers, R. D., Everitt, B. J., Baldacchino, A., Blackshaw, A. J., Swainson, R., Wynne, K., ... Robbins, T. W. (1999). Dissociable deficits in the decision-making cognition of chronic amphetamine abusers, opiate abusers, patients with focal damage to prefrontal cortex, and tryptophan-depleted normal volunteers: evidence for monoaminergic mechanisms."Neuropsychopharmacology, 20(4), 322–339. https://doi."org/10.1016/S0893-133X (98)00091-8