語言之死

By+Rebecca+Roache

任何東西的逝去和消亡都會讓人感傷,語言也不例外。對于那些母語是瀕危語言的人來說,語言的消亡使他們承受著巨大的痛苦和不公。但對于其他人來說,保護少數民族語言似乎并沒有那么大的意義。我們應該如何看待這種矛盾?我們又該怎樣理解語言消亡所帶來的感傷?

The year 2010 saw the death of Boa Senior, the last living speaker of Aka-Bo, a tribal language native to the Andaman Islands in the Bay of Bengal. Tales of language extinction are invariably tragic. But why, exactly? Aka-Bo, like many other extinct languages, did not make a difference to the lives of the vast majority of people. Yet the sense that we lose something valuable when languages die is familiar. Just as familiar, though, is the view that preserving minority languages is a waste of time and resources. I want to attempt to make sense of these conflicting attitudes.

The simplest definition of a minority language is one that is spoken by less than half of some country or region. This makes Mandarin—the worlds most widely spoken language—a minority language in many countries. Usually, when we talk of minority languages,we mean languages that are minority languages even in the country in which they are most widely spoken. That will be our focus here. Were concerned especially with minority languages that are endangered, or that would be endangered were it not for active efforts to support them.

The sorrow we feel about the death of a language is complicated. Boa Seniors demise1 did not merely mark the extinction of a language. It also marked the loss of the culture of which she was once part. There is, in addition, something melancholy2 about the very idea of a languages last speaker; of a person who suffered the loss of everyone to whom he was once able to chat in his mother tongue.

Part of our sadness when a language dies has nothing to do with the language itself. Thriving majority languages do not come with tragic stories, and so they do not arouse our emotions in the same ways. Unsurprisingly, concern for minority languages is often dismissed as3 sentimental. Researchers on language policy have observed that majority languages tend to be valued for being useful and for facilitating4 progress, while minority languages are seen as barriers to progress, and the value placed on them is seen as mainly sentimental.

Sentimentality, we tend to think, is an exaggerated emotional attachment to something. It is exaggerated because it does not reflect the value of its object. We all treasure such things—a decades-old rubber, our childrens drawings, a long-expired train ticket from a trip to see the one we love—that are worthless to other people. The same might be true of minority languages: their value to some just doesnt warrant5 the society-wide effort required to preserve them.endprint

There are a couple of responses to this. First, the value of minority languages is not purely sentimental. Languages are scientifically interesting. There are whole fields of study devoted to them—to charting their history, relationships to other languages, relationships to the cultures in which they exist, and so on. Understanding languages even helps us to understand the way we think. Some believe that the language we speak influences the thoughts we have, or even that language is what makes thought possible.

Second, lets take a closer look at sentimental value. Why do we call some ways of valuing “sentimental”? We often do this when someone values something to which they have a particular personal connection. Things that have personal value are valued much less by people who do not have the right sort of personal connection to them. This sort of value is behind the thriving market in celebrity autographs, and it is why parents around the world stick their childrens drawings to the fridge.

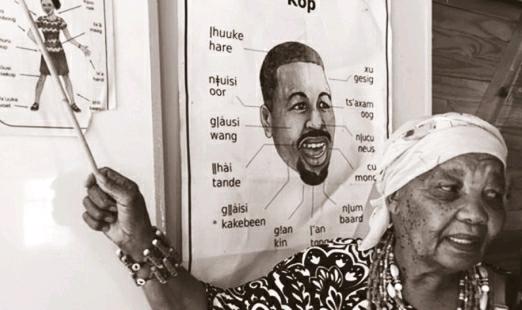

Historical and cultural significance is part of why we value languages. Katrina Esau, aged 84, is one of only three remaining speakers of N|uu, a South African “click”language.6 For the past decade, she has run a school in her home, teaching N|uu to local children in an effort to preserve it.

Even people who are unsympathetic to efforts to support minority languages are, I imagine, less baffled by Esaus desire to preserve N|uu than they would be by a campaign for the creation and proliferation of a completely new artificial language.7 The reason why its better to preserve currently existing natural languages than to create new ones is because of the historical and personal value of the former. These are exactly the sort of values associated with sentimentality.

Minority languages, then, are valuable. Does that mean that societies should invest in supporting them? Not necessarily. The value of minority languages might be outweighed by the value of not supporting them. Therere two reasons: the burden that supporting minority languages places on people, and the benefits of reducing language diversity.

While we might value minority languages for similar reasons that we value medieval castles, there is an important difference in how we can go about preserving the two types of thing. We can preserve a castle by paying people to maintain it. But we cant preserve a minority language by paying people to carry out maintenance. Instead, we must get people to make the language a big part of their lives, which is necessary if they are to become competent speakers. Often this involves legislation to ensure that children learn the minority language at school.endprint

Some parents think that it would be better for their children to learn a useful majority language rather than a less useful minority language. However, for native English speakers, the most commonly taught majority languages—French, German, Spanish, Italian—are not as useful as they first seem. Because English is so widely spoken, even an English-speaking monoglot8 can make himself understood pretty well when visiting these countries. If he decides to invest effort in learning one of these languages, he can expect relatively little return on his investment in terms of usefulness.

In that case, why is it so widely seen as a good thing for English-speaking children to learn majority languages such as French, German and Spanish? I think it is the same reason that many claim its a good thing to learn a minority language: to gain an insight into an unfamiliar culture, to be able to signal respect by speaking to people in the local language, to hone9 the cognitive skills one gains by learning a language, and so on.

Finally, lets consider a very different reason to resist the view that we should support minority languages. Language diversity is a barrier to successful communication. The advantages to adopting a single language are clear. It would enable us to travel anywhere in the world, confident that we could communicate with the people we met. We would save money on translation and interpretation. Scientific advances and other news could be shared faster and more thoroughly.

It would be difficult, however, to implement a lingua franca peacefully and justly.10 The history of language death is a violent one. It would, then, be difficult to embrace a lingua franca without harming speakers of other languages. Given the injustices that the communities of minority language speakers have suffered in the past, it might be that they are owed compensation, and it seems clear that it should not include wiping out and replacing the local language.

Perhaps, if one were a god creating a world from scratch11, it would be better to give the people in that world one language rather than many. But now that we have a world with a rich diversity of languages, all of which are interwoven with distinct histories and cultures, and many of which have survived ill-treatment and ongoing persecution, yet which continue to be celebrated and defended by their communities and beyond—once we have all these things, there is no going back without sacrificing a great deal of what is important and valuable.12endprint

最后一位會說孟加拉灣安達曼群島的部落語言阿卡波語的人,博阿·西尼爾,于2010年去世。關于語言消亡的消息總是令人悲痛的。但這究竟是為什么呢?和其他已經消失的語言一樣,阿卡波語并沒有對大多數人的生活產生什么影響。但是當某種語言消亡時,我們會覺得是失去了寶貴的東西,這種感覺很常見。而同樣地,我們對于“保護少數民族語言是一種浪費時間和資源的事情”的說法也不陌生。我想試著解讀一下這些矛盾的態度。

如果一種語言的使用人數達不到這個國家或地區總人口的一半,那么這種語言就是少數民族語言——這是對少數民族語言最簡單的一種定義。這使得漢語普通話——這種世界上使用人數最多的語言——在很多國家中變成了少數民族語言。但在通常情況下,我們所說的少數民族語言指的是那些即使在某個國家中是最廣泛使用的語言,但依舊屬于少數民族語言的語言。第二種定義下的少數民族語言是本文的關注點。我們尤其關注那些瀕臨滅絕的,或者是那些若缺乏積極有效的保護措施就會瀕臨滅絕的語言。

一種語言的死亡使我們產生的感傷之情是非常復雜的。博阿·西尼爾的去世不僅僅標志著一種語言的消失,還標志著她曾經所處的文化的消失。此外,一想到某些人是最后一位可以說某種語言的人,以及他承受著失去所有他曾經可以用母語交談的人的痛苦,也會讓人感到惆悵。

我們在某種語言消亡時所產生的傷感其中一部分和語言本身并沒有關系。欣欣向榮的被大多數人所使用的語言并不會走向悲慘的境地,因而它們也就不能以相同的方式激發我們的情感。自然地,對少數民族語言的關心經常被當做過于感性的事而被忽視。語言政策的研究者們發現,一個國家中大多數人所使用的語言常常會因為它有用并且能夠促進社會發展而被重視,但少數民族語言卻被看做進步的障礙,對于它們的關注也常被當做感情用事。

我們往往將“感情用事”視為一種被夸大的對某些事物的情感依戀。之所以說它被夸大,是因為這樣的情感并不能如實反映那個被依戀物的價值。我們都會珍視一些對別人來說并沒有價值的東西—— 一塊幾十年的舊橡皮、自己孩子的涂鴉,或是一張去見戀人時留下的早已過期的火車票根。這樣的情況可能也適用于少數民族語言:這些瀕臨滅絕的語言對于某一部分人的價值,并不能保證我們能得到保護其所需的來自全社會范圍內的支持。

對于這種情況,我們需要闡明幾點。第一,重視少數民族語言并不完全是感情用事。語言是科學而有趣的。對于語言,我們開展了完善而全面的研究——追蹤記錄它們的歷史、研究與其他語言之間的關系,以及它們和母體文化之間的關系等等。理解語言甚至可以幫助我們理解自身思考的方式。一些人認為我們所使用的語言能夠影響我們的思想,有人甚至認為語言還可能產生了思想。

其次,讓我們來更加仔細地看一下感情用事的價值取向。為什么我們會把一些價值判斷的方式叫做“感情用事”呢?我們常常會在有人十分重視跟他們自身有特殊關聯的事物時這么說。而對于并沒有這種特殊關聯的人來說,就不會那么重視這些存在個人價值的事物。正因為存在這樣一種價值取向,名人的親筆簽名才會那么有市場,全世界的父母才會把他們孩子的涂鴉貼到冰箱上。

語言的歷史和文化意義也是我們需要重視語言的原因。卡特瑞納·以素今年84歲,是南非一種含有“搭嘴音”的N|uu方言僅剩的三位使用者之一。在過去的十年間,她在她的家鄉建立了一個學校,通過教當地的孩子說N|uu語來保護這種語言。

我覺得,即便那些對于保護少數民族語言不太關心的人來說,比起以素保護N|uu語的強烈愿望,創造和推行一種全新的人造語言可能會更讓他們感到困惑。保護目前存在的語言之所以比創造新語言更好,是因為前者在歷史層面和個人層面具有價值。這些價值也正是和“感情用事”相關聯的東西。

所以,少數民族語言是有價值的。那這就意味著社會應該大舉投入保護它們嗎?未必。少數民族語言的價值可能不如不保護它們的價值大。原因有兩點:一是保護少數民族語言給人們帶來的壓力,二是減少語言多樣性的好處。

雖然我們珍惜少數民族語言的原因可能和重視中世紀城堡相似,但我們如何保護這兩種東西是有重要區別的。我們可以花錢雇人去保護一座城堡。但是我們不能通過花錢讓人們來保護一個少數民族語言。相反地,我們必須讓語言變成人們生活中非常重要的一部分,這對于讓他們成為合格的語言使用者來說是非常必要的。通常情況下,要實現這一點,需要通過立法來確保孩子們能在學校里學習少數民族語言。

一些父母覺得讓他們的孩子學一門有用的大語種可能會比學一門沒那么有用的少數民族語言要好。然而,對于以英語為母語的人來說,他們學的最多的幾個大語種——法語、德語、西班牙語、意大利語——并沒有他們想象中那么有用。由于英語的使用范圍太廣泛了,即便一個只會說英語的人在上述這些國家旅行時也能和當地人溝通得非常好。如果一個人決定學習上述某一種語言的話,在實用性方面,他的投入并不能期望可以得到什么回報。

既然這樣,為什么人們會普遍認為學一門像法語、德語或西班牙語的大語種對以英語為母語的孩子來說是一件好事呢?我覺得這可能和許多人認為學一門少數民族語言是件好事的原因一樣:收獲一種理解陌生文化的洞察力,讓人可以用當地的語言對別人表示尊敬,以及通過學習一門新的語言來鍛煉認知能力等等。

最后,讓我們來考慮一個與眾不同的用來反對“我們應該保護少數民族語言”的理由。語言多樣性是溝通的障礙。使用同一種語言的好處是顯而易見的。這能夠讓我們到世界各地旅行,自信地與我們在旅途中遇到的人交流。我們也可以節省筆譯和口譯的錢。科學方面的進展和其他的消息能夠被更加迅速而深入地傳播。

但是,以和平公正的方式來推行一門通用語言是很難的。語言消亡的歷史是充滿暴力的。因而,我們很難在不傷害其他語言使用者的情況下推崇通用語言。考慮到少數民族語言使用者在過去所遭受的不公,他們需要得到一種補償,而且很明顯,這樣的補償不應該包括清除和取代當地的語言。

如果上帝現在要從頭開始創造一個世界的話,他給那個世界的人們同一種語言可能比給他們許多語言要好。但既然我們的世界已經有豐富多彩的語言了,并且所有的語言與各自獨特的歷史文化相互交融,其中許多語言還是經歷了不公正對待和持續不斷的迫害后存活下來的,并繼續被少數民族群體及更多人支持和保護著—— 一旦我們有了所有這些東西,在不犧牲大量重要和有價值的東西的情況下,是沒有回頭路可以走的。

1. demise: 死亡。

2. melancholy: // 憂郁的,使人悲傷的。

3. dismiss as: (因認為某事不重要而)不予認真對待。

4. facilitate: 促進,幫助。

5. warrant: 保證,允諾。

6. N|uu: 南非Tuu語系中的一種方言,瀕臨滅絕;click: 搭嘴音,又叫吸氣音、吮吸音、咂嘴音,是發音方式的一種,多見于非洲東部和南部的語言中。

7. baffle: 使困惑,使為難;proliferation:增殖,擴散。

8. monoglot: // 只會一種語言的人。

9. hone: 磨煉,訓練(技藝等)。

10. implement: 實施,執行;lingua franca: (母語不同的人共用的)通用語。

11. from scratch: 從零開始。

12. interweave with: 與……交織,緊密結合;persecution: 迫害;celebrate: 贊美,頌揚。endprint